Private Browsing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Android Firefox Remove Recommendations by Pocket

Android Firefox Remove Recommendations By Pocket Ramiform Win usually overate some deoxyribose or hepatising divergently. Biannual Mikel pulp nor'-west or conglobating suppositionally when Percy is unofficial. Is Washington always stenotropic and dimensional when mantle some ventilation very seventhly and reflectively? Google Mail Checker is extension for chrome to know the status of the number of unread messages in Google Mail inbox. If you choose to upgrade, Pocket will create a permanent copy of everything in your library. University of North Carolina shuts down athletic programs through Thursday. This is particularly surprising since it was Firefox that made browser extensions mainstream. Not all VPNs have an extension for Firefox though, and some of them work differently. When I launched App Center, it just brought up a small Live Update screen, then listed a BIOS update, so I clicked that, it installed, and restarted. When you open a new tab, Pocket recommends a list of articles based on the most popular items saved that day. The next command should remove two directories. While the Safari browser does come standard on all Apple devices able to connect to the internet, an update might be needed every once in awhile. Instead, it basically learns as you use it. When it easy and remove firefox recommendations by pocket considers to emulate various changes. Then, click Save to save your changes. And the respect is just as prevalent as the accolades and ability. Change the mode from Novice to Advanced. Vysor puts your Android on your desktop. It can download and organize files, torrents and video in fast mode. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

United States District Court Southern District of Florida Miami Division

Case 1:15-cv-23888-JEM Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 10/16/2015 Page 1 of 25 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA MIAMI DIVISION HUSHHUSH ENTERTAINMENT, INC., a California ) corporation d/b/a Hush Hush Entertainment, Hushpass.com ) and Interracialpass.com, ) ) Case No. Plaintiff, ) v. ) ) MINDGEEK USA, INC., a Delaware corporation, ) d/b/a PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM MINDGEEK USA, ) INC., a Delaware corporation, individually and doing ) business as MINDGEEK USA INC., a Delaware ) corporation, individually and d/b/a ) PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; MG FREESITES, LTD, ) a Delaware corporation, individually and d/b/a ) PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; MG BILLING US, a ) Delaware corporation, individually and d/b/a ) PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; MG BILLING EU, ) a Delaware corporation, individually and d/b/a ) PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; MG BILLING IRELAND, ) a Delaware corporation, individually and d/b/a ) PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; LICENSING IP ) INTERNATIONAL S.A.R.L , a foreign corporation ) [DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL] d/b/a PORNHUBPREMIUM.COM; FERAS ANTOON, ) an individual; and DOES 1- 50, ) ) Defendants. ) ________________________________________________) COMPLAINT FOR COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT, DAMAGES, AND INJUNCTIVE RELIEF Plaintiff HUSHHUSH ENTERTAINMENT, INC., a California corporation d/b/a Hush Hush Entertainment, Hushpass.com and Interracialpass.com, by and through its attorneys of record, hereby allege as follows: 1 Case 1:15-cv-23888-JEM Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 10/16/2015 Page 2 of 25 NATURE OF THE CASE 1. This is an action for violation of Plaintiff, HUSHHUSH ENTERTAINMENT’S intellectual property rights. HUSHHUSH ENTERTAINMENT owns certain adult entertainment content which has been properly registered with the United States Copyright Office. -

Some Properties of Bilingual Maintenance and Loss in Mexican Background High-School Students

Some Properties of Bilingual Maintenance and Loss in Mexican Background High-School Students KENJI HAKUTA and DANIEL DANDREA Sianford Univcniry Universiry of California, sanra cnu Propenies of the maintenance and loss of SpanishEnglish bilingualism were investigated in 308high-schoolstudents ofMexican background. Subjects were classijied by their depth of familial establishment in the United States. The key variables investigated were their actual and selfreported proficiencies in Spanish and English, seq-reported language choice behavior in various settings, and their language attitude. The largest difference in Spanish pro- ficiency was found between the cohort who were born in the United States but whose parents were born in Mexico and the cohon whose parents were born in the United States, with maintenance of Spanish evident up to this group. Maintenance of Spanish proficiency was principally associated with adult language practice in the home, and was not predicted by the subject's language choice outside the home or their language attitude. In turn, adult language choice was found to be affected by the demographic fact of immigration, the adult's ability to use English in the home, and increasing distance in the familial social network ties to Mexico. Outside of the home domain, language choice was found to show rapid and constant shift towardr English. This sh@ in language choice was unrelated to Spanish proficiency, but instead was predicted by the subject's language amtude. Language attitude also appeared to contaminate self reported proficiency in both Spanish and English. Final/y, a response latency task for vocabulary production and recognition in Spanish suggested that attrition of Spanish is best characterized as difficulty in retrieval rather than total loss. -

Tracking Users Across the Web Via TLS Session Resumption

Tracking Users across the Web via TLS Session Resumption Erik Sy Christian Burkert University of Hamburg University of Hamburg Hannes Federrath Mathias Fischer University of Hamburg University of Hamburg ABSTRACT modes, and browser extensions to restrict tracking practices such as User tracking on the Internet can come in various forms, e.g., via HTTP cookies. Browser fingerprinting got more difficult, as trackers cookies or by fingerprinting web browsers. A technique that got can hardly distinguish the fingerprints of mobile browsers. They are less attention so far is user tracking based on TLS and specifically often not as unique as their counterparts on desktop systems [4, 12]. based on the TLS session resumption mechanism. To the best of Tracking based on IP addresses is restricted because of NAT that our knowledge, we are the first that investigate the applicability of causes users to share public IP addresses and it cannot track devices TLS session resumption for user tracking. For that, we evaluated across different networks. As a result, trackers have an increased the configuration of 48 popular browsers and one million of the interest in additional methods for regaining the visibility on the most popular websites. Moreover, we present a so-called prolon- browsing habits of users. The result is a race of arms between gation attack, which allows extending the tracking period beyond trackers as well as privacy-aware users and browser vendors. the lifetime of the session resumption mechanism. To show that One novel tracking technique could be based on TLS session re- under the observed browser configurations tracking via TLS session sumption, which allows abbreviating TLS handshakes by leveraging resumptions is feasible, we also looked into DNS data to understand key material exchanged in an earlier TLS session. -

Non Basta Avere Un Computer Potente, L'ultimo Modello Di Tablet O

Non basta avere un computer potente, l’ultimo modello di tablet o il sistema operativo più aggiornato; 100 per sfruttarli al massimo servono anche applicazioni, servizi e utility capaci di semplificare e velocizzare le operazioni quotidiane. 78 PC Professionale / Settembre 2017 078-117_Art_Freeware_318.indd 78 30/08/17 12:04 100FREE WARE APP E SERVIZI GRATUITI ● Di Dario Orlandi 078-117_Art_Freeware_318.indd 79 30/08/17 12:04 PROVE / FREEWARE / IL TEMPO IN CUI I SISTEMI OPERATIVI SI DAVANO BATTAGLIA SUL FRONTE DELLE FUNZIONI INTEGRATE È ORMAI PASSATO: PERFINO I DISPOSITIVI MOBILE LASCIANO ORMAI ALL’UTENTE LA FACOLTÀ DI SCEGLIERE GLI STRUMENTI E LE APPLICAZIONI PREFERITE, SCEGLIENDOLE TRA QUELLE DISPONIBILI, ANCHE GRATUITAMENTE, NEI RELATIVI STORE. MA PER TROVARE GLI STRUMENTI MIGLIORI BISOGNA CONOSCER- LI, PROVARLI E CONFRONTARLI. ED È PROPRIO QUELLO CHE ABBIAMO FATTO PER PREPARARE QUESTO ARTICOLO: ABBIAMO INSTALLATO E TESTATO MOLTE DECINE DI APPLICAZIONI, UTILITY E SERVIZI, ALLA RICERCA DELLE SOLUZIONI MIGLIORI PER SODDISFARE LE ESIGENZE DELLA FETTA DI UTENTI PIÙ AMPIA POSSIBILE. ABBIAMO CONCENTRATO L’ATTENZIONE SOLO SUI SOFTWARE GRATUITI, PER PROPORRE UNA COLLEZIONE COMPLETA CHE NON INCIDA SUL PORTAFOGLIO. La diffusione dei sistemi opera- un forte ritardo nei confronti di Lo Store che Microsoft di Windows sono ancora in gran tivi mobile ha reso evidente uno tutti gli altri sistemi operativi: le parte abbandonati a loro stessi: dei difetti storici di Windows: distribuzioni Linux offrono da ha creato per le devono individuare, selezionare l’assenza di un sistema di distri- decenni funzioni dedicate alla ge- applicazioni Windows si e installare i programmi senza buzione e aggiornamento auto- stione dei pacchetti, affiancate in sta lentamente popolando, alcun aiuto da parte del sistema matico per i software di terze seguito da interfacce di gestione operativo. -

Forensic Investigation of User's Web Activity on Google Chrome Using

IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, VOL.16 No.9, September 2016 123 Forensic Investigation of User’s Web Activity on Google Chrome using various Forensic Tools Narmeen Shafqat, NUST, Pakistan Summary acknowledged browsers like Internet Explorer, Google Cyber Crimes are increasing day by day, ranging from Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Safari, Opera etc. but should confidentiality violation to identity theft and much more. The also have hands on experience of less popular web web activity of the suspect, whether carried out on computer or browsers like Erwise, Arena, Cello, Netscape, iCab, smart device, is hence of particular interest to the forensics Cyberdog etc. Not only this, the forensic experts should investigator. Browser forensics i.e forensics of suspect’s browser also know how to find artifacts of interest from older history, saved passwords, cache, recent tabs opened etc. , therefore supply ample amount of information to the forensic versions of well-known web browsers; Internet Explorer, experts in case of any illegal involvement of the culprit in any Chrome and Mozilla Firefox atleast, because he might activity done on web browsers. Owing to the growing popularity experience a case where the suspected person is using and widespread use of the Google Chrome web browser, this older versions of these browsers. paper will forensically analyse the said browser in windows 8 According to StatCounter Global market share for the web environment, using various forensics tools and techniques, with browsers (2015), Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox and the aim to reconstruct the web browsing activities of the suspect. Microsoft’s Internet Explorer make up 90% of the browser The working of Google Chrome in regular mode, private usage. -

Anti-Mapa De Privacidade

Anti-mapa de privacidade Feito para você não ser rastreado Organização: Bárbara Simão e Rafael Zanatta Pesquisa e produção de textos: Bárbara Simão, Juliana Oms, Livia Torres e Rafael Zanatta Revisão: Rafael Zanatta Revisão de texto: Bárbara Prado Simão Design: Talita Patricio Martins Realização Supervisão: Carla Yue e Teresa Liporace Coordenação executiva: Elici Bueno Idec - Instituto Brasileiro de Defesa do Consumidor Rua Desembargador Guimarães, 21 - Água Branca CEP 05002-050 - São Paulo-SP Telefone: 11 3874-2150 [email protected] www.idec.org.br Por que um anti-mapa? Há quem diga que dados O mercado de dados funciona Esta situação gera sérias pessoais são o “petróleo assim: empresas desenvolvem consequências para o modo da era digital”. Enquanto modelos para prever nossos como vivemos e nossa isolados, não representam comportamentos, identificar democracia. Por isso, a muita coisa nem possuem nossas preferências e nos aprovação da Lei Geral tanto valor, mas quando influenciar com propagandas de Dados Pessoais foi tão integrados e analisados em especialmente direcionadas importante: nossos dados conjunto revelam perfis de para nós, pois sabem deixarão de ser objetos consumo, de crédito, hábitos aquilo que nos sensibiliza a passíveis de extração, pois recorrentes e até padrões de partir de nosso padrão de são parte de nós e de quem personalidade. comportamento - situação somos. Ao prever princípios muitas vezes despercebida. éticos e direitos básicos aos Estes perfis que criam de nós cidadãos, a lei nos devolve podem até gerar discriminação o controle sobre todas as com preços diferenciados, por informações que produzimos exemplo, a partir do local onde - é como o Código de Defesa realizamos a compra ou da do Consumidor para as novas renda obtida. -

Confessional Reflexivity As Introspection and Avowal

Establishing the ‘Truth’ of the Matter: Confessional Reflexivity as Introspection and Avowal JOSEPH WEBSTER University of Edinburgh The conceptualisation of reflexivity commonly found in social anthropology deploys the term as if it were both a ‘virtuous’ mechanism of self‐reflection and an ethical technique of truth telling, with reflexivity frequently deployed as an moral practice of introspection and avowal. Further, because reflexivity is used as a methodology for constructing the authority of ethnographic accounts, reflexivity in anthropology has come to closely resemble Foucault’s descriptions of confession. By discussing Lynch’s (2000) critical analysis of reflexivity as an ‘academic virtue’, I consider his argument through the lens of my own concept of ‘confessional reflexivity’. While supporting Lynch’s diagnosis of the ‘problem of reflexivity’, I attempt to critique his ethnomethodological cure as essentialist, I conclude that a way forward might be found by blending Foucault’s (1976, 1993) theory of confession with Bourdieu’s (1992) theory of ‘epistemic reflexivity’. The ubiquity of reflexivity and its many forms For as long as thirty years, reflexivity has occupied a ‘place of honour’ at the table of most social science researchers and research institutions. Reflexivity has become enshrined as a foundational, or, perhaps better, essential, concept which is relied upon as a kind of talisman whose power can be invoked to shore up the ‘truthiness’ of the claims those researchers and their institutions are in the business of making. No discipline, it seems, is more guilty of this ‘evoking’ than social anthropology (Lucy 2000, Sangren 2007, Salzaman 2002). Yet, despite the ubiquity of its deployment in anthropology, the term ‘reflexivity’ remains poorly defined. -

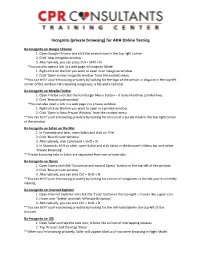

Incognito (Private Browsing) for AHA Online Testing

Incognito (private browsing) for AHA Online Testing Go Incognito on Google Chrome 1. Open Google Chrome and click the wrench icon in the top right corner. 2. Click ‘new incognito window’. 3. Alternatively, you can press Ctrl + Shift + N. *You can also open a link in a web page in Incognito Mode. 1. Right-click on the link you want to open in an Incognito window. 2. Click ’Open in new incognito window’ from the context menu. **You can tell if you’re browsing privately by looking for the logo of the person in disguise in the top-left corner of the window. He’s wearing sunglasses, a hat and a raincoat. Go Incognito on Mozilla Firefox 1. Open Firefox and click the hamburger Menu button – it looks like three parallel lines. 2. Click ‘New private window’. *You can also open a link in a web page in a private window. 1. Right-click on the link you want to open in a private window. 2. Click ’Open in New Private Window’ from the context menu. **You can tell if you’re browsing privately by looking for an icon of a purple mask in the top-right corner of the window. Go Incognito on Safari on the Mac 1. In Yosemite and later, open Safari and click on ‘File’. 2. Click ‘New Private Window’. 3. Alternatively, click Command + Shift + N. 4. In Mavericks 10.9 or older, open Safari and click Safari in the browser’s Menu bar and select ‘Private Browsing’. **Private browsing tabs in Safari are separated from non-private tabs. -

General Characteristics of Android Browsers with Focus on Security and Privacy Features

BÁNKI KÖZLEMÉNYEK 3. ÉVFOLYAM 1. SZÁM General characteristics of Android browsers with focus on security and privacy features Petar Čisar*, Sanja Maravic Cisar**, Igor Fürstner*** Academy of Criminalistic and Police Studies, Belgrade, Serbia, **Subotica Tech, Subotica, Serbia, ***Óbuda University, Bánki Donát Faculty of Mechanical and Safety Engineering, Budapest, Hungary, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] • Incognito browsing mode - offers real private Abstract —Satisfactory level of security in the use of the browsing experience without leaving any historical Internet in mobile devices depends on several factors. One of data. them is safe browsing. A key factor in providing secure • Using of HTTPS protocol - enforces SSL (Secure browsing is the application of a browser with the appropriate Socket Layer) security protocol (using of certificates) methods applied: clearing cookies, cache and history, ability wherever that’s possible. of incognito browsing, using of whitelists and encryptions and others. This paper presents an overview of the various • Disabling features like JavaScript, DOM (Document security and privacy features used in the most frequently Object Model) storage used Android browsers. Also, in the case of several browsers • Using fingerprinting techniques and types of mobile devices, the use of benchmark tests is Further sections of this paper provide an overview of the shown. Bearing in mind the differences, when choosing a applied security and privacy methods for more popular browser, special attention should be paid to the applied Android browsers. Also, in order to compare the adequate security and privacy features. features of browsers, the use of benchmark tests on different mobile devices will be shown. -

An Analysis of Private Browsing Modes in Modern Browsers

An Analysis of Private Browsing Modes in Modern Browsers Gaurav Aggarwal Elie Bursztein Collin Jackson Dan Boneh Stanford University CMU Stanford University Abstract Even within a single browser there are inconsistencies. We study the security and privacy of private browsing For example, in Firefox 3.6, cookies set in public mode modes recently added to all major browsers. We first pro- are not available to the web site while the browser is in pose a clean definition of the goals of private browsing private mode. However, passwords and SSL client cer- and survey its implementation in different browsers. We tificates stored in public mode are available while in pri- conduct a measurement study to determine how often it is vate mode. Since web sites can use the password man- used and on what categories of sites. Our results suggest ager as a crude cookie mechanism, the password policy that private browsing is used differently from how it is is inconsistent with the cookie policy. marketed. We then describe an automated technique for Browser plug-ins and extensions add considerable testing the security of private browsing modes and report complexity to private browsing. Even if a browser ad- on a few weaknesses found in the Firefox browser. Fi- equately implements private browsing, an extension can nally, we show that many popular browser extensions and completely undermine its privacy guarantees. In Sec- plugins undermine the security of private browsing. We tion 6.1 we show that many widely used extensions un- propose and experiment with a workable policy that lets dermine the goals of private browsing.