The Development of Radio and Radio Research Perspectives Towards a New Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viewing the Future U2

Annual Report 2011 Viewing the Future U2 VIEWING THE FUTURE 14 BROADCASTING GERMAN-SPEAKING 42 BROADCASTING INTERNATIONAL 128 DIGITAL & ADJACENT 214 CONTENT PRODUCTION & GLOBAL SALES R EPORTS FROM CONSOLIDATED THE EXECUTIVE FINANCIAL AND SUPER- STATEMENTS VISORY BOARD 130 I ncome Statement 131 S tatement of Comprehensive Income 16 LETTER FROM THE CEO 132 S tatement of Financial Position 18 M EMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE BOARD 133 C ash flow Statement 20 REPORT OF THE SUPERVISORY BOARD 134 S tatement in Changes in Equity 26 P roposed Allocation of Profits 135 N otes 26 M anagement Declaration and Corporate Governance Report 211 R esponsibility Statement of the Executive Board G ROUP MANAGE- 212 A uditor‘s Report MENT REPORT 44 T HE YEAR 2011 AT A GLANCE 46 B usiness Operations and Business ADDITIONAL Conditions 60 T- V HIGHLIGHTS 2011 INFORMATION 62 B usiness Performance 80 S egment Reporting 216 Key Figures: Multi-Year-Overview 83 E mployees 217 Finance Glossary 88 T o he Pr SiebenSat.1 Share 218 M edia Glossary 92 N on-Financial Performance 219 I ndex of Figures and Tables Indicators 221 E ditorial Information 98 PB U LIC VALUE 222 Financial Calendar 100 E vents after the Reporting Period 101 R isk Report 116 O utlook 120 P ROGRAMMING OUTLOOK FOR 2012 Klapper vorne innen U2 PROSIEBENSAT.1 AT A GLANCE The ProSiebenSat.1 Group was established in 2000 as the largest TV company in Germany. Today, we are present with 28 TV stations in 10 countries and rank among Europe‘s leading media groups. -

Towards Streamlined Broadcasting: the Changing Music Cultures of 1990 Finnish Commercial Radio

Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music doi:10.5429/2079-3871(2010)v1i1.8en Towards Streamlined Broadcasting: The Changing Music Cultures of 1990 Finnish Commercial Radio Heikki Uimonen [email protected] Dept. of Music Anthropology, University of Tampere Abstract The deregulation of broadcasting in 1985 Finland introduced competition between the European public service tradition and American commercial radio. Musically diverse and almost uncontrolled programme policies of the mid-1980s were replaced by the American-style format radio in the 1990s. The article focuses on how the process of music selection and radio music management changed. What were the economic, technological, organisational and cultural constraints that regulated the radio business and especially music? The question will be answered by empirical data consisting of interviews with the radio station personnel and music copyright reports supported by printed archive material. Key words: radio music, deregulation, music programming, play lists, music selection. Introduction Yleisradio (The Finnish Broadcasting Company, YLE) was founded in 1926. Right from the beginning music had an important role accounting for nearly 70 percent of broadcast time. Soon the share was cut down but it still remained around 50 percent. Publicly funded radio broadcast live; recordings were used very seldom. It seems that the YLE had two main guidelines in their programme policy: firstly to provide serious and uplifting popular education and information to the public and secondly to meet the listeners’ needs for entertainment. In practice this meant more highbrow than folksy style amusement (Kurkela, 2010, pp. 72– 73). In the early 1960s the YLE policy was challenged when the pirate stations started to broadcast off the coast of Stockholm. -

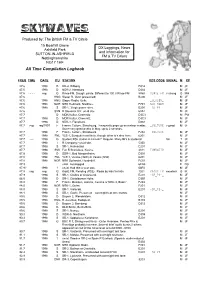

All Time Compilation Logbook by Date/Time

SKYWAVES Produced by: The British FM & TV Circle 15 Boarhill Grove DX Loggings, News Ashfield Park and Information for SUTTON-IN-ASHFIELD FM & TV DXers Nottinghamshire NG17 1HF All Time Compilation Logbook FREQ TIME DATE ITU STATION RDS CODE SIGNAL M RP 87.6 1998 D BR-4, Dillberg. D314 M JF 87.6 1998 D NDR-2, Hamburg. D382 M JF 87.6 - - - - reg G Rinse FM, Slough. pirate. Different to 100.3 Rinse FM 8760 RINSE_FM v strong GMH 87.6 HNG Slager R, Gyor (presumed) B206 M JF 87.6 1998 HNG Slager Radio, Gyšr. _SLAGER_ MJF 87.6 1998 NOR NRK Hedmark, Nordhue. F701 NRK_HEDM MJF 87.6 1998 S SR-1, 3 high power sites. E201 -SR_P1-_ MJF 87.6 SVN R Slovenia 202, un-id site. 63A2 M JF 87.7 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz D3C3 M PW 87.7 1998 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz. D3C3 M JF 87.7 1998 D NDR-4, Flensburg. D384 M JF 87.7 reg reg/1997 F France Culture, Strasbourg. Frequently pops up on meteor scatter. _CULTURE v good M JF Some very good peaks in May, up to 2 seconds. 87.7 1998 F France Culture, Strasbourg. F202 _CULTURE MJF 87.7 1998 FNL YLE-1, Eurajoki most likely, though other txÕs also here. 6201 M JF 87.7 ---- 1998 G Student RSL station in Lincoln? Regular. Many ID's & students! fair T JF 87.7 1998 I R Company? un-id site. 5350 M JF 87.7 1998 S SR-1, Halmastad. E201 M JF 87.7 1998 SVK Fun R Bratislava, Kosice. -

BR IFIC N° 2675 Index/Indice

BR IFIC N° 2675 Index/Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Part 1 / Partie 1 / Parte 1 Date/Fecha 10.08.2010 Description of Columns Description des colonnes Descripción de columnas No. Sequential number Numéro séquenciel Número sequencial BR Id. BR identification number Numéro d'identification du BR Número de identificación de la BR Adm Notifying Administration Administration notificatrice Administración notificante 1A [MHz] Assigned frequency [MHz] Fréquence assignée [MHz] Frecuencia asignada [MHz] Name of the location of Nom de l'emplacement de Nombre del emplazamiento de 4A/5A transmitting / receiving station la station d'émission / réception estación transmisora / receptora 4B/5B Geographical area Zone géographique Zona geográfica 4C/5C Geographical coordinates Coordonnées géographiques Coordenadas geográficas 6A Class of station Classe de station Clase de estación Purpose of the notification: Objet de la notification: Propósito de la notificación: Intent ADD-addition MOD-modify ADD-ajouter MOD-modifier ADD-añadir MOD-modificar SUP-suppress W/D-withdraw SUP-supprimer W/D-retirer SUP-suprimir W/D-retirar No. BR Id Adm 1A [MHz] 4A/5A 4B/5B 4C/5C 6A Part Intent 1 110073638 ARG 235.7500 PTO IGUAZU ARG 54W34'25'' 25S35'48'' FX 1 ADD 2 110072771 -

Commercial Radio As Music Culture Heikki Uimonen, University Of

This article has been published in a revised form in Popular Music https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143017000071. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution or re-use. © Cambridge University Press 2017. Beyond the Playlist: Commercial Radio as Music Culture Heikki Uimonen, University of the Arts Helsinki, Sibelius Academy [email protected] Abstract This article presents the historical transformation of Finnish commercial radio popular music policies from 1985–2005 and contemplates the role of terrestrial radio in contemporary digital age. It argues that a sender-centred paradigm of early commercial radio was replaced swiftly by receiver-centered paradigm, which has been applied since the early 1990s. The change of radio music cultures is described in detail by dividing it into three different eras: Block Radio, Format Radio, and Media Convergence. The study draws on the research project consisting of case studies analysing the music content of various radio stations. The primary empirical data is composed of thirty-two interviews of radio personnel and the analysis of 4,500 individual songs broadcast by popular music radio stations with newspaper and journal articles supporting the primary data. Radio music culture is approached theoretically from the ethnomusicological perspective and thus defined as all practices that have an effect on broadcast music, including the processes of acquiring, selecting, and governing music. The empirical results of the study show that the transformation of radio music cultures is affected by economic, technological, legal, organisational, and cultural factors. 1 Introduction In 1985, the first local and commercial radio stations in Finland were granted two-year experimental licences. -

Identity-Related Media Consumption

JENNIINA HALKOAHO Identity-Related Media Consumption A Focus on Consumers' Relationships with Their Favorite TV Programs ACTA WASAENSIA NO 261 ________________________________ BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION 106 MARKETING UNIVERSITAS WASAENSIS 2012 Reviewers Professor Outi Uusitalo Jyväskylä University School of Business and Economics P.O. Box 35 FI–40014 University of Jyväskylä Finland Professor Agneta Marell Umeå University Umeå School of Business SE–90187 Umeå Sweden III Julkaisija Julkaisuajankohta Vaasan yliopisto Toukokuu 2012 Tekijä(t) Julkaisun tyyppi Jenniina Halkoaho Monografia Julkaisusarjan nimi, osan numero Acta Wasaensia, 261 Yhteystiedot ISBN Vaasan yliopisto 978–952–476–396–7 Markkinoinnin yksikkö ISSN PL 700 0355–2667, 1235–7871 65101 VAASA Sivumäärä Kieli 271 englanti Julkaisun nimike Identiteettiä rakentava median kuluttaminen – Tarkastelussa kuluttajien suhteet suosikkitelevisio-ohjelmiinsa Tiivistelmä Mediat nousevat nyky-yhteiskunnassamme merkittävään roolin niin yksittäisinä kulutuk- sen kohteina kuin vaikutusvaltaisina kulttuurisina instituutioina. Tässä kulutustutkimuk- sen alaan sijoittuvassa tutkimuksessa tarkastellaan medioiden kuluttamista symbolisesta, erityisesti kuluttajan identiteetin rakentumisen näkökulmasta. Mediasisältöjä lähestytään tuotteina ja palveluina, joita kuluttajat voivat ostaa ja käyttää. Työn tarkoituksena on valaista kysymystä siitä, miten televisio-ohjelmat ja kuluttajan identiteetin rakentuminen ovat yhteydessä toisiinsa. Tutkielmassa pyritään tunnistamaan ja analysoimaan, millä tavoin kuluttajat -

Annual Report 2008 Key Figures

Annual Report 2008 Key Figures SBS consolidated as of July 2007 in EUR m Q4 Q1-Q4 2008 2007 2008 2007 Revenues 876.8 989.3 3,054.2 2,710.4 Recurring EBITDA* 279.3 296.9 674.5 662.9 EBITDA 251.7 281.1 618.3 522.3 EBIT 3.5 222.1 263.5 385.3 Net financial result -133.3 -79.6 -334.9 -135.5 Pre-tax loss/profit -128.0 142.4 -68.4 249.8 Consolidated net loss/profit -170.0 39.5 -129.1 89.4 Underlying net income** 78.2 75.4 170.4 272.8 Earnings per preferred share (EUR) -0.77 0.19 -0.58 0.42 Adjusted earnings per preferred share (EUR) 0.37 0.35 0.79 1.26 Cash flow from operating activities 433.2 646.0 1,352.4 1,600.4 Cash flow from investing activities -23.9 -432.1 -1,149.8 -3,275.8 Free cash flow 409.3 213.9 202.6 -1,675.4 Pro forma key figures 2008 (SBS consolidated as of January 2007) in EUR m Q1-Q4 2008 2007 Revenues 3,054.2 3,237.2 Recurring EBITDA* 674.5 784.2 EBITDA 618.3 628.2 Deconsolidation of Scandinavian Pay TV division C More in December 2008 * Recurring EBITDA: EBITDA before non-recurring items ** Underlying net income: Consolidated net result before effects of purchase price allocation amortizations of Euro 70.4 m (2007: Euro 82.8 m) and SBS impair- ment of Euro 180.0 m in 2008 as well as a not cash flow effective fx-valuation of Euro 66.6 m. -

12 000 Jonottaa Yhä Helsingiltä Asuntoa

TYÖ&RAHA URHEILU Marimekko Summanen lupaa pitää odotetusti tuotannon Leijonien edelleen luotsiksi ª ª UUSI JOHTO Suomessa KOLMEN VUODEN s/06 www.metrolehti.fi • 4. VUOSIKERTA • N:O 199 • TORSTAI 21. MARRASKUUTA 2002 SOPIMUKSEEN s/10 Tupakalle tulossa täysi 12 000 jonottaa yhä mainoskielto EU Europarlamentti hyväksyi ää- nin 311–208 tupakkamainonnan Helsingiltä asuntoa ja -sponsoroinnin täyskieltoa aja- van komission esityksen. Esitystä Kaupungin vuosittain aikana 16 000 asukkaalla. kun viime vuonna meni vain noin Myös yksityiset ja arava-vuok- vastustivat lähinnä konservatiivit Tuona aikana kaupungissa on 2 500 asuntoa. ramarkkinat ovat lisänneet suo- ja liberaalit. Suomalaisedustajat välittämien asuntojen jonottanut asuntoa keskimäärin – Sen kun tietäisi, miksi kas- siotaan. Tästä kertoo muun muas- kannattivat kieltoa. määrä laskenut 12 000 hakijaa vuodessa. vua ei ole tullut. Ehkä yksi syy on sa se, että viidesosa hakijoista kiel- Direktiivillä voidaan kieltää ra- Jono ei ole myöskään paisunut, se, että Helsingissä ostetaan ai- täytyi tarjotusta asunnosta viime jat ylittävä tupakkamainonta tie- HELSINKI Vuokra-asuntojono on vaikka välitettyjen asuntojen mää- empaa enemmän omistusasunto- vuonna. Suurin osa kieltäytymistä dotusvälineissä ja sponsorointi jämähtänyt Helsingissä vuoden rä on romahtanut tuhannella nel- ja, asuntoasiainosaston apulais- johtui siitä, että hakija oli saanut muun muassa urheilukisoissa. 1998 tasolle, vaikka kaupungin jän vuoden aikana. Vielä vuonna osastopäällikkö Markku Leijo poh- asunnon muualta ennen kau- – Tämä on suuri päivä kansan- väestö on noussut neljän vuoden 1998 asuntoja välitettiin 3 500, tii. pungin tarjousta. s/05 terveydelle ja selvä viesti tupak- kateollisuudelle. Mainonnan kiel- to suojaa nuorisoa siltä harha- luulolta, että tupakanpoltto olisi niin hienoa kuin mitä mainoksis- sa annetaan ymmärtää, terveys- komissaari David Byrne iloitsi. -

Finnish Broadcasting Company Annual Report 2005

ANNUAL REPORT YLEISRADIO OY 00024 Yleisradio Street address: Radiokatu 5, Helsinki Tel.: +358 9 14801 05 Fax: +358 9 1480 3215 www.yle.fi/fbc firstname.surname@yle.fi YLE CORPORATE COMMUNICATIONS Head of Corporate Communications Hilkka Hyrkkö PL 90, 00024 Yleisradio YLE ANNUAL REPORT 2005 Production: YLE Corporate Communications / Marja Niemi and YLE Corporate Finance Photographs: YLE Photo Service / Seppo Sarkkinen, Heli Sorjonen, Jyrki Valkama and Terho Anttolainen, Harri Hinkka, Marko Mäkinen, Heikki Oksanen, Tuula Pukkila, Sampo Rautamaa ja Kari Poppis Suomela Graphic design by Tähtikuviot Oy English translation by John Pickering Printed by Erweko Painotuote Oy March 2006 Channels p. 32-33 YLE TELEVISION p. 22-23 YLE RADIO 7 6 5 YLE Radio 1 The channel for culture, art and factual programmes. Its musical fare extends from classical and religious music through to jazz and folk. The channel carries concerts by the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra. 1 YLE YleX A multimedia channel for popular culture and new pop and rock. The fast-paced broadcast flow is complemented by special music programmes, comedy programmes and by profiled news broadcasts, including Pop News. 2 YLE Radio Suomi The national and regional news, service and contact channel, whose programming also focuses on sport and enter- tainment. Musical fare comprising domestic and foreign hits, tuneful adult rock as well as nostalgic pop. YLE YleQ A programme radio channel for in-depth radio speech and broad musical fare, characterised by an easy-going and focused style, with an emphasis on popular music and culture. YleQ can be heard in analogue format in Greater Helsinki and surroundings as well as via digital television in the digital reception area. -

Yleisradio Annual Report 2001

Annual Report 2001 YLE Annual Report 2001 Yleisradio Oy is a limited company engaged in public full opportunities to obtain information, to have new experi- service television and radio broadcasting. Its duties, operations ences and enjoyment and educate and develop themselves. and funding are defined by law. Together with its subsidiary YLE broadcasts programmes in Finnish and Swedish and responsible for distribution, Digita Oy, it forms a group. produces services in Sámi, Romany and sign language. YLE’s principal owner is the state. The annual report on YLE’s operation and the audience In accordance with its public service task, YLE endeav- report provide a picture of YLE in 2001. These publications ours in its programme operations to guarantee Finns equal appear in Finnish, Swedish and English (www.yle.fi/fbc). Key figures (EUR millions) YLE Group YLE Group YLE Group YLE YLE YLE 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 EXTENT OF OPERATION Turnover 381.0 361.8 346.3 334.7 335.3 333.6 % change 5.3 4.5 3.5 -0.2 0.5 Income 394.2 373.1 356.7 349.5 349.4 342.6 % change 5.6 4.6 2.1 0 2.0 3.6 Balance sheet total 522.2 462.1 466.5 484.6 496.6 471.8 Gross investments 42.0 45.2 46.6 50.7 67.3 52.5 % of income 10.6 12.1 13.1 14.5 19.3 15.3 Personnel 4511 4595 4582 4638 4658 4536 PROFITABILITY Profit/loss -108.6 -12.0 -17.2 -11.1 8.4 23.6 Profit/loss before extraordinary items -107.7 -11.4 -17.9 -9.7 9.6 23.8 SOURCES OF FUNDS AND FINANCIAL POSITION Quick ratio 1.5 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.3 Equity/Assets ratio % 51.5 53.2 55.6 57.0 57.6 57.7 Borrowed capital with -

Toimiluvanvarainen Radiotarjonta 2005 Yksityisten Analogisten Radiokanavien Sisältötarjonta 16 Suomalaiskaupungissa

LIIKENNE- JA VIESTINTÄMINISTERIÖN JULKAISUJA 4/2006 Viestintä Toimiluvanvarainen radiotarjonta 2005 Yksityisten analogisten radiokanavien sisältötarjonta 16 suomalaiskaupungissa Liikenne- ja viestintäministeriö Helsinki, 2006 KUVAILULEHTI Julkaisun päivämäärä 2.2.2006 Tekijät (toimielimestä: toimielimen nimi, puheenjohtaja, sihteeri) Julkaisun laji Marko Ala-Fossi Selvitys Toimeksiantaja Tampereen yliopisto, journalismin tutkimus- Liikenne- ja viestintäministeriö Toimielimen asettamispäivämäärä yksikkö Julkaisun nimi Toimiluvanvarainen radiotarjonta 2005. Yksityisten analogisten radiokanavien sisältötarjonta 16 suomalaiskaupungissa Tiivistelmä Hankkeessa on kehitetty suomalaisen radiotarjonnan kuvaamiseen ja analysoimiseen soveltuva tutkimusmalli, jolla on tutkittu yhteensä kuudentoista eri kaupungin toimiluvanvaraista radiotarjontaa. Aineistona on käytetty tutkimuskaupungeissa toimivien 38 yksityisen radioaseman arkipäivän lähetyksistä toukokuussa 2005 tehtyjä tallenteita ja niistä päivän parhaalta kuuntelujaksolta valittuja kuuden tunnin mittaisia näytteitä. Niistä yhteensä liki 70% oli musiikkia ja noin 20% puhetta eli toimituksellisen aineiston osuus oli kaikkiaan 89,7%. Liki neljännes kaikista näytteistä yhteensä oli ac/pop-musiikkia. Tärkein puhesisältöjen tyyppi taas olivat uutiset, joita oli yhteensä noin 4,7 % kaikista näytteistä. 1) Kaikkein puhepainotteisimmat kanavat olivat helsinkiläinen Lähiradio (80,7 %), turkulainen Radio Robin Hood ja kuopiolainen Oikea Asema. Uutisia lähettivät eniten Radio Robin Hood ja vammalalai- -

Paikallisradioita Suomeen!

Olli Ylönen Paikallisradioita Suomeen! Tampereen yliopisto Tiedotusopin laitos Julkaisuja/Publications Sarja/Series C 36/2002 2 ISBN 951-44-5572-X ISSN 1458-9613 3 Sisällysluettelo JOHDANTO.....................................................................................................5 1. PAIKALLISRADIOTOIMINNAN YLEISKUVA.................................6 1.1. Taustaa..........................................................................................6 1.2. Aloitus 1983-1986.......................................................................10 1.3. Suunnitelmat 1985..................................................................... 19 1.4. Toteutus 1985-1986.....................................................................28 1.5. Kehitys 1987-2000.......................................................................35 2. UUTISSISÄLLÖT.....................................................................................38 2.1. Aikaisemmat tutkimukset.................................................…… 38 2.2. Uutiset marraskuussa 2000.....................................…….……..40 2.3. Paikkakuntien uutiset: Helsinki, Tampere, Kotka, Rovaniemi…………………………….47 LOPUKSI........................................................................................................50 LÄHTEET LIITTEET Liite 1 Aloitushaastattelut Liite 2 Paikallisradiot vuodesta 1985 Liite 3 Nykyisin toimivat paikallisradiot Liite 4 Uutissisällöt marraskuussa 2000 4 5 JOHDANTO Tämän raportin lähtökohtana on Suomen Akatemian rahoittama tutkimushanke Media