Exploring Fast Food Consumption Behaviours and Social Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free and Reduced Lunch Options

FREE AND REDUCED LUNCH OPTIONS All students are entitled to the same lunch selections, whether they pay regular price or qualify for free or reduced pricing. Lunches do not include bottled beverages, snacks or desserts (cookies, ice cream, bag snacks). ELEMENTARY Your child is entitled to the daily lunch or alternate choice listed on the Springfield School District website. This lunch consists of: • Meat/Meat Alternate (meat, cheese, egg, tuna, etc.) • Bread or grain • Fruit (fresh, canned or frozen) • Vegetable (fresh, canned or frozen) • Milk (1%, fat free or flavored skim) - NO SUBSTITUTE BEVERAGE MIDDLE SCHOOL A complete lunch consists of: • One entrée – see choices below. • Vegetable (hot selection or potato or celery/carrots/broccoli with dressing) • Fruit choice (fresh, canned, or frozen) or fruit juice • Milk (1%, fat-free or flavored skim)- NO SUBSTITUTE BEVERAGE Entrée choices are: • A hot sandwich – hamburger, cheeseburger, cheesesteak, chicken patty, or special sandwich of the day. • A slice of pizza • A deli sandwich, hoagie or wrap • A premium salad with a roll • The hot meal feature of the day French Fries are NOT included with the lunch unless it is specified on the menu. They are a la carte otherwise. HIGH SCHOOL Although they do not participate in the National School Lunch Program at the high school, we offer eligible students a choice of one of the following options from the different stations. These complete lunches include 16.9 oz. bottled water or 8 oz. milk, plus a piece of fresh fruit. • Deli – Sandwich or wrap, served with fresh vegetable. • Hot Entrée - served with two sides. -

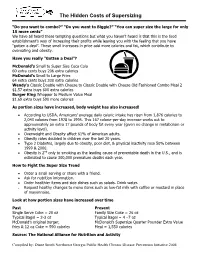

The Hidden Costs of Supersizing

The Hidden Costs of Supersizing “Do you want to combo?” “Do you want to Biggie?” “You can super size the large for only 15 more cents” We have all heard these tempting questions but what you haven’t heard is that this is the food establishment’s way of increasing their profits while leaving you with the feeling that you have “gotten a deal”. These small increases in price add more calories and fat, which contribute to overeating and obesity. Have you really ”Gotten a Deal”? McDonald’s Small to Super Size Coca Cola 60 extra cents buys 206 extra calories McDonald’s Small to Large Fries 64 extra cents buys 330 extra calories Wendy’s Classic Double with Cheese to Classic Double with Cheese Old Fashioned Combo Meal 2 $1.57 extra buys 600 extra calories Burger King Whopper to Medium Value Meal $1.69 extra buys 590 more calories As portion sizes have increased, body weight has also increased! • According to USDA, Americans’ average daily caloric intake has risen from 1,876 calories to 2,043 calories from 1978 to 1995. This 167 calorie-per-day increase works out to approximately an extra 17 pounds of body fat every year (given no change in metabolism or activity level). • Overweight and Obesity affect 61% of American adults. • Obesity rates doubled in children over the last 20 years. • Type 2 Diabetes, largely due to obesity, poor diet, & physical inactivity rose 50% between 1999 & 2000. • Obesity is 2nd only to smoking as the leading cause of preventable death in the U.S., and is estimated to cause 300,000 premature deaths each year. -

Super Size Me and the Conundrum of Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Class for the Contemporary Law-Genre Documentary Filmmaker

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 40 Number 2 Symposium—Access to Justice: Law Article 7 and Popular Culture 1-1-2007 Super Size Me and the Conundrum of Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Class for the Contemporary Law-Genre Documentary Filmmaker Regina Austin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Regina Austin, Super Size Me and the Conundrum of Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Class for the Contemporary Law-Genre Documentary Filmmaker, 40 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 687 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol40/iss2/7 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUPER SIZE ME AND THE CONUNDRUM OF RACE/ETHNICITY, GENDER, AND CLASS FOR THE CONTEMPORARY LAW-GENRE DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKER Regina Austin * I. THE INGREDIENTS OF A SUPERSIZED SUCCESS More than other genres of popular culture, documentaries are favorably disposed to what passes as a liberal perspective on social issues, including civil litigation. Newspaper headlines proclaim it, conservatives lament it, and documentarians do not dispute it. Indeed, the premise for Super Size Me,' one of the most popular documentaries of the first half decade of the 21st century, actually originated with the fast-food obesity case Pelman v. McDonald's Corp.2 According to Daily Variety, the idea for the documentary * William A. -

Lenten Fish Fry Dine-In Or Carry Out

Every Friday in Lent Saint Ambrose Including Good Friday 4:30-7:00 PM in Hilkert Hall Lenten Fish Fry Dine-In or Carry Out The Fish, Shrimp, Ravioli, and Father Rob Dinners Include 2 Side Dishes plus One Roll and Butter per Dinner Indicate number of Side Dishes based on number of dinners purchased. Choose ONE SIDE per GROUP per DINNER. Choose 1st side dish: (One per Dinner) French Fries QTY: _____ OR 2 Pierogi QTY: _____ OR Cabbage & Noodles QTY: _____ Choose 2nd side dish: (One per Dinner) Cole Slaw QTY: _____ OR Vegetable QTY: _____ OR Applesauce QTY: _____ Quantity Cost Total 1. Baked Fish 2-Piece Dinner (01)_________ x $10.00 $__________ 2. Fried Fish 2-Piece Dinner (02)_________ x $10.00 $__________ 3. Fried Shrimp 5-Piece Dinner (03)_________ x $10.00 $__________ 4. Cheese Ravioli in a Marinara Sauce Dinner (04)_________ x $10.00 $__________ 5. Father Rob Special (See Board for Dinner of the Week) (05)_________ x $10.00 $__________ The Pierogi, Cabbage & Noodle, and Mac & Cheese Dinners Include One Side Dish plus one Roll and Butter per Dinner Indicate number of Side Dishes based on number of dinners purchased. Choose ONE SIDE per DINNER. Applesauce QTY: ______ Cole Slaw QTY: ______ Quantity Cost Total 6. Pierogi Potato and Cheese 7-Piece Dinner. Choice of Regular or Deep-Fried. (06)_________ x $ 9.00 $__________ 7. Cabbage and Noodle Dinner (07)_________ x $ 6.25 $__________ 8. Macaroni & Cheese Dinner (08)_________ x $ 5.75 $__________ 9. Gluten Free Dinner (Includes Fish, Vegetable, Applesauce, and gluten-free bread.) (09)_________ x $10.00 $__________ The Value Meal Includes 2 Side Dishes plus One Roll and Butter per Dinner Indicate number of Side Dishes based on number of dinners purchased. -

Tell Me What You Eat, and I Will Tell Whom to Sue: Big Trouble Ahead for “Big Food"?

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications 2005 Tell Me What You Eat, and I Will Tell Whom to Sue: Big Trouble Ahead for “Big Food"? Richard C. Ausness University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Torts Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Richard C. Ausness, Tell Me What You Eat, and I Will Tell Whom to Sue: Big Trouble Ahead for “Big Food"?, 39 Ga. L. Rev. 839 (2005). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tell Me What You Eat, and I Will Tell Whom to Sue: Big Trouble Ahead for “Big Food"? Notes/Citation Information Georgia Law Review, Vol. 39, No. 3 (2005), pp. 839-893 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/83 TELL ME WHAT YOU EAT, AND I WILL TELL YOU WHOM TO SUE: BIG PROBLEMS AHEAD FOR "BIG FOOD"? Richard C. Ausness* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................. 841 II. PELMAN v. McDONALD'S CORP. ................... 844 III. LIABILITY THEORIES ............................. 850 A. THE DEFECT REQUIREMENT ...................... 851 B. DEFECTIVE DESIGN ............................ 852 1. The Consumer Expectation Test ....... 852 2. The Risk-Utility Test . ....................... 855 C. PRODUCT CATEGORY LIABILITY ............. -

Family Meal Deal Two Course Value Meal

FAMILY TWO COURSE MEAL DEAL £26 VALUE MEAL Any 2 adults meals + up to any 2 kids meals + up to 4 hot/cold drinks (excluding alcoholic drinks) Add any soup or dessert for only £2.50 BREAKFAST 02.00AM TILL 10.00AM LUNCH & DINNER 10.30AM TILL 02.00AM LUNCHLUNCH & & DINNER DINNER 10.30AMAM TILL TILL 02.00AM 02.00AM THE TASTE GRILL Chef’s Favourite BREAKFAST BAP ROAST CHICKEN £7.95 Free range fried or scrambled egg, pork sausage, back bacon, fried bread, £4.90 Free range fried egg, pork sausage, back bacon in a floured bap. £8.90 Half chicken with sage & onion stuffing served with vegetables & potatoes potato hash brown and baked beans. Add two slices of toast & spread: £1.95 (Only served on the 11:30 departure). or peas & chips. THE VEGGIE GRILL £7.40 Free range fried or scrambled egg, Quorn sausage, STENA LINE FISH & CHIPS Chef’s Favourite £8.90 BANGERS AND MASH fried bread, potato hash brown, tomato and baked beans. £8.90 Atlantic cod fillet, freshly battered onboard, served with chips, mushy peas Pork and leek sausages, served with traditional mashed potato and sweet onion gravy. and tartare sauce. Add two slices of bread with spread: £1.95. WINTER PORRIDGE £4.90 Porridge oats with maple syrup. GLUTEN & DAIRY FREE SOUP OF THE DAY £4.25 Freshly prepared by our onboard chefs, served with a warm crusty roll. AROMATIC VEGETARIAN KERALA CURRY BREAKFAST BAP £7.90 With cauliflower, served with basmati rice. £4.90 Free range fried egg, pork sausage, back bacon in a floured bap. -

Family Meals -The Real Value Meal

Family Meals -The Real Value Meal Let’s do dinner. Have regular “Family Meal Days”—A Day to Eat Dinner with Your Children. Eating dinner with your kids is a simple and effective way to stay involved in your children’s lives. Families that eat together regularly stay closer and more connected. Why are family meals important? More frequent family meals are associated with less substance use, fewer depressive symptoms, later initiation of sexual activity, less suicide involvement and better grades. Meals are a great time to play “follow the leader” - set a smart example. Eating with parents is also an important factor for the nutrition and eating habits of adolescents. Research shows that family meals are associated with higher intakes of fruits, vegetables and dairy products. Adolescents who report frequent family meals are also more likely to have a healthy weight and less likely to develop disordered eating habits. With today’s busy lifestyles it can be a challenge to eat meals together. These tried and true strategies can make it easier. Make family mealtime a priority. Schedule family meals for the week and write them on the calendar. If you know you can’t have a family dinner, make a date for a family breakfast. Keep it simple. Tuna sandwiches with sliced fruit can be made in minutes. Pasta and bottled spaghetti sauce with salad and bread make a great 30 minute meal. Get kids involved. Have them help with washing fruits and vegetables, setting the table or stirring ingredients. As they get older, ask them to be responsible for making one meal a month. -

Nutrition Standards and Implementation Guide

nutrition standards and implementation guide get healthy philly · philadelphia department of public health www.foodfitphilly.org www.phila.gov/nutritionstandards Get Healthy Philly is a project of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health and is made possible, in part, by funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PHILADELPHIA COMPREHENSIVE FOOD STANDARDS WHY FOOD STANDARDS? By implementing these standards the City of Among the ten largest cities, Philadelphia has some of Philadelphia will: the highest rates of poverty and related chronic diseases, • improve the health of Philadelphians, including nutritionally including hypertension, type 2 diabetes and heart disease. vulnerable populations such as youth and seniors; At the same time, research clearly indicates that improving dietary intake and ensuring ongoing access to nourishing • reduce the economic burden of health care costs foods can lower chronic disease risk. For example, research associated with heart disease, stroke and heart and has shown that lowering excessive sodium intake from kidney failure; and the average 3400 mg/day to the recommended 2300 mg/ • serve as a model for other large institutions, employers day can lower high blood pressure, and the risk for heart and programs. disease and stroke. The nutrition standards are based on: The more than 20 million meals • the 2015 Dietary Guidelines, served every year by City agencies • food standards adopted by other local and federal and city-funded programs are an governments and opportunity to help Philadelphians • review and feedback from City Agencies.1 improve their diets and their health. As dietary guidelines and public health information is While many agencies have existing nutrition recommenda- updated, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health tions, they can be inconsistent across programs, or not (PDPH) will make periodic revisions to the standards to reflective of the latest dietary guidance. -

CAFETERIAS/CAFES Implementation Guide

Food Standards CAFETERIAS/CAFES Implementation Guide Department of Health Overview The standards for Cafeterias/Cafes include 20 guidelines that can help increase the availability This guide of healthier food and beverage provides examples, options. By following the standards, tips, and tools to help your cafeteria can make the you apply each standard healthy choice the easy choice to your cafeteria. Share this for employees and visitors. with vendors, caterers, and staff involved in planning, purchasing, or preparing food and beverages served. Table of Contents Fruits and Vegetables..................................................................................................................................3 Sandwiches, Salads, and Entrees..............................................................................................................3 Tips to Reduce Sodium.....................................................................................................................3 Soups and Sides...........................................................................................................................................4 Breakfast Breads, Desserts, and Snacks.................................................................................................4 Tips to Reduce Calories in Breakfast Breads and Desserts.......................................................4 How to Calculate Calories and Sodium in Food............................................................................5 Tips to Implement Standards -

Alternative Approaches to Resource Conflicts

Vanclay, J.K., 2005. Gunns, Greens and Silk: alternative approaches to resource conflicts. Paper to “Burning Issues in Forestry ”, 22 nd biennial conference of the Institute of Foresters of Australia, 10-14 April 2005, Mount Gambier S.A. Gunns, Greens and Silk: alternative approaches to resource conflicts Jerome K. Vanclay Southern Cross University, PO Box 157, Lismore NSW 2480 Summary Many Australian foresters remain unaware of the McLibel case, a 15-year public relations disaster that followed a litigation attempt by the McDonald’s hamburger chain. Recent litigation by Gunns Limited against 20 environmental activists appears to ignore the lessons from that case. The McLibel litigation led to a costly lose-lose outcome, whereas reforms by McDonald’s following a critical movie created a win-win situation in which McDonald’s improved their reputation and their customers gained better food. Parallels that may contribute to such win-win outcomes in forestry are examined. Adaptive collaborative management informed by participatory modelling may be a more productive approach than litigation, and should produce a more durable outcome. Keywords: litigation, negotiation, adaptive collaborative management, McLibel, Gunns20 Introduction In his best-selling book ‘Guns, germs and steel’, Jared Diamond (1997) examined a question posed by one of his PNG colleagues: “Why is it that you white people developed so much cargo ... ?”. Diamond argued that the underlying reason for the good fortune enjoyed by some cultures was geography, because large land masses facilitated the development of societies better able share technologies and learn from their experiences. The title of this paper is a parody of Diamond’s title, because I explore “Why is it that Gunns have initiated so many lawsuits?”, referring to the litigation initiated recently by the forestry company Gunns (White 2005). -

Tips for a Popular Manageable and Profitable Menu

Resource 11: Tips for a popular, manageable, and profitable menu Food Quality Use fun shapes and patterns and give foods fun names. Offer meal deals such as the Make foods fun ‘Boost Pack’, ‘Energizer’ or ‘Fruitylicious Pack’ or name meal deals after prominent sports people. Offer tasty foods Free taste tests are a good idea for testing out new menu ideas. This can help to gauge their popularity before being added to the menu. Ensure foods are packaged and displayed well so they look appetising by using plenty of Visual appeal colourful foods (wrapping in plastic and using clear containers help). Suitability of items for all age groups Offer a variety of serve sizes such as half sandwiches and/or wraps. Ensure that different needs and tastes are accommodated. For example, provide a Sufficient variety selection of sandwich fillings, vegetarian/meat based meals, savoury/sweet selections and a variety of base sauces for dishes. Seasonal foods Fruit and vegetables in season generally tend to be cheaper. Talk to local suppliers about which items offer the best quality, freshness, taste and value. Efficiency and Economy Large numbers of menu items can also be harder to manage. Add new items for variety, but don’t forget to remove old ones. Specials are a good way to offer variety week-to-week without Balance variety and greatly increasing the number of items on the menu. choice Determine a manageable number of menu items that is appropriate for the circumstances such as preparation time and available space. Many canteens adopt a policy to mark-up less healthy RED or AMBER items in order to promote healthier GREEN foods and drinks. -

Central 301 Food Service

Central 301 Food Service Welcomes Back Students With A Whole New World Ordering Procedures ★ High School and Middle School Students/Staff will place their lunch orders daily via their school Google Lunch Order form. ○ This form will be located under the districts website, District Departments > Food Service > School Lunch Order forms ★ The results of these orders will provide: ○ Food counts for the kitchen staff by serving locations and lunch periods ○ This will also help with the setup of food at the proper locations ★ Orders placed via this form will be used to charge student’s/staff accounts via their student ID that is being collected. This ensures contactless check-outs and limited time in lines. ○ There will be no need to stand in a cashier line to check out ○ No need for hand keying ID numbers into pin pads ○ Limits touchpoints Updated Payment Procedures ★ In order to provide the safest, contactless transition for payments, Central 301 Food Service departments district-wide are going “cashless”. All payments must be updated through our online payment processing system, MySchoolBucks (Heartland Payment Systems). ★ Cashiers will not accept cash or checks at the Point of Sale cashier stations. ★ Setting up a free MySchoolBucks account is easy. Links can be found under the For Parents tab > Lunch Information on the district website. To set up an account you will need your student’s name and ID number. Funds can be added using your credit/debit card or electronic check. ○ Some features with MySchoolBucks are: ■ Easy way to add funds with auto replenish options available ■ View cafeteria purchases ■ Check your student’s account balance ■ Receive low balance alerts depending on your preferences setup MySchoolBucks Setup Serving Procedures ★ All lunch menu options will be pre-made and served in clear individual containers, styrofoam or paper bags.