Deconstructing Tishman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebuilding the Trade Center

Rebuilding the Trade Center An Interview with Larry A. Silverstein, President and Chief Executive Offi cer, Silverstein Properties, Inc. EDITORS’ NOTE In July 2001, Larry The progress at the Trade Center Silverstein completed the largest real site for many years was very slow. I estate transaction in New York his- was frustrated because I was able to tory when he signed a 99-year lease build 7 World Trade Center in a four- on the 10.6-million-square-foot World year time frame. Trade Center for $3.25 billion only to We went into the ground in 2002, see it destroyed in terrorist attacks six and by 2006, we fi nished it after every- weeks later on September 11, 2001. body had predicted that the building He is currently rebuilding the offi ce would never succeed. We fi nanced it component of the World Trade Center for 40 years. We leased it and today, site, a $7-billion project. Silverstein it’s over 90 percent rented. The build- owns and manages 120 Broadway, ing has been enormously successful. tenancies that have the capacity of occupying 120 Wall Street, 529 Fifth Avenue, Larry A. Silverstein (above); The sad thing is that with the bal- its entirety. So that is gratifying, especially since and 570 Seventh Avenue. In 2008, the World Trade Center ance of the site, we could have done that building is based upon the need of a tenant. Silverstein announced an agree- rendering (right) what we did on 7 if given the opportu- We have the same level of interest in Tower ment with Four Seasons Hotels and nity to do so. -

Financing Affordable Rental Housing: Defining Success Five Case Studies

Financing Affordable Rental Housing: Defining Success Five Case Studies Bessy M. Kong and Derek Hsiang Financing Affordable Rental Housing: Defining Success Five Case Studies Bessy: Defining M. Kong and Derek Hsiang Success Five Case Studies ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was produced with the support and collaboration of the Korea Housing and Urban Guarantee Corporation (HUG) as a part of a joint research initiative with the Urban Sustainability Lab- oratory of the Wilson Center to examine public finance programs to increase the supply of affordable rental housing in the United States and Korea. The authors would like to thank HUG leadership and research partners, including Sung Woo Kim, author of the Korean report, and Dongsik Cho, for his support of the HUG-Wilson Center part- nership. We would also like to thank Michael Liu, Director of the Miami-Dade County Department of Public Housing and Commu- nity Development, for sharing his knowledge and expertise to in- form this research and for presenting the work in a research sem- inar and exchange in Seoul in November 2016. We are grateful to Alven Lam, Director of International Markets, Office of Capital Market at GinnieMae, for providing critical guidance for this joint research initiative and for his contribution to the Seoul seminar. Thanks to those who provided information for the case studies: Jorge Cibran and José A. Rodriguez (Collins Park); Andrew Gross and Michael Miller (Skyline Village); and, Robert Bernardin and Marianne McDermott (Pond View Village). A special acknowl- edgement to Allison Garland who read all the drafts; to Marina Kurokawa who helped with the initial research; and to Wallah Elshekh and Carly Giddings who assisted in proof reading and the formatting of the bibliography, footnotes and appendices. -

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project Lynne B. Sagalyn THREE YEARS after the terrorist attack of September 11,2001, plans for four key elements in rebuilding the World Trade Center (WC) site had been adopted: restoring the historic streetscape, creating a new public transportation gate- way, building an iconic skyscraper, and fashioning the 9/11 memorial. Despite this progress, however, what ultimately emerges from this heavily argued deci- sionmakmg process will depend on numerous design decisions, financial calls, and technical executions of conceptual plans-or indeed, the rebuilding plan may be redefined without regard to plans adopted through 2004. These imple- mentation decisions will determine whether new cultural attractions revitalize lower Manhattan and whether costly new transportation investments link it more directly with Long Island's commuters. These decisions will determine whether planned open spaces come about, and market forces will determine how many office towers rise on the site. In other words, a vision has been stated, but it will take at least a decade to weave its fabric. It has been a formidable challenge for a city known for its intense and frac- tious development politics to get this far. This chapter reviews the emotionally charged planning for the redevelopment of the WTC site between September 2001 and the end of 2004. Though we do not yet know how these plans will be reahzed, we can nonetheless examine how the initial plans emerged-or were extracted-from competing ambitions, contentious turf battles, intense architectural fights, and seemingly unresolvable design conflicts. World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project 25 24 Contentious City ( rebuilding the site. -

Minutes from the Monthly Meeting of Manhattan Community Board # 1 Held October 27, 2009 South Street Seaport Museum

MINUTES FROM THE MONTHLY MEETING OF MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD # 1 HELD OCTOBER 27, 2009 SOUTH STREET SEAPORT MUSEUM Public Hearing (5:30 PM) Public Hearing on Capital and Expense Budget Requests for FY 2011. No speakers signed up for the hearing and it was adjourned at 6:00 PM. Public Session City Council Member-Elect Margaret Chin The Council Member-elect greeted board members and said she’s looking forward to working with CB1 commencing in January 2010. She proposed that CB1 change its meeting date to avoid conflicting with CB3’s meeting which also occurs on the fourth Tuesday. Henry Korn, Attorney for 145 Hudson Street Thanked the Tribeca committee for recommending approval of the application for a special permit for 145 Hudson Street. Matthew Peckham, Architect for 145 Hudson Street Also thanked the Tribeca committee for the resolution. NYS Senator Daniel Squadron The Senator informed us that parent resource guides are available for the 25th Senate District Hosted a meeting with newly appointed S.L.A Chair Dennis Rosen. Anticipates conducting a town hall meeting in January. Launched Chinese Hotline 917-247-2348. People can call this number to request assistance from his office in the Mandarin and Cantonese dialects. Borough President Scott Stringer The Borough President praised Senator Daniel Squadron as a leader whom we are fortunate to have represent our District. Reported that we now have 2 new schools, but our search for additional space must continue due to the population growth in the area. Warned that while drilling into the earth near the Catskill/Delaware watershed in order to extract gas may seem appealing, it’s dangerous and can affect our drinking water, most of which originates there. -

Chairman's Award

THE NEW YORK LANDMARKS CONSERVANCY CHAIRMAN’S AWARD February 23, 2021 Chairman’s Award The New York Landmarks Conservancy inaugurated the Chairman’s Award in 1988 to recognize exceptional individuals, organizations, and businesses that have demonstrated their dedication to protecting New York’s architectural legacy. About Us The Conservancy’s singular mission for nearly fifty years has been the protection of New York’s built environment – from the iconic buildings that define the City’s spectacular skyline to the diverse neighborhoods where we live, work, and play. We are a strong voice for sound preservation policies. We are also the only organization that empowers New Yorkers with financial and technical assistance to restore their historic homes, cultural, religious, and social institutions. Our grants and loans of $53 million have mobilized more than $1 billion in some 2,000 renovation projects throughout the State, revitalizing communities, creating economic stimulus, and supporting local jobs. While most of our work is with individual homeowners and other nonprofit organizations, our achievements have included such high profile projects as the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, Moynihan Station, Fraunces Tavern block, Federal Archive Building, Astor Row, Ellis Island, and the establishment of the Lower Manhattan Preservation Fund following the terrorist attacks of September 11th. The New York Landmarks Conservancy One Whitehall Street, 21st Floor New York, NY 10004-2127 nylandmarks.org On the cover: 550 Madison Avenue, photo courtesy of The Olayan Group TWA Terminal at JFK Airport, photo courtesy of TWA Hotel, David Mitchell THE NEW YORK LANDMARKS CONSERVANCY 2021 CHAIRMAN’S AWARD honoring Rick Cotton Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Erik Horvat The Olayan Group Tyler Morse MCR February 23, 2021 12:00 pm Virtual Award Presentation 12:30 – 1:00 pm Virtual Networking Reception Leadership Committee Chair Frank J. -

APC WTC Thesis V8 090724

A Real Options Case Study: The Valuation of Flexibility in the World Trade Center Redevelopment by Alberto P. Cailao B.S. Civil Engineering, 2001 Wentworth Institute of Technology Submitted to the Center for Real Estate in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2009 ©2009 Alberto P. Cailao All rights reserved. The author hereby grants MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author________________________________________________________________________ Center for Real Estate July 24, 2009 Certified by_______________________________________________________________________________ David Geltner Professor of Real Estate Finance, Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by_____________________________________________________________________________ Brian A. Ciochetti Chairman, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development A Real Options Case Study: The Valuation of Flexibility in the World Trade Center Redevelopment by Alberto P. Cailao Submitted to the Center for Real Estate on July 24, 2009 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development Abstract This thesis will apply the past research and methodologies of Real Options to Tower 2 and Tower 3 of the World Trade Center redevelopment project in New York, NY. The qualitative component of the thesis investigates the history behind the stalled development of Towers 2 and 3 and examines a potential contingency that could have mitigated the market risk. The quantitative component builds upon that story and creates a hypothetical Real Options case as a framework for applying and valuing building use flexibility in a large-scale, politically charged, real estate development project. -

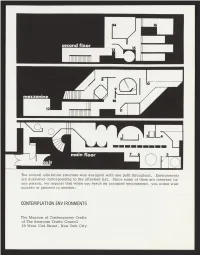

Contemplation Environments

The overall exhibition structure was designed with one path throughout. Environments are numbered corresponding to the attached list. Since many of them are intended for one person, we request that when you reach an occupied environment, you either wait outside or proceed to another. CONTEMPLATION ENVIRONMENTS The Museum of Contemporary Crafts of The American Crafts Council 29 West 53rd Street, New York City 1. US CO/INTERMEDIA, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Contemplative Sounds. 1969. Recorded tapes contained within two upholstered fiberglass chairs; courtesy Lee Company, Los Angeles, California. 2. NEKE CARSON, New York City. "Moon-Man Fountain". 1968. Domed trans- parent plastic environment for two with water. Conceived as fountain in which people are the sculpture. Optical experiences result from water- filled platform. 3. RALPH HAWKINS, New York City. Environment for casting the I Ching elec- tronically. 1969. Steel container lined with fresh moss, stones, and wood. I Ching, the "Book of Changes", is an ancient Chinese guide to life. 8'x4'x4'. 4. JACKIE CASSEN, Rudi Stern, New York City. LARRY SILVERSTEIN: engineer. "Iswara" (principle of regeneration, Sanskrit). 1969. Environment intended to create electronically the effects of meditation. Negative oxygen ions; spiraling oscilloscope pattern; low frequency sound. 5. ALEPH, New York City: SAM APPLE, HARRY FISCHMAN, PETER HEER, JON OLSON. Plexiglas column containing stroboscopic crystal waterfall which surrounds participant. 1970. Structural Plexiglas courtesy Rohm & Haas, Philadelphia, Pa. H'x6'. 6. VICTOR LUKENS, New York City. "Inner Space Object" . 1970. Mirrored Plexiglas double-domed environment. Material courtesy Rohm & Haas. Phila- delphia, Pa.; Cadillac Plastic & Chemical Co., Linden, New Jersey. 7. UGO LA PIETRA, Milan, Italy. -

The Park 51/Ground Zero Controversy and Sacred Sites As Contested Space

Religions 2011, 2, 297-311; doi:10.3390/rel2030297 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article The Park 51/Ground Zero Controversy and Sacred Sites as Contested Space Jeanne Halgren Kilde University of Minnesota, 245 Nicholson Hall, 216 Pillsbury Dr. SE., Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: 612-625-6393 Received: 9 June 2011; in revised form: 14 July 2011 / Accepted: 19 July 2011 / Published: 25 July 2011 Abstract: The Park 51 controversy swept like wildfire through the media in late August of 2010, fueled by Islamophobes who oppose all advance of Islam in America. Yet the controversy also resonated with many who were clearly not caught up in the fear of Islam. This article attempts to understand the broader concern that the Park 51 project would somehow violate the Ground Zero site, and, thus, as a sign of "respect" should be moved to a different location, an argument that was invariably articulated in “spatial language” as groups debated the physical and spatial presence of the buildings in question, their relative proximity, and even the shadows they cast. This article focuses on three sets of spatial meanings that undergirded these arguments: the site as sacred ground created through trauma, rebuilding as retaliation for the attack, and the assertion of American civil religion. The article locates these meanings within a broader civic discussion of liberty and concludes that the spatialization of the controversy opened up discursive space for repressive, anti-democratic views to sway even those who believe in religious liberty, thus evidencing a deep ambivalence regarding the legitimate civic membership of Muslim Americans. -

Negotiating the Mega-Rebuilding Deal at the World Trade Center: Plans for Redevelopment

NEGOTIATING THE MEGA-REBUILDING DEAL AT THE WORLD TRADE CENTER: PLANS FOR REDEVELOPMENT DARA M. MCQUILLAN* & JOHN LIEBER ** Good morning. The current state of Lower Manhattan is the result of multiple years of planning and refinement of designs. Later I will spend a couple of minutes discussing the various buildings that we are constructing. First, to give you a little sense of perspective, Larry Silverstein,1 a quintessential New York developer, first got involved at the World Trade Center and with the Port Authority, owner of the World Trade Center,2 in 1980 when he won a bid to build 7 World Trade Center.3 In 1987, Silverstein completed the seventh tower, just north of the World Trade Center site.4 As Alex mentioned, 7 World Trade Center was not the most attractive building in New York and completely cut off Greenwich Street. Greenwich Street is the main street running through Tribeca and connects one of the most dynamic and interesting neighborhoods in New York to the financial district.5 Greenwich serves as a major link to Wall Street. I used to live in SoHo. I would walk to work at the Twin Towers every morning down Greenwich Street past the Robert DeNiro Film Center, Bazzini‘s Nuts, the parks, and the lofts of movie stars, and all of a sudden I would be in front of a 656-foot brick wall of a building. There were huge wind vortexes which often swept garbage all over the place, you could never get a cab, and it was a very * Vice President of Marketing and Communications for World Trade Center Properties, LLC, and Silverstein Properties, Inc. -

Bill Perkins

BILL PERKINS ALBANY OFFICE SENATOR, 30TH DISTRICT LEGISLATIVE OFFICE BUILDING ROOM 817 COMMITTEE ASSIGNMENTS ALBANY, NY 12247 (P) 518-455-2441 CHAIR (F) 518-426-6809 Corporations, Authorities and Commissions DISTRICT OFFICE ACP STATE OFFICE BUILDING MEMBER 163 W. 125TH STREET, 9TH FL. Cities NEW YORK, NY 10027 Civil Service and Pensions (P) 212-222-7315 Codes (F) 212-678-0001 Judiciary Labor ALBANY OFFICE E-MAIL Transportation ROOM 617 [email protected] For immediate release Contact: Cordell Cleare 212-222-7315 or [email protected] NY Senate to Hold Hearings on WTC Delays State Senator Bill Perkins (D-New York) Chair of the Corporations, Authorities and Commissions Committee announced a Senate hearing next month on the stalled redevelopment of the World Trade Center. The impasse between the Port Authority and Silverstein Properties, a commercial developer threatens further delays. “This is an outrage,” said Perkins. “Eight years later Ground Zero remains an open wound. Where are our skyscrapers, transit hub, and Memorial already? Families are waiting for closure.” Larry Silverstein holds a lease to the site, but wants the PA, which owns the land, to guarantee financing of two office towers. The developer argues Authority delays led to having to seek financing in a down economy. The Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center predicts the PA‟s timetables will not be met. “The whole world watches as Ground Zero becomes an argument over money,” said Perkins. “Instead of a statement about democratic ideals and the resilience of the human spirit, we have an empty pit, a Memorial held hostage, blown deadlines, cost overruns, and construction workers and others out of work.” Silverstein requested arbitration regarding the PA‟s performance, which will cause further delay. -

The 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate

NEW YORK, THE REAL ESTATE Jerry Speyer Michael Bloomberg Stephen Ross Marc Holliday Amanda Burden Craig New- mark Lloyd Blankfein Bruce Ratner Douglas Durst Lee Bollinger Michael Alfano James Dimon David Paterson Mort Zuckerman Edward Egan Christine Quinn Arthur Zecken- dorf Miki Naftali Sheldon Solow Josef Ackermann Daniel Boyle Sheldon Silver Steve Roth Danny Meyer Dolly Lenz Robert De Niro Howard Rubinstein Leonard Litwin Robert LiMandri Howard Lorber Steven Spinola Gary Barnett Bill Rudin Ben Bernanke Dar- cy Stacom Stephen Siegel Pam Liebman Donald Trump Billy Macklowe Shaun Dono- van Tino Hernandez Kent Swig James Cooper Robert Tierney Ian Schrager Lee Sand- er Hall Willkie Dottie Herman Barry Gosin David Jackson Frank Gehry Albert Behler Joseph Moinian Charles Schumer Jonathan Mechanic Larry Silverstein Adrian Benepe Charles Stevenson Jr. Michael Fascitelli Frank Bruni Avi Schick Andre Balazs Marc Jacobs Richard LeFrak Chris Ward Lloyd Goldman Bruce Mosler Robert Ivanhoe Rob Speyer Ed Ott Peter Riguardi Scott Latham Veronica Hackett Robert Futterman Bill Goss Dennis DeQuatro Norman Oder David Childs James Abadie Richard Lipsky Paul del Nunzio Thomas Friedan Jesse Masyr Tom Colicchio Nicolai Ourouso! Marvin Markus Jonathan Miller Andrew Berman Richard Brodsky Lockhart Steele David Levinson Joseph Sitt Joe Chan Melissa Cohn Steve Cuozzo Sam Chang David Yassky Michael Shvo 100The 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate Bloomberg, Trump, Ratner, De Niro, the Guy Behind Craigslist! They’re All Among Our 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate ower. Webster’s Dictionary defines power as booster; No. 15 Edward Egan, the Catholic archbish- Governor David Paterson (No. -

Silver Art Projects Welcomes Inaugural Cohort of Artists-In-Residence at the World Trade Center, New York City and Launches Parallel Digital Arts Platform

Silver Art Projects Welcomes Inaugural Cohort of Artists-in-Residence at the World Trade Center, New York City and Launches Parallel Digital Arts Platform Following its creation in 2019, Silver Art Projects announces the 25 international artists, selected from a competitive field of more than 500 applicants, who will receive an unparalleled platform including studio space at 4 World Trade Center to expand their practices and to contribute to the cultural vitality of Lower Manhattan. Artists have begun moving in on a rolling schedule as New York City reopens. Left: Silver Art Projects at 4 World Trade Center. Courtesy Silver Art Projects. Photo by: Morgan Mein Right: Co-founders of Silver Art Projects, Cory Silverstein and Joshua Pulman. Courtesy Silver Art Projects. Photo by: Joe Woolhead. July 27, 2020 (New York) – Silver Art Projects, a nonprofit artist residency generously supported by Silverstein Properties—the real estate development firm that continues to lead the revival of Lower Manhattan through the rebuilding of the World Trade Center campus—has announced the 25 artists that will form its inaugural residency cohort. Following the announcement of the formation of Silver Art Residency in summer 2019, Silver Art Projects convened a jury of art world professionals who have overseen a competitive, multi-month selection process to determine the 25 creative individuals who will receive free of charge, purpose-built studio space, for up to eight months, at 4 World Trade Center. Artists have begun moving in on a rolling schedule following New York City’s gradual reopening. Set Downtown, in the heart of the World Trade Center’s network of Fortune 500 companies, tech startups, and creative enterprises, the Silver Art Residency occupies an entire floor of 4 WTC, and furthers Silverstein Properties’ commitment to placing contemporary art at the center of the reimagined Lower Manhattan.