From Wallet to Waistline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free and Reduced Lunch Options

FREE AND REDUCED LUNCH OPTIONS All students are entitled to the same lunch selections, whether they pay regular price or qualify for free or reduced pricing. Lunches do not include bottled beverages, snacks or desserts (cookies, ice cream, bag snacks). ELEMENTARY Your child is entitled to the daily lunch or alternate choice listed on the Springfield School District website. This lunch consists of: • Meat/Meat Alternate (meat, cheese, egg, tuna, etc.) • Bread or grain • Fruit (fresh, canned or frozen) • Vegetable (fresh, canned or frozen) • Milk (1%, fat free or flavored skim) - NO SUBSTITUTE BEVERAGE MIDDLE SCHOOL A complete lunch consists of: • One entrée – see choices below. • Vegetable (hot selection or potato or celery/carrots/broccoli with dressing) • Fruit choice (fresh, canned, or frozen) or fruit juice • Milk (1%, fat-free or flavored skim)- NO SUBSTITUTE BEVERAGE Entrée choices are: • A hot sandwich – hamburger, cheeseburger, cheesesteak, chicken patty, or special sandwich of the day. • A slice of pizza • A deli sandwich, hoagie or wrap • A premium salad with a roll • The hot meal feature of the day French Fries are NOT included with the lunch unless it is specified on the menu. They are a la carte otherwise. HIGH SCHOOL Although they do not participate in the National School Lunch Program at the high school, we offer eligible students a choice of one of the following options from the different stations. These complete lunches include 16.9 oz. bottled water or 8 oz. milk, plus a piece of fresh fruit. • Deli – Sandwich or wrap, served with fresh vegetable. • Hot Entrée - served with two sides. -

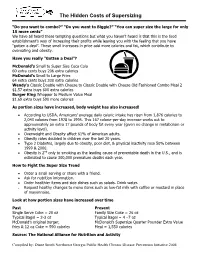

The Hidden Costs of Supersizing

The Hidden Costs of Supersizing “Do you want to combo?” “Do you want to Biggie?” “You can super size the large for only 15 more cents” We have all heard these tempting questions but what you haven’t heard is that this is the food establishment’s way of increasing their profits while leaving you with the feeling that you have “gotten a deal”. These small increases in price add more calories and fat, which contribute to overeating and obesity. Have you really ”Gotten a Deal”? McDonald’s Small to Super Size Coca Cola 60 extra cents buys 206 extra calories McDonald’s Small to Large Fries 64 extra cents buys 330 extra calories Wendy’s Classic Double with Cheese to Classic Double with Cheese Old Fashioned Combo Meal 2 $1.57 extra buys 600 extra calories Burger King Whopper to Medium Value Meal $1.69 extra buys 590 more calories As portion sizes have increased, body weight has also increased! • According to USDA, Americans’ average daily caloric intake has risen from 1,876 calories to 2,043 calories from 1978 to 1995. This 167 calorie-per-day increase works out to approximately an extra 17 pounds of body fat every year (given no change in metabolism or activity level). • Overweight and Obesity affect 61% of American adults. • Obesity rates doubled in children over the last 20 years. • Type 2 Diabetes, largely due to obesity, poor diet, & physical inactivity rose 50% between 1999 & 2000. • Obesity is 2nd only to smoking as the leading cause of preventable death in the U.S., and is estimated to cause 300,000 premature deaths each year. -

Lenten Fish Fry Dine-In Or Carry Out

Every Friday in Lent Saint Ambrose Including Good Friday 4:30-7:00 PM in Hilkert Hall Lenten Fish Fry Dine-In or Carry Out The Fish, Shrimp, Ravioli, and Father Rob Dinners Include 2 Side Dishes plus One Roll and Butter per Dinner Indicate number of Side Dishes based on number of dinners purchased. Choose ONE SIDE per GROUP per DINNER. Choose 1st side dish: (One per Dinner) French Fries QTY: _____ OR 2 Pierogi QTY: _____ OR Cabbage & Noodles QTY: _____ Choose 2nd side dish: (One per Dinner) Cole Slaw QTY: _____ OR Vegetable QTY: _____ OR Applesauce QTY: _____ Quantity Cost Total 1. Baked Fish 2-Piece Dinner (01)_________ x $10.00 $__________ 2. Fried Fish 2-Piece Dinner (02)_________ x $10.00 $__________ 3. Fried Shrimp 5-Piece Dinner (03)_________ x $10.00 $__________ 4. Cheese Ravioli in a Marinara Sauce Dinner (04)_________ x $10.00 $__________ 5. Father Rob Special (See Board for Dinner of the Week) (05)_________ x $10.00 $__________ The Pierogi, Cabbage & Noodle, and Mac & Cheese Dinners Include One Side Dish plus one Roll and Butter per Dinner Indicate number of Side Dishes based on number of dinners purchased. Choose ONE SIDE per DINNER. Applesauce QTY: ______ Cole Slaw QTY: ______ Quantity Cost Total 6. Pierogi Potato and Cheese 7-Piece Dinner. Choice of Regular or Deep-Fried. (06)_________ x $ 9.00 $__________ 7. Cabbage and Noodle Dinner (07)_________ x $ 6.25 $__________ 8. Macaroni & Cheese Dinner (08)_________ x $ 5.75 $__________ 9. Gluten Free Dinner (Includes Fish, Vegetable, Applesauce, and gluten-free bread.) (09)_________ x $10.00 $__________ The Value Meal Includes 2 Side Dishes plus One Roll and Butter per Dinner Indicate number of Side Dishes based on number of dinners purchased. -

BURGER KING® USA Nutritionals: Core, Regional and Limited Time Offerings

BURGER KING® USA Nutritionals: Core, Regional and Limited Time Offerings July 2012 Allergens ▲ serving size (g) size serving Calories Calories from fat Total fat (g) Saturated Fat (g) Trans Fat (g) Chol (mg) Sodium (mg) Total Carb (g) FiberDietary (g) Protein (g) Nutrition facts (g) Sugar Total WHOPPER® Sandwiches WHOPPER® Sandwich 290 670 360 40 11 1 75 980 51 3 11 29 WES w/o Mayo 268 510 200 23 9 0.5 65 840 51 3 11 28 WS WHOPPER® Sandwich with Cheese 315 760 430 47 16 1 100 1410 53 3 11 33 MWES w/o Mayo 294 600 270 30 14 1 85 1270 53 3 11 32 MWS DOUBLE WHOPPER® Sandwich 373 900 510 57 19 1.5 140 1050 51 3 11 47 WES w/o Mayo 352 740 350 39 16 1 130 910 51 3 11 47 WS DOUBLE WHOPPER® Sandwich with Cheese 398 990 580 65 24 1.5 160 1480 53 3 11 52 MWES w/o Mayo 376 830 420 47 21 1.5 150 1340 53 3 11 52 MWS TRIPLE WHOPPER® Sandwich 455 1140 670 75 27 2 205 1110 51 3 11 67 WES w/o Mayo 434 980 510 57 24 1.5 190 970 51 3 11 66 WS TRIPLE WHOPPER® Sandwich With Cheese 480 1230 740 82 32 2 225 1550 53 3 11 71 MWES w/o Mayo 459 1070 580 64 29 2 215 1410 53 3 11 71 MWS Texas DOUBLE WHOPPER® Sandwich 410 1040 620 69 26 2 175 1770 50 3 8 56 MWES WHOPPER JR.® Sandwich 147 340 160 18 5 0 40 520 32 1 7 14 WES w/o Mayo 136 260 90 9 4 0 35 450 32 1 7 14 WS WHOPPER JR.® Sandwich with Cheese 159 380 190 21 8 0.5 50 710 33 1 7 16 MWES w/o Mayo 137 300 110 13 6 0 45 640 32 1 7 16 MWS Allergens ▲ serving size (g) size serving Calories Calories from fat Total fat (g) Saturated Fat (g) Trans Fat (g) Chol (mg) Sodium (mg) Total Carb (g) FiberDietary (g) Protein -

Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits Launches Search

Contacts: Melissa Libby, Melissa Libby & Associates [email protected] 404-816-3068 Kim Englehardt, Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits [email protected] 404-459-4660 POPEYES® CHICKEN & BISCUITS LAUNCHES SEARCH FOR “TEAM CANADA” Significant Expansion Targeted for 2003 ATLANTA, Jan. 20, 2003 -- After a record-breaking franchising year in 2002, Popeyes® Chicken & Biscuits, a division of AFC Enterprises, Inc. (NASDAQ:AFCE), is hoping to continue the momentum with a focus on Canada. Plans to recruit “Team Canada,” an all-star group of experienced multi-unit restaurateurs, will be announced at the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC) Conference in Whistler, Canada held Jan. 19 - 21. Popeyes plans to award exclusive territory development areas to franchisees throughout the country by the end of 2003. “With Popeyes’ Acadian roots, you could say the brand is ‘coming home’ to this part of the world,” said Russ Sumrall, vice president of international development for Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits. “We will be selecting the multi-unit restaurateurs who represent the best of the best to bring our flavorful chicken and Louisiana dishes to Canada.” Olive Hospitality Inc. signed an agreement to develop 30 new restaurant locations exclusively in the greater Vancouver area. Popeyes has recently opened two restaurants in the Vancouver area. There are 15 restaurants currently open in the greater Toronto area, but that area is still available to be further developed as an exclusive development territory. Canadian multi-unit operators interested in Popeyes’ Team Canada can contact Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits for more information. This is not an offer to sell a franchise. Complete information about this opportunity is available in the Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits franchise disclosure document. -

Family Meal Deal Two Course Value Meal

FAMILY TWO COURSE MEAL DEAL £26 VALUE MEAL Any 2 adults meals + up to any 2 kids meals + up to 4 hot/cold drinks (excluding alcoholic drinks) Add any soup or dessert for only £2.50 BREAKFAST 02.00AM TILL 10.00AM LUNCH & DINNER 10.30AM TILL 02.00AM LUNCHLUNCH & & DINNER DINNER 10.30AMAM TILL TILL 02.00AM 02.00AM THE TASTE GRILL Chef’s Favourite BREAKFAST BAP ROAST CHICKEN £7.95 Free range fried or scrambled egg, pork sausage, back bacon, fried bread, £4.90 Free range fried egg, pork sausage, back bacon in a floured bap. £8.90 Half chicken with sage & onion stuffing served with vegetables & potatoes potato hash brown and baked beans. Add two slices of toast & spread: £1.95 (Only served on the 11:30 departure). or peas & chips. THE VEGGIE GRILL £7.40 Free range fried or scrambled egg, Quorn sausage, STENA LINE FISH & CHIPS Chef’s Favourite £8.90 BANGERS AND MASH fried bread, potato hash brown, tomato and baked beans. £8.90 Atlantic cod fillet, freshly battered onboard, served with chips, mushy peas Pork and leek sausages, served with traditional mashed potato and sweet onion gravy. and tartare sauce. Add two slices of bread with spread: £1.95. WINTER PORRIDGE £4.90 Porridge oats with maple syrup. GLUTEN & DAIRY FREE SOUP OF THE DAY £4.25 Freshly prepared by our onboard chefs, served with a warm crusty roll. AROMATIC VEGETARIAN KERALA CURRY BREAKFAST BAP £7.90 With cauliflower, served with basmati rice. £4.90 Free range fried egg, pork sausage, back bacon in a floured bap. -

Family Meals -The Real Value Meal

Family Meals -The Real Value Meal Let’s do dinner. Have regular “Family Meal Days”—A Day to Eat Dinner with Your Children. Eating dinner with your kids is a simple and effective way to stay involved in your children’s lives. Families that eat together regularly stay closer and more connected. Why are family meals important? More frequent family meals are associated with less substance use, fewer depressive symptoms, later initiation of sexual activity, less suicide involvement and better grades. Meals are a great time to play “follow the leader” - set a smart example. Eating with parents is also an important factor for the nutrition and eating habits of adolescents. Research shows that family meals are associated with higher intakes of fruits, vegetables and dairy products. Adolescents who report frequent family meals are also more likely to have a healthy weight and less likely to develop disordered eating habits. With today’s busy lifestyles it can be a challenge to eat meals together. These tried and true strategies can make it easier. Make family mealtime a priority. Schedule family meals for the week and write them on the calendar. If you know you can’t have a family dinner, make a date for a family breakfast. Keep it simple. Tuna sandwiches with sliced fruit can be made in minutes. Pasta and bottled spaghetti sauce with salad and bread make a great 30 minute meal. Get kids involved. Have them help with washing fruits and vegetables, setting the table or stirring ingredients. As they get older, ask them to be responsible for making one meal a month. -

Ramstein Dining Locations

RAMSTEIN DINING LOCATIONS (See Ramstein Map on Back) DINING FAST FOOD (12) Deuts~he Ka tine 480-5353 (8) Enlisted Club 480-5637 (4) Burger King 480-2555 Chili's Restaurant •• Open to all ranks! Offers all/lientic German Meals (1) Bowling Center 480-5547 Offers typical Burger King menu plus breakfast . Breakfast Mon ay-Friday, 0630-1100 Sandwiches, salads, and daily specials Orders "To Go" 480-6890 & "Call Ahead" 480-5258 Lunch Monda Friday, 1100-1600 Monday-Thursday, 0630-2100 Mexican dishes, steaks, salads, burgers Monday-Thursday, 1100-2200 Friday-Saturday, 0600-2300 Bldg 2400 (adj outhside Chapel) Friday-Saturday, 1100-2300 Sunday-Saturday, 1100-2200 Sunday, 0600-2100 JRRockers' •• Open ro all ranks until 2200 daily! Sunday-Holidays, 1200-2200 . Drive thru Friday & Saturday open 24 hours (13) Dcutsches H' us 06371-4659-3700 Bldg 2139.(east of 435th Medical Group) Breakfast, sandwiches, salads, burgers, grill items Pork, beef, all fish dishes, Bldg 1135 (east of terminal) Monday-Tuesday, 0630-1030 & 1100-2200 soups/salads, /ld pastas Wednesday-Friday, 0630-1030 & 1100-2400 (5) Doner Kebab 480-5866 Breakfast Mo day-Friday, 0700~1000 (2) Community Center Saturday, 0990-1330 & 1400-2400 Lunch MOl day-Thursday, 1130-1330 Pizza Gallerie 480-6760 Also offers Robin Hood sandwiches and pizza Sunday-Holiday, 0900-1330 & 1400-2200 Monday-Saturday, 1030-2200 Fri ay, 1130-1300 Ca/zones, pizza, salads, and sandwiches Bldg 2140 (adj Bowling Center) Sunday, 1200-2100 DlImer MOlday-Thursday, 1730-2030 Monday-Saturday, 1100-2100 Bldg 2171 (east of 435th Medical Group) Bldg 544 (east of Prime Knight) Sunday, 1600-2100, Holiday,·Closed (9) Officers' Club 480-2824 China Town Restaurant 480-2908 . -

Nutrition Standards and Implementation Guide

nutrition standards and implementation guide get healthy philly · philadelphia department of public health www.foodfitphilly.org www.phila.gov/nutritionstandards Get Healthy Philly is a project of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health and is made possible, in part, by funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PHILADELPHIA COMPREHENSIVE FOOD STANDARDS WHY FOOD STANDARDS? By implementing these standards the City of Among the ten largest cities, Philadelphia has some of Philadelphia will: the highest rates of poverty and related chronic diseases, • improve the health of Philadelphians, including nutritionally including hypertension, type 2 diabetes and heart disease. vulnerable populations such as youth and seniors; At the same time, research clearly indicates that improving dietary intake and ensuring ongoing access to nourishing • reduce the economic burden of health care costs foods can lower chronic disease risk. For example, research associated with heart disease, stroke and heart and has shown that lowering excessive sodium intake from kidney failure; and the average 3400 mg/day to the recommended 2300 mg/ • serve as a model for other large institutions, employers day can lower high blood pressure, and the risk for heart and programs. disease and stroke. The nutrition standards are based on: The more than 20 million meals • the 2015 Dietary Guidelines, served every year by City agencies • food standards adopted by other local and federal and city-funded programs are an governments and opportunity to help Philadelphians • review and feedback from City Agencies.1 improve their diets and their health. As dietary guidelines and public health information is While many agencies have existing nutrition recommenda- updated, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health tions, they can be inconsistent across programs, or not (PDPH) will make periodic revisions to the standards to reflective of the latest dietary guidance. -

BURGER KING® Brand Debuts New Holiday-Inspired Menu Items New, LimitedTimeOnly Holiday Sweets Promise to Satisfy All Taste Buds

1/21/2015 Burger King INVESTOR INFORMATION | Press Releases BURGER KING® Brand Debuts New Holiday-Inspired Menu Items New, LimitedTimeOnly Holiday Sweets Promise to Satisfy All Taste Buds MIAMI(BUSINESS WIRE)Oct. 18, 2012 To celebrate the start of the holiday season, Burger King Worldwide, Inc. (NYSE: BKW) today proudly unveiled additions to its popular dessert menu: the Gingerbread Cookie Sundae and Gingerbread Cookie Shake. Infused with classic holiday flavors that you have grown to love, each gingerbread treat is sure to get everyone into the spirit of the season while fulfilling those cookie cravings. For cinnamonflavor enthusiasts, BK® will also feature the irresistible Cinnabon® Minibon® Rolls, baked fresh daily using the world‘s best cinnamon and covered in rich, creamy frosting. Treat yourself to a sweet morning, snack onthego or pair with your favorite BK® meal. "As part of our latest menu innovations, we are delighted to offer our BURGER KING® guests delicious new items that are inspired by holiday flavors of home, from our festive gingerbread cookie desserts to our warm, Cinnabon® Minibon® Rolls," said Roberta Colleta, vice president of North America marketing, Burger King Worldwide. "During this busy holiday season, take time to reward yourself with any of our three tasty new menu items." Give your taste buds something they will love with the delicious and flavorful dessert menu innovations, designed with our guests in mind: Gingerbread Cookie Sundae ~ BK® invites guests to get into the holiday spirit with a satisfying and delicious dessert that starts with rich and creamy vanilla soft serve, topped with crispy gingersnap cookie crumbles and finished with a swirl of sweet gingerbread sauce. -

A Future of Opportunity

A Future of Opportunity AFC Enterprises, Inc. 2004 Annual Report A Future of Opportunity We made good decisions and will continue to do so, to improve our chances to win and win big, for the benefit of each and every stakeholder for years to come. A LETTER TO OUR STAKEHOLDERS Dear Stakeholders, Over the past two years, we have worked diligently to do what was necessary and prudent to unlock the greatest value at AFC. As I look back over this past year, I must say that I am pleased with what we have accomplished — especially since we set out specifically to execute many of these initiatives twelve months ago. Frank Belatti As 2004 began, we were determined to assess and improve our adminis- Chairman and CEO trative processes and procedures, resume trading on NASDAQ, evaluate and make appropriate changes to our portfolio, collapse the corporate center, and turn our undivided attention to growing the Popeyes brand. Despite facing what often were competing priorities, our people remained steadfast and resolute, never wavering from the goal of getting the job done. They worked hard to do what had to be done in the appropriate sequence, while delivering our desired results. Maintaining a proper balance throughout the year, we were careful to protect the integrity of our brands, the investments of our franchisees, and the work environment of our employees. All the while, we were seeking to improve the value of the enterprise for our shareholders. The fact that we succeeded in maintaining that balance bodes very well for the future of this company because the majority of the people who did the hard work during 2004 remain with the company and are now focused on our 2005 objectives. -

CAFETERIAS/CAFES Implementation Guide

Food Standards CAFETERIAS/CAFES Implementation Guide Department of Health Overview The standards for Cafeterias/Cafes include 20 guidelines that can help increase the availability This guide of healthier food and beverage provides examples, options. By following the standards, tips, and tools to help your cafeteria can make the you apply each standard healthy choice the easy choice to your cafeteria. Share this for employees and visitors. with vendors, caterers, and staff involved in planning, purchasing, or preparing food and beverages served. Table of Contents Fruits and Vegetables..................................................................................................................................3 Sandwiches, Salads, and Entrees..............................................................................................................3 Tips to Reduce Sodium.....................................................................................................................3 Soups and Sides...........................................................................................................................................4 Breakfast Breads, Desserts, and Snacks.................................................................................................4 Tips to Reduce Calories in Breakfast Breads and Desserts.......................................................4 How to Calculate Calories and Sodium in Food............................................................................5 Tips to Implement Standards