Insurance and September 11 One Year After

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combating Islamic Extremist Terrorism 1

CGT 1/22/07 11:30 AM Page 1 Combating Islamic Extremist Terrorism 1 OVERALL GRADE D+ Al-Qaeda headquarters C+ Al-Qaeda affiliated groups C– Al-Qaeda seeded groups D+ Al-Qaeda inspired groups D Sympathizers D– 1 CGT 1/22/07 11:30 AM Page 2 2 COMBATING ISLAMIC EXTREMIST TERRORISM ive years after the September 11 attacks, is the United States win- ning or losing the global “war on terror”? Depending on the prism through which one views the conflict or the metrics used Fto gauge success, the answers to the question are starkly different. The fact that the American homeland has not suffered another attack since 9/11 certainly amounts to a major achievement. U.S. military and security forces have dealt al-Qaeda a severe blow, cap- turing or killing roughly three-quarters of its pre-9/11 leadership and denying the terrorist group uncontested sanctuary in Afghanistan. The United States and its allies have also thwarted numerous terror- ist plots around the world—most recently a plan by British Muslims to simultaneously blow up as many as ten jetliners bound for major American cities. Now adjust the prism. To date, al-Qaeda’s top leaders have sur- vived the superpower’s most punishing blows, adding to the near- mythical status they enjoy among Islamic extremists. The terrorism they inspire has continued apace in a deadly cadence of attacks, from Bali and Istanbul to Madrid, London, and Mumbai. Even discount- ing the violence in Iraq and Afghanistan, the tempo of terrorist attacks—the coin of the realm in the jihadi enterprise—is actually greater today than before 9/11. -

Payment System Disruptions and the Federal Reserve Followint

Working Paper Series This paper can be downloaded without charge from: http://www.richmondfed.org/publications/ Payment System Disruptions and the Federal Reserve Following September 11, 2001† Jeffrey M. Lacker* Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Richmond, Virginia, 23219, USA December 23, 2003 Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Working Paper 03-16 Abstract The monetary and payment system consequences of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks are reviewed and compared to selected U.S. banking crises. Interbank payment disruptions appear to be the central feature of all the crises reviewed. For some the initial trigger is a credit shock, while for others the initial shock is technological and operational, as in September 11, but for both types the payments system effects are similar. For various reasons, interbank payment disruptions appear likely to recur. Federal Reserve credit extension following September 11 succeeded in massively increasing the supply of banks’ balances to satisfy the disruption-induced increase in demand and thereby ameliorate the effects of the shock. Relatively benign banking conditions helped make Fed credit policy manageable. An interbank payment disruption that coincided with less favorable banking conditions could be more difficult to manage, given current daylight credit policies. Keywords: central bank, Federal Reserve, monetary policy, discount window, payment system, September 11, banking crises, daylight credit. † Prepared for the Carnegie-Rochester Conference on Public Policy, November 21-22, 2003. Exceptional research assistance was provided by Hoossam Malek, Christian Pascasio, and Jeff Kelley. I have benefited from helpful conversations with Marvin Goodfriend, who suggested this topic, David Duttenhofer, Spence Hilton, Sandy Krieger, Helen Mucciolo, John Partlan, Larry Sweet, and Jack Walton, and helpful comments from Stacy Coleman, Connie Horsley, and Brian Madigan. -

REVIEW of the TERRORIST ATTACKS on U.S. FACILITIES in BENGHAZI, LIBYA, SEPTEMBER 11-12,2012

LLIGE - REVIEW of the TERRORIST ATTACKS ON U.S. FACILITIES IN BENGHAZI, LIBYA, SEPTEMBER 11-12,2012 together with ADDITIONAL VIEWS January 15, 2014 SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE United States Senate 113 th Congress SSCI Review of the Terrorist Attacks on U.S. Facilities in Benghazi, Libya, September 11-12, 2012 I. PURPOSE OF TIDS REPORT The purpose of this report is to review the September 11-12, 2012, terrorist attacks against two U.S. facilities in Benghazi, Libya. This review by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (hereinafter "SSCI" or "the Committee") focuses primarily on the analy~is by and actions of the Intelligence Community (IC) leading up to, during, and immediately following the attacks. The report also addresses, as appropriate, other issues about the attacks as they relate to the Department ofDefense (DoD) and Department of State (State or State Department). It is important to acknowledge at the outset that diplomacy and intelligence collection are inherently risky, and that all risk cannot be eliminated. Diplomatic and intelligence personnel work in high-risk locations all over the world to collect information necessary to prevent future attacks against the United States and our allies. Between 1998 (the year of the terrorist attacks against the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania) and 2012, 273 significant attacks were carried out against U.S. diplomatic facilities and personnel. 1 The need to place personnel in high-risk locations carries significant vulnerabilities for the United States. The Conimittee intends for this report to help increase security and reduce the risks to our personnel serving overseas and to better explain what happened before, during, and after the attacks. -

Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Order Code RL32223 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Terrorist Organizations February 6, 2004 Audrey Kurth Cronin Specialist in Terrorism Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Huda Aden, Adam Frost, and Benjamin Jones Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations Summary This report analyzes the status of many of the major foreign terrorist organizations that are a threat to the United States, placing special emphasis on issues of potential concern to Congress. The terrorist organizations included are those designated and listed by the Secretary of State as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” (For analysis of the operation and effectiveness of this list overall, see also The ‘FTO List’ and Congress: Sanctioning Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, CRS Report RL32120.) The designated terrorist groups described in this report are: Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Armed Islamic Group (GIA) ‘Asbat al-Ansar Aum Supreme Truth (Aum) Aum Shinrikyo, Aleph Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group, IG) HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) Hizballah (Party of God) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya (JI) Al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK, KADEK) Lashkar-e-Tayyiba -

Rebuilding the Trade Center

Rebuilding the Trade Center An Interview with Larry A. Silverstein, President and Chief Executive Offi cer, Silverstein Properties, Inc. EDITORS’ NOTE In July 2001, Larry The progress at the Trade Center Silverstein completed the largest real site for many years was very slow. I estate transaction in New York his- was frustrated because I was able to tory when he signed a 99-year lease build 7 World Trade Center in a four- on the 10.6-million-square-foot World year time frame. Trade Center for $3.25 billion only to We went into the ground in 2002, see it destroyed in terrorist attacks six and by 2006, we fi nished it after every- weeks later on September 11, 2001. body had predicted that the building He is currently rebuilding the offi ce would never succeed. We fi nanced it component of the World Trade Center for 40 years. We leased it and today, site, a $7-billion project. Silverstein it’s over 90 percent rented. The build- owns and manages 120 Broadway, ing has been enormously successful. tenancies that have the capacity of occupying 120 Wall Street, 529 Fifth Avenue, Larry A. Silverstein (above); The sad thing is that with the bal- its entirety. So that is gratifying, especially since and 570 Seventh Avenue. In 2008, the World Trade Center ance of the site, we could have done that building is based upon the need of a tenant. Silverstein announced an agree- rendering (right) what we did on 7 if given the opportu- We have the same level of interest in Tower ment with Four Seasons Hotels and nity to do so. -

In Re: Terrorist Attacks on September 11, 2001

Case 1:03-md-01570-GBD-SN Document 3671 Filed 08/01/17 Page 1 of 33 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ____________________________________ ) IN RE: TERRORIST ATTACKS ON ) Civil Action No. 03 MDL 1570 (GBD) SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 ) ECF Case ____________________________________ ) This document relates to: Ashton, et al. v. al Qaeda, et al., No. 02-cv-6977 Federal Insurance Co., et al. v. al Qaida, et al., No. 03-cv-6978 Thomas Burnett, Sr., et al. v. Al Baraka Inv. & Dev. Corp., et al., No. 03-cv-9849 Continental Casualty Co., et al. v. Al Qaeda, et al., No. 04-cv-5970 Cantor Fitzgerald Assocs., et al. v. Akida Inv. Co., et al. No. 04-cv-7065 Euro Brokers Inc., et al. v. Al Baraka Inv. & Dev. Corp., et al., No. 04-cv-7279 McCarthy, et al. v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, No. 16-cv-8884 Aguilar, et al. v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, et al., No. 16-cv-9663 Addesso, et al. v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, et al., No. 16-cv-9937 Hodges, et al. v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, et al., No. 17-cv-117 DeSimone v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, No. 17-cv-348 Aiken, et al v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, et al., No. 17-cv-450 The Underwriting Members of Lloyd’s Syndicate 53, et al. v. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, et al., No. 17-cv-2129 The Charter Oak Fire Insurance Co., et al. v. Al Rajhi Bank, et al. No. 17-cv-02651 Abarca, et al. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

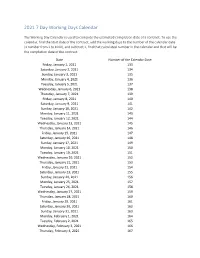

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

Financing Affordable Rental Housing: Defining Success Five Case Studies

Financing Affordable Rental Housing: Defining Success Five Case Studies Bessy M. Kong and Derek Hsiang Financing Affordable Rental Housing: Defining Success Five Case Studies Bessy: Defining M. Kong and Derek Hsiang Success Five Case Studies ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was produced with the support and collaboration of the Korea Housing and Urban Guarantee Corporation (HUG) as a part of a joint research initiative with the Urban Sustainability Lab- oratory of the Wilson Center to examine public finance programs to increase the supply of affordable rental housing in the United States and Korea. The authors would like to thank HUG leadership and research partners, including Sung Woo Kim, author of the Korean report, and Dongsik Cho, for his support of the HUG-Wilson Center part- nership. We would also like to thank Michael Liu, Director of the Miami-Dade County Department of Public Housing and Commu- nity Development, for sharing his knowledge and expertise to in- form this research and for presenting the work in a research sem- inar and exchange in Seoul in November 2016. We are grateful to Alven Lam, Director of International Markets, Office of Capital Market at GinnieMae, for providing critical guidance for this joint research initiative and for his contribution to the Seoul seminar. Thanks to those who provided information for the case studies: Jorge Cibran and José A. Rodriguez (Collins Park); Andrew Gross and Michael Miller (Skyline Village); and, Robert Bernardin and Marianne McDermott (Pond View Village). A special acknowl- edgement to Allison Garland who read all the drafts; to Marina Kurokawa who helped with the initial research; and to Wallah Elshekh and Carly Giddings who assisted in proof reading and the formatting of the bibliography, footnotes and appendices. -

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project Lynne B. Sagalyn THREE YEARS after the terrorist attack of September 11,2001, plans for four key elements in rebuilding the World Trade Center (WC) site had been adopted: restoring the historic streetscape, creating a new public transportation gate- way, building an iconic skyscraper, and fashioning the 9/11 memorial. Despite this progress, however, what ultimately emerges from this heavily argued deci- sionmakmg process will depend on numerous design decisions, financial calls, and technical executions of conceptual plans-or indeed, the rebuilding plan may be redefined without regard to plans adopted through 2004. These imple- mentation decisions will determine whether new cultural attractions revitalize lower Manhattan and whether costly new transportation investments link it more directly with Long Island's commuters. These decisions will determine whether planned open spaces come about, and market forces will determine how many office towers rise on the site. In other words, a vision has been stated, but it will take at least a decade to weave its fabric. It has been a formidable challenge for a city known for its intense and frac- tious development politics to get this far. This chapter reviews the emotionally charged planning for the redevelopment of the WTC site between September 2001 and the end of 2004. Though we do not yet know how these plans will be reahzed, we can nonetheless examine how the initial plans emerged-or were extracted-from competing ambitions, contentious turf battles, intense architectural fights, and seemingly unresolvable design conflicts. World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project 25 24 Contentious City ( rebuilding the site. -

9-11 and Terrorist Travel- Full

AND TERRORIST TRAVEL Staff Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States 9/11 AND TERRORIST TRAVEL Staff Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States By Thomas R. Eldridge Susan Ginsburg Walter T. Hempel II Janice L. Kephart Kelly Moore and Joanne M. Accolla, Staff Assistant Alice Falk, Editor Note from the Executive Director The Commission staff organized its work around specialized studies, or monographs, prepared by each of the teams. We used some of the evolving draft material for these studies in preparing the seventeen staff statements delivered in conjunction with the Commission’s 2004 public hearings. We used more of this material in preparing draft sections of the Commission’s final report. Some of the specialized staff work, while not appropriate for inclusion in the report, nonetheless offered substantial information or analysis that was not well represented in the Commission’s report. In a few cases this supplemental work could be prepared to a publishable standard, either in an unclassified or classified form, before the Commission expired. This study is on immigration, border security and terrorist travel issues. It was prepared principally by Thomas Eldridge, Susan Ginsburg, Walter T. Hempel II, Janice Kephart, and Kelly Moore, with assistance from Joanne Accolla, and editing assistance from Alice Falk. As in all staff studies, they often relied on work done by their colleagues. This is a study by Commission staff. While the Commissioners have been briefed on the work and have had the opportunity to review earlier drafts of some of this work, they have not approved this text and it does not necessarily reflect their views. -

Minutes from the Monthly Meeting of Manhattan Community Board # 1 Held October 27, 2009 South Street Seaport Museum

MINUTES FROM THE MONTHLY MEETING OF MANHATTAN COMMUNITY BOARD # 1 HELD OCTOBER 27, 2009 SOUTH STREET SEAPORT MUSEUM Public Hearing (5:30 PM) Public Hearing on Capital and Expense Budget Requests for FY 2011. No speakers signed up for the hearing and it was adjourned at 6:00 PM. Public Session City Council Member-Elect Margaret Chin The Council Member-elect greeted board members and said she’s looking forward to working with CB1 commencing in January 2010. She proposed that CB1 change its meeting date to avoid conflicting with CB3’s meeting which also occurs on the fourth Tuesday. Henry Korn, Attorney for 145 Hudson Street Thanked the Tribeca committee for recommending approval of the application for a special permit for 145 Hudson Street. Matthew Peckham, Architect for 145 Hudson Street Also thanked the Tribeca committee for the resolution. NYS Senator Daniel Squadron The Senator informed us that parent resource guides are available for the 25th Senate District Hosted a meeting with newly appointed S.L.A Chair Dennis Rosen. Anticipates conducting a town hall meeting in January. Launched Chinese Hotline 917-247-2348. People can call this number to request assistance from his office in the Mandarin and Cantonese dialects. Borough President Scott Stringer The Borough President praised Senator Daniel Squadron as a leader whom we are fortunate to have represent our District. Reported that we now have 2 new schools, but our search for additional space must continue due to the population growth in the area. Warned that while drilling into the earth near the Catskill/Delaware watershed in order to extract gas may seem appealing, it’s dangerous and can affect our drinking water, most of which originates there.