Norse Greenland Settlement: Reflections on Climate Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Regional Distribution of Zeolites in the Basalts of the Faroe Islands and the Significance of Zeolites As Palaeo- Temperature Indicators

The regional distribution of zeolites in the basalts of the Faroe Islands and the significance of zeolites as palaeo- temperature indicators Ole Jørgensen The first maps of the regional distribution of zeolites in the Palaeogene basalt plateau of the Faroe Islands are presented. The zeolite zones (thomsonite-chabazite, analcite, mesolite, stilbite-heulandite, laumontite) continue below sea level and reach a depth of 2200 m in the Lopra-1/1A well. Below this level, a high temperature zone occurs characterised by prehnite and pumpellyite. The stilbite-heulan- dite zone is the dominant mineral zone on the northern island, Vágar, the analcite and mesolite zones are the dominant ones on the southern islands of Sandoy and Suðuroy and the thomsonite-chabazite zone is dominant on the two northeastern islands of Viðoy and Borðoy. It is estimated that zeolitisa- tion of the basalts took place at temperatures between about 40°C and 230°C. Palaeogeothermal gradients are estimated to have been 66 ± 9°C/km in the lower basalt formation of the Lopra area of Suðuroy, the southernmost island, 63 ± 8°C/km in the middle basalt formation on the northernmost island of Vágar and 56 ± 7°C/km in the upper basalt formation on the central island of Sandoy. A linear extrapolation of the gradient from the Lopra area places the palaeosurface of the basalt plateau near to the top of the lower basalt formation. On Vágar, the palaeosurface was somewhere between 1700 m and 2020 m above the lower formation while the palaeosurface on Sandoy was between 1550 m and 1924 m above the base of the upper formation. -

Reframing an Arctic Image, out of the Sublime

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2016-01-26 Reframing an Arctic Image, Out of the Sublime Thoreson, Kristine, Nicole Thoreson, K. (2016). Reframing an Arctic Image, Out of the Sublime (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27572 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/2779 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Reframing an Arctic Image, Out of the Sublime by Kristine Thoreson A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM OF ART CALGARY, ALBERTA January, 2016 © Kristine Thoreson 2016 Abstract A proliferation of sublime, mythic and nearly vacant landscape photographs of Arctic regions are circulating in museums and galleries internationally; artist monographs of these photographs are also readily available in major booksellers. Although the photographs are artfully crafted and technically superior, there is the question of what an accretion of so many sublime landscape images of the North accomplishes in terms of perceptions of place, community and culture? It is true that creating awe-inspiring photographs that promote an appreciation for polar-regions is legitimate work. -

Marine and Terrestrial Investigations in the Norse Eastern Settlement, South Greenland

Marine and terrestrial investigations in the Norse Eastern Settlement, South Greenland Naja Mikkelsen,Antoon Kuijpers, Susanne Lassen and Jesper Vedel During the Middle Ages the Norse settlements in included acoustic investigations of possible targets Greenland were the most northerly outpost of European located in 1998 during shallow-water side-scan sonar Christianity and civilisation in the Northern Hemisphere. investigations off Igaliku, the site of the Norse episco- The climate was relatively stable and mild around A.D. pal church Gardar in Igaliku Fjord (Fig. 2). A brief inves- 985 when Eric the Red founded the Eastern Settlement tigation of soil profiles was conducted in Søndre Igaliku, in the fjords of South Greenland. The Norse lived in a once prosperous Norse settlement that is now partly Greenland for almost 500 years, but disappeared in the covered by sand dunes. 14th century. Letters in Iceland report on a Norse mar- riage in A.D. 1408 in Hvalsey church of the Eastern Settlement, but after this account all written sources remain silent. Although there have been numerous stud- Field observations and preliminary ies and much speculation, the fate of the Norse settle- results ments in Greenland remains an essentially unsolved question. Sandhavn Sandhavn is a sheltered bay that extends from the coast north-north-west for approximately 1.5 km (Fig. 2). The entrance faces south-east and it is exposed to waves Previous and ongoing investigations and swells from the storms sweeping in from the Atlantic The main objective of the field work in the summer of around Kap Farvel, the south point of Greenland. -

The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E

Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 August 2016 The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E. Warden Oglethorpe University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur Part of the Canadian History Commons, European History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Warden, Donald E. (2016) "The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus," Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank my honors thesis committee: Dr. Michael Rulison, Dr. Kathleen Peters, and Dr. Nicholas Maher. I would also like to thank my friends and family who have supported me during my time at Oglethorpe. Moreover, I would like to thank my academic advisor, Dr. Karen Schmeichel, and the Director of the Honors Program, Dr. Sarah Terry. I could not have done any of this without you all. This article is available in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 Warden: Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Part I: Piecing Together the Puzzle Recent discoveries utilizing satellite technology from Sarah Parcak; archaeological sites from the 1960s, ancient, fantastical Sagas, and centuries of scholars thereafter each paint a picture of Norse-Indigenous contact and relations in North America prior to the Columbian Exchange. -

Jørgen Meldgaard's Film Works and Books on Art from the Arctic

Document generated on 09/24/2021 8:37 p.m. Études/Inuit/Studies Jørgen Meldgaard’s film works and books on art from the Arctic Les films de Jørgen Meldgaard et ses livres sur l’art de l’Arctique Anne Mette Jørgensen Volume 37, Number 1, 2013 Article abstract Danish archaeologist Jørgen Meldgaard (1927-2007) was a dedicated URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1025258ar filmmaker, and today’s archaeologists may find inspiration in his engagements DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1025258ar with the medium of film. He produced three major pieces of film work during his career. Filmed in very different styles, each illustrates a significant trend in See table of contents the scientific representation of the Other during the last half of the 20th century. This article analyses the films with particular attention to Meldgaard’s changing ways of engaging with the Inuit as objects and subjects, respectively. Publisher(s) It also compares Meldgaard’s films with his two books on Inuit art, and discusses his films in the context of contemporary methodological Association Inuksiutiit Katimajiit Inc. developments in archaeology and anthropology. It concludes by Centre interuniversitaire d’études et de recherches autochtones (CIÉRA) recommending that future archaeologists follow Meldgaard’s example and engage in sharing knowledge, through audiovisual media, with people affected ISSN by archaeological excavations, instead of letting media professionals take over the representation of archaeological knowledge. 0701-1008 (print) 1708-5268 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Jørgensen, A. M. (2013). Jørgen Meldgaard’s film works and books on art from the Arctic. -

Grønland Fra Syd Til Nord Landbosenior - September 2019 Grønland Fra Syd Til Nord - Qaqortoq Til Ilulissat

Grønland fra syd til nord LandboSenior - september 2019 Grønland fra Syd til Nord - Qaqortoq til Ilulissat Glæd dig til store oplevelser i arktiske Grønland når du med Rejsen begynder med en formidabel sejlads fra Narsarsuaq LandboSenior og Topas Travel kan rejse til verdens største ø. til Qaqortoq, som er en fantastisk smuk og frodig by og en af de mest fotogene i Grønland med de mange private haver. Efterårsfarver, nordlys, frostklare nætter og ingen myg Sydgrønland byder på ikke mindre end 5 UNESCO-steder, venter sammen med storslående natur- og kulturoplevelser. så oplevelserne står i kø, også af kulturel art. I Nuuk kan du Turen er særlig udviklet af Topas Travel til LandboSenior. f.eks. besøge Nationalmuseet. Naturoplevelserne er overvældende med høje bjerge, dybe I 2004 blev Ilulissat Isfjord optaget på UNESCOs fjorde og gletsjertunger, høje fjelde med de farvede huse og Verdensarvsliste. Og i 2017 blev ‘Kujataa Greenland’ med naturligvis gigantiske isbjerge. Og husk at holde udkig efter sine Nordboruiner og landbrugsområder optaget. Du skal hvaler og sæler på sejlturen op igennem Diskobugten til besøge begge steder på denne rejse – begge anerkendt for Ilulissat. deres rå skønhed og historie. Denne tur tager dig fra det frodige, grønne Grønland i syd til de smukke, gigantiske isbjerge i nord: 1200 km sejlads op langs Grønlands vestkyst med dejlige skib M/S Sarfaq Ittuk. Udover at nyde sejladsen, har du ved hvert stop undervejs rig mulighed for at udforske byer og bagland i det område, skibet lægger til, før der lettes anker og turen nordpå fortsættes. Program Dag 1. Afrejse fra Danmark og ankomst i Grønland Tirsdag 3. -

Ilulissat Icefjord

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1149.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Ilulissat Icefjord DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 7th July 2004 STATE PARTY: DENMARK CRITERIA: N (i) (iii) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 28th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (i): The Ilulissat Icefjord is an outstanding example of a stage in the Earth’s history: the last ice age of the Quaternary Period. The ice-stream is one of the fastest (19m per day) and most active in the world. Its annual calving of over 35 cu. km of ice accounts for 10% of the production of all Greenland calf ice, more than any other glacier outside Antarctica. The glacier has been the object of scientific attention for 250 years and, along with its relative ease of accessibility, has significantly added to the understanding of ice-cap glaciology, climate change and related geomorphic processes. Criterion (iii): The combination of a huge ice sheet and a fast moving glacial ice-stream calving into a fjord covered by icebergs is a phenomenon only seen in Greenland and Antarctica. Ilulissat offers both scientists and visitors easy access for close view of the calving glacier front as it cascades down from the ice sheet and into the ice-choked fjord. The wild and highly scenic combination of rock, ice and sea, along with the dramatic sounds produced by the moving ice, combine to present a memorable natural spectacle. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Located on the west coast of Greenland, 250-km north of the Arctic Circle, Greenland’s Ilulissat Icefjord (40,240-ha) is the sea mouth of Sermeq Kujalleq, one of the few glaciers through which the Greenland ice cap reaches the sea. -

Faroe Islands and Greenland 2008

N O R D I C M E D I A T R E N D S 10 Media and Communication Statistics Faroe Islands and Greenland 2008 Compiled by Ragnar Karlsson NORDICOM UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG 2008 NORDICOM’s activities are based on broad and extensive network of contacts and collaboration with members of the research community, media companies, politicians, regulators, teachers, librarians, and so forth, around the world. The activities at Nordicom are characterized by three main working areas. Media and Communication Research Findings in the Nordic Countries Nordicom publishes a Nordic journal, Nordicom Information, and an English language journal, Nordicom Review (refereed), as well as anthologies and other reports in both Nordic and English langu- ages. Different research databases concerning, among other things, scientific literature and ongoing research are updated continuously and are available on the Internet. Nordicom has the character of a hub of Nordic cooperation in media research. Making Nordic research in the field of mass communication and media studies known to colleagues and others outside the region, and weaving and supporting networks of collaboration between the Nordic research communities and colleagues abroad are two prime facets of the Nordicom work. The documentation services are based on work performed in national documentation centres at- tached to the universities in Aarhus, Denmark; Tampere, Finland; Reykjavik, Iceland; Bergen, Norway; and Göteborg, Sweden. Trends and Developments in the Media Sectors in the Nordic Countries Nordicom compiles and collates media statistics for the whole of the Nordic region. The statistics, to- gether with qualified analyses, are published in the series, Nordic Media Trends, and on the homepage. -

Nordics - Alberta Relations

Nordics - Alberta Relations This map is a generalized illustration only and is not intended to be used for reference purposes. The representation of political boundaries does not necessarily reflect the position of the Government of Alberta on international issues of recognition, sovereignty or jurisdiction. PROFILE NORDICS OVERVIEW . Danish, Norwegian and Swedish are the working languages of official Nordic co- Capital: Copenhagen (Nordic Council and . The Nordic countries are a geographical and operation. Council of Ministers Headquarters) cultural region in Northern Europe and the Northern Atlantic and include Denmark, Population: 26.7 million (2016) TRADE AND INVESTMENT Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, plus Languages: Danish, Faroese, Finnish, the associated territories of Greenland, the . The Nordic region is the world’s eleventh Greenlandic, Icelandic, Norwegian, Sami and Faroe Islands and the Åland Islands. largest economy. Swedish . The Nordic Council is a geo-political inter- . From 2012 to 2016, Alberta’s goods exports to Secretary-General of the Nordic Council: Britt parliamentary forum for co-operation between the Nordics averaged CAD $98.1 million per Bohlin Olsson (since 2014) the Nordic countries. It consists of 87 year. Top exports included machinery (CAD $31.6 million), nickel (CAD $12.5 million), President of the Nordic Council: Britt Lundberg representatives, elected from its members’ (elected for the year of 2017) parliaments. plastic (CAD $11.3 million), and food waste and animal feed (CAD $10.8 million). The Vice President of the Nordic Council: Juho . Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and export figures do not include trade in services Eerola (elected for the year of 2017) Sweden have been full members of the Nordic (e.g. -

Perceiving the Islandness of Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland)

Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, v7n1 — Grydehøj Islands as legible geographies: perceiving the islandness of Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland) Adam Grydehøj Ilisimatusark/University of Greenland, Greenland Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Island Dynamics, Denmark [email protected] Publication Information: Received 19 April 2018, Accepted 15 May 2018, Available online 30 June 2018 DOI: 10.21463/jmic.2018.07.1.01 Abstract Despite considerable research within the field of island studies, no consensus has yet been reached as to what it is that makes islands special. Around the world, islands and archipelagos are shaped by diverse spatialities and relationalities that make it difficult to identify clear general characteristics of islandness. This paper argues that one such ‘active ingredient’ of islandness, which is present across many forms of island spatiality, is the idea that islands are ‘legible geographies’: spaces of heightened conceptualisability, spaces that are exceptionally easy to imagine as places. The paper uses the case of Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland) to show how island geographical legibility has influenced a territory’s cultural and political development over time, even though Kalaallit Nunaat is such a large island that it can never be experienced as an island but can only be perceived as an island from a satellite or cartographic perspective. I ultimately argue that islandness can have significant effects on a place’s development but that it can be difficult to isolate these effects from other factors that may themselves have been influenced by islandness. Keywords archipelagos, Greenland, islands, islandness, Kalaallit Nunaat, legible geographies 2212-6821 © 2018 Institution for Marine and Island Cultures, Mokpo National University. -

COASTAL WONDERS of NORWAY, the FAROE ISLANDS and ICELAND Current Route: Oslo, Norway to Reykjavik, Iceland

COASTAL WONDERS OF NORWAY, THE FAROE ISLANDS AND ICELAND Current route: Oslo, Norway to Reykjavik, Iceland 17 Days National Geographic Resolution 126 Guests Expeditions in: Jun From $22,470 to $44,280 * Call us at 1.800.397.3348 or call your Travel Agent. In Australia, call 1300.361.012 • www.expeditions.com DAY 1: Oslo, Norway padding Arrive in Oslo and check into the Hotel Bristol (or 2022 Departure Dates: similar) in the heart of the city. On an afternoon tour, stroll amid the city’s famed Vigeland 6 Jun sculptures—hundreds of life-size human figures Advance Payment: set in terraced Frogner Park. Visit the Fram Museum, showcasing the polar ship Fram and $3,000 dedicated to the explorers and wooden vessels that navigated the Arctic Sea in the late 1800s and Sample Airfares: early 1900s. The evening is free to explore Oslo Economy: from $900 on your own. (L) Business: from $2,700 Charter(Oslo/Tromso): from $490 DAY 2: Oslo / Tromsø / Embark Airfares are subject to change padding Take a charter flight to Tromsø, known as the Cost Includes: “gateway to the Arctic” due to the large number of Arctic expeditions that originated here. Visit the One hotel night in Oslo; accommodations; Arctic Cathedral, where the unique architecture meals indicated; alcoholic beverages evokes icebergs; and peruse the Polar Museum, (except premium brands); excursions; which showcases the ships, equipment, and services of Lindblad Expeditions’ Leader, seafaring traditions of early Arctic settlers. Embark Naturalist staff and expert guides; use of our ship this afternoon. (B,L,D) kayaks; entrance fees; all port charges and service taxes; gratuities to ship’s crew. -

1617-Greenland Annular Eclipse 2021 ROLL.Indd

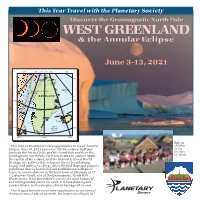

This Year Travel with the Planetary Society Discover the Geomagnetic North Pole WEST GREENLAND & the Annular Eclipse June 3-13, 2021 20°E 80°W 60°W 40°W 20°W 0° 20°E ARCTIC OCEAN CANADA1 2 20°E 0 2 , 0 1 e n u J - GREENLAND e s SEA p Qaanaaq i l c E GREENLAND 0° r a l 70°N u 70°N n BAFFIN n BAY A e h t f Arctic Circle o Disco Bay Ilulissat th a P Nuuk 60°N NORTH ATLANTIC 60°N OCEAN 40°W 40°W 20°W Ilulissat This is an extraordinary, rare opportunity to see an Annular children Eclipse, June 10, 2021, pass over NW Greenland, half way on the between the Arctic Circle and the North Pole and near the first day Geomagnetic North Pole. Fly from Iceland to explore Nuuk, of school the capital of Greenland, and the Ilulissat Icefjord World Heritage site at Disco Bay, reknown for its breathtaking beauty and miles of icebergs. Meet the sled dogs and puppies in Ilulissat. Stay in hotels in Nuuk and Ilulissat, with guest house accommodations in the Inuit town of Qaanaaq at 77 1/2 degrees North, site of the Geomagnetic North Pole Observatory. West Greenland is one of the most beautiful and unforgettable places on earth. It is breathtaking and extraordinary, with a unique cultural heritage all its own. This is quite literally a one-time opportunity to visit one of the most remote places on earth. We hope you will join us! Ilulissat & Disco Bay Itinerary Day 1/2 Depart USA for Reykjavik, Iceland Depart Newark or other IcelandAir gateway cities for Reykjavik, Iceland, arriving around 6:30 am on Day 2.