Compensation for Losses from the 9/11 Attacks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Payment System Disruptions and the Federal Reserve Followint

Working Paper Series This paper can be downloaded without charge from: http://www.richmondfed.org/publications/ Payment System Disruptions and the Federal Reserve Following September 11, 2001† Jeffrey M. Lacker* Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Richmond, Virginia, 23219, USA December 23, 2003 Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Working Paper 03-16 Abstract The monetary and payment system consequences of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks are reviewed and compared to selected U.S. banking crises. Interbank payment disruptions appear to be the central feature of all the crises reviewed. For some the initial trigger is a credit shock, while for others the initial shock is technological and operational, as in September 11, but for both types the payments system effects are similar. For various reasons, interbank payment disruptions appear likely to recur. Federal Reserve credit extension following September 11 succeeded in massively increasing the supply of banks’ balances to satisfy the disruption-induced increase in demand and thereby ameliorate the effects of the shock. Relatively benign banking conditions helped make Fed credit policy manageable. An interbank payment disruption that coincided with less favorable banking conditions could be more difficult to manage, given current daylight credit policies. Keywords: central bank, Federal Reserve, monetary policy, discount window, payment system, September 11, banking crises, daylight credit. † Prepared for the Carnegie-Rochester Conference on Public Policy, November 21-22, 2003. Exceptional research assistance was provided by Hoossam Malek, Christian Pascasio, and Jeff Kelley. I have benefited from helpful conversations with Marvin Goodfriend, who suggested this topic, David Duttenhofer, Spence Hilton, Sandy Krieger, Helen Mucciolo, John Partlan, Larry Sweet, and Jack Walton, and helpful comments from Stacy Coleman, Connie Horsley, and Brian Madigan. -

Rebuilding the Trade Center

Rebuilding the Trade Center An Interview with Larry A. Silverstein, President and Chief Executive Offi cer, Silverstein Properties, Inc. EDITORS’ NOTE In July 2001, Larry The progress at the Trade Center Silverstein completed the largest real site for many years was very slow. I estate transaction in New York his- was frustrated because I was able to tory when he signed a 99-year lease build 7 World Trade Center in a four- on the 10.6-million-square-foot World year time frame. Trade Center for $3.25 billion only to We went into the ground in 2002, see it destroyed in terrorist attacks six and by 2006, we fi nished it after every- weeks later on September 11, 2001. body had predicted that the building He is currently rebuilding the offi ce would never succeed. We fi nanced it component of the World Trade Center for 40 years. We leased it and today, site, a $7-billion project. Silverstein it’s over 90 percent rented. The build- owns and manages 120 Broadway, ing has been enormously successful. tenancies that have the capacity of occupying 120 Wall Street, 529 Fifth Avenue, Larry A. Silverstein (above); The sad thing is that with the bal- its entirety. So that is gratifying, especially since and 570 Seventh Avenue. In 2008, the World Trade Center ance of the site, we could have done that building is based upon the need of a tenant. Silverstein announced an agree- rendering (right) what we did on 7 if given the opportu- We have the same level of interest in Tower ment with Four Seasons Hotels and nity to do so. -

Daily Unemployment Compensation Data

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA DOES DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF DAILY UNEMPLOYMENT EMPLOYMENT SERVICES COMPENSATION DATA Preliminary numbers as of March 4, 2021.* Telephone Date Online Claims Daily Total Running Total Claims March 13, 2020 310 105 415 415 March 14, 2020 213 213 628 March 15, 2020 410 410 1,038 March 16, 2020 1,599 158 1,757 2,795 March 17, 2020 2,541 219 2,760 5,555 March 18, 2020 2,740 187 2,927 8,482 March 19, 2020 2,586 216 2,802 11,284 March 20, 2020 2,726 205 2,931 14,215 March 21, 2020 1,466 1,466 15,681 March 22, 2020 1,240 1,240 16,921 March 23, 2020 2,516 296 2,812 19,733 March 24, 2020 2,156 236 2.392 22,125 March 25, 2020 2,684 176 2,860 24,985 March 26, 2020 2,842 148 2,990 27,975 March 27, 2020 2,642 157 2,799 30,774 March 28, 2020 1,666 25 1,691 32,465 March 29, 2020 1,547 1,547 34,012 March 30, 2020 2,831 186 3,017 37,029 March, 31, 2020 2,878 186 3,064 40,093 April 1, 2020 2,569 186 2,765 42,858 April 2, 2020 2,499 150 2,649 45,507 April 3, 2020 2,071 300 2,371 47,878 April 4, 2020 1,067 14 1,081 48,959 April 5, 2020 1,020 1,020 49,979 April 6, 2020 2,098 155 2,253 52,232 April 7, 2020 1,642 143 1,715 54,017 April 8, 2020 1,486 142 1,628 55,645 *Recalculated and updated daily DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Telephone DODISTRICT OF CEOLUMBIASDate Online Claims Daily Total Running Total DEPARTMENT OF DAILY UNEMPLOYMENTClaims EMPLOYMENT SERVICES April 9, 2020 1,604 111 1,715 57,360 April 10, 2020 COMPENSATION1,461 119 1,580 DATA58,940 April 11, 2020 763 14 777 59,717 April 12, 2020 698 698 60,415 April 13, 2020 1,499 104 -

Pricing*, Pool and Payment** Due Dates January - December 2021 Mideast Marketing Area Federal Order No

Pricing*, Pool and Payment** Due Dates January - December 2021 Mideast Marketing Area Federal Order No. 33 Class & Market Administrator Payment Dates for Producer Milk Component Final Pool Producer Advance Prices Payment Dates Final Payment Due Partial Payment Due Pool Month Prices Release Date Payrolls Due & Pricing Factors PSF, Admin., MS Cooperative Nonmember Cooperative Nonmember January February 3 * February 13 February 22 December 23, 2020 February 16 ** February 16 February 17 Janaury 25 January 26 February March 3 * March 13 March 22 January 21 * March 15 March 16 March 17 February 25 February 26 March March 31 * April 13 April 22 February 18 * April 15 April 16 April 19 ** March 25 March 26 April May 5 May 13 May 22 March 17 * May 17 ** May 17 ** May 17 April 26 ** April 26 May June 3 * June 13 June 22 April 21 * June 15 June 16 June 17 May 25 May 26 June June 30 * July 13 July 22 May 19 * July 15 July 16 July 19 ** June 25 June 28 ** July August 4 * August 13 August 22 June 23 August 16 ** August 16 August 17 July 26 ** July 26 August September 1 * September 13 September 22 July 21 * September 15 September 16 September 17 August 25 August 26 September September 29 * October 13 October 22 August 18 * October 15 October 18 ** October 18 ** September 27 ** September 27 ** October November 3 * November 13 November 22 September 22 * November 15 November 16 November 17 October 25 October 26 November December 1 * December 13 December 22 October 20 * December 15 December 16 December 17 November 26 ** November 26 December January 5, 2022 January 13, 2022 January 22, 2022 November 17 * January 18, 2022 ** January 18, 2022 ** January 18, 2022 ** December 27 ** December 27 ** * If the release date does not fall on the 5th (Class & Component Prices) or 23rd (Advance Prices & Pricing Factors), the most current release preceding will be used in the price calculation. -

Academic Calendar

Academic Calendar 2018 – 2019 Academic Year Dallas Fall 2018: August 27, 2018 – December 16, 2018 EVENT DATE NOTES First Day of Instruction August 27, 2018 Week 1 of Fall Last Day to Add Courses September 2, 2018 End of Week 1 Labor Day September 3, 2018 Holiday Last Day to Drop with a “W” October 21, 2018 End of Week 8 Spring 2019 Schedule Preview October 22, 2018 Spring 2019 Registration October 29, 2018 Veterans Day (Observed) November 12, 2018 Holiday Thanksgiving Holiday November 22 - 23, 2018 Holiday Last Day of Instruction December 3, 2018 Week 15 Grades Due December 11, 2018 Official End of Semester December 16, 2018 Spring 2019: January 7, 2019 – April 28, 2019 First Day of Instruction January 7, 2019 Week 1 of Spring Last Day to Add Courses January 13, 2019 End of Week 1 Martin Luther King Jr Day January 21, 2019 Holiday Last Day to Drop with a “W” March 3, 2019 End of Week 8 Summer 2019 Schedule Preview March 4, 2019 Summer 2019 Registration March 11, 2019 Last Day of Instruction April 15, 2019 Week 15 Grades Due April 23, 2019 Official End of Semester April 28, 2019 Summer 2019: May 6, 2019 – August 25, 2019 All Programs: 8 Week Courses First Day of Instruction May 6, 2019 Week 1 of Summer Last Day to Add Courses May 12, 2019 End of Week 1 Memorial Day May 27, 2019 Holiday Fall 2019 Schedule Preview June 3, 2019 Last Day to Drop with a “W” June 9, 2019 End of Week 5 Fall 2019 Registration Begins June 10, 2019 Last Day of Instruction June 30, 2019 End of Week 8 Independence Day July 4, 2019 Holiday Grades Due July 8, 2019 Official End of Semester August 25, 2019 Dates subject to change. -

2021-2022 Custom & Standard Information Due Dates

2021-2022 CUSTOM & STANDARD INFORMATION DUE DATES Desired Cover All Desired Cover All Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due May 31 No Deliveries No Deliveries July 19 April 12 May 10 June 1 February 23 March 23 July 20 April 13 May 11 June 2 February 24 March 24 July 21 April 14 May 12 June 3 February 25 March 25 July 22 April 15 May 13 June 4 February 26 March 26 July 23 April 16 May 14 June 7 March 1 March 29 July 26 April 19 May 17 June 8 March 2 March 30 July 27 April 20 May 18 June 9 March 3 March 31 July 28 April 21 May 19 June 10 March 4 April 1 July 29 April 22 May 20 June 11 March 5 April 2 July 30 April 23 May 21 June 14 March 8 April 5 August 2 April 26 May 24 June 15 March 9 April 6 August 3 April 27 May 25 June 16 March 10 April 7 August 4 April 28 May 26 June 17 March 11 April 8 August 5 April 29 May 27 June 18 March 12 April 9 August 6 April 30 May 28 June 21 March 15 April 12 August 9 May 3 May 28 June 22 March 16 April 13 August 10 May 4 June 1 June 23 March 17 April 14 August 11 May 5 June 2 June 24 March 18 April 15 August 12 May 6 June 3 June 25 March 19 April 16 August 13 May 7 June 4 June 28 March 22 April 19 August 16 May 10 June 7 June 29 March 23 April 20 August 17 May 11 June 8 June 30 March 24 April 21 August 18 May 12 June 9 July 1 March 25 April 22 August 19 May 13 June 10 July 2 March 26 April 23 August 20 May 14 June 11 July 5 March 29 April 26 August 23 May 17 June 14 July 6 March 30 April 27 August 24 May 18 June 15 July 7 March 31 April 28 August 25 May 19 June 16 July 8 April 1 April 29 August 26 May 20 June 17 July 9 April 2 April 30 August 27 May 21 June 18 July 12 April 5 May 3 August 30 May 24 June 21 July 13 April 6 May 4 August 31 May 25 June 22 July 14 April 7 May 5 September 1 May 26 June 23 July 15 April 8 May 6 September 2 May 27 June 24 July 16 April 9 May 7 September 3 May 28 June 25. -

Division of Personnel Employee Information and Payroll Audit Section

Division of Personnel Employee Information and Payroll Audit Section This document is provided as a service to state agencies. Note: The 90-day interval includes both the beginning and ending dates. 90-DAY INTERVAL CALENDAR FOR 2011 JANUARY 2011 If the date is... 90th weekday after the date is... JANUARY 3 MONDAY MAY 6 FRIDAY JANUARY 4 TUESDAY MAY 9 MONDAY JANUARY 5 WEDNESDAY MAY 10 TUESDAY JANUARY 6 THURSDAY MAY 11 WEDNESDAY JANUARY 7 FRIDAY MAY 12 THURSDAY JANUARY 10 MONDAY MAY 13 FRIDAY JANUARY 11 TUESDAY MAY 16 MONDAY JANUARY 12 WEDNESDAY MAY 17 TUESDAY JANUARY 13 THURSDAY MAY 18 WEDNESDAY JANUARY 14 FRIDAY MAY 19 THURSDAY JANUARY 17 MONDAY MAY 20 FRIDAY JANUARY 18 TUESDAY MAY 23 MONDAY JANUARY 19 WEDNESDAY MAY 24 TUESDAY JANUARY 20 THURSDAY MAY 25 WEDNESDAY JANUARY 21 FRIDAY MAY 26 THURSDAY JANUARY 24 MONDAY MAY 27 FRIDAY JANUARY 25 TUESDAY MAY 30 MONDAY JANUARY 26 WEDNESDAY MAY 31 TUESDAY JANUARY 27 THURSDAY JUNE 1 '11 WEDNESDAY JANUARY 28 FRIDAY JUNE 2 THURSDAY JANUARY 31 MONDAY JUNE 3 FRIDAY FEBRUARY 2011 If the date is... 90th weekday after the date is... FEBRUARY 1 TUESDAY JUNE 6 MONDAY FEBRUARY 2 WEDNESDAY JUNE 7 TUESDAY FEBRUARY 3 THURSDAY JUNE 8 WEDNESDAY FEBRUARY 4 FRIDAY JUNE 9 THURSDAY FEBRUARY 7 MONDAY JUNE 10 FRIDAY FEBRUARY 8 TUESDAY JUNE 13 MONDAY FEBRUARY 9 WEDNESDAY JUNE 14 TUESDAY FEBRUARY 10 THURSDAY JUNE 15 WEDNESDAY FEBRUARY 11 FRIDAY JUNE 16 THURSDAY FEBRUARY 14 MONDAY JUNE 17 FRIDAY FEBRUARY 15 TUESDAY JUNE 20 MONDAY FEBRUARY 16 WEDNESDAY JUNE 21 TUESDAY FEBRUARY 17 THURSDAY JUNE 22 WEDNESDAY FEBRUARY 18 FRIDAY JUNE 23 THURSDAY FEBRUARY 21 MONDAY JUNE 24 FRIDAY FEBRUARY 22 TUESDAY JUNE 27 MONDAY FEBRUARY 23 WEDNESDAY JUNE 28 TUESDAY FEBRUARY 24 THURSDAY JUNE 29 WEDNESDAY FEBRUARY 25 FRIDAY JUNE 30 THURSDAY FEBRUARY 28 MONDAY JULY 1 '11 FRIDAY MARCH 2011 If the date is.. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

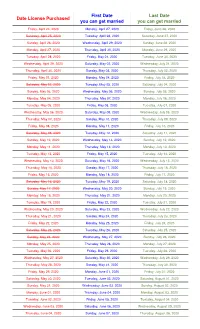

Marriage Valid Dates

First Date Last Date Date License Purchased you can get married you can get married Friday, April 24, 2020 Monday, April 27, 2020 Friday, June 26, 2020 Saturday, April 25, 2020 Tuesday, April 28, 2020 Saturday, June 27, 2020 Sunday, April 26, 2020 Wednesday, April 29, 2020 Sunday, June 28, 2020 Monday, April 27, 2020 Thursday, April 30, 2020 Monday, June 29, 2020 Tuesday, April 28, 2020 Friday, May 01, 2020 Tuesday, June 30, 2020 Wednesday, April 29, 2020 Saturday, May 02, 2020 Wednesday, July 01, 2020 Thursday, April 30, 2020 Sunday, May 03, 2020 Thursday, July 02, 2020 Friday, May 01, 2020 Monday, May 04, 2020 Friday, July 03, 2020 Saturday, May 02, 2020 Tuesday, May 05, 2020 Saturday, July 04, 2020 Sunday, May 03, 2020 Wednesday, May 06, 2020 Sunday, July 05, 2020 Monday, May 04, 2020 Thursday, May 07, 2020 Monday, July 06, 2020 Tuesday, May 05, 2020 Friday, May 08, 2020 Tuesday, July 07, 2020 Wednesday, May 06, 2020 Saturday, May 09, 2020 Wednesday, July 08, 2020 Thursday, May 07, 2020 Sunday, May 10, 2020 Thursday, July 09, 2020 Friday, May 08, 2020 Monday, May 11, 2020 Friday, July 10, 2020 Saturday, May 09, 2020 Tuesday, May 12, 2020 Saturday, July 11, 2020 Sunday, May 10, 2020 Wednesday, May 13, 2020 Sunday, July 12, 2020 Monday, May 11, 2020 Thursday, May 14, 2020 Monday, July 13, 2020 Tuesday, May 12, 2020 Friday, May 15, 2020 Tuesday, July 14, 2020 Wednesday, May 13, 2020 Saturday, May 16, 2020 Wednesday, July 15, 2020 Thursday, May 14, 2020 Sunday, May 17, 2020 Thursday, July 16, 2020 Friday, May 15, 2020 Monday, May 18, 2020 -

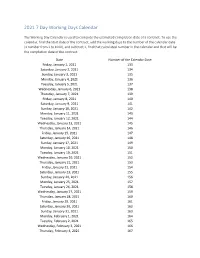

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

Financing Affordable Rental Housing: Defining Success Five Case Studies

Financing Affordable Rental Housing: Defining Success Five Case Studies Bessy M. Kong and Derek Hsiang Financing Affordable Rental Housing: Defining Success Five Case Studies Bessy: Defining M. Kong and Derek Hsiang Success Five Case Studies ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was produced with the support and collaboration of the Korea Housing and Urban Guarantee Corporation (HUG) as a part of a joint research initiative with the Urban Sustainability Lab- oratory of the Wilson Center to examine public finance programs to increase the supply of affordable rental housing in the United States and Korea. The authors would like to thank HUG leadership and research partners, including Sung Woo Kim, author of the Korean report, and Dongsik Cho, for his support of the HUG-Wilson Center part- nership. We would also like to thank Michael Liu, Director of the Miami-Dade County Department of Public Housing and Commu- nity Development, for sharing his knowledge and expertise to in- form this research and for presenting the work in a research sem- inar and exchange in Seoul in November 2016. We are grateful to Alven Lam, Director of International Markets, Office of Capital Market at GinnieMae, for providing critical guidance for this joint research initiative and for his contribution to the Seoul seminar. Thanks to those who provided information for the case studies: Jorge Cibran and José A. Rodriguez (Collins Park); Andrew Gross and Michael Miller (Skyline Village); and, Robert Bernardin and Marianne McDermott (Pond View Village). A special acknowl- edgement to Allison Garland who read all the drafts; to Marina Kurokawa who helped with the initial research; and to Wallah Elshekh and Carly Giddings who assisted in proof reading and the formatting of the bibliography, footnotes and appendices. -

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project Lynne B. Sagalyn THREE YEARS after the terrorist attack of September 11,2001, plans for four key elements in rebuilding the World Trade Center (WC) site had been adopted: restoring the historic streetscape, creating a new public transportation gate- way, building an iconic skyscraper, and fashioning the 9/11 memorial. Despite this progress, however, what ultimately emerges from this heavily argued deci- sionmakmg process will depend on numerous design decisions, financial calls, and technical executions of conceptual plans-or indeed, the rebuilding plan may be redefined without regard to plans adopted through 2004. These imple- mentation decisions will determine whether new cultural attractions revitalize lower Manhattan and whether costly new transportation investments link it more directly with Long Island's commuters. These decisions will determine whether planned open spaces come about, and market forces will determine how many office towers rise on the site. In other words, a vision has been stated, but it will take at least a decade to weave its fabric. It has been a formidable challenge for a city known for its intense and frac- tious development politics to get this far. This chapter reviews the emotionally charged planning for the redevelopment of the WTC site between September 2001 and the end of 2004. Though we do not yet know how these plans will be reahzed, we can nonetheless examine how the initial plans emerged-or were extracted-from competing ambitions, contentious turf battles, intense architectural fights, and seemingly unresolvable design conflicts. World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project 25 24 Contentious City ( rebuilding the site.