George Reynolds's Story of the Book of Mormon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINERVA TEICHERT's JESUS at the HOME of MARY and MARTHA: REIMAGINING an ORDINARY HEROINE by Tina M. Delis a Thesis Project

MINERVA TEICHERT’S JESUS AT THE HOME OF MARY AND MARTHA: REIMAGINING AN ORDINARY HEROINE by Tina M. Delis A Thesis Project Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Art History Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Minerva Teichert’s Jesus at the Home of Mary and Martha: Reimagining an Ordinary Heroine A Thesis Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at George Mason University by Tina M. Delis Bachelor of Arts George Mason University, 1987 Director: Ellen Wiley Todd, Professor Department of Art History Spring Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION For Jim, who teaches me every day that anything is possible if you have the courage to take the first step. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the many friends, relatives, and supporters who have made this happen. To begin with, Dr. Ellen Wiley Todd and Dr. Angela Ho who with great patience, spent many hours reading and editing several drafts to ensure I composed something I would personally be proud of. In addition, the faculty in the Art History program whose courses contributed to small building blocks for the overall project. Dr. Marian Wardle for sharing insights about her grandmother. Lastly, to my family who supported me in more ways than I could ever list. -

“The Pioneer's Heart: BYU-Pathway at Year

BYU-Pathway Worldwide Devotional September 24, 2019 “The Pioneer’s Heart: BYU-Pathway at Year 10” Clark G. Gilbert President of BYU-Pathway Worldwide Introduction I’m standing near the mouth of Emigration Canyon, where the first pioneers entered the Salt Lake Valley. “Those early pioneers brought a spirit of [humility and] frugality, a faith and optimism for the unknown, a longing for prophetic direction, and a spirit of personal sacrifice to their trek west.”i Today I would like to talk about how the Pioneer’s Heart shaped the development of BYU-Pathway and how it Can shape you on your own eduCational journey. The Creation of BYU-Pathway This year marks the 10th anniversary of the creation of BYU-Pathway Worldwide. LaunChed in 2009 as a simple pilot in three loCations with just 50 students, BYU-Pathway now touChes the entire ChurCh with over 45,000 students in more than 100 Countries. It was not by aCCident that BYU-Pathway would grow out of BYU-Idaho, an institution with its own pioneering heritage.ii The earliest concepts for Pathway were foCused on building a bridge to College through life skills Courses and job-foCused CertifiCates. Elder Kim B. Clark, then president of BYU-Idaho, sought counsel on those early impressions from the ChurCh Board of EduCation. Approval was granted to run limited pilots in Mesa, Arizona; Nampa, Idaho; and New York City. The Board’s decision to limit the early pilot sites proved providential because our early assumptions were a little bit right and a little bit wrong, and we needed time (and the humility) to learn and adapt. -

Conference Reports of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

)S?f n~&i~ —-. c Tttfr SIXTY=EIGHTH nnual Conference THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS, leld in the Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, April 6th, 7th, 8th and 10th, 1898, with a Full Report of the Discourses. ;o an Account of the General Conference of the Deseret Sunday School Union. COPYRIGHTED 1898. ALL BIGHTS RESERVED. Df.seret News Publishing < ompany. 1898. GENERAL CONFERENCE THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS. FIRST DAY. The Sixty-eighth annual Conference PRESIDENT WILFORD WOOD- of the Church of Jesus Christ of Lat- RUFF. ter-day Saints convened in the Taber- OPENING REMARKS. nacle, Salt Lake City, at 10 a. m. on I feel very thankful to have the Wednesday, April 6th, 1898, President privilege of meeting with so Wilford Woodruff presiding. many of the Latter-day Saints in this, our Of the general authorities present on Sixty-eighth Annual Conference of the the stand there were of the First Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Presidency—Wilford Woodruff, George Saints. I had my fears that I would Q. Cannon and Joseph P. Smith; of not be able to attend this Conference the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles— at all, as I have been quite unwell the Lorenzo Snow, Franklin D. Richards, last month; but the last day or two Brigham Young, Francis M. Lyman, I have been blessed with better health. John Henry Smith, George Teasdale, It is a great satisfaction to me to have Heber J. Grant, John W. Taylor, Mar- this privilege. I am satisfied myself riner W. -

Fall 2019 Learning Evaluation the Theme of This Portfolio Is to Exemplify Precision, Alignment, and Organization

Portfolio of Work Matthew Stoddard Fall 2019 Learning Evaluation The theme of this portfolio is to exemplify precision, alignment, and organization. I felt like that was my biggest hurdle in print publication. The process of making content look and feel organ ized is no simple matter. It requires patience, persistence, and a willingness to learn and stretch your creativity. My understanding of those ideas has grown during this course. For instance, I learned how to better align content using grid lines in the InDesign program. I discovered how to line up col umns of text using a baseline grid, or even adjusting them in small increments of leading. I even learned how to create my own grid and gutters with proper margins. From that, I saw how to properly organize pictures with their associated captions or text. I especially learned the importance of organization and preci sion when it comes to cleaning up and copy fitting text. I saw how things like optical alignment, justifying text, and avoiding eyesores, like widows or orphans, makes a world of difference. I also saw how removing unnecessary white space or using proper characters produces a more polished piece. My skills of InDesign have definitely improved in those areas. Since I had to do it many times, cleaning up or copy fitting text has almost become second nature to me. In this portfolio, I think my magazine feature turned out the best. The reason is because it was the culmination of everything I’d learned in print publishing. Using correct margins, having good line lengths, choosing a good serif/sanserif typeface, utilizing proper hierarchy, accurately implementing the paragraph and character styles, taking advantage of layers, color correcting the images, etc. -

15 BYTES :: February 2008 :: Page 5

PAGE 1 PAGE 6 PAGE 2 PAGE 7 PAGE 3 PAGE 8 PAGE 4 PAGE 9 PAGE 5 PAGE 10 February 2008 Page 5 Recently Read Minerva Teichert: Pageants in Paint by Tom Alder One of the most remarkable monographs to have been written in recent years is Marian Wardle's Minerva Teichert: Pageants in Paint. That Wardle is the granddaughter of the venerable western and Mormon muralist is inconspicuous, and with exacting detail, Wardle has created the most important work to date about Minerva Teichert. Published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name at Brigham Young University's Museum of Art, Wardle's masterful work is a precisioned arrangement of not only a credible biography and evocative coffee table book of 47 color plates, but also a comprehensive chronology (including an extensive catalogue raisonne), and Teichert's never-before published autobiography. It might be expected that a monumental treatment of Teichert's story by a family member, and published by Brigham Young University, would be a pallid re-telling of the spiritual side of Teichert, akin to a 1940s Relief Society manual; but Wardle freely narrates the salty side of Teichert as well as detailing some noteworthy disappointments in her life. However, Wardle resists writing an extensive account of many of the stories that have been re-told for decades. Yes, in her youth, Teichert slept with a gun under her pillow. Yes, she worked as a trick roper while studying in New York. 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 Yes, she often used her children's dates and any others who happened by the modest Cokeville, Organization Spotlight: Provo Wyoming home as models for some of her massive A Future for the Provo Gallery Stroll? and forceful murals. -

Wise Or Foolish: Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 57 Issue 2 Article 4 2018 Wise or Foolish: Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art Jennifer Champoux Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Champoux, Jennifer (2018) "Wise or Foolish: Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 57 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol57/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Champoux: Wise or Foolish Wise or Foolish Women in Mormon Biblical Narrative Art Jennifer Champoux isual imagery is an inescapable element of religion. Even those Vgroups that generally avoid figural imagery, such as those in Juda- ism and Islam, have visual objects with religious significance.1 In fact, as David Morgan, professor of religious studies and art history at Duke University, has argued, it is often the religions that avoid figurative imag- ery that end up with the richest material culture.2 To some extent, this is true for Mormonism. Although Mormons believe art can beautify a space, visual art is not tied to actual ritual practice. Chapels, for exam- ple, where the sacrament ordinance is performed, are built with plain walls and simple lines and typically have no paintings or sculptures. Yet, outside chapels, Mormons enjoy a vast culture of art, which includes traditional visual arts, texts, music, finely constructed temples, clothing, historical sites, and even personal devotional objects. -

Early Utah Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents

Early Utah Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Table of Contents Page Contents 2 Image List 3 Edge of the Desert , Louise Richards Farnsworth 4 Lesson Plan for Edge of the Desert Written by Ann Parker 8 Untitled, Mabel Pearl Fraser 9 Lesson Plan for Untitled Written by Betsy Quintana 10 Étude, Harriet Richards Harwood 11 Lesson Plan for Etude Written by Betsy Quintana 13 Battle of the Bulls , Minerva Kohlhepp Teichert 14 Lesson Plan for Battle of the Bulls Written by Marsha Kinghorn 17 Landscape with Blue Mountain and Stream, Florence Ellen Ware 18 Lesson Plan for Landscape with Blue Mountain Written by Bernadette Brown 19 Portrait of the Artist or Her Sister Augusta , Myra L. Sawyer 20 Lesson Plan for Portrait of the Artist or Her Augusta Written by Ila Devereaux Evening for Educators is funded in part by the StateWide Art Partnership 1 Early Utah Women Artists Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators October 28, 1998 Image List 1. Louise Richard Farnsworth (1878-1969) American Edge of the Desert Oil painting Mr. & Mrs. Joseph J. Palmer 1991.069.023 2. Mabel Pearl Frazer (1887-1981) American Untitled Oil painting Mr. & Mrs. Joseph J. Palmer 1991.069.028 3. Harriet Richards Harwood (1870-1922) American Étude , 1892 Oil painting University of Utah Collection X.035 4. Minerva Kohlhepp Teichert (1888-1976) American Battle of the Bulls Oil painting Gift of Jack and Mary Lois Wheatley 2004.2.1 5. -

Mormon Abstract

Abstract http://www.mormonartistsgroup.com/Mormon_Artists_Group/Abstract.html Welcome What's New Works Glimpses Events Freebies About MAG Contact Mormon Abstract by Stephanie K. Northrup January 2010 [i] When you think of Mormons “pushing the envelope,” what comes to mind? Deacons at the door collecting fast offerings? Try Bethanne Andersen’s The Last Supper (Place Setting). Many beautiful renditions of the Last Supper already exist, telling the story through dramatic lighting, facial expressions, and body language. Andersen tries a new perspective. She paints the dishes from which Christ eats His last mortal meal. That’s it. No people. Just us – invited to put ourselves in His shoes. The dishes are painted in soft pastel, as if on the verge of fading. This is a fleeting moment, like mortality, as He sits with His friends before making the ultimate sacrifice. By pushing the envelope, by throwing a new image at us that makes us consider the story in a new way, Andersen invites viewer participation. What a great approach to “likening the scriptures.” While Greg Olsen, Del Parson, and Simon Dewey are household names, ask most Mormons to name an abstract artist in the Church and you’ll probably get blank stares. Do Mormons make abstract art? We do. And we have been for a long time. In 1890, the church sent John Hafen and other “art missionaries” to Paris. Their assignment was to improve their skill so that they could create art for the Salt Lake Temple. What did these artists return with? Impressionism! Bright, thick brush strokes replaced traditional refined detail. -

The Coming of the Manifesto

D01OOUE A JOURNAL OF MORMON "mOUGHT THE COMING OF THE MANIFESTO Kenneth W. Godfrey An investigation of the factors which brought about the Manifesto which in turn officially terminated the practice of, if not the belief in, plural mar- riage helps to illuminate at least one process by which revelation comes. Polit- ical and social pressure was brought to bear upon Church leaders, financial sanctions seemed on the verge of destroying the Kingdom of God, and men sustained as prophets, seers and revelators reasoned, sometimes even argued, and sought the Lord in prayer for an answer to their difficulties. That God responded by confirming the rightness of what they had already concluded becomes apparent from the writings of Apostle Abraham H. Cannon, whose diaries bring additional insight to bear upon some very difficult problems. These diaries prompt and perhaps justify another article that has to do with the most publicized of all Mormon practices, plural marriage. Kenneth W. Godfrey is Director of L.D.S. Institutes and Seminaries for Arizona and New Mexico. He lives in Tempe, Arizona, with his wife and family, and holds the Ph.D. in History from Brigham Young University. Our story probably begins as early as 1831. The place is not Utah but New York, yet the setting is somewhat the same because a Mormon prophet was involved in initiating plural marriage, just as one was responsible for its cessation. Another common factor was communication with God, first from man to God and then from God to man. Though the questions were different they were at least the same in that plural marriage was the subject of both prayers. -

The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1960 The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History James N. Baumgarten Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Baumgarten, James N., "The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History" (1960). Theses and Dissertations. 4513. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 3 e F tebeebTHB ROLEROLB ardaindANDAIRD FUNCTION OF tebeebTHB SEVKMTIBS IN LJSlasLDS chweceweCHMECHURCH HISTORYWIRY A thesis presentedsenteddented to the dedepartmentA nt of history brigham youngyouyom university in partial ftlfillmeutrulfilliaent of the requirements for the degree master of arts by jalejamsjamejames N baumgartenbelbexbaxaartgart9arten august 1960 TABLE CFOF CcontentsCOBTEHTS part I1 introductionductionreductionroductionro and theology chapter bagragpag ieI1 introduction explanationN ionlon of priesthood and revrevelationlation Sutsukstatementement of problem position of the writer dedelimitationitationcitation of thesis method of procedure and sources II11 church doctrine on the seventies 8 ancient origins the revelation -

The Federal Response to Mormon Polygamy, 1854 - 1887

Mr. Peay's Horses: The Federal Response to Mormon Polygamy, 1854 - 1887 Mary K. Campbellt I. INTRODUCTION Mr. Peay was a family man. From a legal standpoint, he was also a man with a problem. The 1872 Edmunds Act had recently criminalized bigamy, polygamy, and unlawful cohabitation,1 leaving Mr. Peay in a bind. Peay had married his first wife in 1860, his second wife in 1862, and his third wife in 1867.2 He had sired numerous children by each of these women, all of whom bore his last name.3 Although Mr. Peay provided a home for each wife and her children, the Peays worked the family farm communally, often taking their meals together on the compound.4 How could Mr. Peay abide by the Act without abandoning the women and children whom he had promised to support? Hedging his bets, Mr. Peay moved in exclusively with his first wife. 5 Under the assumption that "cohabitation" required living together, he ceased to spend the night with his other families, although he continued to care for them. 6 After a jury convicted him of unlawful cohabitation in 1887,7 he argued his assumption to the Utah Supreme Court. As defense counsel asserted, "the gist of the offense is to 'ostensibly' live with [more than one woman.]' ' 8 In Mr. Peay's view, he no longer lived with his plural wives. The court emphatically rejected this interpretation of "cohabitation," declaring that "[a]ny more preposterous idea could not well be conceived."9 The use of the word "ostensibly" appeared to irritate the court. -

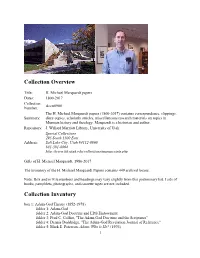

Collection Inventory Box 1: Adam-God Theory (1852-1978) Folder 1: Adam-God Folder 2: Adam-God Doctrine and LDS Endowment Folder 3: Fred C

Collection Overview Title: H. Michael Marquardt papers Dates: 1800-2017 Collection Accn0900 Number: The H. Michael Marquardt papers (1800-2017) contains correspondence, clippings, Summary: diary copies, scholarly articles, miscellaneous research materials on topics in Mormon history and theology. Marquardt is a historian and author. Repository: J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah Special Collections 295 South 1500 East Address: Salt Lake City, Utah 84112-0860 801-581-8864 http://www.lib.utah.edu/collections/manuscripts.php Gifts of H. Michael Marquardt, 1986-2017 The inventory of the H. Michael Marquardt Papers contains 449 archival boxes. Note: Box and/or File numbers and headings may vary slightly from this preliminary list. Lists of books, pamphlets, photographs, and cassette tapes are not included. Collection Inventory box 1: Adam-God Theory (1852-1978) folder 1: Adam-God folder 2: Adam-God Doctrine and LDS Endowment folder 3: Fred C. Collier, "The Adam-God Doctrine and the Scriptures" folder 4: Dennis Doddridge, "The Adam-God Revelation Journal of Reference" folder 5: Mark E. Peterson, Adam: Who is He? (1976) 1 folder 6: Adam-God Doctrine folder 7: Elwood G. Norris, Be Not Deceived, refutation of the Adam-God theory (1978) folder 8-16: Brigham Young (1852-1877) box 2: Adam-God Theory (1953-1976) folder 1: Bruce R. McConkie folder 2: George Q. Cannon on Adam-God folder 3: Fred C. Collier, "Gospel of the Father" folder 4: James R. Clark on Adam folder 5: Joseph F. Smith folder 6: Joseph Fielding Smith folder 7: Millennial Star (1853) folder 8: Fred C. Collier, "The Mormon God" folder 9: Adam-God Doctrine folder 10: Rodney Turner, "The Position of Adam in Latter-day Saint Scripture" (1953) folder 11: Chris Vlachos, "Brigham Young's False Teaching: Adam is God" (1979) folder 12: Adam-God and Plurality of Gods folder 13: Spencer W.