Simplicity and Survival: Vernacular Response in Newfoundland Architecture by Shane O'dea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author' s Permission) p CLASS ACTS: CULINARY TOURISM IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR by Holly Jeannine Everett A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Folklore Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2005 St. John's Newfoundland ii Class Acts: Culinary Tourism in Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract This thesis, building on the conceptual framework outlined by folklorist Lucy Long, examines culinary tourism in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. The data upon which the analysis rests was collected through participant observation as well as qualitative interviews and surveys. The first chapter consists of a brief overview of traditional foodways in Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as a summary of the current state of the tourism industry. As well, the methodology which underpins the study is presented. Chapter two examines the historical origins of culinary tourism and the development of the idea in the Canadian context. The chapter ends with a description of Newfoundland and Labrador's current culinary marketing campaign, "A Taste of Newfoundland and Labrador." With particular attention to folklore scholarship, the course of academic attention to foodways and tourism, both separately and in tandem, is documented in chapter three. The second part of the thesis consists of three case studies. Chapter four examines the uses of seal flipper pie in hegemonic discourse about the province and its culture. Fried foods, specifically fried fish, potatoes and cod tongues, provide the starting point for a discussion of changing attitudes toward food, health and the obligations of citizenry in chapter five. -

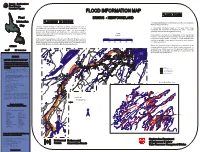

FLOOD INFORMATION MAP FLOOD ZONES Flood BRIGUS - NEWFOUNDLAND

Canada - Newfoundland Flood Damage Reduction Program FLOOD INFORMATION MAP FLOOD ZONES Flood BRIGUS - NEWFOUNDLAND Information FLOODING IN BRIGUS A "designated floodway" (1:20 flood zone) is the area subject to the most frequent flooding. Map Flooding causes damage to personal property, disrupts the lives of individuals and communities, and can be a threat to life itself. Continuing Beth A "designated floodway fringe" (1:100 year flood zone) development of flood plain increases these risks. The governments of une' constitutes the remainder of the flood risk area. This area Canada and Newfoundland and Labrador are sometimes asked to s Po generally receives less damage from flooding. compensate property owners for damage by floods or are expected to find Scale nd solutions to these problems. (metres) No building or structure should be erected in the "designated floodway" since extensive damage may result from deeper and While most of the past flood events on Lamb's Brook in Brigus have been more swiftly flowing waters. However, it is often desirable, and caused by a combination of high flows and ice jams at hydraulic structures may be acceptable, to use land in this area for agricultural or floods can occur due to heavy rainfall and snow melt. This was the case in 0 200 400 600 800 1000 recreational purposes. January 1995 when the Conception Bay Highway was flooded. Within the "floodway fringe" a building, or an alteration to an BRIGUS existing building, should receive flood proofing measures. A variety of these may be used, e.g.. the placing of a dyke around Canada Newfoundland the building, the construction of a building on raised land, or by Brigus the special design of a building. -

ARCHIVES and SPECIAL COLLECTIONS QUEEN ELIZABETH II LIBRARY MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY, ST

ARCHIVES and SPECIAL COLLECTIONS QUEEN ELIZABETH II LIBRARY MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY, ST. JOHN'S, NL Mary Schwall Photograph Collection COLL-206 Website: Archives and Special Collections Author: Bert Riggs Date: 1996 Scope and Content: This collection consists of 135 photographs taken by Mary Schwall or her companions while on excursions to Newfoundland during 1913 and 1915. They are a pictorial record of a journey by ship from Nova Scotia to Newfoundland, a train trip from Channel to St. John's, and a trip from St. John's north around the coast to St. Anthony, across the Strait of Belle Isle to Labrador and down the west coast of the Great Northern Peninsula. There is evidence that the photographs were taken during two trips to Newfoundland, as two photographs have the date 1913 on the back with the caption, while another has the date 1915. The photographs provide visual documentation of Mary Schwall's vacations, but they also provide valuable information on Newfoundland communities during the early years of the twentieth century. Vernacular architecture historians have attested to the fact that several of the photographs show buildings only previously known through oral accounts. As well there is visual documentation of people, especially children, which can provide information on lifestyle, dress, nutrition, disease, and a host of other subjects.In addition, there are 56 postcards with images covering much the same geographical area as the photographs, leading one to believe that they were purchased in larger communities during stopovers, or possibly in St. John's. Most of the postcards were produced for the St. -

Pennecon-Talk-SPRING2017.Pdf

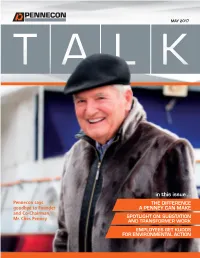

MAY 2017 in this issue ... Pennecon says THE DIFFERENCE goodbye to Founder A PENNEY CAN MAKE and Co-Chairman, SPOTLIGHT ON: SUBSTATION Mr. Ches Penney AND TRANSFORMER WORK EMPLOYEES GET KUDOS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL ACTION CONTINUED FROM COVER WE WILL NEVER FORGET THE DIFFERENCE A PENNEY CAN MAKE A Message from the Executive Chairman On January 26th, 2017, we said goodbye to Pennecon’s Founder and Co-Chairman, Ches Penney, who passed away peacefully at the age of 84, surrounded by his loving family. He lived a long and full life, and we are thankful to have had the opportunity to work with him, learn from him, and laugh with him. The Skipper, as many of us affectionately called him, was a visionary leader known for his transparency, his grit, his charity, and his humility. He has been recognized on a personal level for his business success and philanthropy. His commitment to the people and the province of Newfoundland and Labrador will be felt for generations. Ches credited his success to his partners and employees. He often illustrated his wisdom on succession planning by saying, “I set up my businesses so that when I’m gone, it will make no difference.” Of course, we all know it makes a great deal of difference. Indeed I, like so many of the people who worked with him, will deeply miss his passion, his antics and his presence. However, I can agree with confidence that Pennecon will continue to grow and thrive – and that is, in part, because of Ches’s knack for selecting capable, hardworking people and empowering them to succeed. -

Exerpt from Joey Smallwood

This painting entitled We Filled ‘Em To The Gunnells by Sheila Hollander shows what life possibly may have been like in XXX circa XXX. Fig. 3.4 499 TOPIC 6.1 Did Newfoundland make the right choice when it joined Canada in 1949? If Newfoundland had remained on its own as a country, what might be different today? 6.1 Smallwood campaigning for Confederation 6.2 Steps in the Confederation process, 1946-1949 THE CONFEDERATION PROCESS Sept. 11, 1946: The April 24, 1947: June 19, 1947: Jan. 28, 1948: March 11, 1948: Overriding National Convention The London The Ottawa The National Convention the National Convention’s opens. delegation departs. delegation departs. decides not to put decision, Britain announces confederation as an option that confederation will be on on the referendum ballot. the ballot after all. 1946 1947 1948 1949 June 3, 1948: July 22, 1948: Dec. 11, 1948: Terms March 31, 1949: April 1, 1949: Joseph R. First referendum Second referendum of Union are signed Newfoundland Smallwood and his cabinet is held. is held. between Canada officially becomes are sworn in as an interim and Newfoundland. the tenth province government until the first of Canada. provincial election can be held. 500 The Referendum Campaigns: The Confederates Despite the decision by the National Convention on The Confederate Association was well-funded, well- January 28, 1948 not to include Confederation on the organized, and had an effective island-wide network. referendum ballot, the British government announced It focused on the material advantages of confederation, on March 11 that it would be placed on the ballot as especially in terms of improved social services – family an option after all. -

National Librarian Visits the Atlantic Region

• e l The Atlantic Provinces Library Association Volume 63, Number 4 ISSN 0001-2203 January / February 2000 National Librarian Visits the Atlantic Region The day's library issues forum took place, between Left to right: Jocelyne Thompson, New Brunswick Provincial Librarian; Roch Carrier, National Librarian; John Teshcy, 12:00 and 2:00 at the Lord Dalhousie Room, on University Librarian, UNB; Sara Lochhead, University Librarian, Dalhousie University campus, hosted hy the Dalhousie Mount Allison University School of Information Studies, and moderated by the schools director Bertrum MacDonald. The forum was NOVA SCOTIA: Tuesday November 30,1999 well attended by over 60 people. Fourteen speakers gave For Roch Carrier's visit, arrangements in Halifax brief presentations. They represented Nova Scotia were ably coordinated by the staff of the Nova Scotia library associations and agencies and a wide range of Provincial Library, with assistance and support from a library sectors, including school, university, government number of individuals and organizations. Roch Carrier and law libraries, as well as library students, public and began the day with a breakfast with staff of the Nova other special libraries. A wide range of library initiatives Scotia Provincial Library. He then toured the Terrence and pressing issues were discussed. Themes which came Bay Elementary School Library. Next was a visit to the up repeatedly, were the need for resource sharing ven library of the John A. MacDonald High school, and a tures, and centralized leadership to find innovative ways meeting with students there. Then came a visit to the to address the growing resource shortages our institu Halifax Regional Public Library, Spryfield Branch. -

Labrador; These Will Be Done During the Summer

Fisheries Peches I and Oceans et Oceans 0 NEWFOUNDLAND REGION ((ANNUAL REPORT 1985-86 Canada ) ceare SMALL CRAFT HARBOURS BRANCH Y.'• ;'''' . ./ DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES AND OCEANS NEWFOUNDLAND REGION . 0 4.s.'73 ' ANNUAL REPORT - 1985/86 R edlioft TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Overview and Summary 1 2. Small Craft Harbours Branch National Planning Framework 3 3. Long Range Planning: Nfld. Region 8 4. Project Evaluation 10 5. Harbour Maintenance and Development Programs 11 6. Harbour Operations 16 7. Budget Utilization (Summary) 1985/86 17 APPENDICES 1. Photos 2. Harbour Classification 3. Minimum Services Offered 4. Condition Rating Scale 5. Examples of Project Type 6. Project Evaluation 7. Regular Program Projects 1985/86 8. Joint SCH-Job Creation Projects 1984/85/86 9. Joint SCH-Job Creation Projects 1985/86/87 10. Dredging Projects Utilizing DPW Plant 11. Advance Planning 12. Property Acquisition Underway 1 OVERVIEW AND SUMMARY Since the establishment of Small Craft Harbours Branch of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans in 1973, the Branch has been providing facilities such as breakwaters, wharves, slipways, gear storage, shore protection, floats and the dredging of channels and basins, in fishing and recreational harbours within the Newfoundland Region. This third annual report produced by Small Craft Harbours Branch, Newfoundland Region, covers the major activities of the Branch for the fiscal year 1985/86. During the fiscal year continuing efforts were made towards planning of the Small Craft Harbours Program to better define and priorize projects, and to maximize the socio-economic benefits to the commercial fishing industry. This has been an on-going process and additional emphasis was placed on this activity over the past three years. -

“I'd Rather Have a Prayer Book Than a Shirt”: the Printed Word Among

Document generated on 09/28/2021 12:24 p.m. Newfoundland and Labrador Studies “I’d rather have a Prayer Book than a shirt” The Printed Word among Methodists and Anglicans in Nineteenth-Century Outport Newfoundland and Labrador Calvin Hollett Volume 32, Number 2, Fall 2017 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/nflds32_2art02 See table of contents Publisher(s) Faculty of Arts, Memorial University ISSN 1719-1726 (print) 1715-1430 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Hollett, C. (2017). “I’d rather have a Prayer Book than a shirt”: The Printed Word among Methodists and Anglicans in Nineteenth-Century Outport Newfoundland and Labrador. Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, 32(2), 315–343. All rights reserved © Memorial University, 2014 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ “I’d rather have a Prayer Book than a shirt”: The Printed Word among Methodists and Anglicans in Nineteenth-Century Outport Newfoundland and Labrador Calvin Hollett Charles Taylor, in A Secular Age, concludes that the Reformation and the movements leading up to it resulted in an “excarnation” of spirituality. The pre-Reformation Lollards, for instance, “disembod- ied” worship by making it non-visual and non-physical, getting rid of such religious phenomena as relics, saints, crawling to the cross, shrines, and processions. -

Unaudited Supplementary Supplier Lists Supplémentaires Non Vérifiées

Listes de fournisseurs Unaudited Supplementary Supplier Lists supplémentaires non vérifiées The Office of the Comptroller publishes the following Le Bureau du contrôleur publie les listes supplémentaires supplementary lists: suivantes: 1. Employee salaries including Ministerial 1. Traitements des employés, y compris la remuneration, retirement allowance / severance rémunération des ministres, les allocations de payments, travel and other expenses for each retraite / indemnités de cessation d’emploi, les government department. frais de déplacement et autres dépenses pour 2. Employee salaries and retirement allowance / chacun des ministères. severance payments for government Crown 2. Traitements des employés et allocations de Corporations, and other government organizations. retraite / indemnités de cessation d’emploi des 3. Payments attributed to medical practitioners. sociétés de la Couronne et autres organismes 4. Combined supplier & grant payments and gouvernementaux. payments through purchase cards, including 3. Paiements attribués aux médecins. payments made by all departments and some 4. Paiements aux fournisseurs et subventions government organizations. combinés et paiements au titre des cartes d’achat, 5. Supplier & grant payments, loan disbursements and y compris les paiements effectués par tous les payments through purchase cards for each ministères et par certains organismes department. gouvernementaux. 5. Paiements aux fournisseurs et paiements des subventions, versements de prêts et paiements au titre des cartes d'achat pour chacun des ministères. The supplier lists (4. and 5.) are located below. Supplier, Les listes de fournisseurs (4. et 5.) sont affichées ci- grant, loans and purchase card payment information is for dessous. L’information sur les paiements versés aux the fiscal year ending March 31, 2019. fournisseurs, les paiements des subventions, les versements de prêts et les paiements au titre des cartes d'achat est présentée pour l’exercice terminé le 31 mars 2019. -

Newfoundland and Labrador Branch List

COMMAND 10 BR 009 Water St Harbour Grace, NL A0A 2M0 St John’s SPANIARDS BAY Phone: 709-596-3185 NEWFOUNDLAND/LABRA CPL M BRAZIL DOR COMMAND Po Box 292 BR 016 930 The Boulevard Spaniards Bay, NL A0A 3X0 St John’s , NL A1C 5X3 Phone: 709-786-3671 CATALINA Phone: 709-753-6666 / 709- CATALINA 753-6290 BR 010 Po Box 89 Branch Website Email Catalina, NL A0C 1J0 PORTUGAL COVE-ST Phone: 709-469-3176 BR 001 PHILLIPS PORTUGAL COVE ST. JOHN'S BR 017 ST JOHNS 5 Legion Rd ST ANTHONY Portugal Cove-st Phillips, ST ANTHONY 57-59 Blackmarsh Rd NL A1M 2R5 St. John's, NL A1E 1S6 Phone: 709-895-6521 Po Box 594 Phone: 709-579-8281 St Anthony, NL A0K 4S0 Phone: 709-454-2340 BR 011 BR 003 PORT AUX BASQUES DEER LAKE CHANNEL BR 018 DEER LAKE BELL ISLAND 3 Read St BELL ISLAND 33 Upper Nicholsville Rd Port Aux Basques, NL A0M Deer Lake, NL A8A 2G1 1C0 18 Quigley's Line Phone: 709-635-2177 Phone: 709-695-3981 Bell Island, NL A0A 4H0 Phone: 709-488-2072 BR 005 BR 012 BOTWOOD GRAND FALLS- BR 021 BOTWOOD WINDSOR TWILLINGATE 7 Circular Rd GRAND FALLS TWILLINGATE Botwood, NL A0H 1E0 Po Box 310 Phone: 709-257-2209 Po Box 152 Stn Main Grand Falls-windsor, NL A2A Twillingate, NL A0G 4M0 2J4 Phone: 709-884-5245 BR 007 Phone: 709-489-6560 BONAVISTA BR 022 BONAVISTA BR 013 UPPER ISLAND Po Box 398 CORNER BROOK COVE Bonavista, NL A0C 1B0 CORNER BROOK UPPER ISLAND COVE Phone: 709-468-7376 7 West St Po Box 129 Corner Brook, NL A2H 2Y6 Upper Island Cove, NL A0A BR 008 Phone: 709-634-2040 4E0 GANDER Phone: 709-589-2320 GANDER BR 015 193 Elizabeth Dr HARBOUR GRACE BR 023 Gander, -

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | 0 | P | Q-R | S | T | U-V | W | X-Y-Z A Abraham's Cove Adams Cove, Conception Bay Adeytown, Trinity Bay Admiral's Beach Admiral's Cove see Port Kirwan Aguathuna Alexander Bay Allan’s Island Amherst Cove Anchor Point Anderson’s Cove Angel's Cove Antelope Tickle, Labrador Appleton Aquaforte Argentia Arnold's Cove Aspen, Random Island Aspen Cove, Notre Dame Bay Aspey Brook, Random Island Atlantic Provinces Avalon Peninsula Avalon Wilderness Reserve see Wilderness Areas - Avalon Wilderness Reserve Avondale B (top) Baccalieu see V.F. Wilderness Areas - Baccalieu Island Bacon Cove Badger Badger's Quay Baie Verte Baie Verte Peninsula Baine Harbour Bar Haven Barachois Brook Bareneed Barr'd Harbour, Northern Peninsula Barr'd Islands Barrow Harbour Bartlett's Harbour Barton, Trinity Bay Battle Harbour Bauline Bauline East (Southern Shore) Bay Bulls Bay d'Espoir Bay de Verde Bay de Verde Peninsula Bay du Nord see V.F. Wilderness Areas Bay L'Argent Bay of Exploits Bay of Islands Bay Roberts Bay St. George Bayside see Twillingate Baytona The Beaches Beachside Beau Bois Beaumont, Long Island Beaumont Hamel, France Beaver Cove, Gander Bay Beckford, St. Mary's Bay Beer Cove, Great Northern Peninsula Bell Island (to end of 1989) (1990-1995) (1996-1999) (2000-2009) (2010- ) Bellburn's Belle Isle Belleoram Bellevue Benoit's Cove Benoit’s Siding Benton Bett’s Cove, Notre Dame Bay Bide Arm Big Barasway (Cape Shore) Big Barasway (near Burgeo) see -

37131055405286D.Pdf

THE NEWFOUNDLAND FOR nIE YEAR OF OUR LORD IS61, (BEING THE FIRST AFTER BISSEXTILE, OR LEAP YEAR, AND THE LATTER PART OF THE TWENTY -FOURTH AND THE BEGINNING OF THE TWENTY-FIFTH YEAR OF THE REIGN OF HER MAJESTY QUEEN VICTORIA) CONTAINING ASTRONOMICAL, STATISTICAL, COlVIMERCIAL, LOCAL AND DERIVED FROM THE MOST AUTHENTIC SOURCES. COMPILED, PRINTED AND PUIlLISIIEDBY JOSEPH WOODS . • ST. JOHN'S, NEWFOUNDLAND. MDCCCLX. ASTRONOMICAL PHENOMENA. ECLIPSES, 1861. There will be Four Eclipses this year; three of the SUN and one of the MOON; two only of which are visible in this Island, namely, one of the Sun and one of the Moon. I.-An annular Eclipse of the Sun, January 10, invisible in New foundland. n.-An annu7!ttr Eclipse of the Sun, July 7, invisible in New foundland. These two Solar Eclipses are visible in the North and South Pacific Oceans and in the Indian and Great Southern Oceans. IlL-A pa1'tial Eclipse of the Moon, December 17, visible in Newfoundland :- h. m. First contact with Penumbra (Dec.17) 212m.) First contact with Shadow 355m.} M r Middle. of Eclipse' 4 46m ean Im8 Last contact with Shadow 5 37m: St. John's. Last contact with Penumbra 7 20m. Magnitude of Eclipse (1\'Ioon's diameter=l) 0.185 IV.-A Total Eclipse oj the Sun, December 31, visible as a partial one in Newfoundland. This eclipse will commence on the Earth generally near the south ern part of the Isthmus of Darien, on the 31st December at sun-rise, and after traversing the more northern portions of the American Con tinent, passing rapidly oyer the Atlantic Ocean, visiting Newfound land, Greenland, the British Islands, &c., will terminate on the earth generally in Africa, at longitude 12 0 38 E., near the shores of lhe Mediterranean Sea, at Bun-set .