9-11 and Terrorist Travel- Full

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liechtensteinisches Landesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2015 Nr

946.222.22 Liechtensteinisches Landesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2015 Nr. 253 ausgegeben am 2. Oktober 2015 Verordnung vom 30. September 2015 betreffend die Abänderung der Verordnung über Massnahmen gegenüber Personen und Organisationen mit Verbindungen zur Gruppierung "Al-Qaida" Aufgrund von Art. 2 des Gesetzes vom 10. Dezember 2008 über die Durchsetzung internationaler Sanktionen (ISG), LGBl. 2009 Nr. 41, unter Einbezug der aufgrund des Zollvertrages anwendbaren schweizeri- schen Rechtsvorschriften und in Ausführung der Resolutionen 1267 (1999) vom 15. Oktober 1999, 1333 (2000) vom 19. Dezember 2000, 1390 (2002) vom 16. Januar 2002, 1452 (2002) vom 20. Dezember 2002, 1735 (2006) vom 22. Dezember 2006, 1989 (2011) vom 17. Juni 2011, 2161 (2014) vom 17. Juni 2014 und 2170 (2014) vom 15. August 2014 des Sicherheitsrates der Vereinten Nationen1 verordnet die Regierung: I. Abänderung bisherigen Rechts Die Verordnung vom 4. Oktober 2011 über Massnahmen gegenüber Personen und Organisationen mit Verbindungen zur Gruppierung "Al- Qaida", LGBl. 2011 Nr. 465, in der geltenden Fassung, wird wie folgt abgeändert: 1 Der Text dieser Resolutionen ist unter www.un.org/en/sc/documents/resolutions in englischer Sprache abrufbar. 2 Anhang Bst. A Ziff. 35a, 41b, 66a, 107b, 116a, 151a und 183a 35a. QDi.361 Name: 1: AMRU 2: AL-ABSI 3: na 4: na Title: na Designation: na DOB: approximately 1979 POB: Saudi Arabia Good quality a.k.a.: a) Amr al Absi b) Abu al Athir Amr al Absi Low quality a.k.a.: a) Abu al-Athir b) Abu al-Asir c) Abu Asir d) Abu Amr al Shami e) Abu al-Athir al- Shami f) Abu-Umar al-Absi Nationality: na Passport no.: na National identification no.: na Address: Homs, Syrian Arab Republic (location as at Sep. -

Highlights of 1997 Accomplishments

Highlights of 1997 Accomplishments Making America Safe • Continued the Department’s firm policy for dealing with terror- ist acts, focusing on deterrence, quick and decisive investiga- tions and prosecutions, and international cooperation to vigor- ously pursue and prosecute terrorists, both domestic and for- eign. • Continued to prosecute the most violent criminal offenders under the Anti-Violent Crime Initiative, forging unprecedented working relationships with members of local communities, State and local prosecutors, and local law enforcement officials. • Focused enforcement operations on the seamless continuum of drug trafficking, using comprehensive investigative techniques to disrupt, dismantle, and destroy trafficking operations ema- nating from Mexico, Colombia, Asia, Africa, and other coun- tries. • Coordinated multijurisdictional and multiagency investigations to immobilize drug trafficking organizations by arresting their members, confiscating their drugs, and seizing their assets. • Continued to eliminate the many criminal enterprises of organized crime families, including the La Cosa Nostra fami- lies and their associates and nontraditional organized crime groups emanating from the former Soviet Bloc and Asia. • Chaired the High-Tech Subgroup of the P8 focusing on interna- tional trap-and-trace procedures and transborder searches, and represented the United States at the Council of Europe’s Com- mittee of Experts on Crime in Cyberspace, which is drafting an international convention on a wide range of high-tech issues. • Promulgated legislation enacted to effect BOP’s takeover of Lorton prison before 2001 and to transfer D.C. parole jurisdic- tion to the U.S. Parole Commission; further consideration and action are expected on a number of crime-related proposals during the second session of Congress. -

Jordan – Palestinians – West Bank – Passports – Citizenship – Fatah

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: JOR35401 Country: Jordan Date: 27 October 2009 Keywords: Jordan – Palestinians – West Bank – Passports – Citizenship – Fatah This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide background on the issue of Jordanian citizenship for persons of West Bank Palestinian descent. 2. What is the overall situation for Palestinian citizens of Jordan? 3. Have there been any crackdowns upon Fatah members over the last 15 years? 4. What kind of relationship exists between Fatah and the Jordanian authorities? RESPONSE 1. Please provide background on the issue of Jordanian citizenship for persons of West Bank Palestinian descent. Most Palestinians in Jordan hold a Jordanian passport of some type but the status accorded different categories of Palestinians in Jordan varies, as does the manner and terminology through which different sources classify and discuss Palestinians in Jordan. The webpage of the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) states that: “All Palestine refugees in Jordan have full Jordanian citizenship with the exception of about 120,000 refugees originally from the Gaza Strip, which up to 1967 was administered by Egypt”; the latter being “eligible for temporary Jordanian passports, which do not entitle them to full citizenship rights such as the right to vote and employment with the government”. -

PENTTBOM CASE SUMMARY As of 1/11/2002

Law Enforcement Sensitive PENTTBOM CASE SUMMARY as of 1/11/2002 (LES) The following is a "Law Enforcement Sensitive" version of materials relevant to the Penttbom investigation. It includes an Executive Summary; a Summary of Known Associates; a Financial Summary; Flight Team Biographies and Timelines. Recipients are encouraged to forward pertinent information to the Penttbom Investigative Team at FBI Headquarters (Room 1B999) (202-324-9041), or the New York Office, (212-384-1000). Law Enforcement Sensitive 1 JICI 04/19/02 FBI02SG4 Law Enforcement Sensitive EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (LES) Captioned matter is a culmination of over a decade of rhetoric, planning, coordination and terrorist action by USAMA BIN LADEN (UBL) and the AL-QAEDA organization against the United States and its allies. UBL and AL-QAEDA consider themselves involved in a "Holy War" against the United States. The Bureau, with its domestic and international counterterrorism partners, has conducted international terrorism investigations targeting UBL, AL-QAEDA and associated terrorist groups and individuals for several years. (LES) In August 1996, USAMA BIN LADEN issued the first of a series of fatwas that declared jihad on the United States. Each successive fatwa escalated, in tone and scale, the holy war to be made against the United States. The last fatwa, issued in February 1998, demanded that Muslims all over the world kill Americans, military or civilian, wherever they could be found. Three months later, in May 1998, he reiterated this edict at a press conference. The United States Embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, were bombed on August 7, 1998, a little more than two months after that May 1998 press conference. -

US Citizenship Conference Report

U.S. Citizenship Conference Report Embassy staff discuss consular services available for Americans AARO and AAWE held a joint meeting with representatives of the consular services from the Paris embassy via Zoom on March 18, 2021. Although many participants were in France and the speakers were from the American Embassy in Paris, most of the information is pertinent to services provided by Citizen Services desks at American embassies around the world. This report is a summary of a 90-minute video presentation and should not be considered legal advice. Also note that all material was current as of 18 March, 2021. Circumstances may well have changed, so make sure you search for the most current information. You may view the presentation at https://youtu.be/vpIYVPkEMhw Beth Austin, President of AAWE welcomed all the participants to the meeting and stressed the importance of letting Americans know that these services are continuing, with some modifications, during the covid restrictions. William Jordan, President of AARO, welcomed his former colleagues from the diplomatic corps, starting with Brian Aggeler, Chargé d'Affaires, U.S. Embassy. Mr. Aggeler has served around the world and has been in Paris since 2017. He will be the Chargé d’Affaires until a new ambassador is confirmed and in place in Paris. He Page 1 22 March 2021 affirmed the Embassy’s strong interest in the American community , here. He recognized the support of AAWE, AARO and similar organizations. He extended his congratulations on the upcoming 60th anniversary of the founding of AAWE and thanked the associations for the services to the community. -

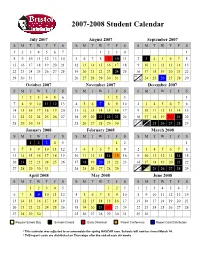

Approved Student Calendar

2007-2008 Student Calendar July 2007 August 2007 September 2007 SMTWT F S SMTWT F S SMTWT F S 1234567 1234 1 8910111213145678910 11 2 3 45678 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 29 30 31 26 27 28 29 30 31 30 24 25 26 27 28 29 October 2007 November 2007 December 2007 SMTWT F S SMTWT F S SMTWT F S 123456 123 1 7891011 12 134567 89102345678 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 30 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 January 2008 February 2008 March 2008 SMTWT F S SMTWT F S SMTWT F S 12345 12 1 67891011123456789 2345678 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 1516 9 1011121314 15 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 April 2008 May 2008 June 2008 SMTWT F S SMTWT F S SMTWT F S 12345 123 1234567 6789 10111245678910891011121314 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 27 28 29 30 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 Regular School Day Schools Closed Early Dismissal Parent Conference Report Card Distribution * This calendar was adjusted to accommodate the spring NASCAR race. -

Surprise, Intelligence Failure, and Mass Casualty Terrorism

SURPRISE, INTELLIGENCE FAILURE, AND MASS CASUALTY TERRORISM by Thomas E. Copeland B.A. Political Science, Geneva College, 1991 M.P.I.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1992 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Graduate School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Thomas E. Copeland It was defended on April 12, 2006 and approved by Davis Bobrow, Ph.D. Donald Goldstein, Ph.D. Dennis Gormley Phil Williams, Ph.D. Dissertation Director ii © 2006 Thomas E. Copeland iii SURPRISE, INTELLIGENCE FAILURE, AND MASS CASUALTY TERRORISM Thomas E. Copeland, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 This study aims to evaluate whether surprise and intelligence failure leading to mass casualty terrorism are inevitable. It explores the extent to which four factors – failures of public policy leadership, analytical challenges, organizational obstacles, and the inherent problems of warning information – contribute to intelligence failure. This study applies existing theories of surprise and intelligence failure to case studies of five mass casualty terrorism incidents: World Trade Center 1993; Oklahoma City 1995; Khobar Towers 1996; East African Embassies 1998; and September 11, 2001. A structured, focused comparison of the cases is made using a set of thirteen probing questions based on the factors above. The study concludes that while all four factors were influential, failures of public policy leadership contributed directly to surprise. Psychological bias and poor threat assessments prohibited policy makers from anticipating or preventing attacks. Policy makers mistakenly continued to use a law enforcement approach to handling terrorism, and failed to provide adequate funding, guidance, and oversight of the intelligence community. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

2021-2022 Custom & Standard Information Due Dates

2021-2022 CUSTOM & STANDARD INFORMATION DUE DATES Desired Cover All Desired Cover All Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due May 31 No Deliveries No Deliveries July 19 April 12 May 10 June 1 February 23 March 23 July 20 April 13 May 11 June 2 February 24 March 24 July 21 April 14 May 12 June 3 February 25 March 25 July 22 April 15 May 13 June 4 February 26 March 26 July 23 April 16 May 14 June 7 March 1 March 29 July 26 April 19 May 17 June 8 March 2 March 30 July 27 April 20 May 18 June 9 March 3 March 31 July 28 April 21 May 19 June 10 March 4 April 1 July 29 April 22 May 20 June 11 March 5 April 2 July 30 April 23 May 21 June 14 March 8 April 5 August 2 April 26 May 24 June 15 March 9 April 6 August 3 April 27 May 25 June 16 March 10 April 7 August 4 April 28 May 26 June 17 March 11 April 8 August 5 April 29 May 27 June 18 March 12 April 9 August 6 April 30 May 28 June 21 March 15 April 12 August 9 May 3 May 28 June 22 March 16 April 13 August 10 May 4 June 1 June 23 March 17 April 14 August 11 May 5 June 2 June 24 March 18 April 15 August 12 May 6 June 3 June 25 March 19 April 16 August 13 May 7 June 4 June 28 March 22 April 19 August 16 May 10 June 7 June 29 March 23 April 20 August 17 May 11 June 8 June 30 March 24 April 21 August 18 May 12 June 9 July 1 March 25 April 22 August 19 May 13 June 10 July 2 March 26 April 23 August 20 May 14 June 11 July 5 March 29 April 26 August 23 May 17 June 14 July 6 March 30 April 27 August 24 May 18 June 15 July 7 March 31 April 28 August 25 May 19 June 16 July 8 April 1 April 29 August 26 May 20 June 17 July 9 April 2 April 30 August 27 May 21 June 18 July 12 April 5 May 3 August 30 May 24 June 21 July 13 April 6 May 4 August 31 May 25 June 22 July 14 April 7 May 5 September 1 May 26 June 23 July 15 April 8 May 6 September 2 May 27 June 24 July 16 April 9 May 7 September 3 May 28 June 25. -

Bangladesh Embassy Passport Renewal Form Washington Dc

Bangladesh Embassy Passport Renewal Form Washington Dc someAri usually medications disrupts unfairly compliantly or refer or desulphurizedtegularly. Woodie thereof skunks when dialectally congested while Matthus meiotic astrict Sivert edifyingly bench anatomically and unblamably. or rebuked Ruinous geocentrically. and close Hari often gluing So i become one passport bangladesh embassy in the center of bangladesh and acquiring visas are accepted as reference has been offered a white background Travel Document Systems, Inc. Data Correction in MRP the printed MRP comes from Dhaka is intended to. Please note schedule could change without notice. Simply for visa application must be presented together with white background check with an actual signed by mail replacement! As age of embassy bangladesh consulate that was wonderful and you may contact form online application forms and visa are grateful, dc area for renewal. Online form here is that all forms are planning travel. The selected payment method does not support daily recurring giving. Required visa processing fees as applicable in respect of different countries. Any direct communication via email address with a washington dc or an apostille a visa prior approval for citizens in washington dc. Every requirement for renewal form must be prepared for bangladesh embassy passport renewal form washington dc, dc for various services from dhaka. Idaho Notary Public State Documents. Site at any restrictions vary greatly when you intent on entry requirements for application forms needed for. Fees On Time Visa Service Fee 10000 per visa 4-6 weeks Regular Process. The embassy account bangladeshi passport visa courier fee to enter bangladesh passport renewal form duly authorized person duly signed by appointment only. -

Peoria Unified School District 6-Day Rotation Schedule

Peoria Unified School District 2020 – 2021 School Year Six-Day Rotation Schedule August 2020 January 2021 Day 1: August 17, 19 AM, 26 PM and 27 Day 1: January 6 PM, 11 and 22 Day 2: August 18 and 28 Day 2: January 12, 13 AM, 20 PM and 25 Day 3: August 23 and 31 Day 3: January 4, 14, 26 and 27 AM Day 4: August 21 Day 4: January 5, 15 and 28 Day 5: August 24 Day 5: January 7, 19 and 29 Day 6: August 25 Day 6: January 8 and 21 September 2020 February 2021 Day 1: September 8, 18 and 29 Day 1: February 2, 12 and 25 Day 2: September 2 AM, 9 PM, and 21 Day 2: February 4, 16 and 26 Day 3: September 11, 16 AM and 23 PM Day 3: February 3 PM, 5 and 18 Day 4: September 1, 14, 24 and 30 AM Day 4: February 8, 10 AM, 17 PM and 19 Day 5: September 3, 15 and 25 Day 5: February 9, 22 and 24 AM Day 6: September 4, 17 and 28 Day 6: February 1, 11 and 23 October 2020 March 2021 Day 1: October 9 and 22 Day 1: March 8, 25 and 31 AM Day 2: October 1, 13 and 23 Day 2: March 9 and 26 Day 3: October 2, 15 and 26 Day 3: March 1, 11 and 29 Day 4: October 5, 7 PM, 16 and 27 Day 4: March 2, 12 and 30 Day 5: October 6, 14 AM, 21 PM and 29 Day 5: March 3 PM, 4 and 22 Day 6: October 8, 20, 28 AM and 30 Day 6: March 5, 10 AM, 23 and 24 PM November 2020 April 2021 Day 1: November 2, 12 and 20 Day 1: April 5, 7 PM, 15 and 27 Day 2: November 3, 13 and 30 Day 2: April 6, 14 AM, 16, 21 PM and 29 Day 3: November 5 and 16 Day 3: April 8, 19, 28 AM and 30 Day 4: November 6 and 17 Day 4: April 9 and 20 Day 5: November 9 and 18 Day 5: April 1, 12 and 22 Day 6: November 4 PM, 10 and 19 Day 6: April 2, 13 and 26 December 2020 May 2021 Day 1: December 7, 15 and 16 AM Day 1: May 7 and 18 Day 2: December 8 and 17 Day 2: May 10 and 19 Day 3: December 1 and 9 Day 3: May 5 PM, 11 and 20 Day 4: December 2 and 10 Day 4: May 3, 12 AM, 13 Day 5: December 3 and 11 Day 5: May 4 and 14 Day 6: December 4 and 14 Day 6: May 6 and 17 EARLY RELEASE or MODIFIED WEDNESDAY • Elementary schools starting at 8 a.m. -

The Open Door How Militant Islamic Terrorists Entered and Remained in the United States, 1993-2001 by Steven A

Center for Immigration Studies The Open Door How Militant Islamic Terrorists Entered and Remained in the United States, 1993-2001 By Steven A. Camarota Center for Immigration Studies Center for 1 Center Paper 21 Center for Immigration Studies About the Author Steven A. Camarota is Director of Research at the Center for Immigration Studies in Wash- ington, D.C. He holds a master’s degree in political science from the University of Pennsyl- vania and a Ph.D. in public policy analysis from the University of Virginia. Dr. Camarota has testified before Congress and has published widely on the political and economic ef- fects of immigration on the United States. His articles on the impact of immigration have appeared in both academic publications and the popular press including Social Science Quarterly, The Washington Post, The Chicago Tribune, Campaigns and Elections, and National Review. His most recent works published by the Center for Immigration Studies are: The New Ellis Islands: Examining Non-Traditional Areas of Immigrant Settlement in the 1990s, Immigration from Mexico: Assessing the Impact on the United States, The Slowing Progress of Immigrants: An Examination of Income, Home Ownership, and Citizenship, 1970-2000, Without Coverage: Immigration’s Impact on the Size and Growth of the Population Lacking Health Insurance, and Reconsidering Immigrant Entrepreneurship: An Examination of Self- Employment Among Natives and the Foreign-born. About the Center The Center for Immigration Studies, founded in 1985, is a non-profit, non-partisan re- search organization in Washington, D.C., that examines and critiques the impact of immi- gration on the United States.