Informal Land Delivery Processes in Greater Gaborone, Botswana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vital Statistics 2015 1 2

STATISTICS VITAL 2015 2 Fax: 3952201 Private Bag 0024, Gaborone. 3671300 1 Tel: [email protected] E-mail: Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw VITAL STATISTICS REPORT 2015 21 4 194347895 VITAL STATISTICS REPORT 2015 Published by Statistics Botswana Private bag 0024, Gaborone Website: www.statsbots.org.bw E-mail: [email protected] Contact: Crime, Civil and Vital Statistics Unit Tel: (267) 3718148 Fax: (267) 3952201 (267)3935628 August 2017 COPYRIGHT RESERVED Extracts may be published if source Is duly acknowledged 2 VITAL STATISTICS REPORT 2015 Preface This is the fifth issue of the Vital Statistics Report produced by the Crime and Vital Statistics unit of Statistics Botswana. The report is intended to provide a quick reference to some basic population indicators as well as the performance of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) in the country. The report is organized in three parts, i) Births, ii) Marriages and iii) Deaths. Events analysed in the report include all occurrences within the borders of the country irrespective of citienship. The tables and figures in this publication are based on information collected from registrations of births, deaths, and marriages, as registered by the Department of Civil and National Registration (CNR) in 2015. The publication is a result of a collaborative effort between Statistics Botswana and the Department of Civil and National Registration of the Ministry of Nationality, Immigration and Gender Affairs. The collaboration has resulted in continual improvement in the quality of vital event data and the quality of this report. A.N Majelantle Statistician General August 2017 3 VITAL STATISTICS REPORT 2015 3 VITAL STATISTICS REPORT 2015 Table of Contents List of Tables........................................................................................................................................................ -

The Parliamentary Constituency Offices

REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA THE PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY OFFICES Parliament of Botswana P O Box 240 Gaborone Tel: 3616800 Fax: 3913103 Toll Free; 0800 600 927 e - mail: [email protected] www.parliament.gov.bw Introduction Mmathethe-Molapowabojang Mochudi East Mochudi West P O Box 101 Mmathethe P O Box 2397 Mochudi P O Box 201951 Ntshinoge Representative democracy can only function effectively if the Members of Tel: 5400251 Fax: 5400080 Tel: 5749411 Fax: 5749989 Tel: 5777084 Fax: 57777943 Parliament are accessible, responsive and accountable to their constituents. Mogoditshane Molepolole North Molepolole South The mandate of a Constituency Office is to act as an extension of Parliament P/Bag 008 Mogoditshane P O Box 449 Molepolole P O Box 3573 Molepolole at constituency level. They exist to play this very important role of bringing Tel: 3915826 Fax: 3165803 Tel: 5921099 Fax: 5920074 Tel: 3931785 Fax: 3931785 Parliament and Members of Parliament close to the communities they serve. Moshupa-Manyana Nata-Gweta Ngami A constituency office is a Parliamentary office located at the headquarters of P O Box 1105 Moshupa P/Bag 27 Sowa Town P/Bag 2 Sehithwa Tel: 5448140 Fax: 5448139 Tel: 6213756 Fax: 6213240 Tel: 6872105/123 each constituency for use by a Member of Parliament (MP) to carry out his or Fax: 6872106 her Parliamentary work in the constituency. It is a formal and politically neutral Nkange Okavango Palapye place where a Member of Parliament and constituents can meet and discuss P/Bag 3 Tutume P O Box 69 Shakawe P O Box 10582 Palapye developmental issues. Tel: 2987717 Fax: 2987293 Tel: 6875257/230 Tel: 4923475 Fax: 4924231 Fax: 6875258 The offices must be treated strictly as Parliamentary offices and must therefore Ramotswa Sefhare-Ramokgonami Selibe Phikwe East be used for Parliamentary business and not political party business. -

A Heritage and Cultural Tourism Destination

MAKING GABORONE A STOP AND NOT A STOP-OVER: A HERITAGE AND CULTURAL TOURISM DESTINATION by Jane Thato Dewah (Student No: 12339556) A Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MAGISTER HEREDITATIS CULTURAEQUE SCIENTIAE (HERITAGE AND CULTURAL STUDIES) (TOURISM) In the Department of Historical and Heritage Studies at the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria SUPERVISOR: Prof. K.L Harris December 2014 DECLARATION OF AUTHENTICITY I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and has not been submitted previously at any other university for a degree. ............................................... Signature Jane Thato Dewah ................................................ Date ii Abstract The main objective of the study was to identify cultural heritage sites in and around Gaborone which could serve as tourist attractions. Gaborone, the capital city of Botswana, has been neglected in terms of tourism, although it has all the facilities needed to cater for this market. Very little information with regards to tourist attractions around Gaborone is available and therefore this study set out to identify relevant sites and discussed their history, relevance and potential for tourism. It also considers ways in which these sites can be developed in order to attract tourists. Due to its exclusive concentration on wildlife and the wilderness, tourism in Botswana tends to benefit only a few. Moreover, it is mainly concentrated in the north western region of the country, leaving out other parts of the country in terms of the tourism industry. To achieve the main objective of the study, which is to identify sites around the capital city Gaborone and to evaluate if indeed the sites have got the potential to become tourist attractions, three models have been used. -

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization. Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ijagbemi, Bayo, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 17:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196133 LAND TENURE REFORMS AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN BOTSWANA: IMPLICATIONS FOR URBANIZATION by Bayo Ijagbemi ____________________ Copyright © Bayo Ijagbemi 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Bayo Ijagbemi entitled “Land Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Thomas Park _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Stephen Lansing _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr David Killick _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Mamadou Baro Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

The Raid on Gaborone, June 14, 1985: a Memorial

The Raid on Gaborone, June 14, 1985: A memorial http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.BOTHISP104 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Raid on Gaborone, June 14, 1985: A memorial Author/Creator Nyelele, Libero; Drake, Ellen Publisher Libero Nyelele and Ellen Drake Date 1985-14-06 Resource type Pamphlets Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Botswana Coverage (temporal) 1985-1986 Source Northwestern University Libraries, 968.1103.N994r Description Table of Contents: The Raid; The Victims: the Dead; The Injured; Property Damage; Epilogue; Poem: Explosion of Fire; Lithograph: the Day After; Post Script Format extent 40 (length/size) http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.BOTHISP104 http://www.aluka.org 6g 6g M, I THE RA ON GABORONE: JUNE 14 l.985 by Libero Nyelele and Ellen Drake n 0**. -

Directory of Financial Institutions Operating in Botswana As at December 31, 2019

PAPER 4 BANK OF BOTSWANA DIRECTORY OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS OPERATING IN BOTSWANA AS AT DECEMBER 31, 2019 PREPARED AND DISTRIBUTED BY THE BANKING SUPERVISION DEPARTMENT BANK OF BOTSWANA Foreword This directory is compiled and distributed by the Banking Supervision Department of the Bank of Botswana. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this directory, such information is subject to frequent revision, and thus the Bank accepts no responsibility for the continuing accuracy of the information. Interested parties are advised to contact the respective financial institutions directly for any information they require. This directory excludes collective investment undertakings and International Financial Services Centre non-bank entities, whose regulation and supervision falls within the purview of the Non-Bank Financial Institutions Regulatory Authority. Lesedi S Senatla DIRECTOR BANKING SUPERVISION DEPARTMENT 2 DIRECTORY OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS OPERATING IN BOTSWANA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. CENTRAL BANK ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2. COMMERCIAL BANKS ........................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 ABSA BANK BOTSWANA LIMITED ........................................................................................................... 7 2.2 AFRICAN BANKING CORPORATION OF BOTSWANA LIMITED .................................................................. -

The Big Governance Issues in Botswana

MARCH 2021 THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE AFRICAN PEER REVIEW MECHANISM Contents Executive Summary 3 Acknowledgments 7 Acronyms and Abbreviations 8 What is the APRM? 10 The BAPS Process 12 Ibrahim Index of African Governance Botswana: 2020 IIAG Scores, Ranks & Trends 120 CHAPTER 1 15 Introduction CHAPTER 2 16 Human Rights CHAPTER 3 27 Separation of Powers CHAPTER 4 35 Public Service and Decentralisation CHAPTER 5 43 Citizen Participation and Economic Inclusion CHAPTER 6 51 Transparency and Accountability CHAPTER 7 61 Vulnerable Groups CHAPTER 8 70 Education CHAPTER 9 80 Sustainable Development and Natural Resource Management, Access to Land and Infrastructure CHAPTER 10 91 Food Security CHAPTER 11 98 Crime and Security CHAPTER 12 108 Foreign Policy CHAPTER 13 113 Research and Development THE BIG GOVERNANCE ISSUES IN BOTSWANA: A CIVIL SOCIETY SUBMISSION TO THE APRM 3 Executive Summary Botswana’s civil society APRM Working Group has identified 12 governance issues to be included in this submission: 1 Human Rights The implementation of domestic and international legislation has meant that basic human rights are well protected in Botswana. However, these rights are not enjoyed equally by all. Areas of concern include violence against women and children; discrimination against indigenous peoples; child labour; over reliance on and abuses by the mining sector; respect for diversity and culture; effectiveness of social protection programmes; and access to quality healthcare services. It is recommended that government develop a comprehensive national action plan on human rights that applies to both state and business. 2 Separation of Powers Political and personal interests have made separation between Botswana’s three arms of government difficult. -

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief For further details contact Census Office, Private Bag 0024 Gaborone: Tel 3188500; Fax 3188610 1. Botswana Population at 2 Million Botswana’s population has reached the 2 million mark. Preliminary results show that there were 2 038 228 persons enumerated in Botswana during the 2011 Population and Housing Census, compared with 1 680 863 enumerated in 2001. Suffice to note that this is the de-facto population – persons enumerated where they were found during enumeration. 2. General Comments on the Results 2.1 Population Growth The annual population growth rate 1 between 2001 and 2011 is 1.9 percent. This gives further evidence to the effect that Botswana’s population continues to increase at diminishing growth rates. Suffice to note that inter-census annual population growth rates for decennial censuses held from 1971 to 2001 were 4.6, 3.5 and 2.4 percent respectively. A close analysis of the results shows that it has taken 28 years for Botswana’s population to increase by one million. At the current rate and furthermore, with the current conditions 2 prevailing, it would take 23 years for the population to increase by another million - to reach 3 million. Marked differences are visible in district population annual growths, with estimated zero 3 growth for Selebi-Phikwe and Lobatse and a rate of over 4 percent per annum for South East District. Most district growth rates hover around 2 percent per annum. High growth rates in Kweneng and South East Districts have been observed, due largely to very high growth rates of villages within the proximity of Gaborone. -

The Politics of Cultural Conservatism in Colonial Botswana: Queen Seingwaeng's Zionist Campaign in the Bakgatla Reserve, 1937-1947

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies, vo1.12, nos.1 & 2 (1998) The politics of cultural conservatism in colonial Botswana: Queen Seingwaeng's Zionist campaign in the Bakgatla Reserve, 1937-1947 Fred Morton Loras College, Iowa, & University of Pretoria Abstract Studies of Christian Zionist churches in southern Africa have suggested that they were non-political. This paper puts the growth of Zionism among the BaKgatla in the context of local political struggles and the life of Queen Seingwaeng, mother of Chief Molefi. She was politically important from the 1910s until the 1960s, articulating the views of ordinary people otherwise considered politically helpless. She led popular opposition to the ''progressive'' authoritarianism of Regent 1sang, promoting the restoration of her son Molefi to chieftainship through religious movements in the 1930s-andjoining the Zion Christian Church in 1938. However, by 1947, Seingwaeng and the Zionists were seen as a political threat by Molefi and the ruling elite, who expelled them from BaKgatla territory. Molefi was reconciled with his mother in 1955, but she did not return home to Mochudi until 1967, nine years after his death. In 1947, Queen Mother Seingwaeng was beaten in public by her son Molefi, kgosi (king) of the BaKgatla, for refusing to abandon the Zion Christian Church (ZCC). -

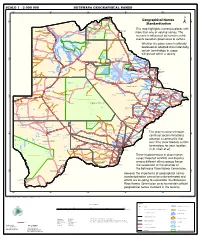

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe -

New List of Archaeologists 2019.Pdf

P Department of National Museum Monument and Art Gallery 331 Independence Avenue Gaborone, Botswana Private Bag 00114 Tel: (267) 3974616 (267) 3610400 Fax: (267) 3902797 Email: [email protected] Website: www.national- museum.gov.bw A LIST OF APPROVED ARCHAEOLOGISTS 2019 Our reference Dr Alfred Tsheboeng Dr Alinah Segobye P.O. Box 2789 University of Botswana Gaborone International Finance Park P/Bag 0022, Gaborone Plot 128,Kgale Court, Unit 8, Gaborone Tel: 3162036 Cel: 71374291 Tel: 3552281 Cel: 71625018 e-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Catrien Van Waarden Dr Nick Walker Marope Research Achilles Investments Pty Ltd P.O. Box 910, Francistown Gaborone Tel: 2414257 Cell: 71378415 Email: [email protected] [email protected] P. Sekgarametso-Modikwa Pena Monageng Archaeological Resources Management Services Ditso Archaeological Surveys P.O. Box 601271 P/Bag 0029, suit no 285 Gaborone Postnet Mogoditshane Tel: 3922289 cell: 71653378 Tel: 3552267 Cell: 71728860 Fax: 3922289 Fax: 3938757 Email: [email protected] Mr. O.J. NOKO Mr. Donald Mookodi Crystal Touch (Pty) Ltd Geoarch Investment Pty Ltd Postnet Kgale View P.O. Box 10111 P/Bag 351 suite 418 Gaborone Gaborone, Botswana Tel: (5442552 Cell: 71710397 Cell: 72202884 Fax: 3975566 Email: [email protected]/ 1 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Mr. Oscar Motsumi Nyatsego L. Baeletsi Watershed (Pty) Ltd Kgato-Go-Ya-Pele (Pty) Ltd P.O. Box 3347 P.O. Box 202850 Gaborone, Botswana Gaborone Tel: (09267) 316400/3699840 Tel/Fax: 3185133 Cel: 71676356 Cel: (09267) 71313089/74222285 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] motsumio@botsnet-bw Dr Susan O. -

Tuesday 02 February 2021 the Second Meeting of The

THE SECOND MEETING OF THE SECOND SESSION OF THE TWELFTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY 02 FEBRUARY 2021 ENGLISH VERSION HANSARD NO: 201 THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SPEAKER The Hon. Phandu T. C. Skelemani PH, MP. DEPUTY SPEAKER The Hon. Mabuse M. Pule, MP. (Mochudi East) Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms B. N. Dithapo Deputy Clerk of the National Assembly - Mr L. T. Gaolaolwe Learned Parliamentary Counsel - Ms M. Mokgosi Assistant Clerk (E) - Mr R. Josiah CABINET His Excellency Dr M. E. K. Masisi, MP. - President His Honour S. Tsogwane, MP. (Boteti West) - Vice President Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Hon. K. N. S. Morwaeng, MP. (Molepolole South) - Administration Hon. K. T. Mmusi, MP. (Gabane-Mmankgodi) - Minister of Defence, Justice and Security Hon. Dr L. Kwape, MP. (Kanye South) - Minister of International Affairs and Cooperation Hon. E. M. Molale, MP. (Goodhope-Mabule ) - Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Hon. K. S. Gare, MP. (Moshupa-Manyana) - Minister of Agricultural Development and Food Security Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation Hon. P. K. Kereng, MP. (Specially Elected) - and Tourism Hon. Dr E. G. Dikoloti MP. (Mmathethe-Molapowabojang) - Minister of Health and Wellness Hon. T.M. Segokgo, MP. (Tlokweng) - Minister of Transport and Communications Hon. K. Mzwinila, MP. (Specially Elected) - Minister of Land Management, Water and Sanitation Services Minister of Youth Empowerment, Sport and Culture Hon. T. M. Rakgare, MP. (Mogoditshane) - Development Hon. A. M. Mokgethi, MP. (Gaborone Bonnington North) - Minister of Nationality, Immigration and Gender Affairs Hon. Dr T. Matsheka, MP. (Lobatse) - Minister of Finance and Economic Development Hon. F. M. M.