Television's Role in Indian New Screen Ecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL Millenniumpost.In

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL millenniumpost.in pages millenniumpost NO HALF TRUTHS th28 NEW DELHI & KOLKATA | MAY 2018 Contents “Dharma and Dhamma have come home to the sacred soil of 63 Simplifying Doing Trade this ancient land of faith, wisdom and enlightenment” Narendra Modi's Compelling Narrative 5 Honourable President Ram Nath Kovind gave this inaugural address at the International Conference on Delineating Development: 6 The Bengal Model State and Social Order in Dharma-Dhamma Traditions, on January 11, 2018, at Nalanda University, highlighting India’s historical commitment to ethical development, intellectual enrichment & self-reformation 8 Media: Varying Contours How Central Banks Fail am happy to be here for 10 the inauguration of the International Conference Unmistakable Areas of on State and Social Order 12 Hope & Despair in IDharma-Dhamma Traditions being organised by the Nalanda University in partnership with the Vietnam The Universal Religion Buddhist University, India Foundation, 14 of Swami Vivekananda and the Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. In particular, Ethical Healthcare: A I must welcome the international scholars and delegates, from 11 16 Collective Responsibility countries, who have arrived here for this conference. Idea of India I understand this is the fourth 17 International Dharma-Dhamma Conference but the first to be hosted An Indian Summer by Nalanda University and in the state 18 for Indian Art of Bihar. In a sense, the twin traditions of Dharma and Dhamma have come home. They have come home to the PMUY: Enlightening sacred soil of this ancient land of faith, 21 Rural Lives wisdom and enlightenment – this land of Lord Buddha. -

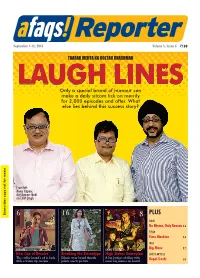

Only a Special Brand of Humour Can Make a Daily Sitcom Tick on Merrily for 2,000 Episodes and After

September 1-15, 2016 Volume 5, Issue 6 `100 TAARAK MEHTA KA OOLTAH CHASHMAH LAUGH LINES Only a special brand of humour can make a daily sitcom tick on merrily for 2,000 episodes and after. What else lies behind this success story? From left: Anooj Kapoor, Asit Kumarr Modi and N P Singh Subscriber copy not for resale Subscriber copy not 6 16 8 PLUS DOVE No Rhyme, Only Reason 12 TITAN Time Machine 14 IKEA NESCAFE MYNTRA CHING’S SECRET Big Move 17 New Cup of Resolve Breaking the Stereotype High Stakes Gameplan GUEST ARTICLE The coffee brand’s ad is back Ethnic wear brand Anouk A big budget ad film with 23 with a warm-up session. paints a new picture. some big names on board. Kopal Doshi editorial This fortnight... Volume 5, Issue 6 EDITOR f you are looking for persistence-leads-to-success stories, they don’t come better Sreekant Khandekar I than this. PUBLISHER September 1-15, 2016 Volume 5, Issue 6 `100 Prasanna Singh TAARAK MEHTA KA OOLTAH CHASHMAH Fourteen years ago, when he first set out visiting broadcasters with script in hand, EXECUTIVE EDITOR Ashwini Gangal LAUGH LINES Asit Kumarr Modi, head of production house Neela Telefilms, was laughed out of Only a special brand of humour can make a daily sitcom tick on merrily PRODUCTION EXECUTIVE for 2,000 episodes and after. What the studios. They wouldn’t touch a script - that did not have television’s staple diet else lies behind this success story? Andrias Kisku of family intrigue or tragedy - with a barge pole. -

Outcome-AGM-2016.Pdf

Spine to be adjusted by printer C-13, Balaji House, Dalia Industrial Estate, Opposite Laxmi Industrial Estate, New Link Road, Andheri (West) Mumbai - 400 053. www.balajitelefilms.com world.com dickenson www. dickenson Spine to be adjusted by printer Spine to be adjusted by printer Spine to be adjusted by printer We are content innovators, creators and producers of unmatched credentials and long-standing success. We operate as a vertically integrated studio model, which allows us to create, distribute and monetise content, not only in ways that are best aligned with viewer preferences, but in ways in which we can capture the maximum value stream. With a focus on chasing quality growth, we continue to create gripping content – content that is relevant to As global viewership diverse sets of audiences and accessible across multiple platforms. continues to evolve, we have With geographical boundaries disappearing in the seamless world of the anticipated future trends and internet, we aim to make our content seamlessly available. Improvement in created new entertainment mobile broadband infrastructure, gradual reduction in cost of internet and paradigms. Today, we increase in smartphone screen sizes is driving consumer preferences. straddle across all the three The Subscription Video on Demand (SVOD) market in India is on the cusp distinct platforms through of a meteoric take-off. As Over The Top (OTT) video consumption continues which people consume to grow tremendously, we are leveraging our capabilities to create content entertainment – across platforms. Our motive is vertical integration across the value chain by Television, offering our own OTT services. We are making our delivery channels more closely aligned to the emerging needs and creating entertainment-on-the-go Movies and for our dynamic audiences. -

Anne Hathaway INTE O Rem D’Souza

PVR MOVIES FIRST VOL. 32 YOUR WINDOW INTO THE WORLD OF CINEMA JUNE 2018 21 LITTLE-KNOWN THINGS ABOUt…. GUEST RVIEW ANNE HATHAWAY INTE O REM D’SOUZA THE BEST NEW MOVIES PLAYING THIS MONTH: VEERE DI WEDDING, RACE 3, ISLE OF DOGS AND SANJU GREETINGS ear Movie Lovers, Motwane’s vigilante drama “Bhavesh Joshi” are among the much-awaited films that hit the screen this month. Here’s the June issue of Movies First, your exclusive window to the world of cinema. Meet rising star John Boyega and join us in wishing Hollywood icon Meryl Streep a happy birthday. Take a peek into Colin Trevorrow’s all-new, edgy “Jurassic World,” while also rewinding to its original “Jurassic World” We really hope you enjoy the issue. Wish you a fabulous (2015) the Steven Spielberg adventure that changed the month of movie watching. face of sci-fi forever. Regards All eyes are on director Remo D’Souza, whose revelations about Salman Khan starrer “Race 3” will get your pulse racing. Raj Kumar Hirani’s biographical film “Sanju”, Kareena Gautam Dutta Kapoor’s boisterous “Veere di Wedding” and Vikramaditya CEO, PVR Limited USING THE MAGAZINE We hope you’ll find this magazine easy to use, but here’s a handy guide to the icons used throughout anyway. You can tap the page once at any time to access full contents at the top of the page. PLAY TRAILER SET REMINDER BOOK TICKETS SHARE PVR MOVIES FIRST PAGE 2 CONTENTS Tap for... Tap for... Movie OF THE MONTH UP CLOSE & PERSONAL Tap for.. -

Bengali Movie Hd 1080P Fida

Bengali Movie Hd 1080p Fida 1 / 4 Bengali Movie Hd 1080p Fida 2 / 4 3 / 4 Dubai Return Movie Download In Hd 1080p. from hippococos ... Fida 2 Telugu Full Movie Free Download Hd ... Page 2. Paa Bengali Movie .... Fida Bengali Full Movie Video Songs Download, Fida Bengali Full Movie, Fida Bengali Full Movie Video MP4, HD MP4, And Watch, Fida Bengali Full Movie .... Click here to watch kurulus Osman Episode 11 with English, Urdu & Bangla ... Click here to Watch & Download Episode in English Subtitles HD 1080, No Ads ... Click here to Watch Full Episode in English Subtitles, 1080p Free of Cost ... I also bring the latest news about Movies and TV Shows that are based on true history.. Eka din faka raat || Fida movie || full HD video song || yash & sanjana. ... Banglar Bou | HD1080p | Ferdous | Moushumi | ATM Shamsuzzaman | Bangla Hit Movie. Fida Full Bangla Movie Hd(ফিদা বাংলা ফুল মুভি) by AHM ALI ... Banglar Bou HD1080p Ferdous Moushumi ATM Shamsuzzaman Bangla Hit Movie by G Series .... Bengali Movie Hd 1080p Fida >>> DOWNLOAD. fd3bc05f4a Bollywood HD Video (640x360) Bengali HD Video . HD Movies: 720p/1080P HD .... #Radha rani kaho to & Abhi jan dedu# full HD bhakti song vikas kumar ... To Abhi movie dubbed bengali, Radha Rane Kaho To Abhi movie dubbed english, ... jhanki Group Sultanpur 1080p, Radha rani kaho to abhi jaan de du .. dance, ... Jis Dil Pe Fida Hai Ek Bewafa Hai · Hame Na Bhulana Sajan Song Movie Name .... Stream and download HD quality popular and hit movies in BENGALI.. Fida ... with HD Quality in. 1080P.Bengali Movies Online, Bengali Movies,Bengali Movies. -

D8A4 E` Ac`SV ?R \R R Reert\

'* ; "<%"= %"== !" RNI Regn. No. MPENG/2004/13703, Regd. No. L-2/BPLON/41/2006-2008 /* 01 2 /!") " # $%& !" !"#$% &$' * 3) ) 34 5)6.33..3 . ) 36 +8 &!&'#(%') )'# ..-8) .3 5) )' !)'# ') , 384 ,.9) 3).) . ))3*75 ** )' !#* )'&' +'*%' ' # $%& ' '(%)*)*+ , -": - .-/ rapes and violence for decades meet Pakistan’s Punjab and the Nankana incident Governor and Chief Minister,” shows how minorities there are he said. Longowal said the del- persecuted and why they need egation will comprise Rajinder citizenship in India. Singh Mehta, Roop Singh, Lekhi also said that this Surjit Singh and Rajinder incident should open the eyes Singh. !"" of Congress leaders such as So- “We have spoken with the nia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi and Gurdwara Nankana Sahib Q ))*+ no borders. Navjot Singh Sidhu, TMC sup- management committee...They Taking to Twitter, Rahul remo Mamata Banerjee, the told us the situation is normal ! he Shiromani Gurdwara termed Friday attack repre- leftists and the “Urban Naxals” now,” Longowal said. # $% TParbhandhak Committee hensible, and said the only who have been opposing the The SGPC chief said the &'() +L (SGPC), the apex body which known antidote to bigotry is amended Citizenship Act. sentiments of the Sikh com- *,- provincial authorities in the - manages Sikh shrines, will love, mutual respect and under- Meanwhile, strongly con- munity were hurt with the Punjab province have informed L send a four-member delegation -

Pay-TV Programmers & Channel Distributors

#GreatJobs C NTENT page 5 www.contentasia.tv l www.contentasiasummit.com Asia-Pacific sports Game over: StarHub replaces Discovery rights up 22% to 7 new channels standby for July rollout in Singapore US$5b in 2018 Digital rights driving inflation, value peaks everywhere except India Demand for digital rights will push the value of sports rights in the Asia-Pacific region (excluding China) up 22% this year to a record US$5 billion, Media Partners Asia (MPA) says in its new re- port, Asia Pacific Sports In The Age of GoneGone Streaming. “While sports remains the last bastion for pay-TV operators com- bating subscriber churn, OTT delivery is becoming the main driver of rights infla- tion, opening up fresh opportunities for rights-holders while adding new layers of complexity to negotiations and deals,” the report says. The full story is on page 7 Screen grab of Discovery’s dedicated campaign site, keepdiscovery.sg CJ E&M ramps up While Singapore crowds spent the week- StarHub is extending bill rebates to edu- Turkish film biz end staring at a giant #keepdiscovery cation and lifestyle customers and is also Korean remakes follow video display on Orchard Road, StarHub offering a free preview of 30 channel to 25 local titles was putting the finishing touches to its 15 July. brand new seven-channel pack includ- StarHub’s decision not to cave to Dis- ing, perhaps ironically, the three-year-old covery’s rumoured US$11-million demands Korea’s CJ E&M is ramping up its Turkish CuriosityStream HD channel launched by raised questions over what rival platform operations, adding 25 local titles to its Discovery founder John Hendricks. -

The Digital First Journey

The ‘Digital First’ journey How OTT platforms can remain ‘on-demand ready’ October 2017 KPMG.com/in © 2016 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. Disclaimers: • All product names, logos, trademarks, service marks and brands are property of their respective owners • The information contained in this report is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. No one should act on such information without appropriate professional advice after a thorough examination of the particular situation. • Although we have attempted to provide correct and timely information, there can be no guarantee that such information is correct as of the date it is received or that it will continue to be correct in the future. • The report contains information obtained from the public domain or external sources which have not been verified for authenticity, accuracy or completeness. • Use of companies’ names in the report is only to exemplify the trends in the industry. We maintain our independence from such entities and no bias is intended towards any of them in the report. • Our report may make reference to ‘KPMG in India’s analysis’; this merely indicates that we have (where specified) undertaken certain analytical activities on the underlying data to arrive at the information presented; we do not accept responsibility for the veracity of the underlying data. • In connection with the report or any part thereof, KPMG in India does not owe duty of care (whether in contract or in tort or under statute or otherwise) to any person / party to whom / which the report is circulated to and KPMG in India shall not be liable to any such person / party who / which uses or relies on this report. -

KPMG FICCI 2013, 2014 and 2015 – TV 16

#shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 kpmg.com/in ficci-frames.com We would like to thank all those who have contributed and shared their valuable domain insights in helping us put this report together. Images Courtesy: 9X Media Pvt.Ltd. Phoebus Media Accel Animation Studios Prime Focus Ltd. Adlabs Imagica Redchillies VFX Anibrain Reliance Mediaworks Ltd. Baweja Movies Shemaroo Bhasinsoft Shobiz Experential Communications Pvt.Ltd. Disney India Showcraft Productions DQ Limited Star India Pvt. Ltd. Eros International Plc. Teamwork-Arts Fox Star Studios Technicolour India Graphiti Multimedia Pvt.Ltd. Turner International India Ltd. Greengold Animation Pvt.Ltd UTV Motion Pictures KidZania Viacom 18 Media Pvt.Ltd. Madmax Wonderla Holidays Maya Digital Studios Yash Raj Films Multiscreen Media Pvt.Ltd. Zee Entertainmnet Enterprises Ltd. National Film Development Corporation of India with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars: FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 Foreword Making India the global entertainment superpower 2014 has been a turning point for the media and entertainment industry in India in many ways. -

Commonly Used Business and Economic Abbreviations

COMMONLY USED BUSINESS AND ECONOMIC ABBREVIATIONS AAGR Average Annual Growth Rate AAR Average Annual Return ABB Asean Braun Boveri ADAG Anil Dhirubhai Ambani Group ADB Asian Development Bank ADR American Depository Receipts AGM Annual General Meeting APEC Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation APM Administered Price Mechanism ASCII American Standard Code for Information Interchange ASSOCHAM Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry B2B Business to Business B2C Business to Consumer BIS Bank for International Settlements, Bureau of Indian Standards BOP Balance of Payment BPO Business Process Outsourcing BRIC Brazil India Russia China BSE Bombay Stock Exchange CAGR Compounded Annual Growth Rate CEO Chief Executive Officer CFO Chief Financial Officer CII Confederation of Indian Industries CIS Commonwealth of Independent States CMIE Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy CPI Consumer Price Index CRISIL Credit Rating Information Services of India Ltd. CRR Cash Reserve Ratio CSO Central Static’s organization DIAL Delhi International Airport Ltd. EMI Equated Monthly Installment EPS Earnings Per Share EPZ Export Processing Zone ESOP Employee Stock Ownership Plan EXIM Bank Export and Import Bank FDI Foreign Direct Investment FEMA Foreign Exchange Management Act FERA Foreign Exchange Regulation Act FICCI Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry FII Foreign Institutional Investor FIPB Foreign Investment Promotion Board GATT General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade GDP Gross Domestic Product GDR Global Depository Receipt GNP Gross National -

“Conclave on Entrepreneurship” 19Th September, 2014, 9.00Am to 05.30 Pm Hotel Ashoka, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi

“CONCLAVE ON ENTREPRENEURSHIP” 19TH SEPTEMBER, 2014, 9.00AM TO 05.30 PM HOTEL ASHOKA, CHANAKYAPURI, NEW DELHI PROGRAMME DETAILS Session Time Topic 9.00 – 10.00 AM BREAKFAST AND REGISTRATION INAUGURAL PROGRAMME Registration 10.00 – 10.30 AM and Inaugural Welcome and Program objectives – Prof S S Mantha, Chairman, Function AICTE Opening remarks by Guest of Honour – Shri Ashok Thakur, Secretary, Higher Education Department , MHRD Address by Chief Guest – Smt Smriti Zubin Irani – Hon’ble Union Minister for Human Resource Development, Govt of India I 10.30 – 11.30AM Session I: Government Policies, programs, subsidies and opportunities in different sectors. Mr Sunil Arora – Secretary, Skill & Entrepreneurship development Ministry, Govt of India Mr Thomas – CEO & Managing Director, Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor Development Corporation Limited Padma Shri Priam Singh – Director General, IMI , New Delhi Mr Ajay Kumar – Joint Secretary, Ministry of Information Technology, Govt. of India 11.30 – 11.45 AM - Tea break II 11.45- 12.45 PM Session II: Entrepreneurship education, training and Innovation – The speakers include Mr Manish Sabharwal – CEO, Teamlease Mr Ajay Chowdhry – Founder HCL India and Chairman, Board of Governors, IIT Patna. Mr Dilip Cherian – Founder and Consulting Partner, Perfect Relations, 12.45 – 01.30 PM Panel Discussions and Q/A session: The Panelists include Prof. Akshai Agarwal – Vice Chancellor, Gujarat Technical University, Ahmedabad Mr Rajesh Chharia – President Internet Service Provider Association Of India (ISPAI) Prof Anil Wali – MD, Innovation & Tech. Incubation Centre, IIT Delhi Mr Praveen Prakash - Joint Secretary, MHRD, Govt. of India 01.30 – 02.30PM - LUNCH BREAK III 02.30 – 03.30PM Session III: Entrepreneurial opportunities in other sector – The speakers include Mr Prakash Rane – MD, ABM Knowledgeware Ltd, Mumbai Mr Arunabh Kumar – Founder & CEO, The Viral Fever & TVF Media Labs. -

DEFINATION the Capacity and Willingness to Develop, Organize

DEFINATION The capacity and willingness to develop, organize and manage a business venture along with any of its risks in order to make a profit. The most obvious example of entrepreneurship is the starting of new businesses. In economics, entrepreneurship combined with land, labor, natural resources and capital can produce profit. Entrepreneurial spirit is characterized by innovation and risk-taking, and is an essential part of a nation's ability to succeed in an ever changing and increasingly competitive global marketplace. Differences Between Women and Men Entrepreneurs When men and women start companies, do they approach the process the same way? Are there key differences? And how do those differences affect the success of the business venture? As a woman in the start-up community, I am frequently asked about women entrepreneurs. A popular question is: How are they different from men? There have been many studies of entrepreneurs and start-ups, and I’ve read a number of them. Many of them seem to me to fall short, because the researchers, not being entrepreneurs themselves, lack an in-depth understanding of the entrepreneurial mind. The result is often a lot of statistics that fail to enlighten readers about entrepreneurial behavior and motivation. So what follows are my personal opinions. They are not based on formal research, but on my own observations and interactions with other women entrepreneurs. 1. Women tend to be natural multitaskers, which can be a great advantage in start-ups. While founders typically have one core skill, they also need to be involved in many different aspects of their business.