Creating White Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merri Creek Sediment Project: a Model for Inter-Government Solution Development

Merri Creek Sediment Project: A model for Inter-Government Solution Development Melanie Holmes & Toby Prosser Melbourne Water Corporation, 990 La Trobe Street, Docklands VIC 3008 [email protected] [email protected] Background The Merri Creek, a tributary of Melbourne’s Yarra River, Figure 1: Merri Creek Catchment originates near Wallan, flowing 70km through Melbourne’s northern suburbs to its confluence near Dights Falls in Abbotsford. With a catchment of approximately 390 km2, it falls within the municipal areas of Darebin, Hume, Mitchell, Moreland, Whittlesea and City of Yarra. It is a high profile waterway, supporting good remnant ecological values in its upper, and, significant recreational values in its lower reaches. Merri Creek Management Committee (MCMC) and Friends of Merri Creek both play an active role in environmental protection and advocacy. As with other urban and peri urban waterways, Merri Creek is impacted by stormwater runoff from its catchment areas, varying in effect due to catchment activities and the level of impermeability. Merri Creek has been identified as Melbourne’s most polluted waterway (The Age, 2011), and has recently been subject to heavy rainfall driven sediment loads. This issue has also been the focus of community and media scrutiny, with articles in the Melbourne metropolitan daily newspaper (The Age) and local newspapers featuring MCMC discussing the damaging effects of stormwater inputs. Sediment is generated through the disturbance of soils within the catchment through vegetation removal, excavation, soil importation and dumping, as well as in stream erosion caused by altered flow regimes, such as increases in flow quantity, velocity and frequency as a result of urbanisation. -

Platypus Rescued Then Surveyed in Merri Creek

The Friends of Merri Creek Newsletter May – July 2012 Friends of Merri Creek is the proud winner of the 2011 Victorian Landcare Award Platypus rescued then surveyed in Merri Creek After a platypus was rescued from plastic litter in Merri Creek near Moreland Rd Coburg on 25 January, Melbourne Water commissioned a survey for platypus in the creek. A number of reliable platypus sightings in Merri Creek from Healesville Sanctuary, he was released back into over the past 18 months raised hopes that this iconic his territory in Merri Creek. Following this, Melbourne species may have recolonised one of Melbourne’s Water commissioned cesar to conduct surveys to try to most urbanised waterways after a very long absence. determine the extent of the distribution and relative Platypuses were apparently abundant in Merri Creek abundance of platypuses in Merri Creek. in the late 1800’s, but slowly disappeared as the creek In conjunction with the surveys, an information session and surrounding areas were degraded by the growing was held at CERES where more than 50 people turned urbanisation of Melbourne’s suburbs. Widespread surveys out to watch cesar ecologists demonstrate how fyke nets in Merri Creek in early 1995 by the Australian Platypus are set to catch platypuses, followed by a talk on platypus Conservancy failed to capture any platypuses, and it is biology and conservation issues. Live trapping surveys generally accepted that platypuses have been locally were conducted over two nights in February, sampling extinct in the creek for decades. Occasional sightings from Arthurton Rd to Bell St. The surveys involved near the confluence with the Yarra River have indicated setting pairs of fyke nets at a number of sites during the the potential for recolonisation by individuals entering afternoon, checking the nets throughout the night to from the Yarra River. -

The Future of the Yarra

the future of the Yarra ProPosals for a Yarra river Protection act the future of the Yarra A about environmental Justice australia environmental Justice australia (formerly the environment Defenders office, Victoria) is a not-for-profit public interest legal practice. funded by donations and independent of government and corporate funding, our legal team combines a passion for justice with technical expertise and a practical understanding of the legal system to protect our environment. We act as advisers and legal representatives to the environment movement, pursuing court cases to protect our shared environment. We work with community-based environment groups, regional and state environmental organisations, and larger environmental NGos. We also provide strategic and legal support to their campaigns to address climate change, protect nature and defend the rights of communities to a healthy environment. While we seek to give the community a powerful voice in court, we also recognise that court cases alone will not be enough. that’s why we campaign to improve our legal system. We defend existing, hard-won environmental protections from attack. at the same time, we pursue new and innovative solutions to fill the gaps and fix the failures in our legal system to clear a path for a more just and sustainable world. envirojustice.org.au about the Yarra riverkeePer association The Yarra Riverkeeper Association is the voice of the River. Over the past ten years we have established ourselves as the credible community advocate for the Yarra. We tell the river’s story, highlighting its wonders and its challenges. We monitor its health and activities affecting it. -

Yarra's Topography Is Gently Undulating, Which Is Characteristic of the Western Basalt Plains

Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Acknowledgement of country ............................................................................................................................ 3 Message from the Mayor ................................................................................................................................... 4 Vision and goals ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Nature in Yarra .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Policy and strategy relevant to natural values ................................................................................................. 27 Legislative context ........................................................................................................................................... 27 What does Yarra do to support nature? .......................................................................................................... 28 Opportunities and challenges for nature ......................................................................................................... -

Land Hunger: Port Phillip, 1835

Land Hunger: Port Phillip, 1835 By Glen Foster An historical game using role-play and cards for 4 players from upper Primary school to adults. © Glen Foster, 2019 1 Published by Port Fairy Historical Society 30 Gipps Street, Port Fairy. 3284. Telephone: (03) 5568 2263 Email: [email protected] Postal address: Port Fairy Historical Society P.O. Box 152, Port Fairy, Victoria, 3284 Australia Copyright © Glen Foster, 2019 Reproduction and communication for educational and private purposes Educational institutions downloading this work are able to photocopy the material for their own educational purposes. The general public downloading this work are able to photocopy the material for their own private use. Requests and enquiries for further authorisation should be addressed to Glen Foster: email: [email protected]. Disclaimers These materials are intended for education and training and private use only. The author and Port Fairy Historical Society accept no responsibility or liability for any incomplete or inaccurate information presented within these materials within the poetic license used by the author. Neither the author nor Port Fairy Historical Society accept liability or responsibility for any loss or damage whatsoever suffered as a result of direct or indirect use or application of this material. Print on front page shows members of the Kulin Nations negotiating a “treaty” with John Batman in 1835. Reproduced courtesy of National Library of Australia. George Rossi Ashton, artist. © Glen Foster, 2019 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION -

Red-Browed Finches in MCMC Garden Learning About Nature

Merri News FEBRUARY 2012 The quarterly newsletter of Merri Creek Management Committee (MCMC) - caring for the Merri Creek Red-browed Finches in MCMC garden In late 2011 a small group of native Red-browed Finches were regular visitors to MCMC’s front garden. The finches fed on the seed of Clustered Wallaby-grass (Austrodanthonia racemosa) and the berries of Nodding Saltbush (Einadia nutans). A MCMC staff member has also seen the finches nearby on Merri Creek in East Brunswick, in grasses that were planted in July 2011. These bird visits show the value of using indigenous plants to quickly create habitat, even in a small garden area. Merri Creek Guided Bike Rides Sunday 15 April 10am-1pm - Preston Departing Robinsons Reserve Preston we will head downstream focusing on Darebin’s wetlands Sunday 29 April 10am-1pm - Whittlesea From City of Whittlesea Public Gardens, through Galada Tamboore and onto the new path alongside Merri Creek, discovering creatures and landscapes. Each ride is approx 8km return. BYO lunch to these family friendly events. Booking is essential – contact Jane on 93808199 or [email protected] Friends of Merri Creek win 2011 Learning about nature through art Victorian Urban Landcare Award MCMC congratulates our member group, Friends of MCMC works closely with people living in the Merri Merri Creek, upon winning the 2011 Victorian Urban Creek catchment to protect and promote indigenous Landcare award. This is on top of winning the 2010 Port biodiversity. We have been using printing as a way to Phillip & Westernport Landcare Award, Community develop community knowledge with a variety of groups Group Caring for Public Land. -

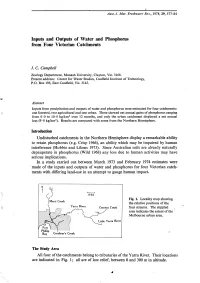

Inputs and Outputs of Water and Phosphorus from Four Victorian Catchments

Aust. J. Mar. Freshwater Res., 1978, 29, 577-84 Inputs and Outputs of Water and Phosphorus from Four Victorian Catchments /. C. Campbell Zoology Department, Monash University, Clayton, Vic. 3168. Present address: Centre for Water Studies, Caulfield Institute of Technology, P.O. Box 195, East Caulfield, Vic. 3145, Abstract Inputs from precipitation and outputs of water and phosphorus were estimated for four catchments: one forested, two agricultural and one urban. Three showed net annual gains of phosphorus ranging from 6-0 to 10-8 kg/km^ over 12 months, and only the urban catchment displayed a net annual loss (9 • 8 kg/km^). Results are compared with some from the Northern Hemisphere. Introduction Undisturbed catchments in the Northern Hemisphere display a remarkable abiUty to retain phosphorus (e.g. Crisp 1966), an ability which may be impaired by human interference (Hobbie and Likens 1973). Since Australian soils are already naturally depauperate in phosphorus (Wild 1968) any loss due to human activities may have serious impUcations. In a study carried out between March 1973 and February 1974 estimates were made of the inputs and outputs of water and phosphorus for four Victorian catch• ments with differing land-use in an attempt to gauge human impact. Fig. 1. Locality map showing the relative positions of the four streams. The stippled area indicates the extent of the Melbourne urban area. The Study Area All four of the catchments belong to tributaries of the Yarra River. Their locations are indicated in Fig. 1; all are of low rehef, between 0 and 300 m in altitude. 578 I. -

William Barak

WILLIAM BARAK A brief essay about William Barak drawn from the booklet William Barak - Bridge Builder of the Kulin by Gibb Wettenhall, and published by Aboriginal Affairs Victoria. Barak was educated at the Yarra Mission School in Narrm (Melbourne), and was a tracker in the Native Police before, as his father had done, becoming ngurungaeta (clan leader). Known as energetic, charismatic and mild mannered, he spent much of his life at Coranderrk Reserve, a self-sufficient Aboriginal farming community in Healesville. Barak campaigned to protect Coranderrk, worked to improve cross-cultural understanding and created many unique artworks and artefacts, leaving a rich cultural legacy for future generations. Leader William Barak was born into the Wurundjeri clan of the Woi wurung people in 1823, in the area now known as Croydon, in Melbourne. Originally named Beruk Barak, he adopted the name William after joining the Native Police as a 19 year old. Leadership was in Barak's blood: his father Bebejan was a ngurunggaeta (clan head) and his Uncle Billibellary, a signatory to John Batman's 1835 "treaty", became the Narrm (Melbourne) region's most senior elder. As a boy, Barak witnessed the signing of this document, which was to have grave and profound consequences for his people. Soon after white settlement a farming boom forced the Kulin peoples from their land, and many died of starvation and disease. During those hard years, Barak emerged as a politically savvy leader, skilled mediator and spokesman for his people. In partnership with his cousin Simon Wonga, a ngurunggaeta, Barak worked to establish and protect Coranderrk, a self- sufficient Aboriginal farming community in Healesville, and became a prominent figure in the struggle for Aboriginal rights and justice. -

Billibellary's

Billibellary’s Walk A cultural interpretation of the landscape that provides an experience of connection to country which Wurundjeri people continue to have, both physically and spiritually. Lying within the University of Melbourne’s built environment are the whispers and songs of the Wurundjeri people. As one of the clans of the Kulin Nation, the Wurundjeri people of the Woiwurrung language group walked the grounds upon which the University now stands for more than 40,000 years Stop 4 – Aboriginal Knowledge Stop 10 – Billibellary’s Country Aboriginal knowledge, bestowed through an oral tradition, is What would Billibellary think if he were to walk with you ever-evolving, enabling it to reflect its context. Sir Walter Baldwin now? The landscape has changed but while it looks Spencer, the University’s foundation professor of Biology in 1887, different on the surface Billibellary might remind you it still was highly esteemed for his anthropological and ethnographic holds the story of the Wurundjeri connection to Country work in Aboriginal communities but the Aboriginal community and our continuing traditions. today regards this work as a misappropriation of Aboriginal culture and knowledge. Artist: Kelly Koumalatsos, Wergaia/Wemba Wemba, Stop 5 – Self-determination and Community Control Possum Skin Cloak, Koorie Heritage Trust collection. Murrup Barak, Melbourne Indigenous Development Institute represents the fight that Billibellary, the Wurundjeri people, and Take a walk through Billibellary’s Country. indeed the whole Kulin nation were to face. The institute’s name Feel, know, imagine Melbourne’s six uses Woiwurung language to speak of the spirit of William Barak, seasons as they are subtly reconstructed Billibellary’s nephew and successor as Ngurungaeta to the as the context for understanding place and Wurundjeri Willam. -

Australian Women, Past and Present

Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Edited by Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein and Mary Tomsic Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Diversity in leadership : Australian women, past and present / Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein, Mary Tomsic, editors. ISBN: 9781925021707 (paperback) 9781925021714 (ebook) Subjects: Leadership in women--Australia. Women--Political activity--Australia. Businesswomen--Australia. Women--Social conditions--Australia Other Authors/Contributors: Damousi, Joy, 1961- editor. Rubenstein, Kim, editor. Tomsic, Mary, editor. Dewey Number: 305.420994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Introduction . 1 Part I. Feminist perspectives and leadership 1 . A feminist case for leadership . 17 Amanda Sinclair Part II. Indigenous women’s leadership 2 . Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts . 39 Gwenda Baker, Joanne Garŋgulkpuy and Kathy Guthadjaka 3 . Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal rights . 53 Rachel Standfield, Ray Peckham and John Nolan Part III. Local and global politics 4 . Women’s International leadership . 71 Marilyn Lake 5 . The big stage: Australian women leading global change . 91 Susan Harris Rimmer 6 . ‘All our strength, all our kindness and our love’: Bertha McNamara, bookseller, socialist, feminist and parliamentary aspirant . -

Moreland Pre-Contact Aboriginal Heritage Study (The Study)

THE CITY OF MORELAND Pre-ContactP AboriginalRECONTA HeritageCT Study 2010 ABORIGINAL HERITAGE STUDY THE CITY OF MORELAND PRECONTACT ABORIGINAL HERITAGE STUDY Prepared for The City of Moreland ������������������ February 2005 Prepared for The City of Moreland ������������������ February 2005 Suite 3, 83 Station Street FAIRFIELD MELBOURNE 3078 Phone: (03) 9486 4524 1243 Fax: (03) 9481 2078 Suite 3, 83 Station Street FAIRFIELD MELBOURNE 3078 Phone: (03) 9486 4524 1243 Fax: (03) 9481 2078 Acknowledgement Acknowledgement of traditional owners Moreland City Council acknowledges Moreland as being on the traditional lands of the Wurundjeri people. Council pays its respects to the Wurundjeri people and their Elders, past and present. The Wurundjeri Tribe Land Council, as the Registered Aboriginal Party (RAP) and the Traditional Owners for the whole of the Moreland City Council area, should be the first point of contact for any future enquiries, reports, events or similar that include any Pre-contact Aboriginal information. Statement of committment (Taken from the Moreland Reconciliation Policy and Action Plan 2008-2012) Moreland City Council gives its support to the Australian Declaration Towards Reconciliation 2000 and the National Apology to the Stolen Generations by the Australian Parliament 13 February 2008. It makes the following Statement of Commitment to Indigenous People. Council recognises • That Indigenous Australians were the first people of this land. • That the Wurundjeri are the traditional owners of country now called Moreland. • The centrality of Indigenous issues to Australian identity. • That social and cultural dispossession has caused the current disadvantages experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. • That Indigenous people have lost their land, their children, their health and their lives and regrets these losses. -

Patricia Grimshaw

Patricia Grimshaw 100 YEARS OF WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE 1908-2008 Reflection and Celebration Patricia Grimshaw Limited edition handmade publication 2007 Printed and Handbound RMIT University Students from School of Architecture and Design & School of Global Studies,Social Science and Planning Lecturer/Project Manager: Fern Smith Facilitation: Liam Fennessy and Soumitri Varadarajan Project Partners: Women’s Electoral Lobby and League of Women Voters Victoria Adjunct Professor Judith Smart background material on women’s suffrage in Victoria Shawn Callahan of anecdote for opening question techniques Meg Minos for background material on bookbinding Jackie Ralph for transcribing Interviewee: Patricia Grimshaw Interviewed by: Diana White and Sarah Costanzo Interview of Patricia Grimshaw edited by Diana White Copyright: 2007 Patricia Grimshaw I would like to dedicate this to all women fighting for equality Sarah Costanzo Introduction The 24th of November 1908 marks the day when the Legislative Council passed a suffrage bill enabling women for the fi rst time to vote in state elections of Victoria, Australia. For the centenary celebration Liam Fennessy and Sou- mitri Varadarajan, RMIT Industrial Design Program, Kerry Lovering Women’s Electoral Lobby, Sheila Byard Victoria League of Women Voters Victoria and artist Fern Smith worked in partnership; facilitating RMIT students to produce handmade limited edition books of twelve signifi cant women in Victoria. Four students Emma Brelsford, Sarah Costanzo, Cara Jeffery and Diana White conducted twelve two hour interviews with Gracia Baylor, Elleni Bereded-Samuel, Ellen Chandler, Angela Clarke, Ursula Dutkiewicz, Beatrice Faust, Pat Goble, Professor Patricia Grimshaw, Mary Owen, Marian Quartly, Associate Professor Jenny Strauss and Eleanor Sumner. The students had never interviewed, edited nor produced handmade books it is a fantastic achievement with in a twelve-week semester.