THE EVOLUTION of the ROMANTIC BALLET: the LIBRETTI and ENCHANTER CHARACTERS of SELECTED ROMANTIC BALLETS from the 1830S THROUGH the 1890S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Dancer Taking Leap Into World of Professional Ballet Vancouver Native Eyeing the Crown at International Contest

Young dancer taking leap into world of professional ballet Vancouver native eyeing the crown at international contest Vancouver native Derek Drilon, currently between gigs with the Joffrey and Boston Ballet companies, will dance with his home school, Northwest Classical Ballet, on June 18. (Courtesy of Northwest Classical Ballet) By Scott Hewitt, Columbian Arts & Features Reporter Published: June 10, 2016, 6:04 AM It’s good to be the prince. “I like playing princely roles. It feels pretty natural to me,” said Derek Drilon, 19. That makes sense. At age 19, the Vancouver native recently assumed a position of young royalty in the largest international dance competition in the world. The Youth America Grand Prix draws thousands of aspiring ballet dancers to regional semi- final competitions in cities all over the world, where professional judges evaluate each dancer’s performance, potential and artistry. Finalists are invited to New York City for the final contest, with prizes of scholarship money to the world’s leading dance academies and the invaluable contacts and connections that follow. Drilon won the semi-final Grand Prix Award in Chicago and was named one of the top six men in the New York finals, for his performance of the Siegfried Variation from “Swan Lake.” In Tchaikovsky’s ballet, Prince Siegfried is enraptured with a woman who has been transformed into a swan — but then falls under the spell of a pretender, with tragic consequences. The prince’s famously expressive solo dance, as he considers his predicament and his passion, require great power and artistry. Comedy is a whole different challenge. -

The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’S Split Sides

Spring 2012 Ball et Review The Caramel Variations by Ian Spencer Bell from Ballet Review Spring 2012 Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener in Merce Cunningham’s Split Sides . © 2012 Dance Research Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Moscow – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Oslo – Peter Sparling 9 Washington, D. C. – George Jackson 10 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 12 Toronto – Gary Smith 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 Toronto – Gary Smith 17 New York – George Jackson Ian Spencer Bell 31 18 The Caramel Variations Darrell Wilkins 31 Malakhov’s La Péri Francis Mason 38 Armgard von Bardeleben on Graham Don Daniels 41 The Iron Shoe Joel Lobenthal 64 46 A Conversation with Nicolai Hansen Ballet Review 40.1 Leigh Witchel Spring 2012 51 A Parisian Spring Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Francis Mason Managing Editor: 55 Erick Hawkins on Graham Roberta Hellman Joseph Houseal Senior Editor: 59 The Ecstatic Flight of Lin Hwa-min Don Daniels Associate Editor: Emily Hite Joel Lobenthal 64 Yvonne Mounsey: Encounters with Mr B 46 Associate Editor: Nicole Dekle Collins Larry Kaplan 71 Psyché and Phèdre Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Sandra Genter Photographers: 74 Next Wave Tom Brazil Costas 82 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 89 More Balanchine Variations – Jay Rogoff Associates: Peter Anastos 90 Pina – Jeffrey Gantz Robert Gres kovic 92 Body of a Dancer – Jay Rogoff George Jackson 93 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 71 100 Check It Out Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover Photograph by Stephanie Berger, BAM : Silas Riener Sarah C. -

Study of the Body Dimensions of Elite Professional Ballet Dancers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Documento descargado de http://www.apunts.org el 25/01/2011. Copia para uso personal, se prohíbe la transmisión de este documento por cualquier medio o formato. provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert 3 ORIGINAL ARTICLES Study of the body dimensions of elite professional ballet dancers HAMLET BETANCOURT LEÓNa, JULIETA ARÉCHIGA VIRAMONTESb, CARLOS MANUEL RAMÍREZ GARCÍAc AND MARIA ELENA DÍAZ SÁNCHEZd aAutonomous Metropolitan University. Iztapalapa Unit. México. bInstitute of Anthropological Research. UNAM. Mexico. bNational Technical Institute. Mexico. cInstitute of Nutrition and Food Hygiene. Cuba. ABstract RESUMEN The similarities and differences in the body dimensions of a Las diferencias o similitudes referidas a los tamaños absolu- group of ballet dancers compared with those of modern or tos de un grupo de bailarines de ballet frente a bailarines de folklore dances are indicators of corporal heterogeneity or danza moderna y folclórica son indicadores de variabilidad homogeneity and of the spatial volume occupied by a group o de la homogeneidad corporal y de la expresión del volu- of dancers. The present study aimed to analyze the kinan- men espacial que ocupa un grupo de danzantes. Este traba- thropometric similarities and differences among elite pro- jo se propuso analizar las similitudes y las diferencias ci- fessional ballet dancers compared with modern and folk- neantropométricas de los tamaños absolutos entre los lore dancers. The anthropometric profiles of dancers from bailarines profesionales de elite de ballet respecto a los de the National Ballet, National Dance and National Folkloric danza moderna y folclórica. -

Dance Etiquette Sheet 15

With the exception of dance shoes, many of the required code items and hair supplies are available for sale in our Pro Shop. Welcome! We are so happy to have you in our dance program. Together, we will work to instill a love of dance that can last a lifetime. Please review the following guidelines, and let us know if you have any questions. PROPER ATTIRE: HAIR: For ALL Ballet classes (Dance Tots, PreBallet, Ballet), hair must be pulled away from the face and pinned securely into a ballet bun (no bangs for ages 6 and up). For ALL other classes, hair must be in a ponytail, secured off the shoulders and away from the face. ALL CLASSES: NO LOOSE CLOTHES OVER LEOTARDS! TINY DANCERS: Female – Non-baggy athletic shorts & t-shirt. Dance attire (leotard, tights, ballet slippers**) may be worn if desired. Bare feet. Hair must be pulled away from face into a ponytail. Male – Non-baggy athletic shorts & t-shirt. Bare feet. Parents – Comfortable clothes that you can move in! Bare feet. DANCE TOTS: Female – Light pink leotard*, light pink footed tights**, pink leather ballet slippers*** Male – White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers PREBALLET: Female – Light blue leotard*, light pink footed tights**, pink leather ballet slippers*** Male - White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers CLASSICAL BALLET: Female – Black leotard*, light pink footed tights, pink leather ballet slippers** Male – White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers *All leotards for Dance Tots, PreBallet, and Classical Ballet must be simple in style – preferably tank, cap, or short sleeve. -

Proper Attire

2021-2022 Welcome! We are so happy to have you in our dance program. Together, we With the exception of dance shoes, will work to instill a love of dance that can last a lifetime. Please review the many of the required dancewear following guidelines and let us know if you have any questions. items and hair supplies are available for sale in our Pro Shop. PROPER ATTIRE: HAIR: For ALL Ballet classes (Dance Tots, Fairytale Ballerinas, PreBallet, Ballet), hair must be pulled away from the face and pinned securely into a ballet bun (no bangs for ages 6 and up). For ALL other classes, hair must be in a ponytail, secured off the shoulders and away from the face. ------------------------------------------ ------ TEENY DANCERS: Female – Non-baggy athletic/bike shorts & t-shirt. Bare Feet. Dance attire (leotard, tights, ballet slippers**) may be worn if desired. Male – Non-baggy athletic/bike shorts & t-shirt. Bare feet. Parents – Comfortable clothes that you can move in! Bare feet. DANCE TOTS: Female – Light pink leotard*, light pink footed tights**, pink leather ballet slippers*** Male – White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers PREBALLET: Female – Light blue leotard*, light pink footed tights**, pink leather ballet slippers*** Male - White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers PRE-TAP/HIP-HOP: Female – Light blue leotard, light pink OR light suntan footed tights**. Tan Tap Shoes / Tan Slip-on Jazz Shoes. • Optional – Girls may also wear light blue or black dance skirt or dance shorts over their leotard & tights. Male - White t-shirt, black bike shorts, Black crew socks. -

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon Du Diable

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Edited and Introduced by Robert Ignatius Letellier Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable, Edited by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3608-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3608-1 Cesare Pugni in London (c. 1845) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................... ix Esmeralda Italian Version La corte del miracoli (Introduzione) .......................................................................................... 2 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................. 5 Sposalizio di Esmeralda ............................................................................................................. 6 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................ -

Gothic Riffs Anon., the Secret Tribunal

Gothic Riffs Anon., The Secret Tribunal. courtesy of the sadleir-Black collection, University of Virginia Library Gothic Riffs Secularizing the Uncanny in the European Imaginary, 1780–1820 ) Diane Long hoeveler The OhiO STaTe UniverSiT y Press Columbus Copyright © 2010 by The Ohio State University. all rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data hoeveler, Diane Long. Gothic riffs : secularizing the uncanny in the european imaginary, 1780–1820 / Diane Long hoeveler. p. cm. includes bibliographical references and index. iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-1131-1 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-10: 0-8142-1131-3 (cloth : alk. paper) iSBn-13: 978-0-8142-9230-3 (cd-rom) 1. Gothic revival (Literature)—influence. 2. Gothic revival (Literature)—history and criticism. 3. Gothic fiction (Literary genre)—history and criticism. i. Title. Pn3435.h59 2010 809'.9164—dc22 2009050593 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (iSBn 978-0-8142-1131-1) CD-rOM (iSBn 978-0-8142-9230-3) Cover design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Type set in adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Thomson-Shore, inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the american national Standard for information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSi Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is for David: January 29, 2010 Riff: A simple musical phrase repeated over and over, often with a strong or syncopated rhythm, and frequently used as background to a solo improvisa- tion. —OED - c o n t e n t s - List of figures xi Preface and Acknowledgments xiii introduction Gothic Riffs: songs in the Key of secularization 1 chapter 1 Gothic Mediations: shakespeare, the sentimental, and the secularization of Virtue 35 chapter 2 Rescue operas” and Providential Deism 74 chapter 3 Ghostly Visitants: the Gothic Drama and the coexistence of immanence and transcendence 103 chapter 4 Entr’acte. -

'In Ballet You Need to Be Perfect'

‘In ballet you need to be perfect’ Ivan Vasiliev Rudolph Nureyev Ivan Vasiliev is a Russian ballet dancer. He is the principal dancer with the American Ballet Theatre. I live in a flat in St Petersburg with my girlfriend. I usually get up at about nine and then I have a shower. In my job I often stay in hotels. When you have a shower in the morning in a hotel you can leave your towel on the floor. I love that! I always have a good breakfast, and I love eggs. When I am very hungry, I sometimes eat five. I like sausages, too. Classes start at 10.30. I practise all morning without a break. I sometimes have lunch, but not always. In the afternoon, I practise more. Of course in ballet, you need to be perfect. Nureyev is my favourite dancer. I have a pair of his ballet shoes. After work I want to eat. I love meat. My favourite is a big steak. No vegetables. Only steak. English File third edition Beginner • Student’s Book • Unit 6B, p.37 © Oxford University Press 2015 1 In the evening we sometimes go out. Before we go out my girlfriend looks at my clothes and she usually says: “No, Ivan. Change!” I’m not interested in clothes, but I love watches. I have seven, including a Montblanc, three Rolexes, and a Maurice Lacroix. Sometimes, I don’t go to bed until 1.00 or 2.00. It’s often difficult to sleep. I have a lot of things in my head. -

A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov

Spring 2010 Ballet Revi ew From the Spring 2010 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland and Misha Chernov On the cover: New York City Ballet’s Tiler Peck in Peter Martins’ The Sleeping Beauty. 4 New York – Alice Helpern 7 Stuttgart – Gary Smith 8 Lisbon – Peter Sparling 10 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 11 New York – Sandra Genter 13 Ann Arbor – Peter Sparling 16 New York – Sandra Genter 17 Toronto – Gary Smith 19 New York – Marian Horosko 20 San Francisco – Paul Parish David Vaughan 45 23 Paris 1909-2009 Sandra Genter 29 Pina Bausch (1940-2009) Laura Jacobs & Joel Lobenthal 31 A Conversation with Gelsey Kirkland & Misha Chernov Marnie Thomas Wood Edited by 37 Celebrating the Graham Anti-heroine Francis Mason Morris Rossabi Ballet Review 38.1 51 41 Ulaanbaatar Ballet Spring 2010 Darrell Wilkins Associate Editor and Designer: 45 A Mary Wigman Evening Marvin Hoshino Daniel Jacobson Associate Editor: 51 La Danse Don Daniels Associate Editor: Michael Langlois Joel Lobenthal 56 ABT 101 Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Larry Kaplan 61 Osipova’s Season Photographers: 37 Tom Brazil Davie Lerner Costas 71 A Conversation with Howard Barr Subscriptions: Don Daniels Roberta Hellman 75 No Apologies: Peck &Mearns at NYCB Copy Editor: Barbara Palfy Annie-B Parson 79 First Class Teachers Associates: Peter Anastos 88 London Reporter – Clement Crisp Robert Gres kovic 93 Alfredo Corvino – Elizabeth Zimmer George Jackson 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Elizabeth Kendall 23 Paul Parish 100 Check It Out Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Cover photo by Paul Kolnik, New York City Ballet: Tiler Peck Sarah C. -

4Th MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE

th 4 MINDING ANIMALS CONFERENCE CIUDAD DE MÉXICO, 17 TO 24 JANUARY, 2018 SOCIAL PROGRAMME: ROYAL PEDREGAL HOTEL ACADEMIC PROGRAMME: NATIONAL AUTONOMOUS UNIVERSITY OF MEXICO Auditorio Alfonso Caso and Anexos de la Facultad de Derecho FINAL PROGRAMME (Online version linked to abstracts. Download PDF here) 1/47 All delegates please note: 1. Presentation slots may have needed to be moved by the organisers, and may appear in a different place from that of the final printed programme. Please consult the schedule located in the Conference Programme upon arrival at the Conference for your presentation time. 2. Please note that presenters have to ensure the following times for presentation to allow for adequate time for questions from the floor and smooth transition of sessions. Delegates must not stray from their allocated 20 minutes. Further, delegates are welcome to move within sessions, therefore presenters MUST limit their talk to the allocated time. Therefore, Q&A will be AFTER each talk, and NOT at the end of the three presentations. Plenary and Invited Talks – 45 min. presentation and 15 min. discussion (Q&A). 3. For panels, each panellist must stick strictly to a 10 minute time frame, before discussion with the floor commences. 4. Note that co-authors may be presenting at the conference in place of, or with the main author. For all co-authors, delegates are advised to consult the Conference Abstracts link on the Minding Animals website. Use of the term et al is provided where there is more than two authors of an abstract. 5. Moderator notes will be available at all front desks in tutorial rooms, along with Time Sheets (5, 3 and 1 minute Left). -

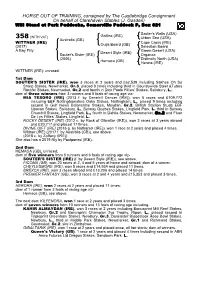

HORSE out of TRAINING, Consigned by the Castlebridge Consignment on Behalf of Clarehaven Stables (J

HORSE OUT OF TRAINING, consigned by The Castlebridge Consignment On behalf of Clarehaven Stables (J. Gosden) Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Somerville Paddock P, Box 821 Sadler's Wells (USA) Galileo (IRE) 358 (WITH VAT) Urban Sea (USA) Australia (GB) Cape Cross (IRE) WITTNER (IRE) Ouija Board (GB) (2017) Selection Board A Bay Filly Green Desert (USA) Desert Style (IRE) Souter's Sister (IRE) Organza (2006) Distinctly North (USA) Hemaca (GB) Herora (IRE) WITTNER (IRE): unraced. 1st Dam SOUTER'S SISTER (IRE), won 3 races at 2 years and £62,539 including Sakhee Oh So Sharp Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.3, placed 8 times including third in Countrywide Steel &Tubes Rockfel Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2 and fourth in Dick Poole Fillies’ Stakes, Salisbury, L.; dam of three winners from 3 runners and 5 foals of racing age viz- MIA TESORO (IRE) (2013 f. by Danehill Dancer (IRE)), won 5 races and £109,772 including EBF Nottinghamshire Oaks Stakes, Nottingham, L., placed 9 times including second in Gulf News Balanchine Stakes, Meydan, Gr.2, British Stallion Studs EBF Upavon Stakes, Salisbury, L., Betway Quebec Stakes, Lingfield Park, L. third in Betway Churchill Stakes, Lingfield Park, L., fourth in Dahlia Stakes, Newmarket, Gr.2 and Fluer De Lys Fillies’ Stakes, Lingfield, L. ROCKY DESERT (IRE) (2012 c. by Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)), won 2 races at 3 years abroad and £20,717 and placed 17 times. DIVINE GIFT (IRE) (2016 g. by Nathaniel (IRE)), won 1 race at 2 years and placed 4 times. Wittner (IRE) (2017 f. by Australia (GB)), see above. -

May 16, 2013 - Episode Introduction

May 16, 2013 - Episode Introduction French English Translation Bienvenue Welcome notre programme (m) hebdomadaire our weekly program tout le monde (m) everyone nos auditeurs (m) our listeners Cette semaine (f) This week nous parlons we talk about relevés (m) téléphoniques phone records elle a subie she underwent manifestations (f) protests exigences (f) salariales salary demands recettes (f) recipes aident à lutter contre help to fight against réchauffement (m) climatique global warming vont sauver le monde (m) will save the world Je savais I knew te passionnerait would excite you commencera par will start with contenant with premier groupe (m) first group passé simple (m) simple past Ensuite Then terminera par will end with rubrique (f) section sera dédiée à will be dedicated to Mettre to put sur la paille (f) on the straw C'est parti Let's go nourriture (f) food les autres sujets (m) d'actualité the other news stories Le département de la Justice américain obtient secrètement des relevés téléphoniques d'Associated Press French English Translation obtient secrètement secretely obtains relevés (m) téléphoniques phone records agence (f) de presse news agency avait secrètement rassemblé had secretly collected deux mois (m) two months relevés (m) téléphoniques phone records rédacteurs (m) en chef editors incluaient included appels (m) calls à partir de from plusieurs bureaux (m) several offices lignes (f) personnelles personal lines plusieurs membres (m) du personnel several staffers a qualifié called sans précédent (m) without precedent