The Evolution of the Jazz Vocal Song: What Comes After the Great American Song Book?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Becca Stevens Singer / Songwriter / Performer Biography

BECCA STEVENS SINGER / SONGWRITER / PERFORMER BIOGRAPHY North Carolina bred, Brooklyn based singer/multi- instrumentalist Becca Stevens is a composer, bandleader, and educator. In her playing, singing, and writing, Stevens has a voice that can only be accurately described as her own. Her original music is hailed worldwide for its its intricate harmonies and rhythms subtly rooted in jazz and Irish Folk and West African music. Boundless in the elements from which she draws her inspiration, Stevens is known for her unique ability to craft exquisite and authentic compositions both for her own band, and for GRAMMY award winning artists who run the gamut of genre from Jacob Collier, to Michael League (Snarky Puppy), and most notably with folk legend David Crosby. Stevens is a member of Crosby’s Lighthouse Band whose album ‘Here If You Listen’ (BMG ‘18), features the distinct songwriting of its four members— Stevens, Crosby, League, and Michelle Willis. Stevens has received copious praise from the likes of The New York Times, was Downbeat Magazine’s 2017 Rising Star Female Vocalist, and was featured on NPR Music’s “Songs We Love”. She has toured the world performing with her band, and collaborating with peers such as Brad Mehldau, Kneebody, Esperanza Spalding, Billy Childs, Ambrose Akinmusire, Vijay Iyer, Taylor Eigsti, José James, Eric Harland, Gerald Clayton, Travis Sullivan’s Björkestra and many others. In 2015, Perfect Animal, the highly anticipated follow up to Weightless (Sunnyside), produced by engineer Scott Solter, was released on Universal Music Classics. Becca’s music is featured on Snarky Puppy’s Family Dinner, Vol. -

Rosemary Lane the Pentangle Magazine

Rosemary Lane the pentangle magazine Issue No 12 Summer 1997 Rosemary Lane Editorial... (thanks, but which season? and we'd Seasonal Greetings! rather have had the mag earlier!) o as the summer turns into autumn here we extensive are these re-issues of the Transatlantic are once more with the latest on Pentangle years - with over 30 tracks on each double CD in Rosemary Lane. In what now seems to be that the juxtaposition of the various musical its characteristic mode of production - i.e. long styles is frequently quite startling and often overdue and much anticipated - thanks for the refreshing in reminding you just how broad the reminders! - we nevertheless have some tasty Pentangle repertoire was in both its collective morsels of Pentangular news and music despite and individual manifestations. More on these the fact that all three current recording projects by in news and reviews. Bert and John and Jacqui remain works in progress - (see, Rosemary Lane is not the only venture that runs foul of the limitations of one human being!). there’s a piece this time round from a young Nonetheless Bert has in fact recorded around 15 admirer of Bert’s who tells how he sounds to the or 16 tracks from which to choose material and in ears of a teenage fan of the likes of Morrissey and the interview on page 11 - Been On The Road So Pulp. And while many may be busy re-cycling Long! - he gives a few clues as to what the tracks Pentangle recordings, Peter Noad writes on how are and some intriguing comments on the feel of Jacqui and band have been throwing themselves the album. -

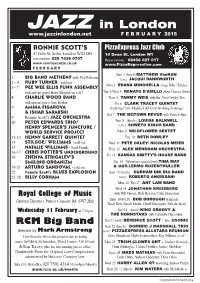

JAZZ in London F E B R U a R Y 2015

JAZZ in London www.jazzinlondon.net F E B R U A R Y 2015 RONNIE SCOTT’S PizzaExpress Jazz Club 47 Frith St. Soho, London W1D 4HT 10 Dean St. London W1 reservations: 020 7439 0747 Reservations: 08456 027 017 www.ronniescotts.co.uk www.PizzaExpresslive.com F E B R U A R Y Sun 1 (lunch) MATTHEW VanKAN with Phil Robson 1 BIG BAND METHENY (eve) JACQUI DANKWORTH 2 - 4 RUBY TURNER - sold out Mon 2 sings Billie Holiday 5 - 7 PEE WEE ELLIS FUNK ASSEMBLY EDANA MINGHELLA with special guest Huey Morgan on 6 & 7 Tue 3/Wed 4 RENATO D’AIELLO plays Horace Silver 8 CHARLIE WOOD BAND Thur 5 TAMMY WEIS with the Tom Cawley Trio with special guest Guy Barker Fri 6 CLARK TRACEY QUINTET 9 AMINA FIGAROVA featuring Chris Maddock & Henry Armburg-Jennings & ISHAR SARABSKI Sat 7 THE MOTOWN REVUE with Patrick Alan 9 Ronnie Scott’s JAZZ ORCHESTRA 10 PETER EDWARDS TRIO/ Sun 8 (lunch) LOUISE BALKWILL (eve) HENRY SPENCER’S JUNCTURE / SOWETO KINCH BAND WORLD SERVICE PROJECT Mon 9 WILDFLOWER SEXTET 11- 13 KENNY GARRETT QUINTET Tue 10 BETH ROWLEY 14 STILGOE/ WILLIAMS - sold out Wed 11 PETE OXLEY/ NICOLAS MEIER 15 - Soul Family NATALIE WILLIAMS Thur 12 ALEX MENDHAM ORCHESTRA 16-17 CHRIS POTTER’S UNDERGROUND Fri 13 18 ZHENYA STRIGALEV’S KANSAS SMITTY’S HOUSE BAND SMILING ORGANIZM Sat 14 Valentine’s special with TINA MAY 19-21 ARTURO SANDOVAL - sold out & GUILLERMO ROZENTHULLER 22 Ronnie Scott’s BLUES EXPLOSION Sun 15 (lunch) DURHAM UNI BIG BAND 23-28 BILLY COBHAM (eve) ROBERTO ANGRISANI Mon 16/ Tue17 ANT LAW BAND Wed 18 JONATHAN KREISBERG Royal College of Music with Will Vinson, Rick Rosato, Colin Stranahan (Britten Theatre) Prince Consort Rd. -

Ronnie Scott's Jazz C

GIVE SOMEONE THE GIFT OF JAZZ THIS CHRISTMAS b u l C 7 z 1 0 z 2 a r J MEMBERSHIP TO e b s ’ m t t e c o e c D / S r e e i GO TO: WWW.RONNIESCOTTS.CO.UK b n OR CALL: 020 74390747 m e n v o Europe’s Premier Jazz Club in the heart of Soho, London o N R Cover artist: Roberto Fonseca (Mon 27th - Wed 29th Nov) Page 36 Page 01 Artists at a Glance Wed 1st - Thurs 2nd: The Yellowjackets N LD OUT Wed 1st: Late Late Show Special - Too Many Zooz SO o Fri 3rd: Jeff Lorber Fusion v Sat 4th: Ben Sidran e m Sun 5th Lunch Jazz: Jitter Kings b Sun 5th: Dean Brown Band e Mon 6th - Tues 7th: Joe Lovano Classic Quartet r Wed 8th: Ronnie Scott’s Gala Charity Night feat. Curtis Stigers + Special Guests Thurs 9th: Marius Neset Quintet Fri 10th - Sat 11th: Manu Dibango & The Soul Makossa Gang Sun 12th Lunch Jazz: Salena Jones “Jazz Doyenne” Sun 12th: Matthew Stevens Preverbal November and December are the busiest times Mon 13th - Tues 14th: Mark Guiliana Jazz Quartet of the year here at the club, although it has to be Wed 15th - Thurs 16th: Becca Stevens Fri 17th - Sat 18th: Mike Stern / Dave Weckl Band feat. Tom Kennedy & Bob Malach UT said there is no time when we seem to slow down. Sun 19th Lunch Jazz: Jivin’ Miss Daisy feat. Liz Fletcher SOLD O November this year brings our Fundraising night Sun 19th: Jazzmeia Horn Sun 19th: Ezra Collective + Kokoroko + Thris Tian (Venue: Islington Assembly Hall) for the Ronnie Scott’s Charitable Foundation on Mon 20th - Tues 21st: Simon Phillips with Protocol IV November 8th featuring the Curtis Stigers Sinatra Wed 22nd: An Evening of Gershwin feat. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Windward Passenger

MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE BURRELL WINDWARD PASSENGER PHEEROAN NICKI DOM HASAAN akLAFF PARROTT SALVADOR IBN ALI Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : PHEEROAN aklaff 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : nicki parrott 7 by jim motavalli General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : dave burrell 8 by john sharpe Advertising: [email protected] Encore : dom salvador by laurel gross Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : HASAAN IBN ALI 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : space time by ken dryden US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIVAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD ReviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 44 Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Kevin Canfield, Marco Cangiano, Pierre Crépon George Grella, Laurel Gross, Jim Motavalli, Greg Packham, Eric Wendell Contributing Photographers In jazz parlance, the “rhythm section” is shorthand for piano, bass and drums. -

Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM Table of Contents

MUsic Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM table of contents Sheet Music ....................................................................................................... 3 Jazz Instruction ....................................................................................... 48 Fake Books........................................................................................................ 4 A New Tune a Day Series ......................................................................... 48 Personality Folios .............................................................................................. 5 Orchestra Musician’s CD-ROM Library .................................................... 50 Songwriter Collections ..................................................................................... 16 Music Minus One .................................................................................... 50 Mixed Folios .................................................................................................... 17 Strings..................................................................................................... 52 Best Ever Series ...................................................................................... 22 Violin Play-Along ..................................................................................... 52 Big Books of Music ................................................................................. 22 Woodwinds ............................................................................................ -

Music Events at Queen's

MUSIC EVENTS AT QUEEN’S Autumn / Winter 2017 www.qub.ac.uk/ael/events Map Contact us 28 September 13.10 Concert Sonic Lab 5 T. 028 9097 5337 Roy Carroll University Street W. www.qub.ac.uk/ael/events Berlin-based Roy Carroll ‘s work encompasses improvisation, Fitzwilliam Street @creativeartsqub composition, collaborations with choreographers and University Square @creativeartsqub Botanic Avenue experimental research, with porous borders in between. His 4 1 works use multiple objects and materials interacting through amplification and signal processing to create multi-layered University Road forms, orbiting around the listener. We’re delighted to Key welcome him back to SARC. 3 Seminar Free, but tickets must be booked in advance via Eventbrite. This concert is co-promoted by Moving On Music. Tickets are available via Concert their website at www.movingonmusic.com Stranmillis Road 29 September 10.30 1 Old McMordie Hall (OMcMH) Seminar Sonic Lab Malone Road 2 Sonic Lab (SARC) 3 Whitla Hall Note: All concert events are free except where stated. Roy Carroll However, ALL SARC event tickets must be booked Cloreen Park2 4 Harty Room in advance via Eventbrite: tickets are available at the Roy presents a seminar/workshop as a follow-up to the previous day’s 5 Crescent Arts Centre MovingOnMusic website. www.movingonmusic.com Sonic Lab concert 3 4 October 13.00 5 October 13.10 8 October 20.00 Seminar Old McMordie Hall Concert Harty Room Concert Sonic Lab Sweet Shop or China Shop? Schubert’s Octet D803 FIX17 — VocalSuite: Ulster Orchestra Soloists, Negotiating a proliferation directed by Ioana Petcu-Colan Cleveland Watkiss of compositional paths In a co-promotion with Catalyst Arts as part of We are thrilled to open our 2017–18 season in the Dr Ian Wilson FIX 17 live art and performance festival, virtuoso Harty Room with a rare performance of one of the vocalist, actor and composer Cleveland Watkiss giants of European Chamber Music, Schubert’s presents VocalSuite. -

Rachel Agan Graduate Recital

Rachel Agan Acknowledgements percussion • I would like to thank my instructor and advisor, Dr. Brian Pfeifer, for all the knowledge and insight he’s passed down over the years. Graduate Recital Thank you for always pushing me to think critically in performance, education, and life. • Thank you to my lovely guest artist and human ray of sunshine, Mandy Moreno. Putting together our jazz set for this recital was easily my favorite part of the whole process! Collaborating with you was fun, easy, and educational. • I would like to thank my family and friends for providing a strong featuring support system as I pursue a career in music. Thank you for always pushing me to do more than I believe is possible. Mandy Moreno • Thank you to all the hardworking staff and faculty in the UND voice Music Department. Fostering an educational environment that meets expectedly high standards is a challenge in the middle of a pandemic, but you’re all succeeding. I see you and appreciate you. • Thank you to Dr. Cory Driscoll for coordinating the recording and live-streaming of this recital. • Thank you to every music teacher I’ve had in the past who has influenced the musician I am today. • Thank YOU for tuning in! Josephine Campbell Recital Hall This recital is in partial fulfillment of a Sunday, April 18th, 2021 Masters of Music: Percussion Performance. 2:00 pm UND.edu/music 701.777.2644 UND.edu/music 701.777.2644 Program Program Notes Rebonds Iannis Xenakis Rebonds (1987-9) Iannis Xenakis A (1922-2001) Xenakis was a Greek-French composer active in the late-20th century in Paris. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Prospectus 19/ 20 Trinity Laban Conservatoire Of

PROSPECTUS 19/20 TRINITY LABAN CONSERVATOIRE OF MUSIC & DANCE CONTENTS 3 Principal’s Welcome 56 Music 4 Why You Should #ChooseTL 58 Performance Opportunities 6 How to #ExperienceTL 60 Music Programmes FORWARD 8 Our Home in London 60 Undergraduate Programmes 10 Student Life 62 Postgraduate Programmes 64 Professional Development Programmes 12 Accommodation 13 Students' Union 66 Academic Studies 14 Student Services 70 Music Departments 16 International Community 70 Music Education THINKING 18 Global Links 72 Composition 74 Jazz Trinity Laban is a unique partnership 20 Professional Partnerships 76 Keyboard in music and dance that is redefining 22 CoLab 78 Strings the conservatoire of the 21st century. 24 Research 80 Vocal Studies 82 Wind, Brass & Percussion Our mission: to advance the art forms 28 Dance 86 Careers in Music of music and dance by bringing together 30 Dance Staff 88 Music Alumni artists to train, collaborate, research WELCOME 32 Performance Environment and perform in an environment of 98 Musical Theatre 34 Transitions Dance Company creative and technical excellence. 36 Dance Programmes 106 How to Apply 36 Undergraduate Programmes 108 Auditions 40 Masters Programmes 44 Diploma Programmes 110 Fees, Funding & Scholarships 46 Careers in Dance 111 Admissions FAQs 48 Dance Alumni 114 How to Find Us Trinity Laban, the UK’s first conservatoire of music and dance, was formed in 2005 by the coming together of Trinity College of Music and Laban, two leading centres of music and dance. Building on our distinctive heritage – and our extensive experience in providing innovative education and training in the performing arts – we embrace the new, the experimental and the unexpected. -

Goodbye Pork Pie Hat Words & Music: Joni Mitchell & Charles Mingus

Goodbye Pork Pie Hat Words & Music: Joni Mitchell & Charles Mingus Joni set words to many of Mingus' jazz tunes on the 1979 album Mingus. Luckily, Charles Mingus was able to hear the results of the collaboration before his death that same year. If you don't know Mingus' work, go discover it. Works like "Fables of Faubus", "Better Git It In Your Soul" & "Slop" are sublime. The noted Jeff Beck cover of this tune earned the rare honor of a complete transcription in the November 2004 issue of Guitar Player. Chords are courtesy of Vivek Ayer. It is hard to map them to the words exactly, due to the free nature of the singing, but use Vivek's map & notes below. "This is a blues song with cool/weird changes written by Charles Mingus famously covered Beck, John Mclaughlin and Joni Mitchell. It's a 12 bar blues (can be read as 3 sections of 4 bars each) These chords can be played as a chord melody arrangement: | Ebm* B13| EM7+11 A7b5 | C#m9 B9| C#9 Eb7 | | Abm7 B13| EM7+11 Bb7#9#5 | C7b5 F7| B7 EM7| | A13 Ab7 | Bb7 C#7** | Ebm B7 | E A7 || * If you're not playing the melody I'd recommend Eb7#9 ** Some versions just play B9 for 2 bars here Eb7#9[Ebm] B13 EM7+11 A7b5 When Charlie speaks of Lester, you know someone great has gone. C#m9 B9 C#9 Eb7 The sweetest, swinging music man had a Porky Pig hat on. Abm7 B13 EM7+11 Bb7#9#5 A bright star in a dark age when the bandstands had a thousand ways C7b5 F7 B7 EM7 A13 Ab7 Of refusing a black man admission, black musician.