Richard Foreman Is Angry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YALE-NUS SYLLABUS for AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE THEATER of the 1960’S and 1970’S

YALE-NUS SYLLABUS FOR AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE THEATER OF THE 1960’s AND 1970’s YHU 3304, Spring semester, 2019 Mondays and Thursdays, 9am-10:30am Room Y-CR9 Professor Joan MacIntosh [email protected] Office hours by appointment only, Mondays, after class. Additionally, there will be a mid-semester conference with each student and an end-of-the-year conference with each student, to give and receive feedback. These will be scheduled within the semester time, and will not infringe on either the Spring Break or the end of the year Reading Period. COURSE OVERVIEW This seminar course will explore the American Avant-Garde Theatre of the 1960’s and 1970’s, and its enduring significance. It will include an examination of the political, social, economic, and aesthetic events that led to its beginnings, and will follow the journey of its passionate creativity and diversity of expression, as well as the political upheavals and the cultural revolution that were inextricably a part of it. Readings will include the work of Gertrude Stein, Allen Ginsberg, The Living Theatre, The Open Theater, The Performance Group, Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Company, Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company, Mabou Mines, and others. We will also read 1968, Environmental Theatre, Be Here Now, Towards a Poor Theatre, and selected historical overviews. We will explore each group’s vision, body of work, dynamics, and relation and significance to their world. In line with this, students will write about these theatre companies, and create their own live performances and work, based on the readings, possible films, and discussions. -

Prof. Siemund

Veranstalter: Dennis Büscher-Ulbrich Off-Off-Broadway and Beyond: Experimental Theatre Thema: and Avant-Garde Performance 1945–1970 [AA-A3, ENG-7, AA-W] Art der Veranstaltung: Seminar Ib Veranstaltungsnummer: 53-561 Zeit: Mo 18-20 Raum: Phil 1269 Beginn: 17. Oktober 2011 Course Description: The early developing OFF-OFF- BROADWAY MOVEMENT of the 1950s and 1960s sought freedom from the various constraints — aesthetically and otherwise — of conventional theatre. Mainstream theatre at the time was dominated by the musical and the psycho- logical drama, spawning pro- ductions that were conceived as business ventures and, if successful, packaged and toured. The notion of theatre as a packaged commodity offended the avant-garde sensibilities of artists who observed the psycho- logical and physical constraints built within the theatrical space itself. Instead, they enthusi- astically turned to alternative sites and experimental forms, eventually collapsing the dis- tinction between theatre and PERFORMANCE ART. While con- ventional theatre taught the spectator to lose herself in the fictional onstage time, space, and characters, avant-garde theatre and performance relied on the spectator’s complete consciousness of the present, i.e. the real time and space shared by audience and performers. The primary importance of the spectator’s consciousness of the present is that she is an active force in creating the theatrical event rather than a passive observer of a ready-made production. To approach this phenomenon, we will be looking closely at three significant avant-garde moments in postwar American theatre and performance: THE LIVING THEATRE, HAPPENINGS/FLUXUS, and the BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT. We will analyze and discuss experimental plays that still work within the confines of theatrical space, like The Connection (1959) and Dutchman (1964), semi-improvisational and interactive plays, like Paradise Now (1967), as well as Happenings and other ‘far-out’ performances. -

Download Download

Teresa de Lauretis Futurism: A Postmodern View* The importance of Modernism and of the artistic movements of the first twenty or so years of this century need not be stressed. It is now widely acknowledged that the "historical avant-garde" was the crucible for most of the art forms and theories of art that made up the contemporary esthetic climate. This is evidenced, more than by the recently coined academic terms "neoavanguardia" and "postmodernism," 1 by objective trends in the culture of the last two decades: the demand for closer ties between artistic perfor- mance and real-life interaction, which presupposes a view of art as social communicative behavior; the antitraditionalist thrust toward interdisciplinary or even non-disciplinary academic curri- cula; the experimental character of all artistic production; the increased awareness of the material qualities of art and its depen- dence on physical and technological possibilities, on the one hand; on the other, its dependence on social conventions or semiotic codes that can be exposed, broken, rearranged, transformed. I think we can agree that the multi-directional thrust of the arts and their expansion to the social and the pragmatic domain, the attempts to break down distinctions between highbrow and popular art, the widening of the esthetic sphere to encompass an unprecedented range of phenomena, the sense of fast, continual movement in the culture, of rapid obsolescence and a potential transformability of forms are issues characteristic of our time. Many were already implicit, often explicit, in the project of the historical avant-garde. But whereas this connection has been established and pursued for Surrealism and Dada, for example, Italian Futurism has remained rather peripheral in the current reassessment; indeed one could say that it has been marginalized and effectively ignored. -

The-Vandal.Pdf

THE FLEA THEATER JIM SIMPSON artistic director CAROL OSTROW producing director BETH DEMBROW managing director presents the world premiere of THE VANDAL written by HAMISH LINKLATER directed by JIM SIMPSON DAVID M. BARBER set design BRIAN ALDOUS lighting design CLAUDIA BROWN costume design BRANDON WOLCOTT sound design and original music MICHELLE KELLEHER stage manager EDWARD HERMAN assistant stage manager CAST (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) Man...........................................................................................................................Zach Grenier Woman...............................................................................................................Deirdre O’Connell Boy...........................................................................................................................Noah Robbins CREATIVE TEAM Playwright...........................................................................................................Hamish Linklater Director.......................................................................................................................Jim Simpson Set Design..............................................................................................................David M. Barber Lighting Design.........................................................................................................Brian Aldous Costume Design......................................................................................................Claudia Brown Sound Design and Original -

Theatre & Performance

CONTEMPORARY Theatre & Performance MULTICULTURALISM/ DIVERSITY • African-American Theatre • Global Theatre • LGBTQ • Performance • Asian-American • Performance Art Theatre • Experimental Theatre • Latino Theatre (LATC) AFRICAN-AMERICAN THEATRE • August Wilson (1945-2005) - Fences (1987) • Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (1988) • The Piano Lesson (1990) ASIAN-AMERICAN THEATRE • East/West Players (downtown LA) • David Henry Huang - M. Butterfly, Bondage, Yellow Face LGBTQ • Charles Ludlam (19431987) died of AIDS— founded The Ridiculous Theatre Company- The Mystery of Irma Vep (1984) with Everett Quinton • Tony Kushner- Angels in America (1993) • Larry Kramer -The Normal Heart (1985) • Terence McNally - Mothers and Sons (2014) • Split Britches (WOW Cafe)- Beauty and The Beast (1982), Belle Reprieve (1990), Lesbians Who Kill (1992) • The Tectonic Theatre Company (The Laramie Project) • Rent, Hedwig and The Angry Inch, Kinky Boots, Fun Home LATINO THEATRE • LATC (Latino Theatre Company- LA Theatre Center)- founded 1985 by Artistic Director, Jose Luis Valenzuela • Zoot Suit (1979) by Luis Valdez- made into a film (1981) • based on the Sleepy Lagoon Murder Trial (1942) and the Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M51xwySGNYc https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dwINn5DEL1c GLOBAL THEATRE • Takarazuka Revue (Drag performance in Japan) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JLy2iOnBnsA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Wccu0JjcLw • Handspring Puppet Company (South Africa) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SqAkQCbuvqg • Chinese Performance (spectacle) -

La Constellation Tzadik : 20 Ans/20 Disques the Tzadik Constellation: 20 Years/20 Albums Pierre-Yves Macé, Giuseppe Frigeni Et David Konopnicki

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 08:11 Circuit Musiques contemporaines La constellation Tzadik : 20 ans/20 disques The Tzadik Constellation: 20 Years/20 Albums Pierre-Yves Macé, Giuseppe Frigeni et David Konopnicki Tzadik : l’esthétique discographique selon John Zorn Résumé de l'article Volume 25, numéro 3, 2015 Sous la forme d’une série de courtes chroniques, cette enquête propose un parcours subjectif à six mains à travers le catalogue de la maison de disques URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1034501ar Tzadik. Les trois auteurs, fervents « tzadikologues », ont sélectionné un disque DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1034501ar par année, depuis 1995 jusqu’à 2014, en veillant à ce que leur choix rende compte de la totalité des collections qui font la richesse unique de Tzadik Aller au sommaire du numéro (Composer Series, New Japan, Radical Jewish Culture, etc.). À travers les travaux de différents artistes de multiples horizons (Annie Gosfield, Pamelia Kurstin, Many Arms…), cette « constellation » guidera le lecteur à travers un dédale de genres et de sous-genres de l’underground musical (de la noise au Éditeur(s) postminimalisme, en passant par le klezmer, le dub et la fusion), tout en faisant Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal apparaître en creux la personnalité de John Zorn comme défricheur de talents sans frontières. ISSN 1183-1693 (imprimé) 1488-9692 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Macé, P.-Y., Frigeni, G. & Konopnicki, D. (2015). La constellation Tzadik : 20 ans/20 disques. Circuit, 25(3), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.7202/1034501ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2015 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. -

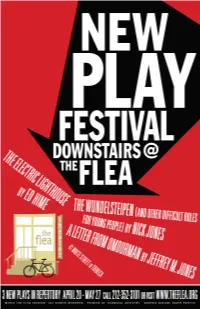

The Flea Theater

THE FLEA THEATER JIM SIMP S ON ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OS TROW PRODUCING DIRECTOR BETH DEM B ROW MANAGING DIRECTOR PRESENTS THE WORLD PREMIERE OF A LETTER FROM OMDURMAN WRITTEN BY JEFFREY M. JONE S DIRECTED BY PAGE BURKHOL D ER FEATURING HE AT S T B KATE SIN C LAIR FO S TER SET DESIGN JONATHAN COTTLE LIGHTING DESIGN WHITNEY LO C HER COSTUME DESIGN COLIN WHITELY SOUND DESIGN DAN DURKIN PROJECTION DESIGN JULON D RE BROWN STAGE MANAGMENT A LETTER FROM OMDURMAN CAST (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE ) Dave...............................................................................................................Matt Barbot Charlie..........................................................................................................Wilton Yeung Wyatt................................................................................................................Will Turner Josie........................................................................................................Veracity Butcher Understudies: Eric Folks (Wyatt), Danny Rivera (Charlie & Dave) CREATIVE TEAM Playwright.............................................................................................................Jeffrey M. Jones Director................................................................................................................Page Burkholder Set Design......................................................................................................Kate Sinclair Foster Lighting Design......................................................................................................Jonathan -

Itinera N. 3, 2012

Futurism and Experimentation in Italian Theater in the Late 20th Century di Alberto Bentoglio Abstract This paper aims to understand whether and to which extent the Futur- ism theory of theatre and its practices have influenced the Italian con- temporary scene. Common opinion still has it that Futurism has left lit- tle to no legacy in the Italian theatre, and we cannot properly speak of neo-futurism or of an active Futurist avant-garde. Nonetheless, taking a closer look at some of most significant figures in Italian experimental theatre (for example, Ivrea Manifesto’s project, Carmelo Bene, Socìetas Raffaello Sanzio) this paper aims to underline the many elements that trace back to Futurist’s theatre, suggesting the need to re-read futurist artistic experiences – at least in the field of performing arts – as con- structive practices aimed at the building of a new kind of theatre. In this paper I shall try to understand whether and to which extent the shades of Futurism in and on theatre have been present on the Italian scene. Common opinion still has it that Futurism has left little legacy in the practices of contemporary Italian theatre. Differently from the visual arts, architecture and literature, futurist influences have often been local. According to Silvio D’Amico’s and Renato Simoni’s old and, in my opinion, no more valid belief, they are limited exclusively to sce- nography: «Forse, nel campo del teatro, le influenze futuriste più appa- riscenti si sono avute in materia di scenografia […]. Da ricordare a questo proposito il nome del pittore Enrico Prampolini» (Probably, in the field of theatre, the most evident futurist influences concern sceno- graphy […]. -

Asian Theatre As Method the Toki Experimental Project and Sino-Japanese Transnationalism in Performance Rossella Ferrari

Asian Theatre as Method The Toki Experimental Project and Sino-Japanese Transnationalism in Performance Rossella Ferrari The Sino-Japanese collaboration Zhuhuan shiyan jihua: yishu baocun he fazhan (Toki Experimental Project: Preservation and Development of the Traditional Performing Arts),1 is an intercultural and intergeneric performance network that brings together practitioners of kunqu, or kunju (Kun opera) — the oldest extant form of indigenous Chinese theatre (xiqu) — Japanese noh, and contemporary dance and theatre from Japan and the Sinophone region. Formally inau- gurated in 2012, Toki is a joint initiative of Sato\ Makoto, a pioneer of Japanese underground (angura) theatre and artistic director of Tokyo’s Za-Koenji Public Theatre, and Danny Yung Ning-tsun, an avantgarde theatre pioneer and coartistic director of Hong Kong’s leading trans- medial arts collective, Zuni Icosahedron, in partnership with the Jiangsu sheng yanyi jituan kunju yuan ( Jiangsu Performing Arts Group Kun Opera Theatre), based in Nanjing, China. 1. These are, respectively, the official Chinese and English denominations of the project, as chosen by the organizers. The same applies to all bilingual Chinese-English performance titles provided in the remainder of this essay. TDR: The Drama Review 61:3 (T235) Fall 2017. ©2017 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 141 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/DRAM_a_00678 by guest on 26 September 2021 Originating from a commissioned showpiece for the Japan Pavilion at World Expo 2010 in Shanghai, Zhuhuan de gushi (The Tale of the Crested Ibis), the tri-city collaboration between Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Nanjing subsequently evolved into a regular series of workshops, sem- inars, and performance coproductions devoted to the regeneration and transmission of kunqu and noh — both proclaimed Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2001 by UNESCO — through the medium of contemporary performance. -

Echoes of the Avant-Garde in American Minimalist Opera

ECHOES OF THE AVANT-GARDE IN AMERICAN MINIMALIST OPERA Ryan Scott Ebright A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Mark Katz Tim Carter Brigid Cohen Annegret Fauser Philip Rupprecht © 2014 Ryan Scott Ebright ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Ryan Scott Ebright: Echoes of the Avant-garde in American Minimalist Opera (Under the direction of Mark Katz) The closing decades of the twentieth century witnessed a resurgence of American opera, led in large part by the popular and critical success of minimalism. Based on repetitive musical structures, minimalism emerged out of the fervid artistic intermingling of mid twentieth- century American avant-garde communities, where music, film, dance, theater, technology, and the visual arts converged. Within opera, minimalism has been transformational, bringing a new, accessible musical language and an avant-garde aesthetic of experimentation and politicization. Thus, minimalism’s influence invites a reappraisal of how opera has been and continues to be defined and experienced at the turn of the twenty-first century. “Echoes of the Avant-garde in American Minimalist Opera” offers a critical history of this subgenre through case studies of Philip Glass’s Satyagraha (1980), Steve Reich’s The Cave (1993), and John Adams’s Doctor Atomic (2005). This project employs oral history and archival research as well as musical, dramatic, and dramaturgical analyses to investigate three interconnected lines of inquiry. The first traces the roots of these operas to the aesthetics and practices of the American avant-garde communities with which these composers collaborated early in their careers. -

David Greenspan

DAVID GREENSPAN PLAYS (PLAYWRIGHT AND ACTOR*) THE THINGS THAT WERE THERE * THE BUSHWICK STARR – DIRECTED BY LEE SUNDAY EVENS – 2018 THE BRIDGE OF SAN LUIS REY * TWO RIVERS THEATER – DIRECTED BY KEN RUS SCHMOLL – 2018 I'M LOOKING FOR HELEN TWELVETREES * ABRONS ARTS CENTER – DIRECTED BY LEIGH SILVERMAN – 2015 GO BACK TO WHERE YOU ARE * PLAYWRIGHTS HORIZONS – DIRECTED BY LEIGH SILVERMAN – 2011 CORALINE * – STEPHIN MERRITT/DAVID GREENSPAN MANHATTAN CLASS COMPANY – DIRECTED BY LEIGH SILVERMAN – 2009 OLD COMEDY TARGET MARGIN THEATER – DIRECTED BY DAVID HERSKOVTIS– 2008 SHE STOOPS TO COMEDY * PLAYWRIGHTS HORIZONS – DIRECTED BY DAVID GREENSPAN – 2003 DEAD MOTHER * NYSF/PUBLIC THEATER – DIRECTED BY DAVID GREENSPAN 1990 2 SAMUEL 11, ETC. HOME – DIRECTED BY DAVID GREENSPAN 1989 SOLO PERFORMANCE (*INDICATES ALSO PLAYWRIGHT) STRANGE INTERLUDE – EUGENE O’NEILL TRANSPORT GROUP – DIRECTED BY – JACK CUMMINGS III – 2017 COMPOSITION...MASTERPIECES...IDENTITY – GERTRUDE STEIN TARGET MARGIN THEATER – SELF-DIRECTED – 2015 THE PATSY – BARRY CONNERS TRANSPORT GROUP – DIRECTED BY JACK CUMMINGS III – 2011 THE MYOPIA* THE FOUNDRY THEATRE – DIRECTED BY BRIAN MERTES – 2010 PLAYS – GERTRUDE STEIN THE FOUNDRY THEATRE – SELF-DIRECTED – 2010 THE ARGUMENT* TARGET MARGIN THEATER – SELF-DIRECTED – 2007 PUBLICATIONS THE MYOPIA AND OTHER PLAYS BY DAVID GREENSPAN UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS – 2012 FOUR PLAYS AND A MONOLOGUE BY DAVID GREENSPAN NOPASSPORT PRESS – 2011 GO BACK TO WHERE YOU ARE SAMUEL FRENCH – 2013 SHE STOOPS TO COMEDY SAMUEL FRENCH – 2013 SELECTED ACTING CREDITS -

Our City Dreams

OUR CITY DREAMS A Documentary Film by Chiara Clemente 85 Minutes, Color, 2008 Digibeta, Stereo FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building, 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] Synopsis Filmed over the course of two years, OUR CITY DREAMS is an invitation to visit the creative spaces of five women artists, each of whom possesses her own energy, drive and passion. These women, who span different decades and represent diverse cultures, have one thing in common beyond making art: the city to which they have journeyed and now call home - New York. The artists profiled are Nancy Spero, who was at the forefront of the feminist movement of the late 50s and 60s and whose work continues to question the polemics of sexual identity and warfare; Marina Abramovic, a pioneer of performance art who uses her own body as a canvas to respond deeply to contemporary cultural issues; Kiki Smith, who addresses philosophical, social and spiritual aspects of the human body through work that incorporates glass, plaster, ceramic, bronze and paper; Ghada Amer, who paints erotic canvases in traditional needle and thread and who refuses to bow to the puritanical elements of Western and Islamic culture and "institutionalized feminism"; and Swoon, one of New York's most promising emerging artists, whose arresting and fugitive street art transmits the pulse of urban life. sDirector Chiara Clemente combines an intimate style of documentary filmmaking with the ephemera of city life surrounding each woman and the work she creates.