Selina Trieff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

Aaamc Issue 9 Chrono

of renowned rhythm and blues artists from this same time period lip-synch- ing to their hit recordings. These three aaamc mission: collections provide primary source The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, materials for researchers and students preservation, and dissemination of materi- and, thus, are invaluable additions to als for the purpose of research and study of our growing body of materials on African American music and culture. African American music and popular www.indiana.edu/~aaamc culture. The Archives has begun analyzing data from the project Black Music in Dutch Culture by annotating video No. 9, Fall 2004 recordings made during field research conducted in the Netherlands from 1998–2003. This research documents IN THIS ISSUE: the performance of African American music by Dutch musicians and the Letter ways this music has been integrated into the fabric of Dutch culture. The • From the Desk of the Director ...........................1 “The legacy of Ray In the Vault Charles is a reminder • Donations .............................1 of the importance of documenting and • Featured Collections: preserving the Nelson George .................2 achievements of Phyl Garland ....................2 creative artists and making this Arizona Dranes.................5 information available to students, Events researchers, Tribute.................................3 performers, and the • Ray Charles general public.” 1930-2004 photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Collection) photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Visiting Scholars reminder of the importance of docu- annotation component of this project is • Scot Brown ......................4 From the Desk menting and preserving the achieve- part of a joint initiative of Indiana of the Director ments of creative artists and making University and the University of this information available to students, Michigan that is funded by the On June 10, 2004, the world lost a researchers, performers, and the gener- Andrew W. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

BERTA WALKER GALLERY WELLFLEET Reception for The

BERTA WALKER GALLERY WELLFLEET 40 Main Street, Wellfleet, MA "Connected! Provincetown to Wellfleet" Artists of BWG Provincetown who live and create in Truro and Wellfleet Reception for the artists Wednesday, August 26, 2 to 4pm ROB DU TOIT, ROBERT HENRY, Selina Trieff "CONNECTED", 1996, oil on canvas, 48 x 72" GRACE HOPKINS, BRENDA HOROWITZ, PENELOPE JENCKS, JUDYTH KATZ, PAUL RESIKA, BLAIR RESIKA, SIDNEY SIMON, SELINA TRIEFF, PETER WATTS This exhibition is Dedicated to SELINA TRIEFF "Icon of the Provincetown Art Colony" WELLFLEET SUMMER HOURS: Daily 11-5; Saturday, 11- 8; closed Tuesday. Always by chance. Ample parking ROB DU TOIT, painter. TRURO . Rob DuToit was born in Boston Massachusetts in 1956, and began painting with oils and drawing with ink at the age of 10. Art writer Sue Harrison has observed: "DuToit's starkly beautiful works offer a fresh spontaneity while incorporating his classical training with layering and underglaze. They reflect a "sensitively for place that is reminiscent of work by Ross Moffett. And as in Moffett's work, you can feel the sweep of the land and the solidity of the hunkered down hills shaped by eons of wind off the water." His technique has emerged from his love of working with Chinese ROB DU TOIT pen and ink, and has enabled him to develop a meditative practice of painting as a way to further see things "as they are." ROBERT HENRY , painter, WELLFLEET . Henry came to Provincetown as a young art student to study with Hans Hofmann. During a career that has spanned over sixty years, Robert Henry has rarely repeated himself. -

The Wisconsin-Texas Jazz Nexus Jazz Wisconsin-Texas the the Wisconsin-Texas Jazz Nexus Nexus Jazz Wisconsin-Texas the Dave Oliphant

Oliphant: The Wisconsin Texas Jazz Nexus The Wisconsin-Texas Jazz Nexus Jazz Wisconsin-Texas The The Wisconsin-Texas Jazz Nexus Nexus Jazz Wisconsin-Texas The Dave Oliphant The institution of slavery had, of course, divided the nation, and Chicago. Texas blacks had earlier followed the cattle trails and on opposite sides in the Civil War were the states of Wis- north, but, in the 1920s, they also felt the magnetic pull of consin and Texas, both of which sent troops into the bloody, entertainment worlds in Kansas City and Chicago that catered decisive battle of Gettysburg. Little could the brave men of the to musicians who could perform the new music called jazz that Wisconsin 6th who defended or the determined Rebels of the had begun to crop up from New Jersey to Los Angeles, beholden Texas Regiments who assaulted Cemetery Ridge have suspected to but superseding the guitar-accompanied country blues and that, one day, musicians of their two states would join to pro- the repetitive piano rags. The first jazz recordings had begun to duce the harmonies of jazz that have depended so often on the appear in 1917, and, by 1923, classic jazz ensembles had begun blues form that was native to the Lone Star State yet was loved performing in Kansas City, Chicago, and New York, led by such and played by men from such Wisconsin towns and cities as seminal figures as Bennie Moten, King Oliver, Fletcher Jack Teagarden, courtesy of CLASSICS RECORDS. Teagarden, Jack Fox Lake, Madison, Milwaukee, Waukesha, Brillion, Monroe, Henderson, and Duke Ellington. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 97, 1977-1978

97th SEASON BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA AI//J-/C Director . TRUST BANKING. A symphony in financial planning. Conducted by Boston Safe Deposit and Trust Company Decisions which affect personal financial goals are often best made in concert with a professional advisor. However, some situations require consultation with a number of professionals skilled in different areas of financial management. Real estate advisors . Tax consultants Estate planners . Investment managers To assist people with these needs, our venerable Boston banking institution has developed a new banking concept which integrates all of these professional services into a single program. The program is called trust banking. Orchestrated by Roger Dane, Vice President, 722-7022, for a modest fee. DIRECTORS Hans H. Estin George W. Phillips C. Vincent Vappi Vernon R. Alden Vice Chairman, North Executive Vice President, Vappi & Chairman, Executive American Management President Company, Inc. Committee Corporation George Putnam JepthaH. Wade Nathan H. Garrick, Jr. DvvightL. Allison, Jr. Chairman, Putnam Partner, Choate, Hall Chairman of the Board Vice Chairman of the Management & Stewart Board David C. Crockett Company, Inc. William W.Wolbach Donald Hurley Deputv to the Chairman J. John E. Rogerson Vice Chairman Partner, of the Board of Trustees Goodwin, Partner, Hutchins & of the Board Proctor and to the General & Hoar Wheeler Honorarv Director Director, Massachusetts Robert Mainer Henry E. Russell Sidney R. Rabb General Hospital Senior Vice President, President Chairman, The Stop & The Boston Company, F. Stanton Deland, Jr. Mrs. George L. Sargent Shop Companies, mc. Partner, Sherburne, Inc. Director of Various Powers & Needham William F. Morton Corporarions Director of Various Charles W. -

Painterly Representation in New York: 1945-1975

PAINTERLY REPRESENTATION IN NEW YORK, 1945-1975 by JENNIFER SACHS SAMET A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2010 © 2010 JENNIFER SACHS SAMET All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Dr. Patricia Mainardi Chair of the Examining Committee Date Dr. Patricia Mainardi Acting Executive Officer Dr. Katherine Manthorne Dr. Rose-Carol Washton Long Ms. Martica Sawin Supervision Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract PAINTERLY REPRESENTATION IN NEW YORK, 1945-1975 by JENNIFER SACHS SAMET Advisor: Professor Patricia Mainardi Although the myth persists that figurative painting in New York did not exist after the age of Abstract Expressionism, many artists in fact worked with a painterly, representational vocabulary during this period and throughout the 1960s and 1970s. This dissertation is the first survey of a group of painters working in this mode, all born around the 1920s and living in New York. Several, though not all, were students of Hans Hofmann; most knew one another; some were close friends or colleagues as art teachers. I highlight nine artists: Rosemarie Beck (1923-2003), Leland Bell (1922-1991), Nell Blaine (1922-1996), Robert De Niro (1922-1993), Paul Georges (1923-2002), Albert Kresch (b. 1922), Mercedes Matter (1913-2001), Louisa Matthiasdottir (1917-2000), and Paul Resika (b. 1928). This group of artists has been marginalized in standard art historical surveys and accounts of the period. -

In Plain Sigh

HIDDE in plain sigh .,_ .. ' 1980 Ouachitonial in plain sight 80 Ouachitonian Volume 71 The YOOIAI"t "dorm mom," DennisStarltrides atop a lire enalne in the homeroming parade. Each of the donn mom• rock the tnl~ Stark is the !lead resident of Blake Donn, fondly referred to as the Blake Hilton on Static'• •hirt. 'Ouachita had a glossy image and high pro~ile . But behind these successes, adherence to basic values was the real strength . ' Published by: The Communications Department Ouachita Baptist University Arkadelphia, Arkansas 71923 lt/3 HIDDEN in plain sight Ouachita Baptist University- the name alone significant. "Ouachita," bor little Bible college stuck in the dents accepted at the leading wed from the first indian set mountains but a liberal arts uni medical and dental schools. ACT in the Clark County area, re versity with a serious Christian scores of entering freshmen were tradition and dearly estab emphasis. consistently higher than the na that the university was a It was that commitment to tional average. of Arkansas, not just in Ar- Christian and educational excel Additionally, OBU boasted one lence that provided the founda of the best student foundations tion for everything the university and one of the best yearbooks in family accomplished. Ouachita 'the country. That was pretty good had a glossy image and a very for a school with an enrollment of of wihat the university stood high profile among Arkansas col only 1578 students. leges-that was nice. We kept up All these things were the obvi :.Jniversity," confirmed the with the best of them in sports. -

Download Issue (PDF)

wdmaqart WOMEN SHOOT WOMEN: Films About Women Artists The recent public television series "The Originals: Women in Art" has brought attention to this burgeoning film genre by Carrie Rickey pag e 4 NOTES FROM HOUSTON New York State's artist-delegate to the International Women's Year Convention in Houston, Texas in a personal report on her experiences in politics by Susan S ch w a lb pag e 9 SYLVIA SLEIGH: Portraits of Women in Art Sleigh's recent portrait series acknowledges historical roots as well as the contemporary activism of her subjects by Barbara Cavaliere ......................................................................pag e 12 TENTH STREET REVISITED: Another look at New York’s cooperative galleries of the 1950s WOMEN ARTISTS ON FILM Interviews with women artist/co-op members produce surprising answers to questions about that era by Nancy Ungar page 15 SPECIAL REPORT: W omen’s Caucus for Art/College Art Association 1978 Annual Meetings Com plete coverage of all WCA sessions and activities, plus an exclusive interview with Lee Anne Miller, new WCA president.................................................................................pag e 19 PRIMITIVISM AND WOMEN’S ART Are primitivism and mythology answers to the need for non-male definitions of the feminine? by Lawrence Alloway ......................................................................p a g e 31 SYLVIA SLEIGH GALLERY REVIEWS pa g e 34 REPORTS An Evening with Ten Connecticut Women Artists; WAIT Becomes WCA/Florida Chapter page 42 Cover: Alice Neel, subject of one of the new films about women artists, in her studio. Photo: Gyorgy Beke. WOMANART MAGAZINE Is published quarterly by Womanart Enterprises, 161 Prospect Park West, Brooklyn, New York 11215, (212) 499-3357. -

The Response of African Americans to the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970

‘Black America Cares’: The Response of African Americans to the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970 By James Austin Farquharson B.A, M.A (Research) A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Education and Arts Australian Catholic University 7 November 2019 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material that has been extracted in whole or in part from a thesis that I have submitted towards the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgment in the main text of the thesis. ‘Black America Cares’: The response of African Americans to the Nigerian Civil War, 1967-1970 Abstract Far from having only marginal significance and generating a ‘subdued’ response among African Americans, as some historians have argued, the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970) collided at full velocity with the conflicting discourses and ideas by which black Americans sought to understand their place in the United States and the world in the late 1960s. Black liberal civil rights leaders leapt to offer their service as agents of direct diplomacy during the conflict, seeking to preserve Nigerian unity; grassroots activists from New York to Kansas organised food-drives, concerts and awareness campaigns in support of humanitarian aid for Biafran victims of starvation; while other pro-Biafran black activists warned of links between black ‘genocide’ in Biafra and the US alike. This thesis is the first to recover and analyse at length the extent, complexity and character of such African American responses to the Nigerian Civil War. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 11-9-2006 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (2006). The George-Anne. 2027. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/2027 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Flag football tourney in town Saturday i HIATUS, P.I B Rock show at the Apex I HIATUS, P.IB Hey Hooligans Culture on display at We preview what to look for as the Saturday International Fest. Volume 79 I Number 57 basketball season nears I SPORTS, p.4A NEWS, p. 2A DAILY THE GEORGE THURSDAY, NOVEMBER Q,2006 CENTENNIAL MIDTERM ELECTIONS 190 6-2006 _ Band questioned Democrats' Day G-A ethics with HOUSE POWER musical lashing Democrats had a solid majority (232-203) Wednesday with By Casey Altman several seats still "Sr. staff writer undecided. The Eagles' Fight Song was writ- SENATE ten and performed for the first time by the Georgia Southern College POWER marching band in 1982, the year Democrats seemed that Coach Erk Russell resurrected poised to take control the Eagle football program. of the Senate (51-49) While Russell was preparing the with upset, but Eagles for their first flight, another close, wins in Missouri and Virginia. -

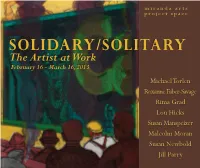

Solidary/Solitary

miranda arts project space Solidary/Solitary The Artist at Work February 16 - March 16, 2013 Michael Torlen Roxanne Faber-Savage Rima Grad Lou Hicks Susan Manspeizer Malcolm Moran Susan Newbold Jill Parry Solidary/Solitary The Artist at Work February 16 - March 16, 2013 Reception and Gallery Talk with Michael Torlen Saturday, February 16 Gallery Talk: 5pm Artists: Michael Torlen, Roxanne Faber-Savage, Rima Grad, Lou Hicks, Susan Manspeizer, Malcolm Moran, Susan Newbold, Jill Parry The short story by Albert Camus, The Artist at Work, tells of an artist’s journey of solitude and solidarity. Solidary/Solitary; The Artist at Work explores the idea of artist critique groups through an exhibition curated from a selection of artists, originally organized by the gallery, that has been meeting for critique and discussion since 2004. This particular group has been led by Michael Torlen, artist and Professor Emeritus at Purchase College, State University of New York. A rich discussion has grown and developed over these years. This dialogue, explored in the gallery talk, is in relation to this show as well as to larger ideas of artists communities. Miranda Arts Project Space is committed to expanding the conversation around local artist-run culture. curated by Patricia Miranda director, miranda arts project space Artist-Run Culture Artist-run culture may be a trendy new term, but it has been an enduring phenomenon in the lives of artists since the medieval guilds and beyond- likely wherever and whenever artists have gathered to work. Artists today practice an interesting map of strategies for living- a complex combination of utopian ideals, pragmatic strategies, hard work and little sleep.