Patricia Grimshaw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Women, Past and Present

Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Edited by Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein and Mary Tomsic Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Diversity in leadership : Australian women, past and present / Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein, Mary Tomsic, editors. ISBN: 9781925021707 (paperback) 9781925021714 (ebook) Subjects: Leadership in women--Australia. Women--Political activity--Australia. Businesswomen--Australia. Women--Social conditions--Australia Other Authors/Contributors: Damousi, Joy, 1961- editor. Rubenstein, Kim, editor. Tomsic, Mary, editor. Dewey Number: 305.420994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Introduction . 1 Part I. Feminist perspectives and leadership 1 . A feminist case for leadership . 17 Amanda Sinclair Part II. Indigenous women’s leadership 2 . Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts . 39 Gwenda Baker, Joanne Garŋgulkpuy and Kathy Guthadjaka 3 . Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal rights . 53 Rachel Standfield, Ray Peckham and John Nolan Part III. Local and global politics 4 . Women’s International leadership . 71 Marilyn Lake 5 . The big stage: Australian women leading global change . 91 Susan Harris Rimmer 6 . ‘All our strength, all our kindness and our love’: Bertha McNamara, bookseller, socialist, feminist and parliamentary aspirant . -

Patricia Grimshaw

Patricia Grimshaw 100 YEARS OF WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE 1908-2008 Reflection and Celebration Patricia Grimshaw Limited edition handmade publication 2007 Printed and Handbound RMIT University Students from School of Architecture and Design & School of Global Studies,Social Science and Planning Lecturer/Project Manager: Fern Smith Facilitation: Liam Fennessy and Soumitri Varadarajan Project Partners: Women’s Electoral Lobby and League of Women Voters Victoria Adjunct Professor Judith Smart background material on women’s suffrage in Victoria Shawn Callahan of anecdote for opening question techniques Meg Minos for background material on bookbinding Jackie Ralph for transcribing Interviewee: Patricia Grimshaw Interviewed by: Diana White and Sarah Costanzo Interview of Patricia Grimshaw edited by Diana White Copyright: 2007 Patricia Grimshaw I would like to dedicate this to all women fighting for equality Sarah Costanzo Introduction The 24th of November 1908 marks the day when the Legislative Council passed a suffrage bill enabling women for the fi rst time to vote in state elections of Victoria, Australia. For the centenary celebration Liam Fennessy and Sou- mitri Varadarajan, RMIT Industrial Design Program, Kerry Lovering Women’s Electoral Lobby, Sheila Byard Victoria League of Women Voters Victoria and artist Fern Smith worked in partnership; facilitating RMIT students to produce handmade limited edition books of twelve signifi cant women in Victoria. Four students Emma Brelsford, Sarah Costanzo, Cara Jeffery and Diana White conducted twelve two hour interviews with Gracia Baylor, Elleni Bereded-Samuel, Ellen Chandler, Angela Clarke, Ursula Dutkiewicz, Beatrice Faust, Pat Goble, Professor Patricia Grimshaw, Mary Owen, Marian Quartly, Associate Professor Jenny Strauss and Eleanor Sumner. The students had never interviewed, edited nor produced handmade books it is a fantastic achievement with in a twelve-week semester. -

11. Academic Women and Research Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia

11. Academic women and research leadership in twentieth-century Australia Patricia Grimshaw1 and Rosemary Francis2 While the focus of analysis of leadership in tertiary institutions is most commonly the capacities of the most senior academic administrators, many academics at less elevated levels in the hierarchy also can exert major influence in their disciplinary areas that has significant impact nationally and internationally. This chapter offers an insight into Australian women’s leadership in the academic profession in the twentieth century through the careers of outstanding scholars who from the mid 1950s were elected fellows of the Australian learned academies. Women faced considerable barriers to employment in universities before the expansion of secondary and tertiary education in the postwar years increased their opportunities to gain academic positions and advance the cutting edges of their disciplines. Yet, starting in 1956, when the first woman was elected to a learned academy, talented women were singled out as research leaders through this peer evaluation of their importance. With the social changes in gender expectations that the women’s movement inspired and the Australian Labor Party’s affirmative action policies of the 1980s, the number of female senior scholars who reached this standing increased markedly—noticeable especially in the humanities and social sciences. First, this chapter considers the careers of the first group of academicians who were elected to the four academies from 1956 to 1976; second, it traces the election of women from the late 1970s to the end of the century, including a few scholars who became leaders of the academies themselves. The story of academic women and research leadership is overall one of progressive change, but also indicates that gender equity has yet to be attained in the academic profession or, consequently, in the learned academies. -

Creating White Australia

Creating White Australia Edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Published 2009 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Fisher Library, University of Sydney www.sup.usyd.edu.au © Individual authors 2009 © Sydney University Press 2009 Reproduction and communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library University of Sydney NSW Australia 2006 Email: [email protected] National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Creating white Australia / edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky. ISBN: 9781920899424 (pbk.) Subjects: White Australia policy. Racism--Australia. Australia--Emigration and immigration--History. Australia--Race relations--History. Other Authors/Contributors: Carey, Jane, 1972- McLisky, Claire. Dewey Number: 305.80094 Cover design by Evan Shapiro, University Publishing Service, The University of Sydney Printed in Australia Contents Contributors ......................................................................................... v Introduction Creating White Australia: new perspectives on race, whiteness and history ............................................................................................ ix Jane Carey & Claire McLisky Part 1: Global -

Biographies and Autobiographies of Historians, Edited by Doug Munro and John G

11 Country and Kin Calling? Keith Hancock, the National Dictionary Collaboration, and the Promotion of Life Writing in Australia1 Melanie Nolan Australian historians and ego-histoire In his international comparison of history, historians and autobiography in 2005, Jeremy D. Popkin concluded that Australian historians were early to, and enthusiastic about, the ego-histoire movement or the ‘setting down [of] one’s own story’. Australians anticipated Pierre Nora’s collection of essays, Essais d’ego-histoire, which was published in 1987.2 They had already founded ‘a series of autobiographical lectures in 1984’, which resulted in a number of publications, and Australian historians’ memoirs thereafter appeared at a rate of more than one a year.3 When he considered Australian 1 I thank Ann Curthoys and the editors for their comments on an earlier draft. 2 Pierre Nora ed., Essais d’ego-histoire (Paris: Gallimard, 1987), 7. 3 Jeremy D. Popkin, History, Historians, & Autobiography (Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 74. In ‘Ego-histoire Down Under: Australian Historian-Autobiographers’, Australian Historical Studies, 38:129 (2007), 110, doi.org/10.1080/10314610708601234, Popkin dates the Australian memoir bulge from 1982 when collective projects including ‘a volume of professional women’s narratives, The Half-Open Door, which appeared in 1982, and the four volumes of essays starting with the Victorian History Institute’s 1984 forum in which R.M. Crawford, Manning Clark and Geoffrey Blainey participated’. Patricia Grimshaw and Lynne -

Bibliography

Bibliography Archival material Australian Dictionary of Biography Files, Australian National University Archives, Canberra Correspondence to Professor Pike from John Kirkland Wilson Pike, 7 December 1965; Eaves Walton & Stewart, Legal & Historical Research papers, in ‘Katherine Kirkland Biographical File’. ‘David Cannon McConnel Biographical File’. National Library of Australia Index to Passengers to Sydney 1838–1842, Habart Samuel – Justus John, Archives Authority of New South Wales, AO Reel 4; Immigration Agents’ Immigration Lists, April 1838–November 1841:Assisted Immigration, NLA mfm N229, Archives Authority of NSW, Reel No. 2134. Flinders, M 1814, Chart of Terra Australis, Sheet III, East coast [cartographic material], G and W Nicol, London. Nathan F. Spielvogel, ‘When White Men First Looked on Ballarat’, NLA MS 3776. State Records Authority of New South Wales Reports of John Baxter, Joseph Corralis, Lieutenant Otter, Captain Foster Fyans and John Graham, SZ976, COD 183. State Library of New South Wales Martens, Conrad, ‘Bulimba on the Brisbane River, D. C. McConnel Esq., Nov. 21, 1851’, Pencil 19 x 29.5 cm (ML PXC972, f.3). ‘Scott family: mainly studio portraits of the Scott and Townsend families, ca. 1864–1886’, SLNSW, Sydney, PXB 276. 161 In the Eye of the Beholder State Library of Queensland, John Oxley Library, Brisbane McConnel, J C I 1963, ‘The Lives of Frederic and John [sic] Anne McConnel’, McConnel Family Papers, microform no. 755399. State Library of South Australia ‘Letter from George Gawler to Henry Cox, 1839’, D 3063(L). Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Casey, Melba and Rolly Gilbert 1986, ‘Kurtjar Stories’, School of Australian Linguistics, Darwin Institute of Technology. -

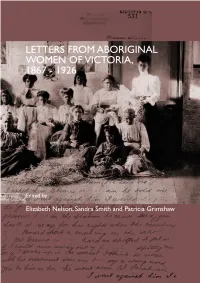

Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867-1926, Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw (2002)

LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw History Department The University of Melbourne 2002 © 2002 Copyright is held on individual letters by the individual contributors or their descendants. No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved. Published in 2002 by The History Department The University of Melbourne Melbourne, Australia The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Letters from aboriginal women in Victoria, 1867-1926. ISBN 0 7340 2160 7. 1. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Correspondence. 2. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Social conditions. 3. Aborigines, Australian - Government policy - Victoria. 4. Victoria - History. I. Grimshaw, Patricia, 1938- . II. Nelson, Elizabeth, 1972- . III. Smith, Sandra, 1945- . IV. University of Melbourne. Dept. of History. (Series : University of Melbourne history research series ; 11). 305.8991509945 Front cover details: ‘Raffia workers at Coranderrk’ Museum of Victoria Photographic Collection Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria Layout and cover design by Design Space TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 7 Map 9 Introduction 11 Notes on Editors 21 The Letters: Children and family 25 Land and housing 123 Asserting personal freedom 145 Regarding missionaries and station managers 193 Religion 229 Sustenance and material assistance 239 Biographical details of the letter writers 315 Endnotes 331 Publications 357 Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867 - 1926 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We have been helped to pursue this project by many people to whom we express gratitude. Patricia Grimshaw acknowledges the University of Melbourne Small ARC Grant for the year 2000 which enabled transcripts of the letters to be made. -

Provenance 2015

Provenance 2015 Issue 14, 2015 ISSN: 1832-2522 Index About Provenance 2 Editorial 4 Refereed articles 6 Patricia Grimshaw and Hannah Loney ‘Doing their bit helping make Australia free’: Mothers of Aboriginal diggers and the assertion of Indigenous rights 7 James Kirby Beyond failure and success: The soldier settlement on Ercildoune Road 18 Cassie May Lithium and lost souls: The role of Bundoora Homestead as a repatriation mental hospital 1920–1993 30 Dr Cate O’Neill ‘She had always been a difficult case …’ : Jill’s short, tragic life in Victoria’s institutions, 1952–1955 40 Amber Graciana Evangelista ‘… From squalor and vice to virtue and knowledge …’: The rise of Melbourne’s Ragged School system 56 Barbara Minchinton Reading the papers: The Victorian Lands Department’s influence on the occupation of the Otways under the nineteenth century land Acts 71 Peter Davies, Susan Lawrence and Jodi Turnbull Historical maps, geographic information systems (GIS) And complex mining landscapes on the Victorian goldfields 85 Forum articles 93 Dr David J Evans John Jones: A builder of early West Melbourne 94 Jennifer McNeice Military exemption courts in 1916: A public hearing of private lives 106 Dorothy Small An Innocent Pentonvillain: Thomas Drewery, chemist and exile 1821-1859 115 Janet Lynch The families of World War I veterans: Mental illness and Mont Park 123 Research journeys 130 Jacquie Browne Who says ‘you can’t change history’? 131 1 About Provenance The journal of Public Record Office Victoria Provenance is a free journal published online by Editorial Board Public Record Office Victoria. The journal features peer- reviewed articles, as well as other written contributions, The editorial board includes representatives of: that contain research drawing on records in the state • Public Record Office Victoria access services; archives holdings. -

Creating White Australia

Creating White Australia Edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Published 2009 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Fisher Library, University of Sydney www.sup.usyd.edu.au © Individual authors 2009 © Sydney University Press 2009 Reproduction and communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library University of Sydney NSW Australia 2006 Email: [email protected] National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Creating white Australia / edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky. ISBN: 9781920899424 (pbk.) Subjects: White Australia policy. Racism--Australia. Australia--Emigration and immigration--History. Australia--Race relations--History. Other Authors/Contributors: Carey, Jane, 1972- McLisky, Claire. Dewey Number: 305.80094 Cover design by Evan Shapiro, University Publishing Service, The University of Sydney Printed in Australia Contents Contributors ......................................................................................... v Introduction Creating White Australia: new perspectives on race, whiteness and history ............................................................................................ ix Jane Carey & Claire McLisky Part 1: Global -

Published in Australia the Women's Library Author Title Format Publisher Date

Published in Australia The Women's Library Author Title Format Publisher Date Non-Fiction Allen, Judith Sex and Secrets Book Oxford University Press Amirah Inglis The Hammer & The Sickle and the washing up Book Hyland House 1995 Anne Summers Damned whores and God's Police Book Penguin 1975 Damned Whores and God's Police, The Colonization of Women Book Penguin 1975 in Australia Archer Robyn Women's Role Book George Allen &Unwin 1983 Audrey Oldfield Australian Women and the Vote Book Cambridge 1994 Bell, Anita Your Mortgage and How to Pay it off in 5 Years Random House Australia Briddock, Barbara 2001 Hints for Hassle-Free Living Child & Associates Caine, Barbara Australian Feminism Book Oxford University Press Carol O'Donnell The Basis of the Bargain: Gender, Schooling and Jobs Book George Allen & 1984 Unwin 7/03/2017 1 Published in Australia The Women's Library Author Title Format Publisher Date Caroline Ambrus The Unseen Art Scene: 32 Australian Women Artists Book Irrepressible Press 1995 China Galland The Bond Between Women Book Hodder Headline 1998 Claire Halliday Do You Want Sex With That? Book Viking, Penguin 2009 Books Debra Vinecombe Women Tell Their Stories Book Wakefield Press 2008 Denfeld, Rene The New Victorians Book Allen and Unwin Denise Thompson Freedom for What? Journal DA Thompson 1984 Diane Bell ed. Kungun Ngarrindjeri Miminar Yunnan Book Spinifex Press 2008 Dianna Kelly-Byrne The Gendered Framing of English Teaching: A Selective Case Book Deakin University 1991 Study Donna Lee Brien , Tess Brady The Girls guide to work -

Creating White Australia

Creating White Australia Edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Published 2009 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Fisher Library, University of Sydney www.sup.usyd.edu.au © Individual authors 2009 © Sydney University Press 2009 Reproduction and communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library University of Sydney NSW Australia 2006 Email: [email protected] National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Creating white Australia / edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky. ISBN: 9781920899424 (pbk.) Subjects: White Australia policy. Racism--Australia. Australia--Emigration and immigration--History. Australia--Race relations--History. Other Authors/Contributors: Carey, Jane, 1972- McLisky, Claire. Dewey Number: 305.80094 Cover design by Evan Shapiro, University Publishing Service, The University of Sydney Printed in Australia Contents Contributors ......................................................................................... v Introduction Creating White Australia: new perspectives on race, whiteness and history ............................................................................................ ix Jane Carey & Claire McLisky Part 1: Global -

Creating White Australia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship Creating White Australia Edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Published 2009 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Fisher Library, University of Sydney www.sup.usyd.edu.au © Individual authors 2009 © Sydney University Press 2009 Reproduction and communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library University of Sydney NSW Australia 2006 Email: [email protected] National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Creating white Australia / edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky. ISBN: 9781920899424 (pbk.) Subjects: White Australia policy. Racism--Australia. Australia--Emigration and immigration--History. Australia--Race relations--History. Other Authors/Contributors: Carey, Jane, 1972- McLisky, Claire. Dewey Number: 305.80094 Cover design by Evan Shapiro, University Publishing Service, The University of Sydney Printed in Australia Contents Contributors ......................................................................................... v Introduction Creating White Australia: new perspectives on race, whiteness and history ...........................................................................................