Production of Coffee in Mysore and Coorg in the Nineteenth Century1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report

Karnataka Tourism Vision group 2014 report KARNATAKA TOURISM VISION GROUP (KTVG) Recommendations to the GoK: Jan 2014 Task force KTVG Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report 1 FOREWORD Tourism matters. As highlighted in the UN WTO 2013 report, Tourism can account for 9% of GDP (direct, indirect and induced), 1 in 11 jobs and 6% of world exports. We are all aware of amazing tourist experiences globally and the impact of the sector on the economy of countries. Karnataka needs to think big, think like a Nation-State if it is to forge ahead to realise its immense tourism potential. The State is blessed with natural and historical advantage, which coupled with a strong arts and culture ethos, can be leveraged to great advantage. If Karnataka can get its Tourism strategy (and brand promise) right and focus on promotion and excellence in providing a wholesome tourist experience, we believe that it can be among the best destinations in the world. The impact on job creation (we estimate 4.3 million over the next decade) and economic gain (Rs. 85,000 crores) is reason enough for us to pay serious attention to focus on the Tourism sector. The Government of Karnataka had set up a Tourism Vision group in Oct 2013 consisting of eminent citizens and domain specialists to advise the government on the way ahead for the Tourism sector. In this exercise, we had active cooperation from the Hon. Minister of Tourism, Mr. R.V. Deshpande; Tourism Secretary, Mr. Arvind Jadhav; Tourism Director, Ms. Satyavathi and their team. The Vision group of over 50 individuals met jointly in over 7 sessions during Oct-Dec 2013. -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

PART 1 of Volume 13:6 June 2013

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 13:6 June 2013 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Contents Drama in Indian Writing in English - Tradition and Modernity ... 1-101 Dr. (Mrs.) N. Velmani Reflection of the Struggle for a Just Society in Selected Poems of Niyi Osundare and Mildred Kiconco Barya ... Febisola Olowolayemo Bright, M.A. 102-119 Identity Crisis in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake ... Anita Sharma, M.Phil., NET, Ph.D. Research Scholar 120-125 A Textual Study of Context of Personal Pronouns and Adverbs in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” ... Fadi Butrus K Habash, M.A. 126-146 Crude Oil Price Behavior and Its Impact on Macroeconomic Variable: A Case of Inflation ... M. Anandan, S. Ramaswamy and S. Sridhar 147-161 Using Exact Formant Structure of Persian Vowels as a Cue for Forensic Speaker Recognition ... Mojtaba Namvar Fargi, Shahla Sharifi, Mohammad Reza Pahlavan-Nezhad, Azam Estaji, and Mehi Meshkat Aldini Ferdowsi University of Mashhad 162-181 Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 13:6 June 2013 Contents List i Simplification of CC Sequence of Loan Words in Sylheti Bangla ... Arpita Goswami, Ph.D. Research Scholar 182-191 Impact of Class on Life A Marxist Study of Thomas Hardy’s Novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles .. -

Mysore Tourist Attractions Mysore Is the Second Largest City in the State of Karnataka, India

Mysore Tourist attractions Mysore is the second largest city in the state of Karnataka, India. The name Mysore is an anglicised version of Mahishnjru, which means the abode of Mahisha. Mahisha stands for Mahishasura, a demon from the Hindu mythology. The city is spread across an area of 128.42 km² (50 sq mi) and is situated at the base of the Chamundi Hills. Mysore Palace : is a palace situated in the city. It was the official residence of the former royal family of Mysore, and also housed the durbar (royal offices).The term "Palace of Mysore" specifically refers to one of these palaces, Amba Vilas. Brindavan Gardens is a show garden that has a beautiful botanical park, full of exciting fountains, as well as boat rides beneath the dam. Diwans of Mysore planned and built the gardens in connection with the construction of the dam. Display items include a musical fountain. Various biological research departments are housed here. There is a guest house for tourists.It is situated at Krishna Raja Sagara (KRS) dam. Jaganmohan Palace : was built in the year 1861 by Krishnaraja Wodeyar III in a predominantly Hindu style to serve as an alternate palace for the royal family. This palace housed the royal family when the older Mysore Palace was burnt down by a fire. The palace has three floors and has stained glass shutters and ventilators. It has housed the Sri Jayachamarajendra Art Gallery since the year 1915. The collections exhibited here include paintings from the famed Travancore ruler, Raja Ravi Varma, the Russian painter Svetoslav Roerich and many paintings of the Mysore painting style. -

Mehendale Book-10418

Tipu as He Really Was Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale Tipu as He Really Was Copyright © Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale First Edition : April, 2018 Type Setting and Layout : Mrs. Rohini R. Ambudkar III Preface Tipu is an object of reverence in Pakistan; naturally so, as he lived and died for Islam. A Street in Islamabad (Rawalpindi) is named after him. A missile developed by Pakistan bears his name. Even in India there is no lack of his admirers. Recently the Government of Karnataka decided to celebrate his birth anniversary, a decision which generated considerable opposition. While the official line was that Tipu was a freedom fighter, a liberal, tolerant and enlightened ruler, its opponents accused that he was a bigot, a mass murderer, a rapist. This book is written to show him as he really was. To state it briefly: If Tipu would have been allowed to have his way, most probably, there would have been, besides an East and a West Pakistan, a South Pakistan as well. At the least there would have been a refractory state like the Nizam's. His suppression in 1792, and ultimate destruction in 1799, had therefore a profound impact on the history of India. There is a class of historians who, for a long time, are portraying Tipu as a benevolent ruler. To counter them I can do no better than to follow Dr. R. C. Majumdar: “This … tendency”, he writes, “to make history the vehicle of certain definite political, social and economic ideas, which reign supreme in each country for the time being, is like a cloud, at present no bigger than a man's hand, but which may soon grow in volume, and overcast the sky, covering the light of the world by an impenetrable gloom. -

History) (M.A.History)

Directorate of Distance Education J.R.N. Rajasthan Vidyapeeth University Pratap Nagar, Udaipur Course Structure & Syllabus For MASTER OF ARTS (HISTORY) (M.A.HISTORY) 1 COURSE STRUCTURE SECOND YEAR: (FINAL) Code Course Title Credits MAHIS16 Historical Method and Historiography 7 MAHIS17 History of India (1526 to 1707) 7 MAHIS18 History of the Wodeyars of Mysore (1500 to 1956) 7 MAHIS19 History of Freedom Movement in India (1885-1947_ 7 MAHIS20 History of United States of America (1765-1990) 7 2 SYLLABUS (FINAL YEAR) MAHIS16: Historical Method and Historiography BLOCK 1: UNIT 1: Meaning and Definitions – Nature and Scope of History 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Meaning and Definition 1.3 Nature of History 1.4 Scope of History 1.5 Let us sum up 1.6 Self Assessment Questions 1.7 Selected Bibliography UNIT 2: Subject Matter of History and kinds of History 2.0 Objectives 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Subject Matter of History 2.3 Kinds of History 2.4 Let us sum up 2.5 Self Assessment Questions 2.6 Books for further study UNIT 3: Purpose (Aims) and uses of History 3.0 Objectives 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Purpose (Aims) of History 3.3 Uses of History 3.4 Let us sum up 3.5 Self Assessment questions 3.6 Bibliography 3 UNIT 4: History and the relations with social science and other sciences 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 History and its relations with social sciences 4.2.1 History and Geography 4.2.2 History and political science 4.2.3 History and Economics 4.2.4 History and Sociology 4.2.5 History and Psychology 4.2.6 History and Ethics 4.2.7 History -

MEDIA Handbook 2018

MEDIA hAnDbook 2018 Information & Public Relations Department Government of Kerala PERSONAL MEMORANDA Name................................................................................... Address Office Residence .......................... ............................... .......................... ............................... .......................... ............................... .......................... ............................... .......................... ............................... MEDIA HANDBOOK 2018 .......................... ............................... Information & Public Relations Department .......................... ............................... Government of Kerala Telephone No. Office ............................................... Chief Editor T V Subhash IAS Mobile ............................................... Co-ordinating Editor P Vinod Fax ............................................... Deputy Chief Editor K P Saritha E-mail ............................................... Editor Manoj K. Puthiyavila Residence ............................................. Editorial assistance Priyanka K K Nithin Immanuel Vehicle No .......................................................................... Gautham Krishna S Driving Licence No .............................................................. Ananthan R M Expires on . .......................................................................... Designer Ratheesh Kumar R Accreditation Card No ........................ Date....................... Circulation -

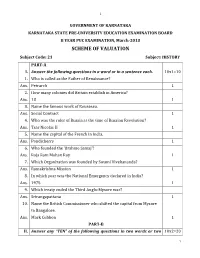

SCHEME of VALUATION Subject Code: 21 Subject: HISTORY PART-A I

1 GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA KARNATAKA STATE PRE-UNIVERSITY EDUCATION EXAMINATION BOARD II YEAR PUC EXAMINATION, March-2013 SCHEME OF VALUATION Subject Code: 21 Subject: HISTORY PART-A I. Answer the following questions in a word or in a sentence each. 10x1=10 1. Who is called as the Father of Renaissance? Ans. Petrarch 1 2. How many colonies did Britain establish in America? Ans. 13 1 3. Name the famous work of Rousseau. Ans. Social Contract 1 4. Who was the ruler of Russia at the time of Russian Revolution? Ans. Tsar Nicolas II 1 5. Name the capital of the French in India. Ans. Pondicherry 1 6. Who founded the ‘Brahmo Samaj’? Ans. Raja Ram Mohan Roy 1 7. Which Organization was founded by Swami Vivekananda? Ans. Ramakrishna Mission 1 8. In which year was the National Emergency declared in India? Ans. 1975 1 9. Which treaty ended the Third Anglo-Mysore war? Ans. Srirangapattana 1 10. Name the British Commissioner who shifted the capital from Mysore to Bangalore. Ans. Mark Cubbon 1 PART-B II. Answer any “TEN” of the following questions in two words or two 10x2=20 1 2 sentences each: 11. Who circumnavigated the earth for the first time? Which country did he belong to? Ans. Ferdinand Magellan– Portugal / Spain 1+1 12. Mention the three important watchwords of French Revolution. Ans. Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. 1+1 13. Name the architect of German Unification. Which policy did he follow? Ans. Bismark – Blood & Iron. 1+1 14. What Is ‘Great Leap Forward’? Who introduced it? Ans. -

Tipu Sultan's Mission to the Ottoman Empire

American International Journal of Available online at http://www.iasir.net Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences ISSN (Print): 2328-3734, ISSN (Online): 2328-3696, ISSN (CD-ROM): 2328-3688 AIJRHASS is a refereed, indexed, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary and open access journal published by International Association of Scientific Innovation and Research (IASIR), USA (An Association Unifying the Sciences, Engineering, and Applied Research) Seeking an Ally against British Expansion in India: Tipu Sultan’s Mission to the Ottoman Empire Emre Yuruk Research Scholar, Centre for West Asian Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, 110067, INDIA Abstract: After British defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588, they emerged as a new power in Europe and expanded its sovereignty all over the world by controlling overseas trade gradually. They aimed to take advantage of the wealth of India thanks to East India Company starting from 17th century and in time; they established their hegemony in the Indian subcontinent. When Tipu Sultan the ruler of Mysore realised this colonial intention of British over India in the second half of 18th century, he wanted to remove them from India. However, the support that Tipu Sultan needed was not given by Indian local rulers Mughals, Nizam and Marathas. Thus, Tipu Sultan turned his policy to the Ottoman Empire. He sent a mission to Constantinople with some valuable gifts to take Ottoman’s assistance against British. The proposed paper analyses the correspondences of Tipu Sultan and Ottoman Sultans Abdulh amid I and Selim III and how British superior diplomacy dealt with French, the Ottomans and Indian native rulers to suppress Tipu Sultan from accumulating power as well as to stop him from making any alliances to the detriment of British interest. -

THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY of INDIA Indian Society and The

THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA Indian society and the making of the British Empire Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA General editor GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Associate editors CA. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine's College and JOHN F. RICHARDS Professor of History, Duke University Although the original Cambridge History of India, published between 1922. and 1937, did much to formulate a chronology for Indian history and de- scribe the administrative structures of government in India, it has inevitably been overtaken by the mass of new research published over the last fifty years. Designed to take full account of recent scholarship and changing concep- tions of South Asia's historical development, The New Cambridge History of India will be published as a series of short, self-contained volumes, each dealing with a separate theme and written by a single person. Within an overall four-part structure, thirty-one complementary volumes in uniform format will be published. As before, each will conclude with a substantial bib- liographical essay designed to lead non-specialists further into the literature. The four parts planned are as follows: I The Mughals and their contemporaries II Indian states and the transition to colonialism III The Indian Empire and the beginnings of modern society IV The evolution of contemporary South Asia A list of individual titles in preparation will be found at the end of the volume. -

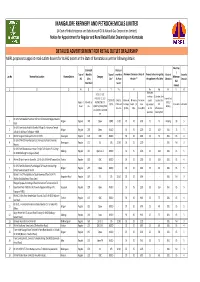

Final for Advertisement.Xlsx

MANGALORE REFINERY AND PETROCHEMICALS LIMITED (A Govt of India Enterprise and Subsidiary of Oil & Natural Gas Corporation Limited) Notice for Appointment for Regular and Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships in Karnataka DETAILED ADVERTISEMENT FOR RETAIL OUTLET DEALERSHIP MRPL proposes to appoint retail outlets dealers for its HiQ outlets in the State of Karnataka as per the following details: Fixed Fee Estimated Rent per / Type of Monthly Type of month in Minimum Dimension /Area of Finance to be arranged by Mode of Security Loc.No Name of the Location Revnue District Category Minimum RO Sales Site* Rs.P per the site ** the applicant in Rs Lakhs Selection Deposit Bid Potential # Sq.mt amount 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 7A 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 Estimated SC/SC CC-1/SC working Estimated fund PH/ST/ST CC-1/ST Draw of Lots CODO/DOD Only for Minimum Minimum Minimum capital required for Regular / MS+HSD in PH/OBC/OBC CC- (DOL) / O/CFS CODO and Frontage Depth (in Area requirement RO in Rs Lakhs in Rs Lakhs Rural KLs 1/OBC PH/OPEN/OPEN Bidding CFS sites (in Mts) Mts) (in Sq.Mts) for RO infrastructure CC-1/OPEN CC-2/OPEN operation development PH On LHS From Mezban Function Hall To Indal Circle On Belgavi Bauxite 1 Belgavi Regular 240 Open CODO 51.00 20 20 600 25 15 Bidding 30 5 Road On LHS From Kerala Hotel In Biranholi Village To Hanuman Temple 2 Belgavi Regular 230 Open DODO - 35 35 1225 25 100 DOL 15 5 ,Ukkad On Kolhapur To Belgavi - NH48 3 Within Tanigere Panchayath Limit On SH 76 Davangere Regular 105 OBC DODO - 30 30 900 25 75 DOL 15 4 On LHS Of NH275 From Byrapatna (Channapatna Taluk) Towards 4 Ramnagara Regular 171 SC CFS 22.90 35 35 1225 - - DOL Nil 3 Mysore On LHS From Sharanabasaveshwar Temple To St Xaviers P U College 5 Kalburgi Regular 225 Open CC-1 DODO - 35 35 1225 25 100 DOL 15 5 On NH50 (Kalburgi To Vijaypura Road) 6 Within 02 Kms From Km Stone No. -

Heritage of Mysore Division

HERITAGE OF MYSORE DIVISION - Mysore, Mandya, Hassan, Chickmagalur, Kodagu, Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Chamarajanagar Districts. Prepared by: Dr. J.V.Gayathri, Deputy Director, Arcaheology, Museums and Heritage Department, Palace Complex, Mysore 570 001. Phone:0821-2424671. The rule of Kadambas, the Chalukyas, Gangas, Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas, Vijayanagar rulers, the Bahamanis of Gulbarga and Bidar, Adilshahis of Bijapur, Mysore Wodeyars, the Keladi rulers, Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan and the rule of British Commissioners have left behind Forts, Magnificient Palaces, Temples, Mosques, Churches and beautiful works of art and architecture in Karnataka. The fauna and flora, the National parks, the animal and bird sanctuaries provide a sight of wild animals like elephants, tigers, bisons, deers, black bucks, peacocks and many species in their natural habitat. A rich variety of flora like: aromatic sandalwood, pipal and banyan trees are abundantly available in the State. The river Cauvery, Tunga, Krishna, Kapila – enrich the soil of the land and contribute to the State’s agricultural prosperity. The water falls created by the rivers are a feast to the eyes of the outlookers. Historical bakground: Karnataka is a land with rich historical past. It has many pre-historic sites and most of them are in the river valleys. The pre-historic culture of Karnataka is quite distinct from the pre- historic culture of North India, which may be compared with that existed in Africa. 1 Parts of Karnataka were subject to the rule of the Nandas, Mauryas and the Shatavahanas; Chandragupta Maurya (either Chandragupta I or Sannati Chandragupta Asoka’s grandson) is believed to have visited Sravanabelagola and spent his last years in this place.