The Jesuit College Ballets: What We Know and What’S Next

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Dancer Taking Leap Into World of Professional Ballet Vancouver Native Eyeing the Crown at International Contest

Young dancer taking leap into world of professional ballet Vancouver native eyeing the crown at international contest Vancouver native Derek Drilon, currently between gigs with the Joffrey and Boston Ballet companies, will dance with his home school, Northwest Classical Ballet, on June 18. (Courtesy of Northwest Classical Ballet) By Scott Hewitt, Columbian Arts & Features Reporter Published: June 10, 2016, 6:04 AM It’s good to be the prince. “I like playing princely roles. It feels pretty natural to me,” said Derek Drilon, 19. That makes sense. At age 19, the Vancouver native recently assumed a position of young royalty in the largest international dance competition in the world. The Youth America Grand Prix draws thousands of aspiring ballet dancers to regional semi- final competitions in cities all over the world, where professional judges evaluate each dancer’s performance, potential and artistry. Finalists are invited to New York City for the final contest, with prizes of scholarship money to the world’s leading dance academies and the invaluable contacts and connections that follow. Drilon won the semi-final Grand Prix Award in Chicago and was named one of the top six men in the New York finals, for his performance of the Siegfried Variation from “Swan Lake.” In Tchaikovsky’s ballet, Prince Siegfried is enraptured with a woman who has been transformed into a swan — but then falls under the spell of a pretender, with tragic consequences. The prince’s famously expressive solo dance, as he considers his predicament and his passion, require great power and artistry. Comedy is a whole different challenge. -

Notes Upon Dancing Historical and Practical by C. Blasis

: / NOTES UPON DANCING, HISTORICAL AND PRACTICAL, BY C. BLASIS, BALLET MASTER TO THE ROYAL ITALIAN OPERA, COVENT GARDEN ; FINISHING MASTER OF THE IMPERIAL ACADEMY OF DANCING AT MILAN; AUTHOR OF A TREATISE ON DANCING, AND OTHER WORKS ON THEATRICAL ART, PUBLISHED IN ITALY, FRANCE, AND ENGLAND. FOLLOWED BY A HISTORY OF THE IMPERIAL AND ROYAL ACADEMY OF DANCING, AT MILAN, TO WHICH ARE ADDED BIOGRAPHICAL NOTICES OF THE BLASIS FAMILY, INTERSPERSED WITH VARIOUS PASSAGES ON THEATRICAL ART. EDITED AND TRANSLATED, FROM THE ORIGINAL FRENCH AND ITALIAN, by R. BARTON. WITH ENGRAVINGS. ? - 4 . / E r -7 ' • . r ' lionJjon PUBLISHED BY M. DELAPORTE, 116, REGENT STREET, AND SOLD BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. 1847. Digitized by Google M'OOWAN AND CO., GREAT WINDMILL STREET, HAYMAREET Digitized by Google Digitized by Google ; ADVERTISEMENT. (by tiik kditor.) It will be seen, that the principle object of this work is to place that part of the entertainment at the Lyric Theatres or Opera, called the Ballet, on a new basis. This, the eminent artiste, who is the author of this work, has already effected in his own country, where he is patronized and supported by the government, and is there undoubtedly the first in his profession, as he is perhaps in Europe. The true object of the Ballet appears to be the Beautiful in motion, supported by expressive and well-adapted music. This may be effected in two ways, by two classes of movements the one is quick, vehement and joyous, and is no other than Dancing—but the other class of motions is a far different tiling ; it is no less than a mute expression of feelings, passions, ideas, intentions, or any other sensations belonging to a reasonable being—this is properly termed Pantomime, and must also be sus- tained by music, which now becomes a kind of explanatory voice ; and while it greatly assists the Mime, when well adapted to the subject to be ex- pressed by his gestures, it produces upon the mind and feelings of the spectator an extraordinary effect. -

Cal Poly Arts Brings Miami City Ballet to PAC Oct. 5 for Performance of "Coppelia"

California Polytechnic State University Sept. 17, 2004 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: LISA WOSKE (805) 756-7110 Cal Poly Arts Brings Miami City Ballet To PAC Oct. 5 For Performance of "Coppelia" SAN LUIS OBISPO – The light-hearted tale of star-crossed lovers and mistaken identities is exquisitely danced in “Coppelia,” the full-length comic ballet performed by Miami City Ballet on Tuesday, October 5, 2004 at the Christopher Cohan Center. Part of the Cal Poly Arts Great Performances Series, the 19th Century, Romantic era masterpiece of comedy is presented at a special 7 p.m. curtain time. “Coppelia” takes place in three acts and tells the story of two mischievous lovers who, on the eve of their nuptials, find their affection for each other surprisingly put to the test. The beloved classical ballet was first presented by the Paris Opera Ballet on May 2, 1870. The Miami City Ballet production captures the timeless beauty and sweet sensibilities of the classic story. The New Yorker magazine called Miami City Ballet “one of the most daring and rewarding of the younger companies now on the rise.” Founding Miami City Ballet Artistic Director Edward Villella was the first American-born male principal ballet stars of the New York City Ballet (1957-1975). His career is said to have established the male's role in classical dance in the U.S. Villella's vision and style for the Company is based on the neoclassical 20th-century aesthetic established by famed choreographer George Balanchine. The Company’s repertoire features 90 ballets -- including 38 world premieres -- ranging from Balanchine masterworks to pieces by contemporary choreographers such as Paul Taylor. -

Columbus Native Turned Company Dancer Duane Gosa to Perform with Les Ballets Trockadero De Monte Carlo at the Ohio Theatre February 28

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 18, 2017 Columbus Native Turned Company Dancer Duane Gosa to Perform with Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo at the Ohio Theatre February 28 The world’s foremost all-male comic ballet company, Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo was founded in 1974 by a group of ballet enthusiasts for the purpose of presenting a playful, entertaining view of traditional, classical ballet in parody form and “en travesti” (males performing female roles). The Trocks, as they are affectionately known, blend their comic approach with a loving knowledge of dance, proving once and for all that men can, indeed, dance “en pointe” without falling flat on their faces. Columbus native Duane Gosa, a member of the company since 2003, will be performing as Helen Highwaters as well as the Legupski Brothers. CAPA presents Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo at the Ohio Theatre (39 E. State St.) on Tuesday, February 28, at 7:30 pm. Tickets are $20-$40 at the CAPA Ticket Center (39 E. State St.), all Ticketmaster outlets, and www.ticketmaster.com. To purchase tickets by phone, please call (614) 469-0939 or (800) 745-3000. Founded in 1974 by a group of ballet enthusiasts for the purpose of presenting a playful, entertaining view of traditional, classical ballet in parody form and en travesti, Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo first performed in the late-late shows of Off-Off Broadway lofts. The Trocks, as the dancers are affectionately known, quickly garnered a major critical essay by Arlene Croce in The New Yorker which, combined with reviews in The New York Times and The Village Voice, established the company as an artistic and popular success. -

Download Playbill

2021 SALT LAKE CITY SPRING PERFORMANCE FROM CLASSICAL TO CONTEMPORARY, MASTERWORKS THROUGH THE AGES MAY 6–8 ROSE WAGNER PERFORMING ARTS CENTER BALLET WEST ACADEMY STUDENTJONAS MALINKA-THOMPSON | PHOTO BY BEAU PEARSON 2021 SALT LAKE CITY SPRING PERFORMANCE FROM CLASSICAL TO CONTEMPORARY, MASTERWORKS THROUGH THE AGES One of the most unique components of Ballet West Academy is that it provides an opportunity for young dancers to learn and perform roles from classical repertoire as well as new and original works in an atmosphere that replicates a full company experience. Our Spring Performance is a diverse representation of this. PLEASE BE RESPECTFUL, TURN OFF ALL ELECTRONICS. NO PHOTOGRAPHY. UPPER SCHOOL: WESTERN SYMPHONY®, WITH SWAN LAKE SUITE AND OTHER SELECTED PIECES The evening performances (May 6, 7, and 8, 7 pm) are presented by dancers from Levels 5-8, the Professional Training Division, and the Trainee Division of Ballet West Academy. We begin with a historical walk in Denmark, where we see August Bournonville’s A Folk Tale, re-staged after the original by our own Jeff Rogers, former Ballet West principal artist, who has spent countless hours studying the style and works of Bournonville. We are then treated to Swan Lake Suite of Dances, with the invigorating and well- known choreography of Marius Petipa and the powerful music of Tchaikovsky, illuminating for the audience the romantic story of Prince Siegfried and his beloved Swan Princess Odette. Next on the evening’s tour is an original work by award-winning choreographer Francisco Gella. Mr. Gella is world-renowned for his ability to merge styles and inspire today’s emerging dancers. -

Yes, Virginia, Another Ballo Tragico: the National Library of Portugal’S Ballet D’Action Libretti from the First Half of the Nineteenth Century

YES, VIRGINIA, ANOTHER BALLO TRAGICO: THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF PORTUGAL’S BALLET D’ACTION LIBRETTI FROM THE FIRST HALF OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ligia Ravenna Pinheiro, M.F.A., M.A., B.F.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Karen Eliot, Adviser Nena Couch Susan Petry Angelika Gerbes Copyright by Ligia Ravenna Pinheiro 2015 ABSTRACT The Real Theatro de São Carlos de Lisboa employed Italian choreographers from its inauguration in 1793 to the middle of the nineteenth century. Many libretti for the ballets produced for the S. Carlos Theater have survived and are now housed in the National Library of Portugal. This dissertation focuses on the narratives of the libretti in this collection, and their importance as documentation of ballets of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, from the inauguration of the S. Carlos Theater in 1793 to 1850. This period of dance history, which has not received much attention by dance scholars, links the earlier baroque dance era of the eighteenth century with the style of ballet of the 1830s to the 1850s. Portugal had been associated with Italian art and artists since the beginning of the eighteenth century. This artistic relationship continued through the final decades of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century. The majority of the choreographers working in Lisbon were Italian, and the works they created for the S. Carlos Theater followed the Italian style of ballet d’action. -

Ballet's Magic Kingdom

Ballet’s Magic Kingdom Ballet’s Magic Kingdom Selected Writings on Dance in Russia, 1911–1925 Akim Volynsky Translated, Edited, and with an Introduction and Notes by StanleyQ J. Rabinowitz Yale University Press New Haven and London Frontispiece: Yury Annenkov, Akim Volynsky, 1921 (From Yury Annenkov, Portrety [Petrograd: Petropolis, 1922], 41). Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of William McKean Brown. Copyright ∫ 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Portions of this book originally appeared in slightly altered form as ‘‘Against the Grain: Akim Volynskii and the Russian Ballet,’’ Dance Research 14, no. 1 (Summer 1996): 3–41, and ‘‘The House That Petipa Built: Visions and Villains of Akim Volynskii,’’ Dance Research 16, no. 1 (Summer 1998): 26–66, and are reprinted by permission of the journal, the Society for Dance Research, and Edinburgh University Press. Set in Adobe Garamond type by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Volynskii, A. L., 1863–1926. [Selections. English 2008] Ballet’s magic kingdom : selected writings on dance in Russia, 1911–1925 / Akim Volynsky ; translated, edited, and with an introduction and notes by Stanley J. -

The Great Patriotic

MAY 2009 www.passportmagazine.ru The Great Patriotic War In Films and TV Fred Flintstone Pays the Bills Mamo Mia! The alternative universe of the Eurovision Song Contest Travel to: The Kamchatka Peninsular, Mongolia, the Russian North Robert De Niro at Nobu Contents 4 What’s On in Moscow 7 May Holidays 8 Previews Passport selection of May cultural events 8 15 Sport Expat Over 28s Football League 16 Ballet Napoli at the Stansilavsky and Nemirovich- Danchenko Music Theater 20 Cinema Russian War Films 16 The Animation Industry in Trouble 24 Art History Bari-Aizenman Anatoly Bichukov 28 City Beat Izmailovsky Park The History of Kiosks 28 32 Religion St. Catherine’s Church, Moscow 34 Travel Kamchatka Mongolia Kargopolye (The Russian North) 34 42 Restaurant Review Nobu. Opening in Moscow 44 Wine Tasting Four Years of Bordeaux Wines 46 Wine & Dine Listings 48 Out & About 48 50 How To Get a bicycle or scooter in Moscow 52 Columns Legal Column. Daniel Klein Financial Column. Matthew Partridge Real estate Column. Michael Bartley Flintstone tells Wilma where the money has gone 50 May 2009 1 Letter from the Publisher The inclusion of an article about Soviet war fi lms in this month’s Passport is a refl ection of the importance that the Great Patriotic War Expats Are Welcome still plays in Russians’ consciousness. There has been a resurgence in The New English Communication Club interest in war fi lms and TV serials about the Great Patriotic War and viewing ratings have soared. This is hardly surprising given the sheer (NECC) meets twice a week at Cofemax cafe. -

THE SUZANNE FARRELL BALLET Thu, Dec 4, 7:30 Pm Carlson Family Stage

2014 // 15 SEASON Northrop Presents THE SUZANNE FARRELL BALLET Thu, Dec 4, 7:30 pm Carlson Family Stage Swan Lake Allegro Brillante The Concert (Or, The Perils of Everybody) Natalia Magnicaballi and Michael Cook in Balanchine's Swan Lake. Photo © Rosalie O'Connor. Dear Northrop Dance Lovers, Northrop at the University of Minnesota Presents What a wonderful addition to our holiday season in Minnesota–a sparkling ballet sampler with the heart-lifting sounds of live classical music. Tonight’s presentation of The Suzanne Farrell Ballet is one of those “only at Northrop” dance experiences that our audiences clamor for. We’re so happy you are here to be a part of it. Suzanne Farrell is a name recognized and respected the world over as the legendary American ballerina and muse of choreographer George Balanchine. As a dancer, Farrell was SUZANNE FARRELL, Artistic Director in a class all her own and hailed as “the most influential ballerina of the late 20th century.” For most of her career, which spanned three decades, she danced at New York City Ballet, where her artistry inspired Balanchine to create nearly NATALIA MAGNICABALLI HEATHER OGDEN* MICHAEL COOK thirty works especially for her–most of them are masterpieces. ELISABETH HOLOWCHUK Christine Tschida. Photo by Patrick O'Leary, Since retiring from NYCB in 1989, Farrell has dedicated her University of Minnesota. life to preserving and promoting the legacy of her mentor. She has staged Balanchine ballets for many of the world’s VIOLETA ANGELOVA PAOLA HARTLEY leading companies, including St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Ballet (known at the time as Leningrad’s Kirov). -

The Theatrical Career of John E. Owens (1823-1886)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1982 The Theatrical Career of John E. Owens (1823-1886). Thomas Arthur Bogar Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Bogar, Thomas Arthur, "The Theatrical Career of John E. Owens (1823-1886)." (1982). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3791. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3791 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the Film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. -

Performance of the Self in the Theatre of the Elite the King's Theatre, 1760

Performance of the self in the theatre of the elite The King’s Theatre, 1760–1789: The opera house as a political and social nexus for women. Joanna Jarvis A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Birmingham City University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts, Design and Media This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/?ref=chooser-v1 October 2019 Volumes 1 & 2 0 1 Abstract This research takes as its starting point the King’s Theatre in London, known as the Opera House, between 1760 and 1789. It examines the elite women subscribers who were on display and their approach to self-presentation in this social and political nexus. It makes a close examination of four women who sat in the audience at that time, as exemplars of the various experiences and approaches to attending the opera. Recent research has examined the performative offerings at the Opera House, the constitution of the audience and the troubled management of the theatre in that period. What is missing, is an examination of the power of the visual in confirming and maintaining status. As a group the women presented a united front as members of the ruling class, but as individuals they were under observation, as much from their peers as others in the audience and the visual dynamic of this display has not been analysed before. The research uses a combination of methodological approaches from a range of disciplines, including history, psychology and phenomenology, in order to extrapolate a sense of the experience for these women. -

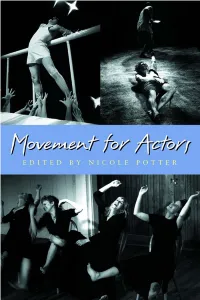

Movement for Actors This Page Intentionally Left Blank Movement for Actors

Movement for Actors This Page Intentionally Left Blank Movement for Actors Edited by NICOLE POTTER © 2002 Nicole Potter The essays in Movement for Actors were written expressly for this book. Copyrights for individual essays are retained by their authors, © 2002. All rights reserved. Copyright under Berne Copyright Convention, Universal Copyright Convention, and Pan-American Copyright Convention. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. 06 05 04 03 02 5 4 3 2 1 Published by Allworth Press An imprint of Allworth Communications, Inc. 10 East 23rd Street, New York, NY 10010 Cover and interior design by Annemarie Redmond Cover photo credits (clockwise, from upper left): Margolis Brown Theater Company, The Bed Experiment, conceived and written by Kari Margolis and Tony Brown, photo: Jim Moore; Theater Ten Ten, King Lear, 1998, directed by Rod McLucas, fight direction by Joe Travers, Jason Hauser (Edmund), Andrew Oswald (Edgar), photo: Sascha Nobés; Shakespeare and Company, Sarah Hickler, Rebecca Perrin, Mary Conway, Susan Dibble, photo: Stephanie Nash. Page composition/typography by Sharp Des!gns, Lansing, MI ISBN: 1-58115-233-7 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Movement for actors / edited by Nicole Potter. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58115-233-7 1. Movement (Acting) I. Potter, Nicole. PN2071.M6 M59 2002 792'.028—dc21