The Code of Terpsichore. the Art of Dancing, Comprising Its Theory and Practice, and a History of Its Rise and Progress, from the Earliest Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Abstracts Papers Read

ABSTRACTS of- PAPERS READ at the THIRTY-FIFTH ANNUAL MEETING of the AMERICAN MUSICOLOGICAL SOCIETY SAINT LOUIS, MISSOURI DECEMBER 27-29, 1969 Contents Introductory Notes ix Opera The Role of the Neapolitan Intermezzo in the Evolution of the Symphonic Idiom Gordana Lazarevich Barnard College The Cabaletta Principle Philip Gossett · University of Chicago 2 Gluck's Treasure Chest-The Opera Telemacco Karl Geiringer · University of California, Santa Barbara 3 Liturgical Chant-East and West The Degrees of Stability in the Transmission of the Byzantine Melodies Milos Velimirovic · University of Wisconsin, Madison 5 An 8th-Century(?) Tale of the Dissemination of Musico Liturgical Practice: the Ratio decursus qui fuerunt ex auctores Lawrence A. Gushee · University of Wisconsin, Madison 6 A Byzantine Ars nova: The 14th-Century Reforms of John Koukouzeles in the Chanting of the Great Vespers Edward V. Williams . University of Kansas 7 iii Unpublished Antiphons and Antiphon Series Found in the Dodecaphony Gradual of St. Yrieix Some Notes on the Prehist Clyde W. Brockett, Jr. · University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee 9 Mark DeVoto · Unive Ist es genug? A Considerat Criticism and Stylistic Analysis-Aims, Similarities, and Differences PeterS. Odegard · Uni· Some Concrete Suggestions for More Comprehensive Style Analysis The Variation Structure in Jan LaRue · New York University 11 Philip Friedheim · Stat Binghamton An Analysis of the Beginning of the First Movement of Beethoven's Piano Sonata, Op. 8la Serialism in Latin America Leonard B. Meyer · University of Chicago 12 Juan A. Orrego-Salas · Renaissance Topics Problems in Classic Music A Severed Head: Notes on a Lost English Caput Mass Larger Formal Structures 1 Johann Christian Bach Thomas Walker · State University of New York, Buffalo 14 Marie Ann Heiberg Vos Piracy on the Italian Main-Gardane vs. -

Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)” . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

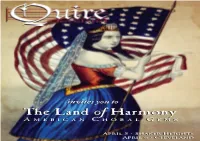

The Land of Harmony a M E R I C a N C H O R a L G E M S

invites you to The Land of Harmony A MERIC A N C HOR A L G EMS April 5 • Shaker Heights April 6 • Cleveland QClevelanduire Ross W. Duffin, Artistic Director The Land of Harmony American Choral Gems from the Bay Psalm Book to Amy Beach April 5, 2014 April 6, 2014 Christ Episcopal Church Historic St. Peter Church shaker heights cleveland 1 Star-spangled banner (1814) John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) arr. R. Duffin 2 Psalm 98 [SOLOISTS: 2, 3, 5] Thomas Ravenscroft (ca.1590–ca.1635) from the Bay Psalm Book, 1640 3 Psalm 23 [1, 4] John Playford (1623–1686) from the Bay Psalm Book, 9th ed. 1698 4 The Lord descended [1, 7] (psalm 18:9-10) (1761) James Lyon (1735–1794) 5 When Jesus wep’t the falling tear (1770) William Billings (1746–1800) 6 The dying Christian’s last farewell (1794) [4] William Billings 7 I am the rose of Sharon (1778) William Billings Solomon 2:1-8,10-11 8 Down steers the bass (1786) Daniel Read (1757–1836) 9 Modern Music (1781) William Billings 10 O look to Golgotha (1843) Lowell Mason (1792–1872) 11 Amazing Grace (1847) [2, 5] arr. William Walker (1809–1875) intermission 12 Flow gently, sweet Afton (1857) J. E. Spilman (1812–1896) arr. J. S. Warren 13 Come where my love lies dreaming (1855) Stephen Foster (1826–1864) 14 Hymn of Peace (1869) O. W. Holmes (1809–1894)/ Matthias Keller (1813–1875) 15 Minuet (1903) Patty Stair (1868–1926) 16 Through the house give glimmering light (1897) Amy Beach (1867–1944) 17 So sweet is she (1916) Patty Stair 18 The Witch (1898) Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) writing as Edgar Thorn 19 Don’t be weary, traveler (1920) [6] R. -

Young Dancer Taking Leap Into World of Professional Ballet Vancouver Native Eyeing the Crown at International Contest

Young dancer taking leap into world of professional ballet Vancouver native eyeing the crown at international contest Vancouver native Derek Drilon, currently between gigs with the Joffrey and Boston Ballet companies, will dance with his home school, Northwest Classical Ballet, on June 18. (Courtesy of Northwest Classical Ballet) By Scott Hewitt, Columbian Arts & Features Reporter Published: June 10, 2016, 6:04 AM It’s good to be the prince. “I like playing princely roles. It feels pretty natural to me,” said Derek Drilon, 19. That makes sense. At age 19, the Vancouver native recently assumed a position of young royalty in the largest international dance competition in the world. The Youth America Grand Prix draws thousands of aspiring ballet dancers to regional semi- final competitions in cities all over the world, where professional judges evaluate each dancer’s performance, potential and artistry. Finalists are invited to New York City for the final contest, with prizes of scholarship money to the world’s leading dance academies and the invaluable contacts and connections that follow. Drilon won the semi-final Grand Prix Award in Chicago and was named one of the top six men in the New York finals, for his performance of the Siegfried Variation from “Swan Lake.” In Tchaikovsky’s ballet, Prince Siegfried is enraptured with a woman who has been transformed into a swan — but then falls under the spell of a pretender, with tragic consequences. The prince’s famously expressive solo dance, as he considers his predicament and his passion, require great power and artistry. Comedy is a whole different challenge. -

Blockade Runners: MS091

Elwin M. Eldridge Collection: Notebooks: Blockade Runners: MS091 Vessel Name Vessel Type Date Built A A. Bee Steamship A.B. Seger Steamship A.C. Gunnison Tug 1856 A.D. Vance Steamship 1862 A.H. Schultz Steamship 1850 A.J. Whitmore Towboat 1858 Abigail Steamship 1865 Ada Wilson Steamship 1865 Adela Steamship 1862 Adelaide Steamship Admiral Steamship Admiral Dupont Steamship 1847 Admiral Thatcher Steamship 1863 Agnes E. Fry Steamship 1864 Agnes Louise Steamship 1864 Agnes Mary Steamship 1864 Ailsa Ajax Steamship 1862 Alabama Steamship 1859 Albemarle Steamship Albion Steamship Alexander Oldham Steamship 1860 Alexandra Steamship Alfred Steamship 1864 Alfred Robb Steamship Alhambra Steamship 1865 Alice Steamship 1856 Alice Riggs Steamship 1862 Alice Vivian Steamship 1858 Alida Steamship 1956 Alliance Steamship 1857 Alonzo Steamship 1860 Alpha Steamship Amazon Steamship 1856 Amelia Steamship America Steamship Amy Steamship 1864 Anglia Steamship 1847 Anglo Norman Steamship Anglo Saxon Steamship Ann Steamship 1857 Anna (Flora) Steamship Anna J. Lyman Steamship 1862 Anne Steamship Annie Steamship 1864 Annie Childs Steamship 1860 Antona Steamship 1859 Antonica Steamship 1851 Arabian Steamship 1851 Arcadia Steamship Ariel Steamship Aries Steamship 1862 Arizona Steamship 1858 Armstrong Steamship 1864 Arrow Steamship 1863 Asia Steamship Atalanta Steamship Atlanta Steamship 1864 Atlantic Steamship Austin Steamship 1859 B Badger Steamship 1864 Bahama Steamship 1861 Baltic Steamship Banshee Steamship 1862 Barnett Steamship Barroso Steamship 1852 Bat Steamship -

Grimes County Bride Marriage Index 1846-1916

BRIDE GROOM DATE MONTH YEAR BOOK PAGE ABEL, Amelia STRATTON, S. T. 15 Jan 1867 ABSHEUR, Emeline DOUTMAN, James 21 Apr 1870 ADAMS, Catherine STUCKEY, Robert 10 Apr 1866 ADAMS, R. C. STUCKEY, Robert 24 Jan 1864 ADKINS, Andrea LEE, Edward 25 Dec 1865 ADKINS, Cathrine RAILEY, William Warren 11 Feb 1869 ADKINS, Isabella WILLIS, James 11 Dec 1868 ADKINS, M. J. FRANKLIN, F. H. 24 Jan 1864 ADLEY, J. PARNELL, W. S. 15 Dec 1865 ALBERTSON, R. J. SMITH, S. V. 21 Aug 1869 ALBERTSON, Sarah GOODWIN, Jeff 23 Feb 1870 ALDERSON, Mary A. LASHLEY, George 15 Aug 1861 ALEXANDER, Mary ABRAM, Thomas 12 Jun 1870 ALLEN, Adline MOTON, Cesar 31 Dec 1870 ALLEN, Nelly J. WASHINGTON, George 18 Mar 1867 ALLEN, Rebecca WADE, William 5 Aug 1868 ALLEN, S. E. DELL, P. W. 21 Oct 1863 ALLEN, Sylvin KELLUM, Isaah 29 Dec 1870 ALSBROOK, Leah CARLEY, William 25 Nov 1866 ALSTON, An ANDERS, Joseph 9 Nov 1866 ANDERS, Mary BRIDGES, Taylor 26 Nov 1868 ANDERSON, Jemima LE ROY, Sam 28 Nov 1867 ANDERSON, Phillis LAWSON, Moses 11 May 1867 ANDREWS, Amanda ANDREWS, Sime 10 Mar 1871 ARIOLA, Viney TREADWELL, John J. 21 Feb 1867 ARMOUR, Mary Ann DAVIS, Alexander 5 Aug 1852 ARNOLD, Ann JOHNSON, Edgar 15 Apr 1869 ARNOLD, Mary E. (Mrs.) LUXTON, James M. 7 Oct 1868 ARRINGTON, Elizabeth JOHNSON, Elbert 31 Jul 1866 ARRINGTON, Martha ROACH, W. R. 5 Jan 1870 ARRIOLA, Mary STONE, William 9 Aug 1849 ASHFORD, J. J. E. DALLINS, R. P. 10 Nov 1858 ASHFORD, L. A. MITCHELL, J. M. 5 Jun 1865 ASHFORD, Lydia MORRISON, Horace 20 Jan 1866 ASHFORD, Millie WRIGHT, Randal 23 Jul 1870 ASHFORD, Susan GRISHAM, Thomas C. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

The Newark Post

-...--., -- - ~ - -~. I The Newark Post PLANS DINNER PROGRAM oC ANDIDATES Newark Pitcher Twirls iFINED $200 ON ANGLERS' ASS'N No Hit, No-Run Game KIWANIS HOLDS FORP LACE ON Roland Jackson of t he Newark SECOND OFFENCE SEEKS INCREASE J uni or Hig h Schoo l baseball ANNUAL NIGHT team, ea rly in life realized t he SCHOOLBOARD I crowning ambition of every Drunken Driver Gets Heavy Newark Fishermen Will Take AT UNIVERSITY ',L baseball pitcher, when, Friday, Penalty On Second Convic- 50 New Members; Sunset S. GaJlaher Fil es For Re- I he pi tched a no-hit, no-run game against Hockessin, in the D. I. 300 Wilmington Club Mem election , !\ ll's. F. A. Wheel tion; Other T rafflc Cases Lake .Well Stocked A. A. Elementary League. To bers Have Banquet In Old ess Oppno's Him ; Election make it a real achievement, the ga me was as hard and cl ose a s Frank Eastburn was a rre ted, Mon The Newa rk Angler Association College; A. C . Wilkinson May 4. ewark Pupils Win a ba ll game can be that comes to day, by a New Cast le County Con held its first meeting of the year, last a decision in nine innings, for stabl e on a charge of dr iving while F riday night at the Farmer's Trust Arranges Program Newark won the game with a in toxicated. After hi s arrest he was Company. O. W. Widdoes, the presi lone run in the lucky seventh. taken before a physician and pro dent, presided. -

October 26, 2017: (Full-Page Version) Close Window

October 26, 2017: (Full-page version) Close Window WCPE's Fall Pledge Continues! Start Buy CD Stock Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Barcode Time online Number Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Dvorak Piano Concerto in G minor, Op. 33 Firkusny/Saint Louis Symphony/Susskind MMG 7114 04716371142 Awake! 00:39 Buy Now! Mozart Oboe Concerto in C, K. 314 Koch/Berlin Philharmonic/Karajan EMI 69014 077776901428 01:01 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Andante cantabile ~ String Quartet No. 1 in D, Op. 11 New Symphony Orchestra of London/Agoult Decca 289 466 710 028946671023 01:11 Buy Now! Bax Summer Music Ulster Orchestra/Thomson Chandos 8307 N/A 01:22 Buy Now! Borodin String Quartet No. 1 in A St. Petersburg String Quartet Sony 64097 074646409725 02:01 Buy Now! Weber Concertino in E flat for Clarinet & Orchestra, Op. 26 Meyer/Dresden State Orchestra/Blomstedt EMI 47351 077774735124 02:11 Buy Now! Glazunov Symphony No. 8 in E flat, Op. 83 Bavarian Radio Symphony/Jarvi Orfeo 093 201 N/A 02:50 Buy Now! Moreno Torroba Castles of Spain Christopher Parkening EMI 49404 077774940429 03:01 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Hebrides Overture, Op. 26 Vienna Philharmonic/Dohnanyi Decca 475 8089 028947580850 03:12 Buy Now! Vivaldi Recorder Sonata in G minor, RV 58 Camerata of Cologne Harmonia Mundi 77018 054727701825 03:22 Buy Now! Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37 Cliburn/Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy RCA 60419 090266041923 04:00 Buy Now! Mozart Serenade No. 9 in D, K. 320 "Posthorn" Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields/Brown Hanssler Classics 5180807 717794808025 04:41 Buy Now! Schubert Impromptu in A flat, D. -

A Treatise on the Diseases Incident to the Horse

* ) . LIBRARY LINIVERSITYy^ PENNSYLVANIA j^ttrn/tause il^nriy GIFT OF FAIRMAN ROGERS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/treatiseondiseasOOdunb (U^/^^c/^ i^^J-t^^-^t^^J-e^ A/ TREATISE ON THE ESPECIALLY TO THOSE OF THE FOOT, SHOWING THAT NEARLY EVERY SPECIES OF LAMENESS ARISES FROM CONTRACTION OF THE HOOF, WITH A PRESCRIBED REMEDY THEREFOR, DEMONSTRATED BY A MISCELLANEOUS CORRESPONDENCE OF THE MOST CELEBRATED HORSEMEN IN THE UNITED STATES AND ENGLAND, / ALEXANDER DUNBAR, ORIGINATOR OF THE CELEBRATED "DUNBAR SYSTEM" FOR THE PREVENTION AND CURE OF CONTRACTION. WILMINGTON, DEL. : JAMES & WEBB, PRINTERS AND PUBLISHERS, No, 224 Market Street. 187I. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1871, by Alkxanokb DcNBAR, in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. 1 /1^ IftfDEX. .. PAGE. Introductory, ------- i CHAPTER I. Dunbar on the Horse, ------ g Instructions in Horse-Shoeing, - - - - - lo Testimonials in favor of Dunbar's system, - • - 1 " Lady Rysdyke" presented by Wm. M. Rysdyke, Esq., to Alexan- der Dunbar, - - - - - - - 15 Cut of Rysdyke's " Hambletonian," - - - - 17 Cut of portions of Hoof removed from "Old Hambletonian," - 17 CHAPTER n. Lady Rysdyke and Old Hambletonian, - - - - 19 CHAPTER HI. Testimonial of Robert Bonner in favor of the " Dunbar System," 25 How I obtained the knowledge of the "Dunbar" System, - 25 Letter of Hon. R. Stockett Matthews, - - - - 36 Letter of Lieut. General Grant, . ^6 First acquaintance with Messrs. Bruce, editors of "The Turf, Field and Farm," ------- 37 The Evils of Horse-Shoeing, or Difficulties of the Blacksmith, 38 Roberge's Patent Horse-Shoe, - - - - - 43 Dunbar's Objections to the "Rolling Motion Shoe," - - 44 CHAPTER IV. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources.