State of the Environment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrated Water Management Strategy 2040 – Towards a Water Sensitive City

Moreland City Council Integrated Water Management Strategy 2040 – Towards a Water Sensitive City Version 01 / November 2019 1 D20/175902 Contents Integrated Water Management Strategy – Toward a Water Sensitive City ........................................... 3 Vision ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Aim .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 A Water Sensitive City ............................................................................................................................. 6 What would a water sensitive city look like? .......................................................................................... 7 Moreland Context ................................................................................................................................... 8 Our Catchments ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Moreland’s Role as a Water Manager .................................................................................................... 9 An integrated stakeholder and partner approach ................................................................................ 10 The Challenges We Face Today ............................................................................................................ -

Merri Creek Sediment Project: a Model for Inter-Government Solution Development

Merri Creek Sediment Project: A model for Inter-Government Solution Development Melanie Holmes & Toby Prosser Melbourne Water Corporation, 990 La Trobe Street, Docklands VIC 3008 [email protected] [email protected] Background The Merri Creek, a tributary of Melbourne’s Yarra River, Figure 1: Merri Creek Catchment originates near Wallan, flowing 70km through Melbourne’s northern suburbs to its confluence near Dights Falls in Abbotsford. With a catchment of approximately 390 km2, it falls within the municipal areas of Darebin, Hume, Mitchell, Moreland, Whittlesea and City of Yarra. It is a high profile waterway, supporting good remnant ecological values in its upper, and, significant recreational values in its lower reaches. Merri Creek Management Committee (MCMC) and Friends of Merri Creek both play an active role in environmental protection and advocacy. As with other urban and peri urban waterways, Merri Creek is impacted by stormwater runoff from its catchment areas, varying in effect due to catchment activities and the level of impermeability. Merri Creek has been identified as Melbourne’s most polluted waterway (The Age, 2011), and has recently been subject to heavy rainfall driven sediment loads. This issue has also been the focus of community and media scrutiny, with articles in the Melbourne metropolitan daily newspaper (The Age) and local newspapers featuring MCMC discussing the damaging effects of stormwater inputs. Sediment is generated through the disturbance of soils within the catchment through vegetation removal, excavation, soil importation and dumping, as well as in stream erosion caused by altered flow regimes, such as increases in flow quantity, velocity and frequency as a result of urbanisation. -

Platypus Rescued Then Surveyed in Merri Creek

The Friends of Merri Creek Newsletter May – July 2012 Friends of Merri Creek is the proud winner of the 2011 Victorian Landcare Award Platypus rescued then surveyed in Merri Creek After a platypus was rescued from plastic litter in Merri Creek near Moreland Rd Coburg on 25 January, Melbourne Water commissioned a survey for platypus in the creek. A number of reliable platypus sightings in Merri Creek from Healesville Sanctuary, he was released back into over the past 18 months raised hopes that this iconic his territory in Merri Creek. Following this, Melbourne species may have recolonised one of Melbourne’s Water commissioned cesar to conduct surveys to try to most urbanised waterways after a very long absence. determine the extent of the distribution and relative Platypuses were apparently abundant in Merri Creek abundance of platypuses in Merri Creek. in the late 1800’s, but slowly disappeared as the creek In conjunction with the surveys, an information session and surrounding areas were degraded by the growing was held at CERES where more than 50 people turned urbanisation of Melbourne’s suburbs. Widespread surveys out to watch cesar ecologists demonstrate how fyke nets in Merri Creek in early 1995 by the Australian Platypus are set to catch platypuses, followed by a talk on platypus Conservancy failed to capture any platypuses, and it is biology and conservation issues. Live trapping surveys generally accepted that platypuses have been locally were conducted over two nights in February, sampling extinct in the creek for decades. Occasional sightings from Arthurton Rd to Bell St. The surveys involved near the confluence with the Yarra River have indicated setting pairs of fyke nets at a number of sites during the the potential for recolonisation by individuals entering afternoon, checking the nets throughout the night to from the Yarra River. -

The Future of the Yarra

the future of the Yarra ProPosals for a Yarra river Protection act the future of the Yarra A about environmental Justice australia environmental Justice australia (formerly the environment Defenders office, Victoria) is a not-for-profit public interest legal practice. funded by donations and independent of government and corporate funding, our legal team combines a passion for justice with technical expertise and a practical understanding of the legal system to protect our environment. We act as advisers and legal representatives to the environment movement, pursuing court cases to protect our shared environment. We work with community-based environment groups, regional and state environmental organisations, and larger environmental NGos. We also provide strategic and legal support to their campaigns to address climate change, protect nature and defend the rights of communities to a healthy environment. While we seek to give the community a powerful voice in court, we also recognise that court cases alone will not be enough. that’s why we campaign to improve our legal system. We defend existing, hard-won environmental protections from attack. at the same time, we pursue new and innovative solutions to fill the gaps and fix the failures in our legal system to clear a path for a more just and sustainable world. envirojustice.org.au about the Yarra riverkeePer association The Yarra Riverkeeper Association is the voice of the River. Over the past ten years we have established ourselves as the credible community advocate for the Yarra. We tell the river’s story, highlighting its wonders and its challenges. We monitor its health and activities affecting it. -

Yarra's Topography Is Gently Undulating, Which Is Characteristic of the Western Basalt Plains

Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Acknowledgement of country ............................................................................................................................ 3 Message from the Mayor ................................................................................................................................... 4 Vision and goals ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Nature in Yarra .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Policy and strategy relevant to natural values ................................................................................................. 27 Legislative context ........................................................................................................................................... 27 What does Yarra do to support nature? .......................................................................................................... 28 Opportunities and challenges for nature ......................................................................................................... -

Red-Browed Finches in MCMC Garden Learning About Nature

Merri News FEBRUARY 2012 The quarterly newsletter of Merri Creek Management Committee (MCMC) - caring for the Merri Creek Red-browed Finches in MCMC garden In late 2011 a small group of native Red-browed Finches were regular visitors to MCMC’s front garden. The finches fed on the seed of Clustered Wallaby-grass (Austrodanthonia racemosa) and the berries of Nodding Saltbush (Einadia nutans). A MCMC staff member has also seen the finches nearby on Merri Creek in East Brunswick, in grasses that were planted in July 2011. These bird visits show the value of using indigenous plants to quickly create habitat, even in a small garden area. Merri Creek Guided Bike Rides Sunday 15 April 10am-1pm - Preston Departing Robinsons Reserve Preston we will head downstream focusing on Darebin’s wetlands Sunday 29 April 10am-1pm - Whittlesea From City of Whittlesea Public Gardens, through Galada Tamboore and onto the new path alongside Merri Creek, discovering creatures and landscapes. Each ride is approx 8km return. BYO lunch to these family friendly events. Booking is essential – contact Jane on 93808199 or [email protected] Friends of Merri Creek win 2011 Learning about nature through art Victorian Urban Landcare Award MCMC congratulates our member group, Friends of MCMC works closely with people living in the Merri Merri Creek, upon winning the 2011 Victorian Urban Creek catchment to protect and promote indigenous Landcare award. This is on top of winning the 2010 Port biodiversity. We have been using printing as a way to Phillip & Westernport Landcare Award, Community develop community knowledge with a variety of groups Group Caring for Public Land. -

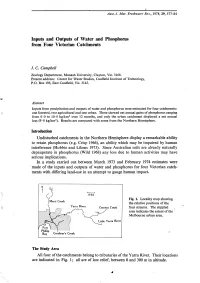

Inputs and Outputs of Water and Phosphorus from Four Victorian Catchments

Aust. J. Mar. Freshwater Res., 1978, 29, 577-84 Inputs and Outputs of Water and Phosphorus from Four Victorian Catchments /. C. Campbell Zoology Department, Monash University, Clayton, Vic. 3168. Present address: Centre for Water Studies, Caulfield Institute of Technology, P.O. Box 195, East Caulfield, Vic. 3145, Abstract Inputs from precipitation and outputs of water and phosphorus were estimated for four catchments: one forested, two agricultural and one urban. Three showed net annual gains of phosphorus ranging from 6-0 to 10-8 kg/km^ over 12 months, and only the urban catchment displayed a net annual loss (9 • 8 kg/km^). Results are compared with some from the Northern Hemisphere. Introduction Undisturbed catchments in the Northern Hemisphere display a remarkable abiUty to retain phosphorus (e.g. Crisp 1966), an ability which may be impaired by human interference (Hobbie and Likens 1973). Since Australian soils are already naturally depauperate in phosphorus (Wild 1968) any loss due to human activities may have serious impUcations. In a study carried out between March 1973 and February 1974 estimates were made of the inputs and outputs of water and phosphorus for four Victorian catch• ments with differing land-use in an attempt to gauge human impact. Fig. 1. Locality map showing the relative positions of the four streams. The stippled area indicates the extent of the Melbourne urban area. The Study Area All four of the catchments belong to tributaries of the Yarra River. Their locations are indicated in Fig. 1; all are of low rehef, between 0 and 300 m in altitude. 578 I. -

Thornbury and Northcote Local Flood Guide

Thornbury & Northcote Local Flood Guide Local Flood Guide Flash flood information for Merri Creek and Darebin Creek Thornbury/ Northcote For flood emergency assistance call VICSES on 132 500 Reviewed: August 2019 Local Flood Guide Thornbury & Northcote The Thornbury Local Area The suburb of Thornbury is located in the City of Darebin and located approximately seven kilometres north of Melbourne’s Central Business District. Thornbury is bordered by the Merri Creek to the West and Darebin Creek to the East, with Darebin Creek running through the Northern part of the Municipality. Other waterways within the municipality are Edgars Creek, Central Creek and Salt Creek all of which are located in the north. Edgars and Central creeks flow into Merri Creek while Salt Creek flows into Darebin Creek. The map below shows the impact of a 1% flood in the Reservoir area. A 1% flood means there is a 1% chance a flood this size happening in any given year. This map is provided as a guide to possible flooding within the area. Disclaimer This map publication is presented by Victoria State Emergency Service for the purpose of disseminating emergency management information. The contents of the information has not been independently verified by Victoria State Emergency Service. No liability is accepted for any damage, loss or injury caused by errors or omissions in this information or for any action taken by any person in reliance upon it. Flood information is provided by Melbourne Water. 2 Local Flood Guide Thornbury & Northcote Are you at risk of flood? The City of Darebin is prone to flash flooding. -

Moreland Pre-Contact Aboriginal Heritage Study (The Study)

THE CITY OF MORELAND Pre-ContactP AboriginalRECONTA HeritageCT Study 2010 ABORIGINAL HERITAGE STUDY THE CITY OF MORELAND PRECONTACT ABORIGINAL HERITAGE STUDY Prepared for The City of Moreland ������������������ February 2005 Prepared for The City of Moreland ������������������ February 2005 Suite 3, 83 Station Street FAIRFIELD MELBOURNE 3078 Phone: (03) 9486 4524 1243 Fax: (03) 9481 2078 Suite 3, 83 Station Street FAIRFIELD MELBOURNE 3078 Phone: (03) 9486 4524 1243 Fax: (03) 9481 2078 Acknowledgement Acknowledgement of traditional owners Moreland City Council acknowledges Moreland as being on the traditional lands of the Wurundjeri people. Council pays its respects to the Wurundjeri people and their Elders, past and present. The Wurundjeri Tribe Land Council, as the Registered Aboriginal Party (RAP) and the Traditional Owners for the whole of the Moreland City Council area, should be the first point of contact for any future enquiries, reports, events or similar that include any Pre-contact Aboriginal information. Statement of committment (Taken from the Moreland Reconciliation Policy and Action Plan 2008-2012) Moreland City Council gives its support to the Australian Declaration Towards Reconciliation 2000 and the National Apology to the Stolen Generations by the Australian Parliament 13 February 2008. It makes the following Statement of Commitment to Indigenous People. Council recognises • That Indigenous Australians were the first people of this land. • That the Wurundjeri are the traditional owners of country now called Moreland. • The centrality of Indigenous issues to Australian identity. • That social and cultural dispossession has caused the current disadvantages experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. • That Indigenous people have lost their land, their children, their health and their lives and regrets these losses. -

Inquiry Into Recycling and Waste Management: Interim Report Iii

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Environment and Planning Committee Inquiry into recycling and waste management Interim report Parliament of Victoria Legislative Council Environment and Planning Committee Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2019 PP No 65, Session 2018-19 ISBN 978 1 925703 80 1 (print version), 978 1 925703 81 8 (PDF version) Committee membership CHAIR DEPUTY CHAIR Cesar Melhem Clifford Hayes Western Metropolitan Southern Metropolitan Bruce Atkinson Melina Bath Jeff Bourman David Limbrick Eastern Metropolitan Eastern Victoria Eastern Victoria South Eastern Metropolitan Andy Meddick Dr Samantha Ratnam Nina Taylor Sonja Terpstra Western Victoria Northern Metropolitan Southern Metropolitan Eastern Metropolitan Participating members Georgie Crozier, Southern Metropolitan Dr Catherine Cumming, Western Metropolitan Hon. David Davis, Southern Metropolitan Tim Quilty, Northern Victoria ii Legislative Council Environment and Planning Committee About the committee Functions The Legislative Council Environment and Planning Committee’s functions are to inquire into and report on any proposal, matter or thing concerned with the arts, environment and planning the use, development and protection of land. As a Standing Committee, it may inquire into, hold public hearings, consider and report on any Bills or draft Bills, annual reports, estimates of expenditure or other documents laid before the Legislative Council in accordance with an Act, provided these are relevant to its functions. Secretariat Michael Baker, Secretary Kieran Crowe, Inquiry Officer Alice Petrie, Research Assistant Justine Donohue, Administrative Officer Contact details Address Legislative Council Environment and Planning Committee Parliament of Victoria Spring Street EAST MELBOURNE VIC 3002 Phone 61 3 8682 2869 Email [email protected] Web https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/epc-lc This report is available on the Committee’s website. -

Coburg Hill the First New Development in the Moreland Area Under the New Targets Moreland’S Waterways

Site introduction Con Gantonas Melbourne Water Site Characteristics • Kodak Australasia headquarters from 1961-2004 • Located at 173-199 Elizabeth Street, Coburg North • 9km north of Melbourne CBD • 21 hectares in size • Located in Moreland • Edgars Creek lies to the west Background • Site rezoned in May 2009 • Development plan approved by the Minister for Planning in June 2010 for approximately 400 dwellings and retail • In 2010 site purchased by the Satterley Property Group • CPG (now Spiire) engaged by Satterley to undertake engineering services Feasibility Process • Melbourne Water provided comments on the Stormwater Drainage Master Plan • Spiire keen to work with Melbourne Water to explore innovative WSUD solutions to satisfy stormwater quality treatment requirements in accordance with Clause 56: – stormwater quality options off site within the Edgars Creek drainage corridor – stormwater reuse at an allotment scale • Engaging with local community groups Melbourne Water Response • Support for distributed WSUD treatment at a streetscape and allotment scale • Recommendation for stormwater harvesting • Waterway health requirements • Asset protection requirements for water main • Consultation with Friends of Edgars Creek • Subsequent submission and approval of MUSIC model Complete About to commence Complete Moreland City Council Stormwater Quality Targets Vaughn Grey Moreland City Council Stormwater Quality Targets • New stormwater quality targets released in Jan 2012 • Coburg Hill the first new development in the Moreland area under the -

Moreland North of Bell Street Heritage Study Volume 1 – Key Findings and Recommendations

Moreland North of Bell Street Heritage Study Volume 1 – Key findings and recommendations Final 21 April 2011 Prepared for City of Moreland MORELAND NORTH OF BELL STREET HERITAGE STUDY Context Pty Ltd 2011 Project Team: David Helms, Senior Consultant Louise Honman, Director Natica Schmeder, Consultant Jenny Walker, Project assistant Ian Travers, Consultant Report Register This report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled Moreland North of Bell Street Heritage Study. Volume 1: Key findings and recommendations undertaken by Context Pty Ltd in accordance with our internal quality management system. Project Issue Notes/description Issue date Issued to No. No. 1404 1 Draft Stage 2 report 14 September 2010 Kate Shearer 1404 2 Final Stage 2 report 29 October 2010 Kate Shearer 1404 3 Final Stage 2 report 5 November 2010 Kate Shearer 1404 4 Final Stage 2 report 21 April 2011 Kate Shearer 1404 5 Final Stage 2 report rev 12 August 2011 Kate Shearer Context Pty Ltd 22 Merri Street, Brunswick 3056 Phone 03 9380 6933 Facsimile 03 9380 4066 Email [email protected] Web www.contextpl.com.au ii VOLUME 1: KEY FINDINGS & RECOMMENDATIONS CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VI Purpose vi Assessment of heritage places and precincts vi Review of thematic history vi Review of Fawkner Cemetery (HO216) vii Review of 34 Finchley Avenue (HO222) vii Recommendations vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose 1 1.2 Study area 1 1.3 Background 1 1.4 Terminology 2 2. STAGE 1 OUTCOMES 3 2.1 Purpose 3 2.2 Approach and methodology 3 Preparation of the primary