Inside the Camera Obscura – Optics and Art Under the Spell of the Projected Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Setting up the Palette by Carole Greene

Setting Up the Palette by Carole Greene De Anza College Cupertino, California Manuscript Preparation: D’Artagnan Greene Cover Photo: Hotel Johannes Vermeer Restaurant, Delft, Holland © 2002 by Bill Greene ii Copyright © 2002 by Carole Greene ISBN X-XXXX-XXXX-X All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever, by photography or xerography or by any other means, by broadcast or transmission, by translation into any kind of language, nor by recording electronically or otherwise, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in critical articles or reviews. Printed in the United States of America. X X X X X X X X X X Address orders to: XXXXXXXXXXX 1111 XXXX XX XXXXXX, XX 00000-0000 Telephone 000-000-0000 Fax 000-000-0000 XXXXX Publishing XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX iii TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ix CHAPTER 1- Mastering the Tools 1 An Overview 3 The Clause 15 The Simple Sentence 17 The Verb Check 21 Items in a Series 23 Inverted Clauses and Questions 29 Analyzing a Question 33 Exercise 1: Locate Subjects and Verbs in Questions 35 Exercise 2: Locate Verbs in Simple Sentences 37 Exercise 3: Locate Subjects in Simple Sentences 47 Exercise 4: Locate Subjects and Verbs in Simple Sentences 55 iv The Need to Change Reading Habits 69 The Phrase 71 A Phrase Versus a Clause 73 Prepositional Phrases 75 Common Single Word Prepositions 77 Group Prepositions 78 Developing a Memory System 79 Memory Facts 81 Analyzing the Function of Prepositional Phrases 83 Exercise 5: Locating -

Gallery Text That Accompanies This Exhibition In

Steeped in the classical training of an English gentleman, Edward Dodwell (1777/78– 1832) first traveled through Greece in 1801. He returned in 1805 in the company of an Italian artist, Simone Pomardi (1757–1830), and together they toured the country for fourteen months, drawing and documenting the landscape with exacting detail. They produced around a thousand illustrations, most of which are now in the collection of the Packard Humanities Institute in Los Altos, California. A selection from this rich archive is presented here for the first time in the United States. Dodwell and Pomardi frequently used a camera obscura, an optical device that made it easier to create accurate images. Beyond providing evidence for the appearance of monuments and vistas, their illustrations manifest the ideal of the picturesque that enraptured so many European travelers. The sight of ancient temples lying in ruin, or of the Greek people under Turkish rule as part of the Ottoman Empire, prompted meditation on the transience of human accomplishments. As Dodwell himself wrote: “When we contemplated the scene around us, and beheld the sites of ruined states, and kingdoms, and cities, which were once elevated to a high pitch of prosperity and renown, but which have now vanished like a dream . we could not but forcibly feel that nations perish as well as individuals.” Dodwell’s own words accompany the majority of images in this exhibition. His descriptions are drawn from his Classical and Topographical Tour through Greece, during the Years 1801, 1805, and 1806 (London, 1819). The author’s original spelling, capitalization, and punctuation have been retained. -

Elements of Screenology: Toward an Archaeology of the Screen 2006

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Erkki Huhtamo Elements of screenology: Toward an Archaeology of the Screen 2006 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1958 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Huhtamo, Erkki: Elements of screenology: Toward an Archaeology of the Screen. In: Navigationen - Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturwissenschaften, Jg. 6 (2006), Nr. 2, S. 31–64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1958. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

The Spectrumspectrum the Calendar 2 Membership Corner 3 the Newsletter for the Buffalo Astronomical a Letter from Mike 4

Inside this issue: TheThe SpectrumSpectrum The Calendar 2 Membership Corner 3 The Newsletter for the Buffalo Astronomical A Letter from Mike 4 Obs Report 5 The Banquet 6 Stay Warm and 9 Cozy Astro Day Poster 11 March/April The Galileo Affair 12 Volume 17, Issue 2 Gallery 18 May Star Chart 19 March Star Chart 19 April Star Chart 20 Our Newly Redesigned Website is Live! If you haven’t checked out BuffaloAstronomy.com recently, it’s time for a visit. Our new site, designed by webmaster and club member Gene Timothy is up and running. The interface is clean and organized and much easier to update with club news and astronomy content. You can now register for the April Banquet, join the club and pay dues using a PayPal account or a major credit card. Coming soon is a new log-in area which will allow members to communicate with each other, share a profile and access special features, including BAA historical information and an archive of Spectrum issues dating back many decades. Come visit and share your comments, thoughts and ideas on how we can make the site better and more useful to the club. A BIG thank you to Gene and the BAA Board for their hard work and creativity! 1 BAA Schedule of Astronomy Fun for 2015 BAA Schedule of Astronomy Fun for 2015 Mar 13: BAA Meeting at 7:30pm at Buffalo State College Mar 20: New Moon Mar 20: Total Solar Eclipse (Arctic) Mar 21-22: Maple Syrup Festival at BMO 9am-3pm Need help for Solar viewing Mar 21: Messier Marathon Dusk till Dawn at Beaver Meadow Observatory Apr 4: First Public Night at Beaver Meadow Observatory April 4: Total Lunar Eclipse Apr 11: BAA Annual Dinner Meeting at Risottos April 18; New Moon Apr 18/19: NEAF who wants to car pool?? April 21-22: Lyrids Meteor Shower Apr 25: Astronomy Day at Buffalo Museum of Science details TBA May 2: Public Night BMO May 8: BAA Meeting at 7:30pm at Buffalo State College May 18: New Moon Jun 6: Public Night BMO Jun 12: BAA Meeting/Elections at 7:30pm at Buffalo State College Jun 17 New Moon July 4: Public Night BMO – I will need help as I have family obligations that day. -

Technologies of Expression, Originality and the Techniques of the Observer

Technologies of Expression, Originality and the Techniques of the Observer A dissertation presented in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Art and Design at the Art and Design Faculty of the Bauhaus University Weimar By Mirette Bakir Born on 16.12.1980 Matriculation Nº 90498 2014 Defended on 22.04.2015 Supervisors: 1. Prof. Dr. phil. habil. Frank Hartmann Faculty of Art and Design, Bauhaus University – Weimar 2. Prof. Dr. Abobakr El Nawawy Faculty of Applied Arts, Helwan University – Cairo 1 To Ziad 2 Contents Part 1 (Theoretical Work) .............................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ......................................................................................... 6 2. The observer: ..................................................................................... 12 2.1. Preface .................................................................................................... 12 2.2. The Nineteenth Century ...................................................................... 13 2.3. Variations of the Observer’s Perception ........................................... 20 2.4. The Antinomies of Observation ......................................................... 20 3. Science, Art, Technology and Linear Perspective ........................ 25 3.1. The Linear Perspective ........................................................................ 27 3.2. Linear perspective in use ................................................................... -

The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Author(S): Nicholas Overgaard Source: Prandium - the Journal of Historical Studies, Vol

Early Modern Catholic Defense of Copernicanism: The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Author(s): Nicholas Overgaard Source: Prandium - The Journal of Historical Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Spring, 2013), pp. 29-36 Published by: The Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto Mississauga Stable URL: http://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/prandium/article/view/19654 Prandium: The Journal of Historical Studies Vol. 2, No. 1, (2013) Early Modern Catholic Defense of Copernicanism: The Jesuits and the Galileo Affair Nicholas Overgaard “Obedience should be blind and prompt,” Ignatius of Loyola reminded his Jesuit brothers a decade after their founding in 1540.1 By the turn of the seventeenth century, the incumbent Superior General Claudio Aquaviva had reiterated Loyola’s expectation of “blind obedience,” with specific regard to Jesuit support for the Catholic Church during the Galileo Affair.2 Interpreting the relationship between the Jesuits and Copernicans like Galileo Galilei through the frame of “blind obedience” reaffirms the conservative image of the Catholic Church – to which the Jesuits owed such obedience – as committed to its medieval traditions. In opposition to this perspective, I will argue that the Jesuits involved in the Galileo Affair3 represent the progressive ideas of the Church in the early seventeenth century. To prove this, I will argue that although the Jesuits rejected the epistemological claims of Copernicanism, they found it beneficial in its practical applications. The desire to solidify their status as the intellectual elites of the Church caused the Jesuits to reject Copernicanism in public. However, they promoted an intellectual environment in which Copernican studies – particularly those of Galileo – could develop with minimal opposition, theological or otherwise. -

“Cornelis Drebbel (Alkmaar 1572 – Londen 1633): Kloeck Verstant, Een Pronck Der Wereldt”

Histechnica – Vereniging Vrienden van KIVI – het Academisch Erfgoed van de TU Delft Afdeling Geschiedenis der Techniek Programma commissaris: dr.ir. P.Th.L.M. van Woerkom, tel. 070 – 30 70 275, e-mail [email protected] Secretaris Histechnica: ir. H. Boonstra, tel. 070 – 38 73 808, e-mail [email protected] Secretaris KIVI afd. Geschiedenis der Techniek: ir. A. de Liefde, tel. 070 – 39 66 999, e-mail [email protected] Delft, 10 maart 2019 Geachte leden, De besturen van de vereniging Histechnica en van de KIVI afdeling Geschiedenis der Techniek hebben het genoegen u uit te nodigen tot het bijwonen van een voordracht te houden door de heer H. van Onna, met titel: “Cornelis Drebbel (Alkmaar 1572 – Londen 1633): Kloeck Verstant, een pronck der Wereldt” > Datum: zaterdag 13 april 2019. > Plaats: Science Centre van de TU Delft, Mijnbouwstraat 120, 2628 RX Delft. > Programma: 10.00 uur: Gebouw open; ontvangst met koffie 10.10 uur: Algemene Leden Vergadering van leden van de vereniging Histechnica gevolgd door: 11:00 uur: Voordracht door de heer H. van Onna (Tweede Drebbel Genootschap). 11:45 uur: Pauze. 12:15 uur: Vervolg van voordracht / afsluitende discussie. 12:45 uur: Einde bijeenkomst. U bent met uw introducé’s van harte welkom. Aan het bijwonen van de voordracht zijn geen kosten verbonden. U wordt vriendelijk verzocht zich tevoren aan te melden, uiterlijk zaterdag 6 april 2019. > Hoe aanmelden: - leden van KIVI : aanmelden via de KIVI website (www.kivi.nl) - leden van Histechnica : aanmelden via [email protected] Zaterdag 13 april 2019 > Samenvatting van de voordracht Vandaag vertel ik u over het Cornelis Drebbel, natuurfilosoof en inventor, ‘de Edison in zijn tijd’. -

Words of Thanks by Dan Sapone

Words of Thanks By Dan Sapone “And yet it moves" (in the original Italian: “Eppur si muove”) — Galileo Galilei, Gentleman of Florence = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = "The Sun, with all its planets revolving around it and depending upon it, still can find the time to ripen a bunch of grapes as if it had nothing else in the universe to do." — Galileo Galilei, 1632 This line first captured my imagination when I saw it on the back label of a bottle of red wine (where else would I look for memorable, meaningful words, eh?). I was looking for some wine for our Thanksgiving dinner table, the family was going to be there, and I would be offering a Thanksgiving Toast — I thought these words were perfect. When the time came, with the bottle in my hand I mentioned that we all have so much to be thankful for: our families, our homes, the work we do, the people who are kind to us, the food and wine we enjoy, and the good times we have. Then, using Galileo’s words, I gave thanks for The Sun, representing all of the ‘greater powers’ that contribute to all of that goodness — whatever and whomever they might be. The words were fun, appropriate to the occasion, and they brought smiles. We lifted our glasses and said “Thanks’ to each other. Galileo’s words helped us do that. A Random Bunch of Thanksgiving Photos “And yet it moves.” Thanksgiving, 2017 Page 1 of 4 Galileo’s Words In Context So, if we let our minds drift back 385 years to Galileo’s time, we learn that he caused quite a kerfuffle, to say the least, when he first used these words. -

Augustus II the Strong's Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches

Augustus II the Strong’s Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches Palais zu Dresden: A Visual Demonstration of Power and Splendor Zifeng Zhao Department of Art History & Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal September 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Zifeng Zhao 2018 i Abstract In this thesis, I examine Augustus II the Strong’s porcelain collection in the Japanisches Palais, an 18th-century Dresden palace that housed porcelains collected from China and Japan together with works made in his own Meissen manufactory. I argue that the ruler intended to create a social and ceremonial space in the chinoiserie style palace, where he used a systematic arrangement of the porcelains to demonstrate his kingly power as the new ruler of Saxony and Poland. I claim that such arrangement, through which porcelains were organized according to their colors and styles, provided Augustus II’s guests with a designated ceremonial experience that played a significant role in the demonstration of the King’s political and financial prowess. By applying Gérard de Lairesse’s color theory and Samuel Wittwer’s theory of “the phenomenon of sheen” to my analysis of the arrangement, I examine the ceremonial functions of such experience. In doing so, I explore the three unique features of porcelain’s materiality—two- layeredness, translucency and sheen. To conclude, I argue that the secrecy of the technology of porcelain’s production was the key factor that enabled Augustus II’s demonstration of power. À travers cette thèse, j'examine la collection de porcelaines d'Auguste II « le Fort » au Palais Japonais, un palais à Dresde du 18ème siècle qui abritait des porcelaines provenant de Chine, du Japon et de sa propre manufacture à Meissen. -

Interiors and Interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism

ARTICLE Received 20 Feb 2017 | Accepted 11 May 2017 | Published 12 Jul 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 OPEN Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism Benjamin Binstock1 ABSTRACT Johannes Vermeer may well be the foremost painter of interiors and interiority in the history of art, yet we have not necessarily understood his achievement in either domain, or their relation within his complex development. This essay explains how Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and used his family members as models, combining empiricism and subjectivity. Vermeer was exceptionally self-conscious and sophisticated about his artistic task, which we are still laboring to understand and articulate. He eschewed anecdotal narratives and presented his models as models in “studio” settings, in paintings about paintings, or art about art, a form of modernism. In contrast to the prevailing con- ception in scholarship of Dutch Golden Age paintings as providing didactic or moralizing messages for their pre-modern audiences, we glimpse in Vermeer’s paintings an anticipation of our own modern understanding of art. This article is published as part of a collection on interiorities. 1 School of History and Social Sciences, Cooper Union, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: (e-mail: [email protected]) PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:17068 | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 | www.palgrave-journals.com/palcomms 1 ARTICLE PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 ‘All the beautifully furnished rooms, carefully designed within his complex development. This essay explains how interiors, everything so controlled; There wasn’t any room Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and his for any real feelings between any of us’. -

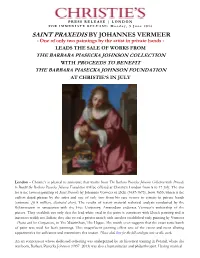

SAINT PRAXEDIS by JOHANNES VERMEER - One of Only Two Paintings by the Artist in Private Hands

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Monday, 9 June 2014 SAINT PRAXEDIS BY JOHANNES VERMEER - One of only two paintings by the artist in private hands - LEADS THE SALE OF WORKS FROM THE BARBARA PIASECKA JOHNSON COLLECTION WITH PROCEEDS TO BENEFIT THE BARBARA PIASECKA JOHNSON FOUNDATION AT CHRISTIE’S IN JULY London – Christie’s is pleased to announce that works from The Barbara Piasecka Johnson Collection with Proceeds to Benefit the Barbara Piasecka Johnson Foundation will be offered at Christie’s London from 8 to 17 July. The star lot is the famous painting of Saint Praxedis by Johannes Vermeer of Delft (1632-1675), from 1655, which is the earliest dated picture by the artist and one of only two from his rare oeuvre to remain in private hands (estimate: £6-8 million, illustrated above). The results of recent material technical analysis conducted by the Rijksmuseum in association with the Free University, Amsterdam endorses Vermeer’s authorship of the picture. They establish not only that the lead white used in the paint is consistent with Dutch painting and is incontrovertibly not Italian; they also reveal a precise match with another established early painting by Vermeer - Diana and her Companions, in The Mauritshuis, The Hague. The match even suggests that the exact same batch of paint was used for both paintings. This magnificent painting offers one of the rarest and most alluring opportunities for collectors and institutions this season. Please click here for the full catalogue note on this work. An art connoisseur whose dedicated collecting was underpinned by art historical training in Poland, where she was born, Barbara Piasecka Johnson (1937- 2013) was also a humanitarian and philanthropist. -

Sources: Galileo's Correspondence

Sources: Galileo’s Correspondence Notes on the Translations The following collection of letters is the result of a selection made by the author from the correspondence of Galileo published by Antonio Favaro in his Le opere di Galileo Galilei,theEdizione Nazionale (EN), the second edition of which was published in 1968. These letters have been selected for their relevance to the inves- tigation of Galileo’s practical activities.1 The information they contain, moreover, often refers to subjects that are completely absent in Galileo’s publications. All of the letters selected are quoted in the work. The passages of the letters, which are quoted in the work, are set in italics here. Given the particular relevance of these letters, they have been translated into English for the first time by the author. This will provide the international reader with the opportunity to achieve a deeper comprehension of the work on the basis of the sources. The translation in itself, however, does not aim to produce a text that is easily read by a modern reader. The aim is to present an understandable English text that remains as close as possible to the original. The hope is that the evident disadvantage of having, for example, long and involute sentences using obsolete words is compensated by the fact that this sort of translation reduces to a minimum the integration of the interpretation of the translator into the English text. 1Another series of letters selected from Galileo’s correspondence and relevant to Galileo’s practical activities and, in particular, as a bell caster is published appended to Valleriani (2008).