Baryogenesis in the Desert Between Electroweak and Grand Unification Scale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 17 : the Cosmic Microwave Background

Let’s think about the early Universe… Lecture 17 : The Cosmic ! From Hubble’s observations, we know the Universe is Microwave Background expanding ! This can be understood theoretically in terms of solutions of GR equations !Discovery of the Cosmic Microwave ! Earlier in time, all the matter must have been Background (ch 14) squeezed more tightly together ! If crushed together at high enough density, the galaxies, stars, etc could not exist as we see them now -- everything must have been different! !The Hot Big Bang This week: read Chapter 12/14 in textbook 4/15/14 1 4/15/14 3 Let’s think about the early Universe… Let’s think about the early Universe… ! From Hubble’s observations, we know the Universe is ! From Hubble’s observations, we know the Universe is expanding expanding ! This can be understood theoretically in terms of solutions of ! This can be understood theoretically in terms of solutions of GR equations GR equations ! Earlier in time, all the matter must have been squeezed more tightly together ! If crushed together at high enough density, the galaxies, stars, etc could not exist as we see them now -- everything must have been different! ! What was the Universe like long, long ago? ! What were the original contents? ! What were the early conditions like? ! What physical processes occurred under those conditions? ! How did changes over time result in the contents and structure we see today? 4/15/14 2 4/15/14 4 The Poetic Version ! In a brilliant flash about fourteen billion years ago, time and matter were born in a single instant of creation. -

Baryogenesis and Dark Matter from B Mesons: B-Mesogenesis

Baryogenesis and Dark Matter from B Mesons: B-Mesogenesis Miguel Escudero Abenza [email protected] arXiv:1810.00880, PRD 99, 035031 (2019) with: Gilly Elor & Ann Nelson Based on: arXiv:2101.XXXXX with: Gonzalo Alonso-Álvarez & Gilly Elor New Trends in Dark Matter 09-12-2020 The Universe Baryonic Matter 5% 26% Dark Matter 69% Dark Energy Planck 2018 1807.06209 Miguel Escudero (TUM) B-Mesogenesis New Trends in DM 09-12-20 !2 Theoretical Understanding? Motivating Question: What fraction of the Energy Density of the Universe comes from Physics Beyond the Standard Model? 99.85%! Miguel Escudero (TUM) B-Mesogenesis New Trends in DM 09-12-20 !3 SM Prediction: Neutrinos 40% 60% Photons Miguel Escudero (TUM) B-Mesogenesis New Trends in DM 09-12-20 !4 The Universe Baryonic Matter 5% 26% Dark Matter 69% Dark Energy Planck 2018 1807.06209 Miguel Escudero (TUM) B-Mesogenesis New Trends in DM 09-12-20 !5 Baryogenesis and Dark Matter from B Mesons: B-Mesogenesis arXiv:1810.00880 Elor, Escudero & Nelson 1) Baryogenesis and Dark Matter are linked 2) Baryon asymmetry directly related to B-Meson observables 3) Leads to unique collider signatures 4) Fully testable at current collider experiments Miguel Escudero (TUM) B-Mesogenesis New Trends in DM 09-12-20 !6 Outline 1) B-Mesogenesis 1) C/CP violation 2) Out of equilibrium 3) Baryon number violation? 2) A Minimal Model & Cosmology 3) Implications for Collider Experiments 4) Dark Matter Phenomenology 5) Summary and Outlook Miguel Escudero (TUM) B-Mesogenesis New Trends in DM 09-12-20 !7 Baryogenesis -

The Matter – Antimatter Asymmetry of the Universe and Baryogenesis

The matter – antimatter asymmetry of the universe and baryogenesis Andrew Long Lecture for KICP Cosmology Class Feb 16, 2017 Baryogenesis Reviews in General • Kolb & Wolfram’s Baryon Number Genera.on in the Early Universe (1979) • Rio5o's Theories of Baryogenesis [hep-ph/9807454]} (emphasis on GUT-BG and EW-BG) • Rio5o & Trodden's Recent Progress in Baryogenesis [hep-ph/9901362] (touches on EWBG, GUTBG, and ADBG) • Dine & Kusenko The Origin of the Ma?er-An.ma?er Asymmetry [hep-ph/ 0303065] (emphasis on Affleck-Dine BG) • Cline's Baryogenesis [hep-ph/0609145] (emphasis on EW-BG; cartoons!) Leptogenesis Reviews • Buchmuller, Di Bari, & Plumacher’s Leptogenesis for PeDestrians, [hep-ph/ 0401240] • Buchmulcer, Peccei, & Yanagida's Leptogenesis as the Origin of Ma?er, [hep-ph/ 0502169] Electroweak Baryogenesis Reviews • Cohen, Kaplan, & Nelson's Progress in Electroweak Baryogenesis, [hep-ph/ 9302210] • Trodden's Electroweak Baryogenesis, [hep-ph/9803479] • Petropoulos's Baryogenesis at the Electroweak Phase Transi.on, [hep-ph/ 0304275] • Morrissey & Ramsey-Musolf Electroweak Baryogenesis, [hep-ph/1206.2942] • Konstandin's Quantum Transport anD Electroweak Baryogenesis, [hep-ph/ 1302.6713] Constituents of the Universe formaon of large scale structure (galaxy clusters) stars, planets, dust, people late ame accelerated expansion Image stolen from the Planck website What does “ordinary matter” refer to? Let’s break it down to elementary particles & compare number densities … electron equal, universe is neutral proton x10 billion 3⇣(3) 3 3 n =3 T 168 cm− neutron x7 ⌫ ⇥ 4⇡2 ⌫ ' matter neutrinos photon positron =0 2⇣(3) 3 3 n = T 413 cm− γ ⇡2 CMB ' anti-proton =0 3⇣(3) 3 3 anti-neutron =0 n =3 T 168 cm− ⌫¯ ⇥ 4⇡2 ⌫ ' anti-neutrinos antimatter What is antimatter? First predicted by Dirac (1928). -

Baryogenesis and Dark Matter from B Mesons

Baryogenesis and Dark Matter from B mesons Abstract: In [1] a new mechanism to simultaneously generate the baryon asymmetry of the Universe and the Dark Matter abundance has been proposed. The Standard Model of particle physics succeeds to describe many physical processes and it has been tested to a great accuracy. However, it fails to provide a Dark Matter candidate, a so far undetected component of matter which makes up roughly 25% of the energy budget of the Universe. Furthermore, the question arises why there is a more matter (or baryons) than antimatter in the Universe taking into account that cosmology predicts a Universe with equal parts matter and anti-matter. The mechanism to generate a primordial matter-antimatter asymmetry is called baryogenesis. Any successful mechanism for baryogenesis needs to satisfy the three Sakharov conditions [2]: • violation of charge symmetry and of the combination of charge and parity symmetry • violation of baryon number • departure from thermal equilibrium In this paper [1] a new mechanism for the generation of a baryon asymmetry together with Dark Matter production has been proposed. The mechanism proposed to explain the observed baryon asymetry as well as the pro- duction of dark matter is developed around a fundamental ingredient: a new scalar particle Φ. The Φ particle is massive and would dominate the energy density of the Universe after inflation but prior to the Bing Bang nucleosynthesis. The same particle will directly decay, out of thermal equilibrium, to b=¯b quarks and if the Universe is cool enough ∼ O(10 MeV), the produced b quarks can hadronize and form B-mesons. -

Origin and Evolution of the Universe Baryogenesis

Physics 224 Spring 2008 Origin and Evolution of the Universe Baryogenesis Lecture 18 - Monday Mar 17 Joel Primack University of California, Santa Cruz Post-Inflation Baryogenesis: generation of excess of baryon (and lepton) number compared to anti-baryon (and anti-lepton) number. in order to create the observed baryon number today it is only necessary to create an excess of about 1 quark and lepton for every ~109 quarks+antiquarks and leptons +antileptons. Other things that might happen Post-Inflation: Breaking of Pecci-Quinn symmetry so that the observable universe is composed of many PQ domains. Formation of cosmic topological defects if their amplitude is small enough not to violate cosmological bounds. There is good evidence that there are no large regions of antimatter (Cohen, De Rujula, and Glashow, 1998). It was Andrei Sakharov (1967) who first suggested that the baryon density might not represent some sort of initial condition, but might be understandable in terms of microphysical laws. He listed three ingredients to such an understanding: 1. Baryon number violation must occur in the fundamental laws. At very early times, if baryon number violating interactions were in equilibrium, then the universe can be said to have “started” with zero baryon number. Starting with zero baryon number, baryon number violating interactions are obviously necessary if the universe is to end up with a non-zero asymmetry. As we will see, apart from the philosophical appeal of these ideas, the success of inflationary theory suggests that, shortly after the big bang, the baryon number was essentially zero. 2. CP-violation: If CP (the product of charge conjugation and parity) is conserved, every reaction which produces a particle will be accompanied by a reaction which produces its antiparticle at precisely the same rate, so no baryon number can be generated. -

Kinetics of Spontaneous Baryogenesis

Kinetics of Spontaneous Baryogenesis Elena Arbuzova Dubna University & Novosibirsk State University based on common work with A.D. Dolgov and V.A. Novikov arXiv:1607.01247 The 10th APCTP-BLTP/JINR-RCNP-RIKEN Joint Workshop on Nuclear and Hadronic Physics Aug. 17 - Aug. 21, 2016, RIKEN, Wako, Japan E. Arbuzova () Kinetics of SBG August 18 1 / 30 Outline Introduction Generalities about SBG Evolution of Baryon Asymmetry Kinetic Equation in Time-dependent Background Conclusions E. Arbuzova () Kinetics of SBG August 18 2 / 30 Standard Cosmological Model (SCM) The Standard Model of Cosmology: the Standard Model of particle physics ) matter content General Relativity ) gravitational interaction the inflationary paradigm ) to fix a few problems of the scenario SCM explains a huge amount of observational data: Hubble's law the primordial abundance of light elements the cosmic microwave background E. Arbuzova () Kinetics of SBG August 18 3 / 30 Some Puzzles Matter Inventory of the Universe: Baryonic matter (mainly protons and neutrons): 5%. Dark matter (weakly interactive particles not belonging to the MSM of particle physics): 25%. Dark energy: 70% of the Universe is really a mystery looking like a uniformly distributed substance with an unusual equation of state P ≈ −%. DE is responsible for the contemporary accelerated expansion of the Universe. The mechanism of inflation still remains at the level of paradigm. It does not fit the framework of the Standard Model of particle physics. Matter-antimatter asymmetry around us: the local Universe is clearly -

Lesson 8 : Baryogenesis

Lesson 8 : Baryogenesis Notes from Prof. Susskind video lectures publicly available on YouTube 1 Introduction Baryogenesis means the creation of matter particles. Its study is more specifically concerned with explaining the excess of matter over antimatter in the universe. The conditions which explain the imbalance of particles and antiparticles are called nowadays the Sakharov conditions 1. In the previous chapter, we studied several landmarks in the temperature of the universe. Going backwads in time, we met the decoupling time when the universe become trans- parent. The temperature was about 4000°. Further back at T ≈ 1010 degrees, photons could create electron-positron pairs. Protons had already been created earlier. Even further back at T ≈ 1012 or 1013, photons could create proton-antiproton pairs. More accurately they could create quark-antiquark pairs, because in truth it was too hot for protons to exist as such. But, at that temperature, let’s say by convention that when we talk about a proton we really talk about three quarks. It does not make any difference in the reasonings. 1. Named after Andrei Sakharov (1921 - 1989), Russian nuclear physicist. Sakharov published his work on this in 1967 in Russian and it remained little known until the 1980s. In the meantime, the same conditions were rediscovered in 1980 by Savas Dimopoulos and Leonard Susskind who were trying to answer the question of why the number of photons, which is a measure of the entropy of the universe, exceeds by eight orders of magnitude the number of protons or electrons. Thus for a time the conditions were known in the West as the Dimopoulos-Susskind conditions. -

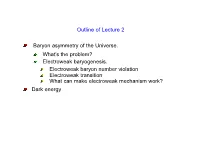

Outline of Lecture 2 Baryon Asymmetry of the Universe. What's

Outline of Lecture 2 Baryon asymmetry of the Universe. What’s the problem? Electroweak baryogenesis. Electroweak baryon number violation Electroweak transition What can make electroweak mechanism work? Dark energy Baryon asymmetry of the Universe There is matter and no antimatter in the present Universe. Baryon-to-photon ratio, almost constant in time: nB 10 ηB = 6 10− ≡ nγ · Baryon-to-entropy, constant in time: n /s = 0.9 10 10 B · − What’s the problem? Early Universe (T > 1012 K = 100 MeV): creation and annihilation of quark-antiquark pairs ⇒ n ,n n q q¯ ≈ γ Hence nq nq¯ 9 − 10− nq + nq¯ ∼ How was this excess generated in the course of the cosmological evolution? Sakharov conditions To generate baryon asymmetry, three necessary conditions should be met at the same cosmological epoch: B-violation C-andCP-violation Thermal inequilibrium NB. Reservation: L-violation with B-conservation at T 100 GeV would do as well = Leptogenesis. & ⇒ Can baryon asymmetry be due to electroweak physics? Baryon number is violated in electroweak interactions. Non-perturbative effect Hint: triangle anomaly in baryonic current Bµ : 2 µ 1 gW µνλρ a a ∂ B = 3colors 3generations ε F F µ 3 · · · 32π2 µν λρ ! "Bq a Fµν: SU(2)W field strength; gW : SU(2)W coupling Likewise, each leptonic current (n = e, µ,τ) g2 ∂ Lµ = W ε µνλρFa Fa µ n 32π2 · µν λρ a 1 Large field fluctuations, Fµν ∝ gW− may have g2 Q d3xdt W ε µνλρFa Fa = 0 ≡ 32 2 · µν λρ ' # π Then B B = d3xdt ∂ Bµ =3Q fin− in µ # Likewise L L =Q n, fin− n, in B is violated, B L is not. -

Baryogenesis and Dark Matter from B Mesons

Baryogenesis and Dark Matter from B Mesons Miguel Escudero Abenza [email protected] Based on arXiv:1810.00880 Phys. Rev. D 99, 035031 (2019) with: Gilly Elor & Ann Nelson BLV19 24-10-2019 DARKHORIZONS The Universe Baryonic Matter 5 % 26 % Dark Matter 69 % Dark Energy Planck 2018 1807.06209 Miguel Escudero (KCL) Baryogenesis and DM from B Mesons BLV19 24-10-19 2 SM Prediction: Neutrinos 40 % 60 % Photons Miguel Escudero (KCL) Baryogenesis and DM from B Mesons BLV19 24-10-19 3 The Universe Baryonic Matter 5 % 26 % Dark Matter 69 % Dark Energy Planck 2018 1807.06209 Miguel Escudero (KCL) Baryogenesis and DM from B Mesons BLV19 24-10-19 4 Baryogenesis and Dark Matter from B Mesons arXiv:1810.00880 Elor, Escudero & Nelson 1) Baryogenesis and Dark Matter are linked Miguel Escudero (KCL) Baryogenesis and DM from B Mesons BLV19 24-10-19 5 Baryogenesis and Dark Matter from B Mesons arXiv:1810.00880 Elor, Escudero & Nelson 1) Baryogenesis and Dark Matter are linked 2) Baryon asymmetry directly related to B-Meson observables Miguel Escudero (KCL) Baryogenesis and DM from B Mesons BLV19 24-10-19 5 Baryogenesis and Dark Matter from B Mesons arXiv:1810.00880 Elor, Escudero & Nelson 1) Baryogenesis and Dark Matter are linked 2) Baryon asymmetry directly related to B-Meson observables 3) Leads to unique collider signatures Miguel Escudero (KCL) Baryogenesis and DM from B Mesons BLV19 24-10-19 5 Baryogenesis and Dark Matter from B Mesons arXiv:1810.00880 Elor, Escudero & Nelson 1) Baryogenesis and Dark Matter are linked 2) Baryon asymmetry directly -

Standard Model & Baryogenesis at 50 Years

Standard Model & Baryogenesis at 50 Years Rocky Kolb The University of Chicago The Standard Model and Baryogenesis at 50 Years 1967 For the universe to evolve from B = 0 to B ¹ 0, requires: 1. Baryon number violation 2. C and CP violation 3. Departure from thermal equilibrium The Standard Model and Baryogenesis at 50 Years 95% of the Mass/Energy of the Universe is Mysterious The Standard Model and Baryogenesis at 50 Years 95% of the Mass/Energy of the Universe is Mysterious Baryon Asymmetry Baryon Asymmetry Baryon Asymmetry The Standard Model and Baryogenesis at 50 Years 99.825% of the Mass/Energy of the Universe is Mysterious The Standard Model and Baryogenesis at 50 Years Ω 2 = 0.02230 ± 0.00014 CMB (Planck 2015): B h Increasing baryon component in baryon-photon fluid: • Reduces sound speed. −1 c 3 ρ c =+1 B S ρ 3 4 γ • Decreases size of sound horizon. η rdc()η = ηη′′ ( ) SS0 • Peaks moves to smaller angular scales (larger k, larger l). = π knrPEAKS S • Baryon loading increases compression peaks, lowers rarefaction peaks. Wayne Hu The Standard Model and Baryogenesis at 50 Years 0.021 ≤ Ω 2 ≤0.024 BBN (PDG 2016): B h Increasing baryon component in baryon-photon fluid: • Increases baryon-to-photon ratio η. • In NSE abundance of species proportional to η A−1. • D, 3He, 3H build up slightly earlier leading to more 4He. • Amount of D, 3He, 3H left unburnt decreases. Discrepancy is fake news The Standard Model and Baryogenesis at 50 Years = (0.861 ± 0.005) × 10 −10 Baryon Asymmetry: nB/s • Why is there an asymmetry between matter and antimatter? o Initial (anthropic?) conditions: . -

![Arxiv:1411.3398V1 [Hep-Ph] 12 Nov 2014](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8796/arxiv-1411-3398v1-hep-ph-12-nov-2014-2148796.webp)

Arxiv:1411.3398V1 [Hep-Ph] 12 Nov 2014

Baryogenesis A small review of the big picture Csaba Bal´azs, ARC Centre of Excellence for Particle Physics at the Tera-scale School of Physics, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria 3800, Australia I schematically, and very lightly, review some ideas that fuel model building in the field of baryogenesis. Due to limitations of space, and my expertise, this review is incomplete and biased toward particle physics, especially supersymmetry. To appear in the proceedings of the Interplay between Particle and Astroparticle Physics workshop, 18 { 22 August, 2014, held at Queen Mary University of London, UK. 1 Introduction From the point of view of contemporary physics, the Universe is a strange place because it contains a considerable amount of matter. We are so used to the existence of matter around, or for that matter inside, us that we take it for granted. We are, however, hard pressed to explain based on known fundamental principles why the Universe contains mostly matter but hardly any antimatter. Our cardinal principles of the corpuscular world are encapsulated in the Standard Model (SM) of elementary particles. This model contains twelve types of matter particles: six quarks and six leptons. These matter particles are differentiated by two quantum numbers: quarks carry a baryon number and leptons a unit of lepton number. They all have antimatter partners. The mass, and all other quantum numbers, of the anti-particles are the same as their partners', with the exception of electric charge, which is opposite. Baryogenesis models attempt to understand the mechanism through which the cosmic matter-antimatter asymmetry arises in the framework of elementary particle physics. -

Cosmic Microwave Background Anisotropies and Theories Of

Cosmic Microwave Background Anisotropies and Theories of the Early Universe A dissertation submitted in satisfaction of the final requirement for the degree of Doctor Philosophiae SISSA – International School for Advanced Studies Astrophysics Sector arXiv:astro-ph/9512161v1 26 Dec 1995 Candidate: Supervisor: Alejandro Gangui Dennis W. Sciama October 1995 TO DENISE Abstract In this thesis I present recent work aimed at showing how currently competing theories of the early universe leave their imprint on the temperature anisotropies of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation. After some preliminaries, where we review the current status of the field, we con- sider the three–point correlation function of the temperature anisotropies, as well as the inherent theoretical uncertainties associated with it, for which we derive explicit analytic formulae. These tools are of general validity and we apply them in the study of possible non–Gaussian features that may arise on large angular scales in the framework of both inflationary and topological defects models. In the case where we consider possible deviations of the CMB from Gaussian statis- tics within inflation, we develop a perturbative analysis for the study of spatial corre- lations in the inflaton field in the context of the stochastic approach to inflation. We also include an analysis of a particular geometry of the CMB three–point func- tion (the so–called ‘collapsed’ three–point function) in the case of post–recombination integrated effects, which arises generically whenever the mildly non–linear growth of perturbations is taken into account. We also devote a part of the thesis to the study of recently proposed analytic models for topological defects, and implement them in the analysis of both the CMB excess kurtosis (in the case of cosmic strings) and the CMB collapsed three–point function and skewness (in the case of textures).