Ph.D. AC1.H3 5054 R.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Aniplex of America Announces Simulcast Details for the Irregular at Magic High School and MEKAKUCITY ACTORS

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 4, 2014 Aniplex of America Announces Simulcast Details for The irregular at magic high school and MEKAKUCITY ACTORS ©JIN/1st PLACE, Mekakushidan Anime Production Team © 2013 Tsutomu Sato/PUBLISHED BY KADOKAWA CORPORATION ASCII MEDIA WORKS/MAGIC HIGH SCHOOL COMMITTEE Two Highly-Anticipated Titles will be Streaming on the Aniplex Channel, Hulu, Crunchyroll, and DAISUKI SANTA MONICA, CA (April 4, 2014) –Aniplex of America Inc. has announced today the details of the simulcast schedules for two of their highly-anticipated titles scheduled to begin streaming this month. These titles are The irregular at magic high school and MEKAKUCITY ACTORS. Both of these titles will be available to fans on the Aniplex Channel (www.AniplexChannel.com), Hulu (www.Hulu.com), Crunchyroll (www.crunchyroll.com), and DAISUKI (www.Daisuki.net) only a few hours following its original air-time in Japan. The irregular at magic high school will begin its simulcast schedule on April 5th at 11:00 a.m. (PST) This anime adaptation of the popular sci-fi fantasy light novel series by Tsutomu Sato with the same title features a world where magic is no longer a product of mere legends or fantasy. The story revolves around Tastuya Shiba, his younger sister Miyuki, and the other students enrolled at the National Magic University Affiliated First High School where they are training to become Magic Technicians. For more details on The irregular at magic high school, please visit: www.Mahouka.us MEKAKUCITY ACTORS will begin its simulcast schedule on April 12th at 10:30 a.m. (PST). Originally a Vocaloid song series created by JIN, MEKAKUCITY ACTORS features a group of young men and women in an organization they themselves call the “Mekakushi Dan” (Blindfold Organization) which is made up of members all possessing strange powers related to their eyes. -

Supported Sites

# Supported sites - **1tv**: Первый канал - **1up.com** - **20min** - **220.ro** - **22tracks:genre** - **22tracks:track** - **24video** - **3qsdn**: 3Q SDN - **3sat** - **4tube** - **56.com** - **5min** - **6play** - **8tracks** - **91porn** - **9c9media** - **9c9media:stack** - **9gag** - **9now.com.au** - **abc.net.au** - **abc.net.au:iview** - **abcnews** - **abcnews:video** - **abcotvs**: ABC Owned Television Stations - **abcotvs:clips** - **AcademicEarth:Course** - **acast** - **acast:channel** - **AddAnime** - **ADN**: Anime Digital Network - **AdobeTV** - **AdobeTVChannel** - **AdobeTVShow** - **AdobeTVVideo** - **AdultSwim** - **aenetworks**: A+E Networks: A&E, Lifetime, History.com, FYI Network - **afreecatv**: afreecatv.com - **afreecatv:global**: afreecatv.com - **AirMozilla** - **AlJazeera** - **Allocine** - **AlphaPorno** - **AMCNetworks** - **anderetijden**: npo.nl and ntr.nl - **AnimeOnDemand** - **anitube.se** - **Anvato** - **AnySex** - **Aparat** - **AppleConnect** - **AppleDaily**: 臺灣蘋果⽇報 - **appletrailers** - **appletrailers:section** - **archive.org**: archive.org videos - **ARD** - **ARD:mediathek** - **Arkena** - **arte.tv** - **arte.tv:+7** - **arte.tv:cinema** - **arte.tv:concert** - **arte.tv:creative** - **arte.tv:ddc** - **arte.tv:embed** - **arte.tv:future** - **arte.tv:info** - **arte.tv:magazine** - **arte.tv:playlist** - **AtresPlayer** - **ATTTechChannel** - **ATVAt** - **AudiMedia** - **AudioBoom** - **audiomack** - **audiomack:album** - **auroravid**: AuroraVid - **AWAAN** - **awaan:live** - **awaan:season** -

UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Washi, Momo: Nontraditional Pronoun Usage by a Kansai Japanese Vlogger Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4qc633pf Author Tsai, Karen Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Washi, Momo: Nontraditional Pronoun Usage by a Kansai Japanese Vlogger A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Linguistics by Karen Tsai Committee in charge: Professor Matthew Gordon, Chair Professor Mary Bucholtz Professor Argyro Katsika December 2018 The thesis of Karen Tsai is approved. Mary Bucholtz Argyro Katsika Matthew Gordon, Committee Chair December 2018 Washi, Momo: Nontraditional Pronoun Usage by a Kansai Japanese Vlogger Copyright © 2018 by Karen Tsai iii ABSTRACT Washi, Momo: Nontraditional Pronoun Usage by a Kansai Japanese Vlogger by Karen Tsai Previous literature on Japanese first-person singular (1SG) pronouns deals primarily with encoding of social information such as the speaker’s gender, age, and politeness or formality in Standard Japanese speakers. However, this study investigates the nontradi- tional 1SG pronoun usage of Momona, a 21-year-old Kansai Japanese YouTube vlogger. This study also expands the research on variation of 1SG pronoun usage in conversational speech and casual registers, which are underrepresented in the literature. I argue that Momona’s usage of washi, wai, and washa convey her quirky personality and her identity as a young woman from the Kansai region of Japan, and that her use of atashi, watashi, and watakushi challenge traditional interpretations of Standard Japanese pronoun us- age. -

The Problematic Internationalization Strategy of the Japanese Manga

By Ching-Heng Melody Tu Configuring Appropriate Support: The Problematic Internationalization Strategy of the Japanese Manga and Anime Industry Global Markets, Local Creativities Master’s Program at Erasmus University Rotterdam Erasmus University Rotterdam 2019/7/10 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction ............................................................................................. 4 1.1 Purpose .................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Research Question ................................................................................. 7 1.3 Conceptual Framework ........................................................................ 10 1.4 The Research Method .......................................................................... 12 1.5 Research Scope and Limitation of the Study ......................................... 13 1.5.1 Research Scope ............................................................................... 13 1.5.2 Limitations of the Study .................................................................. 14 1.6 Definition of Terms .............................................................................. 15 1.6.1 Manga ............................................................................................. 15 1.6.2 Anime.............................................................................................. 15 1.6.3 Fansub ............................................................................................ 16 1.7 -

Cool Japan Fund Inc

Press Release Cool Japan Fund Inc. Tokyo, October 30, 2014 Investing in the platform for Internet Streaming and e-commerce business for official Japanese anime content Cool Japan Fund today announced the decision to invest 1 billion yen in a project to develop the platform for internet streaming and e-commerce business for official Japanese anime content, established by a consortium including BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. (BANDAI NAMCO), ASATSU-DK INC. (ADK), and Aniplex Inc. (Aniplex). Through this project, Cool Japan Fund aims to increase the number of overseas fans of Japanese anime and to support the expansion and development of the animation industry in overseas markets through distribution of official Japanese anime content and anime-related goods. Anime, a representation of Japanese pop culture, has acquired a great number of fans around the world. However, the lack of licensed content distribution initiative and the prevalence of piracy activities are causing issues with expanding the anime and anime-related industries in overseas markets. For expansion of the anime-related business overseas, BANDAI NAMCO, ADK, and Aniplex have agreed to found a new company called Anime Consortium Japan Inc., which will be integrated with DAISUKI Inc. (See note 1), a company that operates internet streaming and e-commerce business platform for official Japanese anime content. Cool Japan Fund has decided to support the new integrated initiative, and to invest 1 billion yen. The new company will deliver a broad range of new Japanese anime titles in multiple translated languages in the form of “simulcast distribution” (which is the way that distributes programs in Japan and abroad at the same time) as well as content that was already aired in the past. -

Compatible Games List

MAME ARCADE GAMES LIST - 4600+ Non-duplicated ORIGINAL ROM/Code Arcade Games - Game Name (Alphabetic) 88 Games 99: The Last War 1 on 1 Government 10-Yard Fight '85 10-Yard Fight 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally 18 Challenge Pro Golf 18 Holes Pro Golf 1941: Counter Attack 1942 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen 1943: Battle of Midway 1943: Midway Kaisen 1943: The Battle of Midway 1944: The Loop Master 1945 Part-2 1945k III 1991 Spikes 19XX: The War Against Destiny 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 2020 Super Baseball 280-ZZZAP 3 Bags Full 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex 3 On 3 Dunk Madness 3-D Bowling 30 Test 39 in 1 MAME bootleg 3X3 Puzzle 4 En Raya 4 Fun in 1 4-D Warriors 4nin-uchi Mahjong Jantotsu 64th. Street - A Detective Story 7 e Mezzo 7 Ordi 720 Degrees 7jigen no Youseitachi - Mahjong 7 Dimens... 800 Fathoms 9-Ball Shootout 9-Ball Shootout Championship A Question of Sport A. D. 2083 A.B. Cop Aaargh Abscam Abunai Houkago - Mou Matenai Ace Attacker Ace Driver: Racing Evolution Ace Driver: Victory Lap Acrobat Mission Acrobatic Dog-Fight Act Raiser Act-Fancer Cybernetick Hyper Weapon Action 2000 Action Fighter Action Hollywood Aero Fighters Aero Fighters 2 / Sonic Wings 2 Aero Fighters 3 / Sonic Wings 3 Aero Fighters Special Aeroboto MAME ARCADE GAMES LIST - 4600+ Non-duplicated ORIGINAL ROM/Code Arcade Games - Game Name (Alphabetic) Aerolitos After Burner After Burner II Age Of Heroes - Silkroad 2 Agent Super Bond Agent X Aggressors of Dark Kombat / Tsuukai GANG... Agress - Missile Daisenryaku Ah Eikou no Koshien Air Assault Air Attack Air Buster: Trouble Specialty Raid Unit Air Duel Air Gallet Air Race Air Rescue Airwolf Ajax Akkanbeder Akuma-Jou Dracula Akuu Gallet Aladdin Alcon Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Ali Baba and 40 Thieves Alien Arena Alien Challenge Alien Crush Alien Invaders Alien Invasion Alien Invasion Part II Alien Sector Alien Storm Alien Syndrome Alien vs. -

Owner's Manual

VR-5_e.book 1 ページ 2011年6月10日 金曜日 午後12時47分 Owner's Manual Before using this unit, carefully read the sections entitled: “USING THE UNIT SAFELY”(p. 4) and “IMPORTANT NOTES” (p. 6). These sections provide important information concerning the proper operation of the unit. Additionally, in order to feel assured that you have gained a good grasp of every feature provided by your new unit, owner’s manual should be read in its entirety. The manual should be saved and kept on hand as a convenient reference. Copyright © 2010 ROLAND CORPORATION All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of ROLAND CORPORATION. * Roland is either registered trademark or trademark of Roland Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. * All product names mentioned in this document are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. * The SD logo ( ) and SDHC logo ( ) are trademarks of SD-3C, LLC. VR-5_e.book 2 ページ 2011年6月10日 金曜日 午後12時47分 For the U.K. IMPORTANT: THE WIRES IN THIS MAINS LEAD ARE COLOURED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FOLLOWING CODE. BLUE: NEUTRAL BROWN: LIVE As the colours of the wires in the mains lead of this apparatus may not correspond with the coloured markings identifying the terminals in your plug, proceed as follows: The wire which is coloured BLUE must be connected to the terminal which is marked with the letter N or coloured BLACK. The wire which is coloured BROWN must be connected to the terminal which is marked with the letter L or coloured RED. -

Url 616 Zero(Digi) Npcd

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 616 ZERO(DIGI) NPCD617 CD J-POP-INDIES 1,150 https://tower.jp/item/4061556 44139 テンシトペテンシ BZCD132 Single J-POP-INDIES 695 https://tower.jp/item/4773840 #vs_WORLD w/z. (Produced by Yuto.com) FREO1 CD J-POP-INDIES 1,610 https://tower.jp/item/3937105 #クリティカルヒッターズ これもどうぞ(7"/LTD) BTS2 Analog J-POP-INDIES 850 https://tower.jp/item/4595509 &6allein Part of Me [CD+DVD] MESC0248 Single J-POP-INDIES 1,260 https://tower.jp/item/4812630 (K)NoW_NAME Baby's breath THCS60161 Single J-POP-INDIES 600 https://tower.jp/item/4556166 (K)NoW_NAME Baby's breath (豪華盤) [CD+Blu-ray Disc](BRD) THCS60160 Single J-POP-INDIES 950 https://tower.jp/item/4556164 (K)NoW_NAME Lupinus THCS60159 Single J-POP-INDIES 600 https://tower.jp/item/4556163 (K)NoW_NAME Morning Glory (豪華盤) [CD+Blu-ray Disc] THCS60147 Single J-POP-INDIES 950 https://tower.jp/item/4463722 (K)NoW_NAME Freesia THCS60150 Single J-POP-INDIES 600 https://tower.jp/item/4463725 (K)NoW_NAME Lupinus (豪華盤) [CD+Blu-ray Disc](BRD) THCS60158 Single J-POP-INDIES 950 https://tower.jp/item/4556162 (K)NoW_NAME Morning Glory THCS60148 Single J-POP-INDIES 600 https://tower.jp/item/4463723 (M)otocompo YOKOSHIMA BORDERLINE ep DATN1 Single J-POP-INDIES 695 https://tower.jp/item/4811052 (M)otocompo THE DAY AFTER CHEERING6 Single J-POP-INDIES 232 https://tower.jp/item/3819157 (M)otocompo/Kit Cat POPLOT TIMES 2016 CHRN1010 CD J-POP-INDIES 1,260 https://tower.jp/item/4302092 (plug)INSIDE-OUT eREC-T-Rick CRUE3 CD J-POP-INDIES 715 https://tower.jp/item/3024348 (仮)ALBATRUS Albatrus JSPCDK1008 -

WHETHER You're LOOKING to COMPLETE the FUL SET

COLLECTORS' CORNER! WHETHER You’re lOOKING TO COMPLETE THE FUL SET, COLLECT ALL THE GAMES PUBLISHED IN THE FOUR MAIN TERRITORIES, OR MORE MODESTLY LIST THE TITLES YOU OWN, THE COLLECTor’s CORNER WAS MADE FOR YOU. TITLE PAGE ALTERNATE TITLE RELEASE RELEASE RELEASE DEVELOPER PUBLISHER DATE JP DATE NTSC DATE PAL 2020 SUPER BASEBALL 10 MONOLITH K AMUSEMENT LEASING (JP) / TRADEWEST (US) 3 NINJAS KICK BACK 10 l l MALIBU INTERACTIVE SONY IMAGESOFT 3×3 EYES JÛMA HÔKAN 10 l SYSTEM SUPPLY N-TECH BANPRESTO 3×3 EYES SEIMA KÔRINDEN 10 l NOVA GAMES YUTAKA GREAT BATTLE III (THE) 114 l SUN L BANPRESTO 4-NIN SHÔGI 10 l PLANNING OFFICE WADA PLANNING OFFICE WADA 7TH SAGA (THE) 10 ELNARD (JP) l PRODUCE GAMEPLAN21 (JP) / ENIX AMERICA (US) 90 MINUTES: EUROPEAN PRIME GOAL 11 J.LEAGUE SOCCER PRIME GOAL 3 (JP) l l NAMCO NAMCO (JP) / OCEAN (EU) A.S.P AIR STRIKE PATROL 11 DESERT FIGHTER (EU) l l OPUS SETA (JP-US) / SYSTEM 3 (EU) AAAHH!!! REAL MONSTERS 12 l l l REALTIME ASSOCIATES VIACOM NEW MEDIA ABC MONDAY NIGHT FOOTBALL 11 l l KÛSÔ KAGAKU DATA EAST ACCELE BRID 11 l Gl ENKI TOMY ACE O NERAE! 11 l TELENET JAPAN TELENET JAPAN ACME ANIMATION FACTORY 12 l PROBE SOFTWARE SUNSOFT ACROBAT MISSION 12 l l MICRONICS TECHIKU ACTION PACHIO 12 l C-LAB COCONUTS JAPAN ACTRAISER 13 l QUINTET ENIX (JP-EU) / ENIX AMERICA (US) ACTRAISER 2 14 ACTRAISER 2: CHINMOKU E NO SEISEN (JP) l l l QUINTET ENIX (JP) / ENIX AMERICA (US) / UBISOFT (EU) ADDAMS FAMILY (THE) 14 l l l OCEAN MISAWA (JP) / OCEAN (EU-US) ADDAMS FAMILY (THE): PUGSley’S SCAVENGER HUNT 14 l l l OCEAN OCEAN ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES 14 l l OCEAN OCEAN ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS: EYE OF THE BEHOLDER 15 l Cl APCOM CAPCOM ADVENTURES OF BATMAN & ROBIN (THE) 15 l l KONAMI KONAMI ADVENTURES OF DR. -

TGS2020 ONLINE Reveals 402 Exhibitors and Live Streaming

The Future Touches Gaming First. Press Release September 8, 2020 TGS2020 ONLINE Update TGS2020 ONLINE Reveals 402 Exhibitors and Live Streaming Schedule Official English Website Launched Today and Special Amazon Venue to be Soft Launched Main Visual and e-Sports X Competition Titles Unveiled Computer Entertainment Supplier’s Association Computer Entertainment Supplier’s Association (CESA, Chairman: Hideki Hayakawa) announced the latest updates on exhibitors and official exhibitor programs currently planned as of September 1 on the official website of TOKYO GAME SHOW 2020 ONLINE (TGS2020 ONLINE: https://tgs.cesa.or.jp/) which will be held from September 23 (Wed.) to 27 (Sun.), 2020. As of September 1, a total of 402 companies and groups, 204 from Japan and 198 from overseas, are registered as exhibitors for TGS2020 ONLINE. Each exhibitor’s profile, game titles and services to be showcased and information to be revealed during the exhibition period are now updated on the “Exhibitors List” page and the “Exhibitor Profile” page of the official TGS2020 ONLINE website. Available on various platforms including home game consoles, PC and smartphones, the website will deliver latest news in a variety of gaming genres, including popular new releases, titles chosen for eSports competitions, and state-of-the-art VR (virtual reality) games. The streaming of Official Exhibitor Programs, one of the highlights for TGS2020 ONLINE, will be participated by a total of 34 companies (29 from Japan, 5 from overseas), and 36 programs will be streamed on live from September 24 to 27. The names of participating exhibitors and streaming schedule are announced today, with the program titles and outlines being as of September 1. -

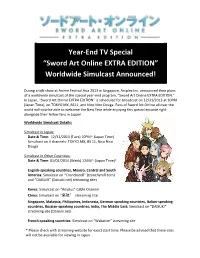

Sword Art Online EXTRA EDITION” Worldwide Simulcast Announced!

Year-End TV Special “Sword Art Online EXTRA EDITION” Worldwide Simulcast Announced! During a talk show at Anime Festival Asia 2013 in Singapore, Aniplex Inc. announced their plans of a worldwide simulcast of the special year-end program, “Sword Art Online EXTRA EDITION.” In Japan, “Sword Art Online EXTRA EDITION” is scheduled for broadcast on 12/31/2013 at 10PM (Japan Time), on TOKYO MX, BS11, and Nico Nico Douga. Fans of Sword Art Online all over the world will now be able to welcome the New Year while enjoying this special episode right alongside their fellow fans in Japan! Worldwide Simulcast Details: Simulcast in Japan: Date & Time: 12/31/2013 (Tues) 10PM~ (Japan Time) Simulcast on 3 channels- TOKYO MX, BS 11, Nico Nico Douga Simulcast in Other Countries: Date & Time: 01/01/2014 (Weds) 12AM~ (Japan Time)* English-speaking countries, Mexico, Central and South America: Simulcast on “Crunchyroll” (crunchyroll.com) and “DAISUKI” (Daisuki.net) streaming sites Korea: Simulcast on “Aniplus” Cable Channel China: Simulcast on “楽視” streaming site Singapore, Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, German-speaking countries, Italian-speaking countries, Russian-speaking countries, India, The Middle East: Simulcast on “DAISUKI” streaming site (Daisuki.net) French-speaking countries: Simulcast on “Wakanim” streaming site * Please check with streaming website for exact start time. Please be advised that these sites will not be available for viewing in Japan. About Sword Art Online EXTRA EDITION Kirito and the others decide to go on an underwater quest within the world of ALO to grant Yui her wish to see a whale. As they all prepare for the quest, they face a shocking revelation… Leafa, or Suguha is afraid of water.