Emergency Assistance for Chrysler Financial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Court File No. CV-19-614593-00CL

Court File No. CV-19-614593-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (COMMERCIAL LIST) B E T W E E N: CORNER FLAG LLC Applicant – and – ERWIN HYMER GROUP NORTH AMERICA, INC. Respondent APPLICATION UNDER section 243 of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. B-3, as amended, and under section 101 of the Courts of Justice Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. C.43 MOTION RECORD OF ALVAREZ & MARSAL CANADA INC., IN ITS CAPACITY AS COURT-APPOINTED RECEIVER AND MANAGER OF ERWIN HYMER GROUP NORTH AMERICA, INC. (Motion for Approval of Sales Process) March 20, 2019 OSLER, HOSKIN & HARCOURT LLP 100 King Street West 1 First Canadian Place Suite 6200, P.O. Box 50 Toronto, ON M5X 1B8 Tracy C. Sandler (LSO# 32443N) Tel: 416.862.5890 Jeremy Dacks (LSO# 41851R) Tel: 416.862.4923 Fax: 416.862.6666 Counsel for the Receiver – 2 – TO: THE SERVICE LIST AND TO: THE SUPPLEMENTAL SERVICE LIST Court File No. CV-19-614593-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST BETWEEN: CORNER FLAG LLC Applicant – and – ERWIN HYMER GROUP NORTH AMERICA, INC. Respondents SERVICE LIST (as at March 20, 2019) PARTY CONTACT BLAKE, CASSELS & GRAYDON LLP Pamela L.J. Huff Commerce Court West Tel: 416.863.2958 199 Bay Street, Suite 4600 Email: [email protected] Toronto, ON M5L 1A9 Linc Rogers Tel: 416.863.4168 Fax: 416.863.2653 Email: [email protected] Counsel to the Applicant Aryo Shalviri Tel: 416.863.2962 Email: [email protected] Vanja Ginic Tel: 416.863.3278 Email: [email protected] Caitlin McIntyre Tel: 416.863.4174 Email: [email protected] [2] ALVAREZ & MARSAL CANADA INC. -

OSBC - Division of Consumer and Mortgage Lending Approved Notification Registrants As of 3/28/2016

OSBC - Division of Consumer and Mortgage Lending Approved Notification Registrants as of 3/28/2016 The list is sorted alphabetically by the company name. To search the list, use the Find feature ("CTRL+F") available in your PDF reader. License No. Name DBA Name Address City State Zip NOT.0006475 21st Mortgage Corporation 620 Market Street Knoxville TN 37902 NOT.0026804 4 Seasons Midwest LLC 317 Columbus Ave. Newton KS 67114 NOT.0005346 54 Auto and RV, LLC 11932 SW HIGHWAY 54 AUGUSTA KS 67010 NOT.0025567 7th Street Auto Sales, Inc 932 S 7TH ST KANSAS CITY KS 66105 NOT.0025437 A & A Motorsports, Inc. 5141 N 139th St. Kansas City KS 66109 NOT.0005528 A & M Home Furnishings 6960 W 105th St OVERLAND PARK KS 66212 NOT.0006036 A&A Appliance Inc 429 E 3RD Hutchinson KS 67501 NOT.0025945 A&M Finance, LLC A&M Finance 1110 NO ROGERS RD OLATHE KS 66062 NOT.0025925 A&W Water LLC EcoWater Systems 327 1/2 W Stolp Ave Medicine Lodge KS 67104 NOT.0005079 A-1 APHCE Inc A-1 Plumbing, Heating, Cooling, & Electrical 7440 MORRILL RD WAKARUSA KS 66546 NOT.0025916 A-1 Premium Acceptance, Inc. King of Kash 8304 Wornall Road Kansas City MO 64114 NOT.0025401 A-OK1, LLC A-OK, A-OK Cash Center, A-OK Pawn 2021 N. Amidon Wichita KS 67203 NOT.0005830 A.B. May Company 7100 E 50th St. Kansas City MO 64129 NOT.0026268 AAA Loans LLC 1212 Fleming St. Garden City KS 67846 NOT.0006242 Aberle Ford Inc 1025 MAIN STREET Sabetha KS 66534 NOT.0004554 Abilene Mercantile Company Inc RHV DO IT BEST HARDWARE 305 N Buckeye Abilene KS 67410 NOT.0005825 Abilene Rent-All & Sales Inc 1701 W First St Abilene KS 67410 NOT.0006035 Abram Ready Mix, Inc 915 E. -

2014 ICCC Notification & Fees Registered Businesses

2014 ICCC Notification & Fees Registered Businesses Business Name #1 Auto Accord Creditor Services, LLC Afni Philippines Inc. 21st Mortgage Corp. Account Control Technology, Afni, Inc. previously Anderson Inc. Financial Network, Inc. 24 Asset Management Corp Account Discovery Systems, AFS Acceptance LLC 360 Mortgage Group, LLC LLC AGCO Finance LLC 3Point Real Estate Solutions, Account Recovery Specialists, LLC Inc AGCO Finance LLC 3Point Real Estate Solutions, Account Resolution Group, LLC Agricredit Acceptance LLC LLC Account Services Collections, Agricredit Acceptance LLC 3rd Ave Auto Sales Inc. dba Account Services/ AIH Receivable Management 4 Star Resolution LLC Check Services, Services USA/Healthcare Financial 6th Street Auto Sales Inc. Services AIS Recovery Solutions, LLC A & B Automotive Center Inc Accounts Management Inc. AIS Recovery Solutions, LLC A & P Auto Sales Accounts Receivable AKA Wireless III Inc DBA Z Automated Solutions Inc. Wireless A.R.C. Accounts Recovery (U.S.A.) Corporation LLC Accounts Receivable Alan Gray Inc. Management, Inc. AAA Recovery Systems, Inc. Alberts & Associates Aargon Collection Agency Accredited Collection Services, Albia Motor Co Inc DBA Inc. Chariton Ford Aaron's Sales & Lease Ownership Accretive Health, Inc. DBA Alco Capital Group Medical Financial Solutions AB Auto All Cellular Corporation DBA Accurate Financial Partners Inc Wireless Zone ABC Trucks Activate Financial, LLC All Iowa Products, LLC Abendroth and Russell, P.C. Adel Chrysler, Inc. All Used Cars LLC Ability Recovery Services, LLC Admin Recovery LLC Allegro Acceptance Absolute Collections Corporation Adsen & Associates, LLC Alleman Car Corner Absolute Used Cars Advanced Automotive Alliance Asset Management, Inc. AC Autopay LLC dba Autopay Advanced Call Center Technologies, LLC Services Alliance Collection Agencies, Advantage Collection Inc. -

NHADA Virtual 2020 Business Conference & Partner Expo Selling

Drive: NH Nº 10 VOL 2 Issue 5 2020 NHADA A PUBLICATION OF THE NEW NHADA VIRTUAL 2020 HAMPSHIRE AUTOMOBILE BUSINESS CONFERENCE DEALERS ASSOCIATION & PARTNER EXPO Selling Vehicle Insurance Policies at Save The Date: NHADA Your Dealership? Be Cautious, Says the Virtual 2020 Business NH Insurance Department Conference & Partner Expo During this past legislative session, NHADA, with your This year’s business conference help, successfully defeated a bad piece of legislation & partner expo will be held on that would have significantly hampered your ability. November 2-November 12 online. Read more on p. 10 Read more on p. 11 Quick quotes while your customer is in the showroom. No more need to make multiple calls to wholesalers, and no more waiting for them All brands, models, years, and conditions considered. to get back to you with a price. We do We’re check writers for all powersports vehicles. quotes within minutes, allowing you to put No need to deliver; we’ll pick it up. a deal together while your customer is at your dealership. Quotes done online and/or by phone. If you have questions or would rather get a quote over the phone give us a call at: We are currently able to serve dealerships in NH, ME, MA, VT, NY, CT, RI, and NJ. If you are outside these areas feel free to call us at the number listed above. Auto Auction of New England Oering Six Dealer Consignment & Fleet Lease Lanes In House Transportation Department, Reconditioning and Mechanical We welcome you to Join us to Experience a New Standard in Auction Excellence 8 Action Boulevard, Londonderry NH 03053 • Phone (603) 437-5700 • Visit us at AANE.com DRIVE 11 This year’s business conference & partner expo will be held on November 2-November 12 online. -

Unclaimed Funds Creditor Balance US Bankruptcy Court

Unclaimed Funds Creditor Balance U.S. Bankruptcy Court - District of Louisiana Middle Tuesday, July 01, 2014 Case NumberDebtor Name Division Last Activity Date 00-10056 John F. Pollmeier 3 10/16/2006 Name Amount Date Paid Fund NACC assignee of Discover Financial $363.51 6133BK 00-10180 Debra L. Haskew 3 11/28/2007 Name Amount Date Paid Fund Anesthesiology Consultants $161.55 6133BK First National Bank of Gonzales $32.18 6133BK 00-10181 Ronald Ray White 3 4/26/2007 Name Amount Date Paid Fund Baton Rouge teachers FCU $52.97 6133BK BellSouth Telecommunications, Inc. $110.42 6133BK 00-10284 James Glenn Shafer 3 4/26/2007 Name Amount Date Paid Fund Hancock Bank $203.97 6133BK 00-10345 Terrie C. Reed 3 10/16/2006 Name Amount Date Paid Fund Capital One Financial $43.89 6133BK 00-10389 Ernest C. Bynum 3 4/26/2007 Name Amount Date Paid Fund American Bank Trust Company $552.52 6133BK 00-10452 Daniel K. Arnold 3 5/16/2008 Name Amount Date Paid Fund Axsys National Bank $31.28 6133BK CitiFinancial $174.45 1/21/2004 6047BK Merrick Bank $82.34 6133BK 00-10474 Glenda J. Smith 3 10/16/2006 Name Amount Date Paid Fund Mcbee Systems $63.30 6133BK 00-10496 Shanta Patterson 3 5/16/2008 Name Amount Date Paid Fund Shanta I.Alonzo $1,279.23 8/7/2003 6047BK Lowes $26.39 6133BK SMC $13.80 6133BK 00-10527 Robert Lee Wilson, Jr. 3 4/26/2007 Name Amount Date Paid Fund AAFES $207.72 6133BK Axsys National Bank $13.69 6133BK Lane Menorial Hospital $26.71 6133BK Providian National Bank $60.17 6133BK Page 1 of 122 Unclaimed Funds Creditor Balance U.S. -

Nebraska Department of Motor Vehicles Participating Lender ID's

Nebraska Department of Motor Vehicles Participating Lender ID's Lender ID Financial Institution Address City St Zip 40508547 1ST ADVANTAGE FEDERAL CREDIT UNION 110 CYBERNETICS WAY YORKTOWN VA 23693 12469773 1ST FINANCIAL FEDERAL CREDIT UNION 1232 WENTZVILLE PKWY WENTZVILLE MO 63385 26802365 1ST MIDAMERICA CREDIT UNION PO BOX 210 BETHALTO IL 62010 42389658 1ST UNITED SERVICES CU 5901 GIBRALTAR DR PLEASANTON CA 94588 11035268 360 EQUIPMENT FINANCE LLC 300 BEARDSLEY LN BLDG D-201 AUSTIN TX 78746 94305284 360 FEDERAL CREDIT UNION PO BOX 273 WINDSOR LOCKS CT 06096 20148596 4FRONT CREDIT UNION PO BOX 795 TRAVERSE CITY MI 49685 20907485 5 STAR COMMUNITY CREDIT UNION 1005 CHERRY ST MT PLEASANT IA 52641 21347780 510 NOVA LLC PO BOX 164843 FORT WORTH TX 76161 11685478 A+ FEDERAL CREDIT UNION PO BOX 14867 AUSTIN TX 78761 4867 33185965 AAA FEDERAL CREDIT UNION PO BOX 3788 SOUTH BEND IN 46619 22214719 AAC CREDIT UNION 215 EAST 25TH ST HOLLAND MI 49423 20125256 ABBOTT LABORATORIES EMPL CU (ALEC) 325 TRI-STATE PKWY GURNEE IL 60031 44714700 ABC BUS LEASING INC 1506 30TH ST NW FARIBAULT MN 55021 98366901 ABERDEEN FEDERAL CU PO BOX 1495 ABERDEEN SD 57402 1495 18667854 ABERDEEN PROVING GROUND FEDERAL CU PO BOX 1176 ABERDEEN MD 21001 26378954 ABLE INC PO BOX 1907 AUSTIN TX 78767 44769856 ACA DBA AUTO FINANCE PO BOX 4419 WILMINGTON OH 45177 4419 94219879 ACADEMY BANK NA 1111 MAIN ST STE 200 KANSAS CITY MO 64105 21702589 ACCENTRA CREDIT UNION 400 4TH AVE NE PO BOX 657 AUSTIN MN 55912 22258417 ACCEPTANCE LOAN COMPANY INC PO BOX 9219 MOBILE AL 36691 170442 ACCESS BANK 8712 W DODGE RD OMAHA NE 68114 21598741 ACCESS COMMERCIAL CAPITAL LLC 3000 MARCUS AVE STE 3E01 LAKE SUCCESS NY 11042 41294875 ACCLAIM FEDERAL CREDIT UNION 1823 BANKING ST GREENSBORO NC 27408 20366875 ACE MOTOR ACCEPTANCE CORP. -

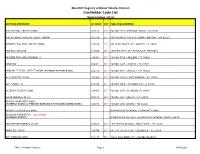

Lienholder Code List September 2020

MassDOT-Registry of Motor Vehicles Division LienHolder Code List September 2020 LIENHOLDER NAME LH CODE ELT MAILING ADDRESS 360 FEDERAL CREDIT UNION C02166 ELT PO BOX 273 / WINDSOR LOCKS / CT 06096 600 ATLANTIC FEDERAL CREDIT UNION C01314 ELT 600 ATLANTIC AVE 4TH FLOOR / BOSTON / MA 02210 ABBOTT LABS EMPL CREDIT UNION C13286 ELT 401 N RIVERSIDE ST / GURNEE / IL 60031 ABC BUS LEASING C41552 ELT 1506 NW 30TH ST / FARIBAULT/ MN 55021 ABILENE TEACHERS FEDERAL CU C06969 ELT PO BOX 5706 / ABILENE / TX 79608 ABLE INC C50051 ELT PO BOX 1907 / AUSTIN / TX 78767 ABOUND FEDERAL CREDIT UNION (FORMERLY FORT KNOX FCU) C02772 ELT PO BOX 900 / RADCLIFF / KY 40159 ACCLAIM FED CR UN C31308 ELT PO BOX 29527 / GREENSBORO / NC 27420 ACF FINCO 1 LP C42336 ELT PO BOX 2969 / SPRINGFIELD / IL 62708 ACHIEVA CREDIT UNION C34463 ELT PO BOX 1500 / DUNEDIN /FL 34697 ACMG FEDERAL CR UN C00716 ELT PO BOX 188 / SOLVAY / NY 13209 ADAMS COMMUNITY BANK (FORMERLY ADAMS COOPERATIVE BANK AND SOUTH ADAMS SAVINGS BANK) C01872 ELT PO BOX 306 / ADAMS / MA 01220 ADAMS COOPERATIVE BANK NOW KNOWN AS ADAMS COMMUNITY BANK ADDISON AVENUE FCU (ALL TITLES) (FORMERLY HPEFCU) NOW KNOWN AS FIRST TECHNOLOGY FEDERAL CREDIT UNION ADVANTAGE FEDERAL CR UN C41514 ELT 1975 BUFFALO ROAD / ROCHESTER / NY 14624 AERO FED CR UN C38764 ELT 5811 W TALAVI BLVD / GLENDALE / AZ 85306 AFC FUNDING CORP C41145 ELT 11299 N ILLINOIS ST / CARMEL IN 46032 RMV - Lienholder Code List Page 1 10/14/2020 MassDOT-Registry of Motor Vehicles Division LienHolder Code List September 2020 LIENHOLDER NAME LH CODE ELT MAILING -

E-Title Certified Lienholders* Lienholder Idlienholder Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City State Zip Code 540623618001St Advantage FCU P.O

Texas Department of Motor Vehicle Registration and Title System e-Title Certified Lienholders* Lienholder IDLienholder Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 City State Zip Code 540623618001st Advantage FCU P.O. Box 2116 Newport News VA 23609 750873880001ST Community FCU 3505 Wildewood Drive San Angelo TX 76904 460133740001st Financial Bank USA 47 Sherman Hill Rd Woodbury TX 06798 370580723001st MidAmerica Credit Union 731 E Bethalto Dr Bethalto IL 62010 9522491920020th Century Fox FCU PO Box 641849 Los Angeles CA 90064 27250498200360 Equipment Finance, LLC 300 Beardsley Lane Building D Suite 201 Austin Tx 78745 06067454100360 Federal Credit Union 191 Ella Grasso Turnpike Windsor Locks CT 06096 381524350004Front Credit Union PO Box 795 Traverse City MI 49685 82531214500777 Equipment Finance LLC 600 Brickell Ave 19th Floor Miami FL 33131 81376585600A Plus Finance PO Box 4136 McAllen TX 78502 74117864800A+ Federal Credit Union PO Box 14867 Austin TX 78761 82374905500AAB-CADI LLC 12001 SW 128th Ct Ste 106 Miami FL 33186 38029964300AAC Credit Union 177 Wilson Ave NW Grand Rapids MI 49534 11601490300AAFCU PO Box 619001 MD#2100 DFW Airport TX 752619001 75605437700AAFES Federal Credit Union PO Box 210708 Dallas TX 75211 52063737400Aberdeen Proving Ground Fed CU PO Box 1176 Aberdeen MD 21001 75088886000Abilene Teachers FCU PO Box 5706 Abilene TX 796085706 61054906800Abound Federal Credit Union PO Box 900 Radcliff KY 40159 83228040400ABT Keystone Auto Lending LLC 140 Intracoastal Pointe Dr Ste 212 Jupiter FL 33477 84056779600Academy Bank, N.A. 1111 Main St., Ste 202 Kansas City MO 64105 63113138100Acceptance Loan Company Inc PO Box 9219 Mobile AL 36691 26137562200Access Bank 210 N. -

Office of the Special Inspector General for the Troubled Asset Relief Program

SIGTARP: Quarterly Report to Congress | January 26, 2012 | January 26, Congress to Quarterly Report SIGTARP: NSPECTOR L I GE IA NE C R E A P L S T R M O A U R B G L O ED R A F P SSET RELIE Office of the Special Inspector General Q1 for the Troubled Asset Relief Program SIGTARPSIGTARP 2012 SIGTARPSIGTARP Advancing Economic Stability Through Transparency, Coordinated Oversight and Robust Enforcement SIG-QR-12-01 202.622.1419 Hotline: 877.SIG.2009 Quarterly Report to Congress [email protected] January 26, 2012 www.SIGTARP.gov MISSION SIGTARP’s mission is to advance economic stability by promoting the efficiency and effectiveness of TARP management, through transparency, through coordinated oversight, and through robust enforcement against those, whether inside or outside of Government, who waste, steal or abuse TARP funds. STATUTORY AUTHORITY SIGTARP was established by Section 121 of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (“EESA”) and amended by the Special Inspector General for the Troubled Asset Relief Program Act of 2009 (“SIGTARP Act”). Under EESA and the SIGTARP Act, the Special Inspector General has the duty, among other things, to conduct, supervise and coordinate audits and investigations of any actions taken under the Troubled Asset Relief Program (“TARP”) or as deemed appropriate by the Special Inspector General. In carrying out those duties, SIGTARP has the authority set forth in Section 6 of the Inspector General Act of 1978, including the power to issue subpoenas. Office of the Special Inspector General for the -

Outside Oklahoma

Oklahoma Department of Consumer Credit * 3613 NW 56th Street, Suite 240 * Oklahoma City, OK 73112-4512 Phone: (405) 521-3653 * Fax: (405) 521-6740 * Toll Free: (800) 448-4904 * Website: http://www.ok.gov/okdocc Total number of active, licensed Notifications: 239 Oklahoma Department of Consumer Credit License Roster - Notification - Outside Oklahoma Each business on this list holds an active license as of: Monday, Feb 12, 2018 State: OK City: Tulsa 87443 Oak Creek Home Center Issue Date 11/9/2017 Nationwide Housing Systems, LLC 11306 E. Admiral Place Expire Date 1/31/2019 2450 South Shore Blvd Craig Reynolds Suite 300 Tulsa, OK 74116 League City TX 77573 (281) 334-9700 Phone: (281) 334-9700 Corp Phone (281) 334-9700 Corp Fax (281) 334-3408 Fax: (281) 334-3408 Corporate Website oakcreekhomes.com State: AL City: Mobile 84449 Southeast Toyota Finance Issue Date 1/31/2011 Southeast Toyota Finance 6150 Omni Park Drive Expire Date 1/31/2019 190 Jim Moran Blvd. World Omni Financial Cor Mobile, AL 36609 Deerfield Beach FL 33442 (954) 420-4604 Phone: (954) 420-4604 Corp Phone (954) 420-4604 Corp Fax (954) 363-4126 Fax: (954) 363-4126 Corporate Website WWW.MYWORLDOMNI.COM 84451 VTX Inc. As Trustee Of World Omni LT Issue Date 1/31/2011 Vtx Inc. As Trustee Of World Omni Lt 6150 Omni Park Drive Expire Date 1/31/2019 190 Jim Moran Blvd Patricia M Child Mobile, AL 36609 Deerfield Beach FL 33442 (954) 420-4604 Phone: (954) 420-4604 Corp Phone (954) 420-4604 Corp Fax (954) 363-4126 Fax: (954) 363-4126 State: AR City: Bentonville 84170 Car-Mart Issue Date 11/2/2010 Car-mart 802 S E Plaza Ave Ste 200 Expire Date 1/31/2019 802 S E Plaza Ave Ste 200 America's Car-mart, Inc. -

Bmv Ohio-ELT-Participant-List.Pdf

Ohio ELT Participants ELH Code Lienholder Name Street Address City State Zip Code Trans Code Mailbox Name E01685 1ST ADVANTAGE FEDERAL CREDIT UNION P O BOX 2116 NEWPORT NEWS VA 23609 A FDI E02361 1ST BANK YUMA 2799 S. 4TH AVENUE YUMA AZ 85364 VINTEK E11956 1ST FINANCIAL BANK USA 47 SHERMAN HILL ROAD WOODBURY CT 6798 DDI E08693 AAC CREDIT UNION 215 EAST 25TH STREET HOLLAND MI 49423 A DDI E11989 ABBEY CREDIT UNION, INC. 800 FALLS CREEK DRIVE VANDALIA OH 45377 A FDI E02664 ABBOTT LABORATORIES EMPLOYEES C U 325 TRI‐STATE PARKWAY GURNEE IL 60031 A DDI E09223 ACADEMY BANK, N.A. 1111 MAIN ST. STE 202 KANSAS CITY MO 64105 A VINTEK E08479 ACCEPTANCE LOAN COMPANY, INC. PO BOX 9219 MOBILE AL 36691 A DDI E09379 ACCLAIM FEDERAL CREDIT UNION PO BOX 29527 GREENSBORO NC 27408 A FDI E11653 ACME FEDERAL CREDIT UNION 34799 B CURTIS BLVD EASTLAKE OH 44095 A VINTEK E05320 ADVANCE AMERICA, CASH ADVANCE CENTE 606 TAYWOOD RD., STE 5A ENGLEWOOD OH 45322 A DDI E05375 ADVANCE AMERICA, CASH ADVANCE CENTE 2039 E. DOROTHY LANE KETTERING OH 45420 A DDI E05386 ADVANCE AMERICA, CASH ADVANCE CENTE 999 S. MAIN ST. CENTERVILLE OH 45458 A DDI E04363 ADVANCED CAR COMPANY 10000 N 31ST AVE, SUITE C250 PHOENIX AZ 85051 A VINTEK E11428 ADVANTAGE ONE CREDIT UNION 23670 TELEGRAPH RD BROWNSTOWN MI 48134 A FDI E10449 ADVANZ CREDIT UNION 9600 ORMSBY STATION RD LOUISVILLE KY 40223 A FDI E00594 AERO FEDERAL CREDIT UNION 18301 N 79TH AVE A‐100 GLENDALE AZ 85308 A VINTEK E01517 AERO FEDERAL CREDIT UNION 5811 TALAVI BLVD GLENDALE AZ 85306 A VINTEK E08491 AFFINITY GROUP CREDIT UNION 144 E PIKE ST PONTIAC MI 48342 A DDI E10359 AFGM ENTERPRISES FCU 132 CAYUGA ROAD CHEEKTOWAGA NY 14225 A FDI E04105 AFLAC FEDERAL CREDIT UNION 1932 WYNNTON ROAD COLUMBUS GA 31999 A VINTEK E02440 AGRICULTURE FEDERAL CREDIT UNION P O BOX 2225 MERRIFIELD VA 22116 A FDI E05713 AIR ACADEMY FEDERAL CREDIT UNION 9810 NORTH UNION BLVD. -

Sigtarp0424.Pdf

MISSION SIGTARP’s Mission is to advance economic stability by promoting the efficiency and effectiveness of TARP management, through transparency, through coordinated oversight, and through robust enforcement against those, whether inside or outside of Government, who waste, steal, or abuse TARP funds. STATUTORY AUTHORITY SIGTARP was established by Section 121 of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (“EESA”) and amended by the Special Inspector General for the Troubled Asset Relief Program Act of 2009 (“SIGTARP Act”). Under EESA and the SIGTARP Act, the Special Inspector General has the duty, among other things, to conduct, supervise, and coordinate audits and investigations of any actions taken under the Troubled Asset Relief Program (“TARP”) or as deemed appropriate by the Special Inspector General. In carrying out those duties, SIGTARP has the authority set forth in Section 6 of the Inspector General Act of 1978, including the power to issue subpoenas. Office of the Special Inspector General for the Troubled Asset Relief Program General Telephone: 202.622.1419 Hotline: 877.SIG.2009 [email protected] www.SIGTARP.gov CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Oversight Activities of SIGTARP 8 SIGTARP Recommendations on the Operation of TARP 9 Report Organization 10 Section 1 THE OFFICE OF THE SPECIAL INSPECTOR GENERAL FOR THE TROUBLED ASSET RELIEF PROGRAM 11 SIGTARP Creation and Statutory Authority 13 SIGTARP Oversight Activities Since the January 2012 Quarterly Report 13 The SIGTARP Organization 25 Section 2 TARP OVERVIEW 27 TARP Funds Update 29 Financial Overview of TARP 33 Housing Support Programs 54 Financial Institution Support Programs 78 Asset Support Programs 117 Automotive Industry Support Programs 135 Executive Compensation 142 Section 3 TARP AND SBLF: IMPACT ON COMMUNITY BANKS 145 Introduction 147 The U.S.