The Metamorphosis of Bodily Discourse in Olympic Coverage in China: the “Sick Man of East Asia” and Chinese Nationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society Heather Langford Theses submitted for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Centre of Asian Studies University of Adelaide May 2009 ii Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the research requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Centre of Asian Studies School of Humanities and Social Sciences Adelaide University 2009 iii Table of Contents 1. Introduction.........................................................................................1 1.1. Literature Review..............................................................................13 1.2. Chapter summary ..............................................................................17 1.3. Conclusion ........................................................................................19 2. Background .......................................................................................20 2.1. Pre Han History.................................................................................20 2.2. Qin Dynasty ......................................................................................24 2.3. The Han Dynasty...............................................................................25 2.3.1. Trade with the West............................................................................. 30 2.4. Conclusion ........................................................................................32 3. Textiles and Technology....................................................................33 -

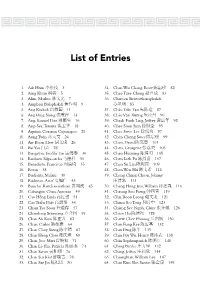

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

PDF, the Physics of Badminton

PAPER • OPEN ACCESS Related content - Physics of knuckleballs The physics of badminton Baptiste Darbois Texier, Caroline Cohen, David Quéré et al. To cite this article: Caroline Cohen et al 2015 New J. Phys. 17 063001 - On the size of sports fields Baptiste Darbois Texier, Caroline Cohen, Guillaume Dupeux et al. - Indeterminacy of drag exerted on an arrow in free flight: arrow attitude and laminar- View the article online for updates and enhancements. turbulent transition T Miyazaki, T Matsumoto, R Ando et al. Recent citations - Entropy of Badminton Strike Positions Javier Galeano et al - Kinetic and kinematic determinants of shuttlecock speed in the forehand jump smash performed by elite male Malaysian badminton players Yuvaraj Ramasamy et al - Multiple Repeated-Sprint Ability Test With Four Changes of Direction for Badminton Players (Part 2): Predicting Skill Level With Anthropometry, Strength, Shuttlecock, and Displacement Velocity Michael Phomsoupha and Guillaume Laffaye This content was downloaded from IP address 170.106.35.229 on 26/09/2021 at 03:47 New J. Phys. 17 (2015) 063001 doi:10.1088/1367-2630/17/6/063001 PAPER The physics of badminton OPEN ACCESS Caroline Cohen1, Baptiste Darbois Texier1, David Quéré2 and Christophe Clanet1 RECEIVED 1 LadHyX, UMR 7646 du CNRS, Ecole Polytechnique, 91128 Palaiseau Cedex, France 15 December 2014 2 PMMH, UMR 7636 du CNRS, ESPCI, 75005 Paris, France REVISED 20 March 2015 Keywords: physics of badminton, shuttlecock flight, shuttlecock flip, badminton trajectory ACCEPTED FOR PUBLICATION 31 March 2015 PUBLISHED 1 June 2015 Abstract The conical shape of a shuttlecock allows it to flip on impact. As a light and extended particle, it flies Content from this work with a pure drag trajectory. -

Entrevista a Lee Chong

ENTREVISTA A LEE CHONG WEI Traducció de l’entrevista apareguda a http://www.badminton-information.com/lee-chong- wei.html Lee Chong Wei és un jugador professional de bàdminton, nascut a Malàisia. Va guanyar la medalla de plata a les olimpíades de Pequí 2008, amb la qual cosa es va convertir en el primer malai en aconseguir arribar a una final olímpica a l’individual masculí, acabant amb la sequera de medalles per Malàisia des de les olimpíades de 1996. Com a jugador d’individual, va aconseguir per primer cop ser número 1 al rànquing mundial el 21 d’agost de 2008, posició que ostenta també a l’actualitat. És doncs el tercer jugador masculí malai que aconsegueix aquesta posició (Rashid Sidek i Roslin Hasim ho van aconseguir abans) i és l’únic del seu país que ha mantingut aquesta posició d’honor per més de dues setmanes. Lee és també l’actual campió de l’All England. Tot i haver guanyat diferents títols en importants competicions internacionals, com són varis Super Series, i malgrat el seu estatus entre l’elit mundial, només ha aconseguit la medalla de bronze (al 2005) en campionats del món. 1. A quina edat vas començar a jugar? Als 11 anys. 2. Sempre vas tenir la intenció de fer-te jugador professional? No, en absolut. Vaig començar a jugar de forma totalment natural, ja que el meu pare entrenava i em va animar a mi a fer-ho també. 3. Quan et vas adonar que eres suficientment bo com per donar “guerra” a nivell mundial? Em sembla que tenia 17 anys. -

CHINESE CHEMICAL LETTERS the Official Journal of the Chinese Chemical Society

CHINESE CHEMICAL LETTERS The official journal of the Chinese Chemical Society AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.1 • Editorial Board p.1 • Guide for Authors p.6 ISSN: 1001-8417 DESCRIPTION . Chinese Chemical Letters (CCL) (ISSN 1001-8417) was founded in July 1990. The journal publishes preliminary accounts in the whole field of chemistry, including inorganic chemistry, organic chemistry, analytical chemistry, physical chemistry, polymer chemistry, applied chemistry, etc., satisfying a real and urgent need for the dissemination of research results, especially hot topics. The journal does not accept articles previously published or scheduled to be published. To verify originality, your article may be checked by the originality detection service CrossCheck. The types of manuscripts include the original researches and the mini-reviews. The experimental evidence necessary to support your manuscript should be supplied for the referees and eventual publication as Electronic Supplementary Information. The mini-reviews are written by leading scientists within their field and summarized recent work from a personal perspective. They cover many exciting and innovative fields and are of general interest to all chemists. IMPACT FACTOR . 2020: 6.779 © Clarivate Analytics Journal Citation Reports 2021 ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING . Science Citation Index Expanded Chemical Abstracts Chemical Citation Index EDITORIAL BOARD . Editor-in-Chief Xuhong Qian, East China Normal University -

The Qin/Han Unification of China Course Description in Geography

Hum 230 Fall 2016 The Qin/Han Unification of China Course description In geography and cultural advances, the Qin and Han dynasties surpassed their predecessors, and together they number among the world’s greatest empires. This course examines their heritage through a selection of primary texts including the Confucian Analects, the enigmatic Dao de Jing, the cosmological Book of Changes, and the historical narrative tradition of Sima Qian’s Shi Ji. It samples cultural expression ranging from the poetic discourse of rhapsodies and pentasyllabic verse to the religious endeavors manifested in funerary artifacts. Alongside textual studies, this course explores the Han’s physical remains, including the ruins of its capitals, the Wu Liang shrine, and its important tombs. The Qin/Han portrays itself as a territorial, political, and cultural unifier, and it sets the benchmark against which all later dynasties must measure themselves. Course requirements 1. Reading and pondering all assigned readings before conferences. This will include regularly writing reading responses, discussion questions, poetic analyses, visual exploratories, and the like. 2. Attending all conferences, including regular, active and substantive conference participation. 3. Attending all lectures (which also means keeping 11:00-11:50 a.m. open on Wednesdays and Fridays for additional lectures or activities). All lectures meet in the Performing Arts Building, Rm 320, 11:00-11:50. 4. Three short (5-7 pages) analytical papers; deadlines & format will be set by conference leaders. 5. One group project; parameters to be established by individual conference leaders. Faculty Ken Brashier Conference leader ETC 203 x 7377 Alexei Ditter Lecturer E 423 x 7422 Douglas Fix Lecturer E 423 x 7422 Jing Jiang Chair E 119 x 7376 Hyong Rhew Lecturer E 122 x 7392 Michelle Wang Conference leader Lib 323 x 7730 Required texts Lewis, Mark E. -

20120619111449-1.Pdf

Organized by: State Key Laboratory of Polymer Physics and Chemistry, China Sponsored by: National Natural Science Foundation of China National Science Foundation, USA Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) Polymer Division, Chinese Chemical Society American Chemical Society Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, CAS University of Massachusetts BASF ChiMei ExxonMobil Henkel P&G SABIC Total ORGANIZATION Symposium Chair: Fosong Wang (China) Co-Chairs: Hiroyuki Nishide (Japan), Thomas J. McCarthy (USA), Harm-Anton Klok (Switzerland) International Advisory Committee: Ann-Christine Albertsson, Sweden Caiyuan Pan, China Yong Cao, China Coleen Pugh, USA Geoffrey W. Coates, USA Jiacong Shen, China Jan Feijen, Netherlands Zhiquan Shen, China Zhibin Guan, USA Benzhong Tang, China Charles C. Han, China Gregory N. Tew, USA James L. Hedrick, USA Mitsuru Ueda, Japan Akira Harada, Japan Karen L. Wooley, USA Yoshia Inoue, Japan Deyue Yan, China Ming Jiang, China Qifeng Zhou, China Jung-Il Jin, Korea Xi Zhang, China Timothy E. Long, USA Renxin Zhuo, China Krzysztof Matyjaszewski, USA Organizing Committee: Co-Chairs: Lixiang Wang, Yuesheng Li, Yanhou Geng, Zhaohui Su Members: Xuesi Chen, Yanxiang Cheng, Dongmei Cui, Jianhua Dong, Yanchun Han, Yubin Huang, Jin Ma, Tao Tang, Xianhong Wang, Zhiyuan Xie Secretariat Hui Tong, Guangping Su, Zhihua Ma CONTENTS Schedule overview……………………………………………………..1 Area map……………………………………………………………….2 General information……………………………………………………3 Symposium themes…………………………………………………….4 Program schedule………………………………………………………6 Posters………………………………………………………………...16 -

History of Badminton

Facts and Records History of Badminton In 1873, the Duke of Beaufort held a lawn party at his country house in the village of Badminton, Gloucestershire. A game of Poona was played on that day and became popular among British society’s elite. The new party sport became known as “the Badminton game”. In 1877, the Bath Badminton Club was formed and developed the first official set of rules. The Badminton Association was formed at a meeting in Southsea on 13th September 1893. It was the first National Association in the world and framed the rules for the Association and for the game. The popularity of the sport increased rapidly with 300 clubs being introduced by the 1920’s. Rising to 9,000 shortly after World War Π. The International Badminton Federation (IBF) was formed in 1934 with nine founding members: England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Denmark, Holland, Canada, New Zealand and France and as a consequence the Badminton Association became the Badminton Association of England. From nine founding members, the IBF, now called the Badminton World Federation (BWF), has over 160 member countries. The future of Badminton looks bright. Badminton was officially granted Olympic status in the 1992 Barcelona Games. Indonesia was the dominant force in that first Olympic tournament, winning two golds, a silver and a bronze; the country’s first Olympic medals in its history. More than 1.1 billion people watched the 1992 Olympic Badminton competition on television. Eight years later, and more than a century after introducing Badminton to the world, Britain claimed their first medal in the Olympics when Simon Archer and Jo Goode achieved Mixed Doubles Bronze in Sydney. -

The Old Master

INTRODUCTION Four main characteristics distinguish this book from other translations of Laozi. First, the base of my translation is the oldest existing edition of Laozi. It was excavated in 1973 from a tomb located in Mawangdui, the city of Changsha, Hunan Province of China, and is usually referred to as Text A of the Mawangdui Laozi because it is the older of the two texts of Laozi unearthed from it.1 Two facts prove that the text was written before 202 bce, when the first emperor of the Han dynasty began to rule over the entire China: it does not follow the naming taboo of the Han dynasty;2 its handwriting style is close to the seal script that was prevalent in the Qin dynasty (221–206 bce). Second, I have incorporated the recent archaeological discovery of Laozi-related documents, disentombed in 1993 in Jishan District’s tomb complex in the village of Guodian, near the city of Jingmen, Hubei Province of China. These documents include three bundles of bamboo slips written in the Chu script and contain passages related to the extant Laozi.3 Third, I have made extensive use of old commentaries on Laozi to provide the most comprehensive interpretations possible of each passage. Finally, I have examined myriad Chinese classic texts that are closely associated with the formation of Laozi, such as Zhuangzi, Lüshi Chunqiu (Spring and Autumn Annals of Mr. Lü), Han Feizi, and Huainanzi, to understand the intellectual and historical context of Laozi’s ideas. In addition to these characteristics, this book introduces several new interpretations of Laozi. -

Mansfield, Tanick & Cohen, P.A. Present a Roadmap for Business

CHINAInsight Fostering Business and Cultural Harmony between China and the U.S. VOL. 7 NO. 8 www.chinainsight.info SEPTEMBER 2008 Beijing Olympics a success won silver and the United States bronze). The results of the individual events were: Yang Wei – All-Around, Zou Kai – Floor Exercise, Xiao Qin – Pommel Horse, Li Xi- aopeng – Parallel Bars, Zou Kai – Horizon- tal Bar (U.S. gymnast Jonathan Horton won silver), and Chen Yibing – Rings (Yang Wei won sil- ver). The only apparatus that Chinese men Yang Wei did not medal in was the Vault. Leszak Blanik of Poland won that Moon Festival event. Page 3 The women’s artistic gymnastics team competition also saw China in the top spot on the medal podium. U.S. women Part of the opening ceremonies of the 2008 Beijing Olympics took silver and Romanian women won bronze. Chinese women performed well in By Jennifer Nordin, Staff Writer Artistic Gymnastics the individual events but were out-shined Chinese men dominated artistic gymnas- by Americans Nastia Liukin and Shawn he 2008 Beijing Olympics began tics in Beijing winning seven gold medals Johnson. In the All-Around competition, with a spectacular display at the including the team competition (Japan Olympics continues on Page 9 National Stadium (the Bird’s Nest) in the Opening Ceremonies Ton Aug. 8 and ended with an equally awe- inspiring Closing Ceremonies on Aug. 24. In between, was a 17-day rollercoaster of Mansfield, Tanick & emotion and excitement that only happens every four years. There were thrilling vic- tories and crushing defeats by the slimmest Cohen, P.A. -

Salsa2bills 1..3

By:AALaubenberg H.C.R.ANo.A37 CONCURRENT RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, A superb American athlete brought great honor to her 2 country and to Collin County when Nastia Liukin of Parker won five 3 medals in the gymnastics competition at the 2008 Olympic Games in 4 Beijing; and 5 WHEREAS, In a masterful demonstration of her grace and 6 athletic ability, Ms. Liukin claimed the gold medal in the Women 's 7 Individual All-Around Final and added two silver medals and one 8 bronze medal in individual events as well as a silver medal in the 9 team competition; her success tied the previous record for the most 10 medals won by a U.S. gymnast in one Olympics; and 11 WHEREAS, Anastasia Liukin was born on October 30, 1989, in 12 Moscow, Russia; her mother, Anna, was a world champion in rhythmic 13 gymnastics while her father, Valeri, won two gold medals and two 14 silver medals at the 1988 Olympic Games as a member of the Soviet 15 gymnastics team; when Nastia was two years old, the family moved to 16 the United States, where her parents began working as gymnastics 17 coaches; and 18 WHEREAS, While still very young, she began accompanying her 19 mother and father to the gym, where she amused herself by imitating 20 the routines of the older children training there; realizing that 21 Nastia 's talent and desire could not be ignored, her parents began 22 teaching her the fundamentals of the sport; throughout her career, 23 she has been coached by her father, a founder of the World Olympic 24 Gymnastics Academy, which has three locations in the Dallas-Fort 81R7070 JH-D 1 H.C.R.ANo.A37 1 Worth area, including the Plano gym where Nastia continues to 2 train; and 3 WHEREAS, Ms. -

China: an Unlikely Economic Hegemon

China: An Unlikely Economic Hegemon Heather Fox, Major, USAF Before any nation can achieve hegemon status, it must have economic strength. Numerous authors note that a strong economic base is the seed from which all other sources of national power emerge and hence can be considered a type of national foundation. Martin Jaques, for example, states that “military and political power rest on economic strength.”1 Economics forms the support base for national power, and major inter- national power shifts typically emerge as a result of economic develop- ments, not military power or political influence, as Paul Kennedy’s research into several centuries of global power politics highlights: There is detectable a causal relationship between the shifts which have occurred over time in the general economic and productive balances and the position occupied by individual powers in the international system . economic shifts heralded the rise of new Great Powers which would one day have a decisive impact upon the military/territorial order. This is why the move in global pro- ductive balances toward the “Pacific rim” which has taken place over the past few decades cannot be of interest merely to economists alone.2 China continues to grow economically at what some consider an alarming rate.3 Meanwhile, the United States, struggling with budget woes and sequestration, remains the world’s preeminent economic and military leader but in decline relative to China. The relationship between these two nations and the comparative power they possess may well lay the foundation for future global power shifts impacting not just China and the United States, but indeed the entire international community.4 However, while China is still expected to become extremely powerful, it may not rise to the level many expect due to three limiting factors: currency, exports, and demographics.