Heinrich Cunow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NJDARM: Collection Guide

NJDARM: Collection Guide - NEW JERSEY STATE ARCHIVES COLLECTION GUIDE Record Group: Governor Franklin Murphy (1846-1920; served 1902-1905) Series: Correspondence, 1902-1905 Accession #: 1989.009, Unknown Series #: S3400001 Guide Date: 1987 (JK) Volume: 6 c.f. [12 boxes] Box 1 | Box 2 | Box 3 | Box 4 | Box 5 | Box 6 | Box 7 | Box 8 | Box 9 | Box 10 | Box 11 | Box 12 Contents Explanatory Note: All correspondence is either to or from the Governor's office unless otherwise stated. Box 1 1. Elections, 1901-1903. 2. Primary election reform, 1902-1903. 3. Requests for interviews, 1902-1904 (2 files). 4. Taxation, 1902-1904. 5. Miscellaneous bills before State Legislature and U.S. Congress, 1902 (2 files). 6. Letters of congratulation, 1902. 7. Acknowledgements to letters recommending government appointees, 1902. 8. Fish and game, 1902-1904 (3 files). 9. Tuberculosis Sanatorium Commission, 1902-1904. 10. Invitations to various functions, April - July 1904. 11. Requests for Governor's autograph and photograph, 1902-1904. 12. Princeton Battle Monument, 1902-1904. 13. Forestry, 1901-1905. 14. Estate of Imlay Clark(e), 1902. 15. Correspondence re: railroad passes & telegraph stamps, 1902-1903. 16. Delinquent Corporations, 1901-1905 (2 files). 17. Robert H. McCarter, Attorney General, 1903-1904. 18. New Jersey Reformatories, 1902-1904 (6 files). Box 2 19. Reappointment of Minister Powell to Haiti, 1901-1902. 20. Corporations and charters, 1902-1904. 21. Miscellaneous complaint letters, December 1901-1902. file:///M|/highpoint/webdocs/state/darm/darm2011/guides/guides%20for%20pdf/s3400001.html[5/16/2011 9:33:48 AM] NJDARM: Collection Guide - 22. Joshua E. -

The Coming Crisis, the 1850S 8Th Edition

The Coming Crisis the 1850s I. American Communities A. Illinois Communities Debate Slavery 1. Lincoln-Douglas Debates II. America in 1850 A. Expansion and Growth 1. Territory 2. Population 3. South’s decline B. Politics, Culture, and National Identity 1. “American Renaissance” 2. Nathaniel Hawthorne a. The Scarlet Letter (1850) 3. Herman Melville a. Moby Dick (1851) 4. Harriet Beecher Stowe a. Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851) III. Cracks in National Unity A. The Compromise of 1850 B. Political Parties Split over Slavery 1. Mexican War’s impact a. Slavery in the territories? 2. Second American Party System a. Whigs & Democrats b. Sectional division C. Congressional Divisions 1. Underlying issues 2. States’ Rights & Slavery a. John C. Calhoun b. States’ rights: nullification c. U.S. Constitution & slavery 3. Northern Fears of “The Slave Power” a. Sectional balance: slave v. free D. Two Communities, Two Perspectives 1. Territorial expansion & slavery 2. Basic rights & liberties 3. Sectional stereotypes E. Fugitive Slave Act 1. Underground Railroad 2. Effect of Slave Narratives a. Personal liberty laws 3. Provisions 4. Anthony Burns case 5. Frederick Douglass & Harriet Jacobs 6. Effect on the North D. The Election of 1852 1. National Party system threatened 2. Winfield Scott v. Franklin Pierce E. “Young America”: The Politics of Expansion 1. Pierce’s support 2. Filibusteros a. Caribbean & Central America 3. Cuba & Ostend Manifesto IV. The Crisis of the National Party System A. The Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854) 1. Stephen A. Douglas 2. Popular sovereignty 3. Political miscalculation B. “Bleeding Kansas” 1. Proslavery: Missouri a. “Border ruffians” 2. Antislavery: New England a. -

Catalogue of United States Public Documents /July, 1902

No. 91 July, 1902 CATALOGUE OF United States Public Documents Issued Monthly BY THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS Government Printing Office Washington Government Printing Office 1902 Table of Contents Page Page General Information............................ 473 Navy Department................................. 485 Congress of United States.................... 475 Post-Oflice Department....................... 487 Laws............................................... 475 State Department...................................488 Senate............................................ 477 Treasury Department.......................... 490 House............................................. 478 War Department.................................. 494 Sheep-bound Reserve.................... 478 Smithsonian Institution..................... 496 President of United States.................... 478 Various Bureaus.................................. 496 Agriculture, Department of................ 479 Shipments to Depositories.................. 499 Interior Department..............................482 Index.................................................... i Justice, Department of......................... 485 Abbreviations Used in this Catalogue Academy............................................ acad. Mile, miles.............................................. m. Agricultural......................................agric. Miscellaneous ................................. mis. Amendments...................................amdts. Nautical............................................. -

Microfilm Publication M617, Returns from U.S

Publication Number: M-617 Publication Title: Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916 Date Published: 1968 RETURNS FROM U.S. MILITARY POSTS, 1800-1916 On the 1550 rolls of this microfilm publication, M617, are reproduced returns from U.S. military posts from the early 1800's to 1916, with a few returns extending through 1917. Most of the returns are part of Record Group 94, Records of the Adjutant General's Office; the remainder is part of Record Group 393, Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1821-1920, and Record Group 395, Records of United States Army Overseas Operations and Commands, 1898-1942. The commanding officer of every post, as well ad commanders of all other bodies of troops such as department, division, brigade, regiment, or detachment, was required by Army Regulations to submit a return (a type of personnel report) to The Adjutant General at specified intervals, usually monthly, on forms provided by that office. Several additions and modifications were made in the form over the years, but basically it was designed to show the units that were stationed at a particular post and their strength, the names and duties of the officers, the number of officers present and absent, a listing of official communications received, and a record of events. In the early 19th century the form used for the post return usually was the same as the one used for regimental or organizational returns. Printed forms were issued by the Adjutant General’s Office, but more commonly used were manuscript forms patterned after the printed forms. -

Full Text of the Ostend Manifesto

THE OSTEND MANIFESTO Aix-la-Chapelle, October 15, 1854 Sir: The undersigned, in compliance with the wish expressed by the President in the several confidential dispatches you have addressed to us, respectively, to that effect, have met in conference, first at Ostend, in Belgium, on the 9th, 10th, and 11th instants, and then at Aix-la- Chapelle, in Prussia, on the days next following, up to the date hereof. There has been a full and unreserved interchange of views and sentiments between us, which we are most happy to inform you has resulted in a cordial coincidence of opinion on the grave and important subjects submitted to our consideration. We have arrived at the conclusion, and are thoroughly convinced, that an immediate and earnest effort ought to be made by the government of the United States to purchase Cuba from Spain at any price for which it can be obtained, not exceeding the sum of $ (this item was left blank). The proposal should, in our opinion, be made in such a manner as to be presented though the necessary diplomatic forms to the Supreme Constituent Cortes about to assemble. On this momentous question, in which the people both of Spain and the United States are so deeply interested, all our proceedings ought to be open, frank, and public. They should be of such a character as to challenge the approbation of the world. We firmly believe that, in the progress of human events, the time has arrived when the vital interests of Spain are as seriously involved in the sale, as those of the United States in the purchase of the island, and that the transaction will prove equally honorable to both nations. -

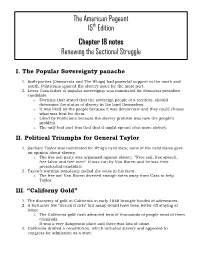

Edition Chapter 18 Notes Renewing the Sectional Struggle

The American Pageant th 15 Edition Chapter 18 notes Renewing the Sectional Struggle I. The Popular Sovereignty panache 1. Both parties (Democrats and The Whigs) had powerful support in the north and south. Politicians ignored the slavery issue for the most part. 2. Lewis Cass father of popular sovereignty was nominated for democrat president candidate. o Doctrine that stated that the sovereign people of a territory, should determine the status of slavery in the land themselves. o It was liked by the people because it was democratic and they could choose what was best for them. o Liked by Politicians because the slavery problem was now the people’s problem. o The only bad part was that that it might spread even more slavery. II. Political Triumphs for General Taylor 1. Zachary Taylor was nominated for Whig’s candidate; none of the candidates gave an opinion about slavery. o The free soil party was organized against slavery. “Free soil, free speech, free labor and free men”. It was run by Van Buren and he was their presidential candidate. 2. Taylor’s wartime popularity pulled the votes in his favor. o The free soil Van Buren diverted enough votes away from Cass to help Taylor. III. “Californy Gold” 1. The discovery of gold in California in early 1848 brought hordes of adventures. 2. A fortunate few “struck it rich” but many would have been better off staying at home. o The California gold rush attracted tens of thousands of people most of them criminals. It was a very dangerous place and there was lots of crime. -

A New Nation Struggles to Find Its Footing

The decades leading to the United States Civil War – the Antebellum era – reflect 1829, David Walker (born as a free black in North Carolina) publishes The concept of Popular Sovereignty allowed settlers into those issues of slavery, party politics, expansionism, sectionalism, economics and ‘Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World’ calling on slaves to revolt. territories to determine (by vote) if they would allow slavery within modernization. their boundaries. “Antebellum” – the phrase used in reference to the period of increasing 1831, William Lloyd Garrison publishes ‘The Liberator’ Advocated by Senator Stephen Douglas from Illinois. sectionalism which preceded the American Civil War. The abolitionist movement takes on a radical and religious element as The philosophy underpinning it dates to the English social it demands immediate emancipation. contract school of thought (mid-1600s to mid-1700s), represented Northwest Ordinance of 1787 by Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The primary affect was to creation of the Northwest Territory as the first organized territory of the United States; it established the precedent by which the Antebellum: Increasing Sectional Divisions 1845, Frederick Douglass published his autobiography United States would expand westward across North America by admitting new The publishing of his life history empowers all abolitionists to states, rather than by the expansion of existing states. 1787-1860 (A Chronology, page 1 of 2) challenge the assertions of their pro-slave counterparts, in topics The banning of slavery in the territory had the effect of establishing the Ohio ranging from the ability of slaves to learn to questions of morality River as the boundary between free and slave territory in the region between 1831, Nat Turner’s Rebellion (slave uprising) and humanity. -

3Tic. T) Aliasy Cuba, and the Slection of 1856

Qeorge <3tiC. T) aliasy Cuba, and the Slection of 1856 ISTORIANS have viewed Franklin Pierce's election to the presidency in 1852 both as a confirmation of the nation's H acceptance of the Compromise of 1850, securing sectional amity and balance, and as a mandate for the resumption of manifest destiny and expansion so vigorously pursued under James K. Polk.1 Yet within three years Pierce's policies and measures destroyed that sectional amity and all prospects of immediate expansionism, and nearly destroyed the Democratic Party which had elected him. The chief measures responsible for this turn of fortune were the Kansas- Nebraska Act and attempts to acquire Cuba. Numerous conserva- tive, "Old Fogey" Democrats entered the presidential field in 1855- 1856 to preserve the party by blocking Pierce's efforts to secure renomination. The major contenders included James Buchanan, William L. Marcy, Stephen A. Douglas and George M. Dallas of Philadelphia. Although the Kansas-Nebraska struggle destroyed the Demo- cratic Party's unity and working majority, it was Pierce's Cuban policies which revealed that collapse and prevented restoration of party harmony. Between 1853 and 1855, Pierce sought the acquisi- tion of Cuba, first, through filibuster and revolution, then through purchase, and, finally, by means of public threat. His shifting course l Among the better known works supporting this theme are: H. Barrett Learned, "William L. Marcy/' in Samuel F. Bemis, ed., American Secretaries of State and Their Diplomacy (New York, 1928), VI, 146-147; Albert K. Weinberg, Manifest Destiny (Baltimore, 1935), 182, 190, 200-201, 208-209; Henry H. -

Second Anglo-Boer War 1899 - 1902

Second Anglo-Boer War 1899 - 1902 Sources of Information National Archives UK - WO 100/68 Medal Rolls NSW infantry, Artillery, Ambulance Corps and Staff Scots All Saints College Bathurst - Honour Rolls Records of Australian Contingents to the War in South Africa 1899-1902. Lt.-Col. P L Murray 1911 History of the Bathurst Contingents 1868-1987 - Denis Chamberlain 1987 Supplement to History of the Bathurst Contingents 1868-1987 - Denis Chamberlain 1990 Website National Archives of Australia - https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ListingReports/ItemsListing.aspx for various records of Australian military enlistments etc. Website - https://www.angloboerwar.com for various rolls of non-Australian units Website - https://scotsallsaints.nsw.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/South-African-Honour-Roll.pdf Website - https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper Various contemporary NSW newspapers Abbreviations CQMS - Company Quartermaster Sergeant; DCM - Distinguished Service Medal; DSO - Distinguished Service Order; MID - Mentioned in Despatches; RQMS - Regimental Quarter-master Sergeant; RSM - Regimental Sergeant Major; RTA - Returned to Australia Indicates that further research is required Relationship to Bathurst District 1. Born Killed in Service Service Number Rank Christian Names Surname Unit(s) Service Dates 2. Educated Date of Wounding/ Illness Date of Death Place of Death War Grave Location Military Awards Local Commemoration Remarks P L MURRAY Reference Action 3. Resident 4. Enlisted 5. Next of Kin lived in area Listed Boer War Memorial, Kings 'D' Squadron, NSW Citizen's 12 April 1900 - 9 Army 414 Lance Corporal Charles Andrews Parade Original Plaque of January No NAA File found MURRAY page 83 Bushmen May 1901 1910 1 Dubbo 1877 2 All Saints College Son of Edward Spencer and 'B' Squadron, 1st NSW Mounted 19 February 1900 - Listed Scots All Saints College Army 425 Corporal Arthur Johnston Antill Marr Warren 1905, Sydney 1932 Mary Antill of Dubbo. -

1 Cuba's History and Transformation Through the Lens of the Sugar Industry Claire Priest in Recent Years, the U.S. Media Has B

Cuba’s History and Transformation through the Lens of the Sugar Industry Claire Priest In recent years, the U.S. media has been reporting widely on expanding Cuban tourism and on new entrepreneurialism in Havana and other tourist centers. Cuba’s tourism-related changes, however, are only one part of a larger transformation stemming from the many economic reforms initiated by Cuba’s government since Raúl Castro became President in 2008. Faced with unsustainable financial conditions, the Cuban government began offering limited opportunities for self-employment in the early 1990s. But in a massive shift, after country-wide open sessions for citizens to voice their suggestions, the government introduced The Guidelines of the Economic and Social Policy of the Party and the Revolution on April 18, 2011.1 The Guidelines lay out a new Cuban economic model designed to preserve socialism, while substantially downsizing government employment, broadening the private sector, and transforming the economy. The Guidelines are the Cuban equivalent of Gorbachev’s Perestroika, and Deng Xiaoping’s “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.” An understanding of Cuba’s reform process will be essential to relations between the U.S. and Cuba in the years ahead. Indeed, in contrast to U.S.-centered interpretations, the Cuban rapprochement with the U.S. likely began as part of the Castro-driven reform agenda enacted to preserve the financial sustainability of the socialist government. This paper grows out of a research trip in June and July of 2015 which involved visiting twelve historic sugar mills (ingenios) in the Trinidad, Cienfuegos, and Sagua la Grande areas, talking to workers, residents, officials, and machinists, as well as an 1 See http://www.cuba.cu/gobierno/documentos/2011/ing/l160711i.html. -

CHAPTER 14 the Coming of the Civil

CHAPTER 14 The Coming of the Civil War ANTICIPATION/REACTION Directions: Before you begin reading this chapter, place a check mark beside any of the following seven statements with which you now agree. Use the column entitled “Anticipation.” When you have completed your study of this chapter, come back to this section and place a check mark beside any of the statements with which you then agree. Use the column entitled “Reaction.” Note any variation in the placement of check marks from anticipation to reaction and explain why you changed your mind. Anticipation Reaction _____ 1. While a literary and theatrical success, Harriet _____ 1. Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin had little impact on public opinion toward slavery. _____ 2. The Kansas-Nebraska Act provoked a strong reaction _____ 2. because it proposed a more radical solution to the problem of slavery in the territories than had the Compromise of 1850. _____ 3. The Republican party founded in 1856 was the _____ 3. political voice of northern radical abolitionists. _____ 4. The Dred Scott decision implied that slavery could _____ 4. be legal anywhere in the United States. _____ 5. The Lincoln-Douglas debates were a public airing _____ 5. of the antislavery versus proslavery positions taken by the North and South before the Civil War. _____ 6. Lincoln’s election in 1860 was a popular mandate in _____ 6. support of emancipating southern slaves. _____ 7. The primary reason the South seceded in 1861 was to _____ 7. defend slavery. LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading Chapter 14 you should be able to: 1. -

William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: the War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2017 William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: The War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860 John J. Mangipano University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Latin American History Commons, Medical Humanities Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Mangipano, John J., "William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: The War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860" (2017). Dissertations. 1375. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1375 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM WALKER AND THE SEEDS OF PROGRESSIVE IMPERIALISM: THE WAR IN NICARAGUA AND THE MESSAGE OF REGENERATION, 1855-1860 by John J. Mangipano A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School and the Department of History at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: ________________________________________________ Dr. Deanne Nuwer, Committee Chair Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Heather Stur, Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew Casey, Committee Member Assistant Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Max Grivno, Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Douglas Bristol, Jr., Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr.