Patricia Grimshaw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Chindhade Final Dissertation

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of German PRESENTING AND COMPARING EARLY MARATHI AND GERMAN WOMEN’S FEMINIST WRITINGS (1866-1933): SOME FINDINGS A Dissertation in German by Tejashri Chindhade © 2010 Tejashri Chindhade Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 The dissertation of Tejashri Chindhade was reviewed and approved* by the following: Daniel Purdy Associate Professor of German Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Thomas.O. Beebee Professor of Comparative Literature and German Reiko Tachibana Associate Professor of Japanese and Comparative Literature Kumkum Chatterjee Associate Professor of South Asia Studies B. Richard Page Associate Professor of German and Linguistics Head of the Department of German *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract In this dissertation I present the feminist writings of four Marathi women writers/ activists Savitribai Phule’s “ Prose and Poetry”, Pandita Ramabai’s” The High Caste Hindu Woman”, Tarabai Shinde’s “Stri Purush Tualna”( A comparison between women and men) and Malatibai Bedekar’s “Kalyanche Nihshwas”( “The Sighs of the buds”) from the colonial period (1887-1933) and compare them with the feminist writings of four German feminists: Adelheid Popp’s “Jugend einer Arbeiterin”(Autobiography of a Working Woman), Louise Otto Peters’s “Das Recht der Frauen auf Erwerb”(The Right of women to earn a living..), Hedwig Dohm’s “Der Frauen Natur und Recht” (“Women’s Nature and Privilege”) and Irmgard Keun’s “Gilgi: Eine Von Uns”(Gilgi:one of us) (1886-1931), respectively. This will be done from the point of view of deconstructing stereotypical representations of Indian women as they appear in westocentric practices. -

Australian Women, Past and Present

Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Edited by Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein and Mary Tomsic Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Diversity in leadership : Australian women, past and present / Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein, Mary Tomsic, editors. ISBN: 9781925021707 (paperback) 9781925021714 (ebook) Subjects: Leadership in women--Australia. Women--Political activity--Australia. Businesswomen--Australia. Women--Social conditions--Australia Other Authors/Contributors: Damousi, Joy, 1961- editor. Rubenstein, Kim, editor. Tomsic, Mary, editor. Dewey Number: 305.420994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Introduction . 1 Part I. Feminist perspectives and leadership 1 . A feminist case for leadership . 17 Amanda Sinclair Part II. Indigenous women’s leadership 2 . Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts . 39 Gwenda Baker, Joanne Garŋgulkpuy and Kathy Guthadjaka 3 . Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal rights . 53 Rachel Standfield, Ray Peckham and John Nolan Part III. Local and global politics 4 . Women’s International leadership . 71 Marilyn Lake 5 . The big stage: Australian women leading global change . 91 Susan Harris Rimmer 6 . ‘All our strength, all our kindness and our love’: Bertha McNamara, bookseller, socialist, feminist and parliamentary aspirant . -

11. Academic Women and Research Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia

11. Academic women and research leadership in twentieth-century Australia Patricia Grimshaw1 and Rosemary Francis2 While the focus of analysis of leadership in tertiary institutions is most commonly the capacities of the most senior academic administrators, many academics at less elevated levels in the hierarchy also can exert major influence in their disciplinary areas that has significant impact nationally and internationally. This chapter offers an insight into Australian women’s leadership in the academic profession in the twentieth century through the careers of outstanding scholars who from the mid 1950s were elected fellows of the Australian learned academies. Women faced considerable barriers to employment in universities before the expansion of secondary and tertiary education in the postwar years increased their opportunities to gain academic positions and advance the cutting edges of their disciplines. Yet, starting in 1956, when the first woman was elected to a learned academy, talented women were singled out as research leaders through this peer evaluation of their importance. With the social changes in gender expectations that the women’s movement inspired and the Australian Labor Party’s affirmative action policies of the 1980s, the number of female senior scholars who reached this standing increased markedly—noticeable especially in the humanities and social sciences. First, this chapter considers the careers of the first group of academicians who were elected to the four academies from 1956 to 1976; second, it traces the election of women from the late 1970s to the end of the century, including a few scholars who became leaders of the academies themselves. The story of academic women and research leadership is overall one of progressive change, but also indicates that gender equity has yet to be attained in the academic profession or, consequently, in the learned academies. -

Creating White Australia

Creating White Australia Edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Published 2009 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS Fisher Library, University of Sydney www.sup.usyd.edu.au © Individual authors 2009 © Sydney University Press 2009 Reproduction and communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library University of Sydney NSW Australia 2006 Email: [email protected] National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Creating white Australia / edited by Jane Carey and Claire McLisky. ISBN: 9781920899424 (pbk.) Subjects: White Australia policy. Racism--Australia. Australia--Emigration and immigration--History. Australia--Race relations--History. Other Authors/Contributors: Carey, Jane, 1972- McLisky, Claire. Dewey Number: 305.80094 Cover design by Evan Shapiro, University Publishing Service, The University of Sydney Printed in Australia Contents Contributors ......................................................................................... v Introduction Creating White Australia: new perspectives on race, whiteness and history ............................................................................................ ix Jane Carey & Claire McLisky Part 1: Global -

Biographies and Autobiographies of Historians, Edited by Doug Munro and John G

11 Country and Kin Calling? Keith Hancock, the National Dictionary Collaboration, and the Promotion of Life Writing in Australia1 Melanie Nolan Australian historians and ego-histoire In his international comparison of history, historians and autobiography in 2005, Jeremy D. Popkin concluded that Australian historians were early to, and enthusiastic about, the ego-histoire movement or the ‘setting down [of] one’s own story’. Australians anticipated Pierre Nora’s collection of essays, Essais d’ego-histoire, which was published in 1987.2 They had already founded ‘a series of autobiographical lectures in 1984’, which resulted in a number of publications, and Australian historians’ memoirs thereafter appeared at a rate of more than one a year.3 When he considered Australian 1 I thank Ann Curthoys and the editors for their comments on an earlier draft. 2 Pierre Nora ed., Essais d’ego-histoire (Paris: Gallimard, 1987), 7. 3 Jeremy D. Popkin, History, Historians, & Autobiography (Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 74. In ‘Ego-histoire Down Under: Australian Historian-Autobiographers’, Australian Historical Studies, 38:129 (2007), 110, doi.org/10.1080/10314610708601234, Popkin dates the Australian memoir bulge from 1982 when collective projects including ‘a volume of professional women’s narratives, The Half-Open Door, which appeared in 1982, and the four volumes of essays starting with the Victorian History Institute’s 1984 forum in which R.M. Crawford, Manning Clark and Geoffrey Blainey participated’. Patricia Grimshaw and Lynne -

Gyn/Ecology the Metaethics of Radical Feminism

GYN/ECOLOGY THE METAETHICS OF RADICAL FEMINISM MARY DALY Beacon Press : Boston : 1978 N.B. Transcript omits footnotes and citations. PREFACE This book voyages beyond Beyond God the Father. It is not that I basically disagree with the ideas expressed there. I am still its author, and thus the situation is not comparable to that of The Church and the Second Sex, whose (1968) author I regard as a reformist foresister, and whose work I respectfully refute in the New Feminist Postchristian Introduction to the 1975 edition. Going beyond Beyond God the Father involves two things. First, there is the fact that be-ing continues. Be-ing at home on the road means continuing to Journey. This book continues to Spin on, in other directions/dimensions. It focuses beyond christianity in Other ways. Second, there is some old semantic baggage to be discarded so that Journeyers will be unencumbered by malfunctioning (male-functioning) equipment. There are some words which appeared to be adequate in the early seventies, which feminists later discovered to be false words. Three such words in BGTF which I cannot use again are God, androgyny, and homosexuality. There is no way to remove male/masculine imagery from God. Thus, when writing/speaking “anthropomorphically” of ultimate reality, of the divine spark of be-ing, I now choose to write/speak gynomorphically. I do so because God represents the necrophilia of patriarchy, whereas Goddess affirms the life-loving be-ing of women and nature. The second semantic abomination, androgyny, is a confusing term which I sometimes used in attempting to describe integrity of be-ing. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Archival material Australian Dictionary of Biography Files, Australian National University Archives, Canberra Correspondence to Professor Pike from John Kirkland Wilson Pike, 7 December 1965; Eaves Walton & Stewart, Legal & Historical Research papers, in ‘Katherine Kirkland Biographical File’. ‘David Cannon McConnel Biographical File’. National Library of Australia Index to Passengers to Sydney 1838–1842, Habart Samuel – Justus John, Archives Authority of New South Wales, AO Reel 4; Immigration Agents’ Immigration Lists, April 1838–November 1841:Assisted Immigration, NLA mfm N229, Archives Authority of NSW, Reel No. 2134. Flinders, M 1814, Chart of Terra Australis, Sheet III, East coast [cartographic material], G and W Nicol, London. Nathan F. Spielvogel, ‘When White Men First Looked on Ballarat’, NLA MS 3776. State Records Authority of New South Wales Reports of John Baxter, Joseph Corralis, Lieutenant Otter, Captain Foster Fyans and John Graham, SZ976, COD 183. State Library of New South Wales Martens, Conrad, ‘Bulimba on the Brisbane River, D. C. McConnel Esq., Nov. 21, 1851’, Pencil 19 x 29.5 cm (ML PXC972, f.3). ‘Scott family: mainly studio portraits of the Scott and Townsend families, ca. 1864–1886’, SLNSW, Sydney, PXB 276. 161 In the Eye of the Beholder State Library of Queensland, John Oxley Library, Brisbane McConnel, J C I 1963, ‘The Lives of Frederic and John [sic] Anne McConnel’, McConnel Family Papers, microform no. 755399. State Library of South Australia ‘Letter from George Gawler to Henry Cox, 1839’, D 3063(L). Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Casey, Melba and Rolly Gilbert 1986, ‘Kurtjar Stories’, School of Australian Linguistics, Darwin Institute of Technology. -

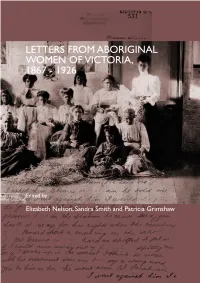

Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867-1926, Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw (2002)

LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw History Department The University of Melbourne 2002 © 2002 Copyright is held on individual letters by the individual contributors or their descendants. No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved. Published in 2002 by The History Department The University of Melbourne Melbourne, Australia The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Letters from aboriginal women in Victoria, 1867-1926. ISBN 0 7340 2160 7. 1. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Correspondence. 2. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Social conditions. 3. Aborigines, Australian - Government policy - Victoria. 4. Victoria - History. I. Grimshaw, Patricia, 1938- . II. Nelson, Elizabeth, 1972- . III. Smith, Sandra, 1945- . IV. University of Melbourne. Dept. of History. (Series : University of Melbourne history research series ; 11). 305.8991509945 Front cover details: ‘Raffia workers at Coranderrk’ Museum of Victoria Photographic Collection Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria Layout and cover design by Design Space TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 7 Map 9 Introduction 11 Notes on Editors 21 The Letters: Children and family 25 Land and housing 123 Asserting personal freedom 145 Regarding missionaries and station managers 193 Religion 229 Sustenance and material assistance 239 Biographical details of the letter writers 315 Endnotes 331 Publications 357 Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867 - 1926 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We have been helped to pursue this project by many people to whom we express gratitude. Patricia Grimshaw acknowledges the University of Melbourne Small ARC Grant for the year 2000 which enabled transcripts of the letters to be made. -

A Sociolinguistic Analysis of Participants Co-Constructing the Learning Context in a Graduate-Level Seminar

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1992 A sociolinguistic analysis of participants co-constructing the learning context in a graduate-level seminar. Mary Louise Waite Rearick University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Rearick, Mary Louise Waite, "A sociolinguistic analysis of participants co-constructing the learning context in a graduate-level seminar." (1992). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SOCIOLINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF PARTICIPANTS CO-CONSTRUCTING THE LEARNING CONTEXT IN A GRADUATE-LEVEL SEMINAR A Dissertation Presented by MARY LOUISE WAITE REARICK Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May, 1992 School of Education © Copyright by Mary Louise Waite Rearick All Rights Reserved A SOCIOLINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF PARTICIPANTS CO-CONSTRUCTING THE LEARNING CONTEXT IN A GRADUATE-LEVEL SEMINAR A Dissertation Presented by MARY LOUISE WAITE REARICK Approved as to style and content by: Masha K. Rudman, Chair R. Mason Bunker, Member Bailey Jackson, Dea School of Education ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my family, for their love and encouragement enabled me to complete this project. Charles and Theresa Waite, my parents, nurtured my sense of wonder and competence. -

Women in the Life of the City

VICTORIAN WOMEN’S TRUST WOMEN IN THE LIFE OF THE CITY 1 WOMEN IN THE LIFE OF THE CITY VICTORIAN WOMEN’S TRUST Published and distributed by: WOMEN IN THE LIFE Victorian Women’s Trust @VicWomensTrust OF THE CITY a. Level 9, 313 La Trobe Street Melbourne 3000 p. (03) 9642 0422 e. [email protected] w. www.vwt.org.au CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 WOMEN & THE PUBLIC RECORD 6 WOMEN’S PROFILES 12 REFERENCES 38 This project was undertaken by Victorian Women’s Trust with research, profile writing and referencing provided by Megan Rosato, 2018. All images contained within are for educational purposes only. Not for reproduction. WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following material contains images of deceased persons. PLEASE NOTE: This material is intended for reference only. Permissions to honour these women in public projects will need to be sought on a project to project basis and should include family and community consultation. Women sorting cheques National Bank, Head office, 2 279 Collins Street, Melbourne, 1953 - Wolfgang Sievers 3 VICTORIAN WOMEN’S TRUST Members of the Australian WOMENWomen’s IN THE Army LIFE Service OF THE CITY (AWAS) give “eyes right” as they pass the saluting base during the Service Womens march through Melbourne, 1942. Introduction In late 2017, The City of Melbourne approached the Victorian Women’s Trust with a request for assistance in developing a list of notable women to address the gender bias in street naming. As putting women on the public record is an important touchstone of the Trust as an organisation, we were happy to roll up our sleeves and start researching notable women of Melbourne whose mighty contributions shaped the city, we live and work in. -

Patricia Grimshaw

WHITE MEN’S FEARS AND WHITE WOMEN’S HOPES THE 1908 VICTORIAN ADULT SUFFRAGE ACT Patricia Grimshaw HE PASSAGE IN 908 OF THE ADULT SUFFRAGE ACT that enfranchised women for Victoria’s state elections was the culmina- Ttion of a lengthy history of settler women’s activism. This activism stretched back to the 860s, when women ratepayers, already enfranchised for municipal elections, gladly utilised a loophole in a new electoral act to vote in the colony’s 864 election. The loophole was swiftly closed but the issue simmered away until the newly formed Victorian Women’s Suffrage Society began a concerted suffrage campaign in 884. At an in- ternational level, women’s suffrage in Victoria shares Australia’s fame as a site of early enfranchisement, most commonly recognised at the national level. The Commonwealth Franchise Act of 902 conferred on women the right to vote and stand for parliament at the federal level, recognition of the existing rights of women in South Australia and Western Australia, who received the colonial vote in 894 and 899 respectively.2 Outside of Australia, only in New Zealand and four western states of the United States of America had women also been enfranchised by 902. Most women in the western world awaited the conclusion of the first or second world wars for the same rights.3 2 Victorian Historical Journal Vol. 79, No. 2, November 2008 Within the Australian context, however, a concentration on the Com- monwealth Franchise Act could obscure the further events subsequent to this Act that brought about a fuller democracy within the separate colonies and states; it could also conceal the prolonged fragile status of Indigenous voters at state and federal level. -

WEL Informed Issue 416 Mar13

Issue No 416 March 2013 WEL-Informed The Newsletter of Women’s Electoral Lobby NSW Inside this issue: INTERNATIONAL WOMEN'S DAY MARCH 2013 Early Days of WEL 2 At midday on Saturday 9 March over 300 people gathered at Town Hall Square in Sydney for the annual International Women's Day march. An amazing array Punishing Sole 3 of women and supporters came from all over Sydney to mark this important Parents with Newstart day. (Continued on page 10) Convenor’s Report 4 Preached but not 5 Practised —The Work and Life Family Survey Women of the Year 6 Awards WEL Australia 7 Report Next WEL meeting Wednesday 3rd April 6.00 pm at 66 Albion Street Surry Hills ALL WELCOME RSVP 02 9212 4374 Or [email protected] WEL NSW Inc is a member of WEL Australia and is EARLY DAYS OF WEL – dedicated to creating a society where women’s THE BEGINNING OF MY POLITICISATION— ANNE BARBER participation and potential are unrestricted, acknow- I first joined WEL when I was in my last year of university and heard about the ledged and respected, where women’s movement – it was about 1974. I wasn’t a feminist back then but had women and men share equally in society’s been brought up with the belief that anyone (including females) should be able responsibilities and rewards. to tackle anything they wanted to in their life and career. WELNSW Office - I attended my first meeting at Humanist House in Chippendale. There were Phone/fax: (02) 9212 4374 about 50 women present and there was much debate and discussion about Email: [email protected] topics of which I knew absolutely nothing, and lots of plans made for various Website: activities.