Institutional Framework for the Management of Peri- Urban Areas in Kenya: the Case of Ongata Rongai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology of the Nairobi Region, Kenya

% % % % % % % % %% %% %% %% %% %% %% % GEOLOGIC HISTORY % %% %% % % Legend %% %% %% %% %% %% %% % % % % % % HOLOCENE: %% % Pl-mv Pka %%% Sediments Mt Margaret U. Kerichwa Tuffs % % % % %% %% % Longonot (0.2 - 400 ka): trachyte stratovolcano and associated deposits. Materials exposed in this map % %% %% %% %% %% %% % section are comprised of the Longonot Ash Member (3.3 ka) and Lower Trachyte (5.6-3.3 ka). The % Pka' % % % % % % L. Kerichwa Tuff % % % % % % Alluvial fan Pleistocene: Calabrian % % % % % % % Geo% lo% gy of the Nairobi Region, Kenya % trachyte lavas were related to cone building, and the airfall tuffs were produced by summit crater formation % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Pna % % % % %% % (Clarke et al. 1990). % % % % % % Pl-tb % % Narok Agglomerate % % % % % Kedong Lake Sediments Tepesi Basalt % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % %% % % % 37.0 °E % % % % 36.5 °E % % % % For area to North see: Geology of the Kijabe Area, KGS Report 67 %% % % % Pnt %% % PLEISTOCENE: % % %% % % % Pl-kl %% % % Nairobi Trachyte % %% % -1.0 ° % % % % -1.0 ° Lacustrine Sediments % % % % % % % % Pleistocene: Gelasian % % % % % Kedong Valley Tuff (20-40 ka): trachytic ignimbrites and associated fall deposits created by caldera % 0 % 1800 % % ? % % % 0 0 % % % 0 % % % % % 0 % 0 8 % % % % % 4 % 4 Pkt % formation at Longonot. There are at least 5 ignimbrite units, each with a red-brown weathered top. In 1 % % % % 2 % 2 % % Kiambu Trachyte % Pl-lv % % % % % % % % % % %% % % Limuru Pantellerite % % % % some regions the pyroclastic glass and pumice has been -

Kenya, Groundwater Governance Case Study

WaterWater Papers Papers Public Disclosure Authorized June 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized KENYA GROUNDWATER GOVERNANCE CASE STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized Albert Mumma, Michael Lane, Edward Kairu, Albert Tuinhof, and Rafik Hirji Public Disclosure Authorized Water Papers are published by the Water Unit, Transport, Water and ICT Department, Sustainable Development Vice Presidency. Water Papers are available on-line at www.worldbank.org/water. Comments should be e-mailed to the authors. Kenya, Groundwater Governance case study TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................................. vi ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................ viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................................ xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... xiv 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. GROUNDWATER: A COMMON RESOURCE POOL ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2. CASE STUDY BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. -

Appendix 11 Future Socio-Economic Framework

APPENDIX 11 FUTURE SOCIO-ECONOMIC FRAMEWORK Page 11.1 DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL AND CONSTRAINT A11-1 11.2 URBAN LAND USE TYPES AND DISTRIBUTING PRINCIPLES A11-4 NUTRANS The Study on Master Plan for Urban Transport in the Nairobi Metropolitan Area APPENDIX 11 FUTURE SOCIO-ECONOMIC FRAMEWORK 11.1 DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL AND CONSTRAINT Water Supply Capacity The existing water supply in the Nairobi City has four sources, namely Kikuyu Spring, Sasumua Dam, Ruiru Dam, and Ngethu. Water shortage is a growing problem in the Nairobi Metropolitan Area because of the water loss reportedly amounting to some 50% of total water supply and expanding population. Water supply plan with target year 2000 was formulated in the “Third Nairobi Water Supply Project". The projected population of Nairobi City would be 3.86 million and corresponding projected water demand would be 752.2 thousand cubic meters per day in 2010. Planned area of piped water supply covers the whole Nairobi City and some part of Ruiru to the north, and Syokimau to the southeast. Local area water supply projects are proposed in Ngong and Ongata Rongai to the southwest and Western Shamba Area to the northwest of Nairobi City. Gravity type water supply system can be applicable to the areas less than 1,700m above sea level in the Nairobi Metropolitan Region (See Figure 11.1-1). FIGURE 11.1-1 WATER SUPPLY SCHEME IN NAIROBI CITY Final Report Appendix A11-1 NUTRANS The Study on Master Plan for Urban Transport in the Nairobi Metropolitan Area Sewerage Treatment Plan The whole Nairobi City is not covered by the existing sewerage system managed by Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company. -

Registered Voters Per Caw for 2017 General Elections

REGISTERED VOTERS PER CAW FOR 2017 GENERAL ELECTIONS NO. OF COUNTY CONST_ CAW_ COUNTY_NAME CONSTITUENCY_NAME CAW_NAME VOTERS POLLING _CODE CODE CODE STATIONS 001 MOMBASA 001 CHANGAMWE 0001 PORT REITZ 17,082 26 001 MOMBASA 001 CHANGAMWE 0002 KIPEVU 13,608 22 001 MOMBASA 001 CHANGAMWE 0003 AIRPORT 16,606 26 001 MOMBASA 001 CHANGAMWE 0004 CHANGAMWE 17,586 29 001 MOMBASA 001 CHANGAMWE 0005 CHAANI 21,449 33 001 MOMBASA 002 JOMVU 0006 JOMVU KUU 22,269 36 001 MOMBASA 002 JOMVU 0007 MIRITINI 16,899 27 001 MOMBASA 002 JOMVU 0008 MIKINDANI 30,139 46 001 MOMBASA 003 KISAUNI 0009 MJAMBERE 22,384 34 001 MOMBASA 003 KISAUNI 0010 JUNDA 23,979 37 001 MOMBASA 003 KISAUNI 0011 BAMBURI 17,685 28 001 MOMBASA 003 KISAUNI 0012 MWAKIRUNGE 4,946 9 001 MOMBASA 003 KISAUNI 0013 MTOPANGA 17,539 28 001 MOMBASA 003 KISAUNI 0014 MAGOGONI 14,846 23 001 MOMBASA 003 KISAUNI 0015 SHANZU 24,772 39 001 MOMBASA 004 NYALI 0016 FRERE TOWN 20,215 33 001 MOMBASA 004 NYALI 0017 ZIWA LA NG'OMBE 20,747 31 001 MOMBASA 004 NYALI 0018 MKOMANI 19,669 31 001 MOMBASA 004 NYALI 0019 KONGOWEA 24,457 38 001 MOMBASA 004 NYALI 0020 KADZANDANI 18,929 32 001 MOMBASA 005 LIKONI 0021 MTONGWE 13,149 23 001 MOMBASA 005 LIKONI 0022 SHIKA ADABU 13,089 21 001 MOMBASA 005 LIKONI 0023 BOFU 18,060 28 001 MOMBASA 005 LIKONI 0024 LIKONI 10,855 17 001 MOMBASA 005 LIKONI 0025 TIMBWANI 32,173 51 001 MOMBASA 006 MVITA 0026 MJI WA KALE/MAKADARA 19,927 34 001 MOMBASA 006 MVITA 0027 TUDOR 20,380 35 001 MOMBASA 006 MVITA 0028 TONONOKA 21,055 36 001 MOMBASA 006 MVITA 0029 SHIMANZI/GANJONI 17,312 33 001 MOMBASA -

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 Bank: 01 Kenya Commercial Bank Limited (Clearing centre: 01) Branch code Branch name 091 Eastleigh 092 KCB CPC 094 Head Office 095 Wote 096 Head Office Finance 100 Moi Avenue Nairobi 101 Kipande House 102 Treasury Sq Mombasa 103 Nakuru 104 Kicc 105 Kisumu 106 Kericho 107 Tom Mboya 108 Thika 109 Eldoret 110 Kakamega 111 Kilindini Mombasa 112 Nyeri 113 Industrial Area Nairobi 114 River Road 115 Muranga 116 Embu 117 Kangema 119 Kiambu 120 Karatina 121 Siaya 122 Nyahururu 123 Meru 124 Mumias 125 Nanyuki 127 Moyale 129 Kikuyu 130 Tala 131 Kajiado 133 KCB Custody services 134 Matuu 135 Kitui 136 Mvita 137 Jogoo Rd Nairobi 139 Card Centre Page 1 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 140 Marsabit 141 Sarit Centre 142 Loitokitok 143 Nandi Hills 144 Lodwar 145 Un Gigiri 146 Hola 147 Ruiru 148 Mwingi 149 Kitale 150 Mandera 151 Kapenguria 152 Kabarnet 153 Wajir 154 Maralal 155 Limuru 157 Ukunda 158 Iten 159 Gilgil 161 Ongata Rongai 162 Kitengela 163 Eldama Ravine 164 Kibwezi 166 Kapsabet 167 University Way 168 KCB Eldoret West 169 Garissa 173 Lamu 174 Kilifi 175 Milimani 176 Nyamira 177 Mukuruweini 180 Village Market 181 Bomet 183 Mbale 184 Narok 185 Othaya 186 Voi 188 Webuye 189 Sotik 190 Naivasha 191 Kisii 192 Migori 193 Githunguri Page 2 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 194 Machakos 195 Kerugoya 196 Chuka 197 Bungoma 198 Wundanyi 199 Malindi 201 Capital Hill 202 Karen 203 Lokichogio 204 Gateway Msa Road 205 Buruburu 206 Chogoria 207 Kangare 208 Kianyaga 209 Nkubu 210 -

Kajiado Base

KAJIADO BASE MAP 14 October 2009 MARAGUA Sudan CENTRAL MWINGI KAMWANGI KANDARA NDITHINI Ethiopia GATANGA NAIVASHA MASINGA LARI Eastern GATUNDU KAKUZI Rift valley MIGWANI Uganda Somalia GITHUNGURI THIKA MUNICIPALITY Western N. Eastern p Central MAU LIMURU Nyanza RUIRU Nairobi Ewasop KIAMBAA (! Coast p YATTA KABATI KIKUYU MATUNGULU Tanzania NORTH KEEKONYOKIE Kerarapon (! (! MAKADARA p KANGUNDO MWALA Ewaso Nkidong (!p(!(! (! p p (! (! MAVOKO Emerit KISERIAN NGONGp Ongata Rongai KATHIANI Oldorko (! p(! (!p p p ONGATA NGONG Njoroi (!Olepolos p YATHUI (! (! p KITENKELA CENTRAL KITUI CENTRAL KEEKONYOKIE p(! Ol Orian Kitengela OSUPUKO pOltepesi Olooloitikosh(! (! (! Stony Athi CENTRAL MACHAKOS Esonorua (! CHULUNI (! SOUTH KEEKONYOKIE Shanamu OLTUROTOp KISAU (! Isinya KALAMA Embalbal (! MBOONI KALAWA p (! p Oloiyiangalan p ISINYA MAGADI(! (! OLKIRAMATIAN p (!Enkirigirri KAITI p KILUNGU Nguruman WOTE (! OLDONYO NYOIKE TOWNSHIP ILDAMAT pp ILMUNKUSH KILOME LOITA (!Olkeramationp Elangata Wuas SAJILONIp(! Kiu p p (! p p (! MATILIKU (! Karero Kalebwani KATHONZWENI LOODOKILANI (! Kima MAGADI p ENKORIKA(! (! p CENTRAL KAJIADO NKOILE p Sultan Hamud SHOMPOLE OLOBELIBEL IMARORO ARROI (!MBITINI p ENKARONI OLOONTULUGUM(! Emali NGUU Ilbisil p MASHURU (! (!Shombole (! Mashuru (!p Longuswa p p NKAMA (! Mashuru (! Simba LOROGOSWA p OSILALEI Kibini (! p (! Selengei p p POKA KENYEWA p TOROSEIp Oloiseri BISSIL (!MAPARASHA (! p Ngatataek MAKINDU p(! Emotoroki p p(! Olosingaram NAMANGA MURUESHI p (! (! METO Mailua LENKISM Merueshi p (! KIBWEZI Meto Ngabole p(!Lengesim (! (! MAILWA NAMANGA Olkulului CHULU GAME RES p Makutano (! (! ENTONET IMBIRIKANI p p p (! Olngoswa (! Ol Tukai LOITOKITOK p KIMANA Kimana p (! KUKU Enkutoto (! Iltilal (! KENYA DISTRICT MAP p Oloitokitok (! (! (!Ekuku Airfields (!pp p (!Ilasit p p Hospitals p Rombo (! Major Towns p(! ROMBO Map Doc Name: KE_Kajiado base Map Creation Date: 15 Oct 2009 Major rivers Projection/Datum: WGS 1984 Web Resources: http://ochaonline.un.org/kenya Major roads Nominal Scale at A4 paper size: 1:2,000,000 05 10 20 30 Kms Lakes TSAVO N. -

Land Price Index

The Hass Property INDEX Q2.15 LAND INDEX IN ASSOCIATION WITH Expanded land index shows property in satellite towns has had higher return on investment • Hass and Stanlib today unveil the extended Land Index, covering satellite towns in the Nairobi environs. • The new data shows strong development and investment in these areas with land price growth equaling and bettering those in the inner city suburbs. • Since 2007, land in the inner city suburbs have increased five fold, while land prices in the satellite towns have increased six fold. • Over the past 7 years, Athi River and Juja have posted the best returns, while Kiambu has shown the strongest growth over the 12 months and Kiserian in the quarter ended June 2015. • A high interest rate environment further exacerbated by the recent increase of the central bank rate may drive demand for inner city land as developers move to areas with cash driven purchases. Land Index Highlights: The Hass Composite Land Index, Nairobi Suburbs Quarter % Change Annual % Change Change From 2007 Nairobi-18 Index Results 1.6% 13.6% 5.59 Fold Suburb with Highest Quarterly Increase in Land Price Donholm ( +5.1% over last quarter) Suburb with Highest Annual Increase in Land Price Loresho ( +31.5% over last year) Suburb with Lowest Quarterly Increase in Land Price Eastleigh ( -5.8% over last quarter) Suburb with Lowest Annual Increase in Land Price Eastleigh ( -5.0% over last year) The Hass Composite Land Index, Nairobi Satellite Towns Quarter % Change Annual % Change Change From 2007 Nairobi Satellite-14 Index Results 1.9% 8.3% 6.17 Fold Suburb with Highest Quarterly Increase in Land Price Kiserian ( +5.4% over last quarter) Suburb with Highest Annual Increase in Land Price Kiambu ( +21.5% over last year) Suburb with Lowest Quarterly Increase in Land Price Ongata Rongai ( -1.2% over last quarter) Suburb with Lowest Quarterly Increase in Land Price Ongata Rongai ( -0.4% over last year) HassConsult Limited | ABC Place, Waiyaki Way | P.O. -

Kajiado District Environment Action Plan 2009-2013 Executive Summary

REPUBLIC OF KENYA MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND MINERAL RESOURCES i KAJIADO DISTRICT ENVIRONMENT ACTION PLAN 2009-2013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Economic growth and environment are closely intertwined in Kenya. Environmental Action Planning is a tool that aims at enhancing the integration of environment into development planning. Kajiado District is not an exception and has to contend with these challenges with some being unique to the District. The DEAP covers three districts curved out and includes, Kajiado North, Kajiado Central and Kjiado South Districts of the Challenges experienced in the Districts include poverty that has led to the over-use and destruction of environment. Continued reliance on trees for fuel has led to deforestation. Annual flooding continues to destroy lives, property and frustrate livelihood activities. The DEAP highlights priority themes and activities for the District towards achieving sustainable development. The report is divided into 8 Chapters. Chapter one gives the challenges of sustainable development and also describes the rationale for and preparatory process of the DEAP and presents the district’s main profile covering the physical features, demographic, agro- ecological zones, and main environmental issues. Chapter two describes the District’s Environment and Natural resources of Land, Water, Biodiversity (forest, wildlife, and Dry lands biodiversity), and agriculture, livestock and fisheries, land, biodiversity loss and land tenure. For each resource, major environmental issues, challenges and proposed interventions are identified. Chapter three details the human settlements and infrastructure in Kajiado District covering situation analysis, challenges and proposed interventions. Environmental challenges addressed include; waste management, sanitation, pollution, diseases, land use, demand for water, energy, materials for construction. -

Kenya Urban Biomass Fuel Supplier Profile

DfID-KaR Fuel Substitution – Poverty Impacts on Biomass Fuel Suppliers Kenya Urban Biomass Fuel Supplier Profile Draft Report 1.0 Brief Description of Nairobi urban areas Nairobi is linked to the rest of the country by six main roads. These are Mombasa Road which links the city to the coastal and southern regions; Thika Road that links it to the Mount Kenya region, and Naivasha road that links it to the Northwestern Rift Valley regions. Other main roads include Ngong and Ongata Rongai, Kiambu, Gigiri and Kangundo Road. These roads are important as they are conduit for supplying charcoal and other fuel-wood to Nairobi residents from up-country. Nairobi boasts of the Nairobi National Park to the southwest, Ngong forest to the South-east and Karura forest to the North-east. These forests are a great source of wood-fuel chiefly firewood to the lower income people and slum residents. The city is 1.5 o South of the Equator and hence basks in all the sun of a tropical city. Its altitude of 5,000 to 6,000 feet means that the climate is temperate. Rainfall is roughly divided between two rainy seasons: the short rains fall in November and early December, and the long rains between April and mid-June. Because it is virtually on the equator Nairobi has a constant twelve hours of daylight per day all year round. It covers about 700 (696.1) square kilometres including the 120 square kilometres of the Nairobi Game Park and all of Jomo Kenyatta International Airport. The population of Nairobi is estimated to be more than 2.5 million as per 1999 and the number of households slightly more than 800,000. -

World Bank Document

84702 Nairobi Metropolitan Services Improvement Project (NaMSIP) Summary Procurement Plan I. General Public Disclosure Authorized The following procurement plan has been developed for project implementation during the period February 2014 to January 2015 and provides the basis for the procurement methods and Bank prior/post review thresholds. The plan will be updated when need arises to reflect the actual project implementation needs. 1. Project information: Country / Borrower: Republic of Kenya Project: Nairobi Metropolitan Services Improvement Project (NaMSIP) IDA Credit No. 51020-KE Public Disclosure Authorized Project Implementing Agencies: Ministry of Nairobi Metropolitan Development (MoNMED). 2. Bank’s approval Date of the Revised Procurement Plan: February15, 2014 3. Date of General Procurement Notice: 3rd April, 2012 4. Period covered by this procurement plan: February, 2014 - January 2015 II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: Procurement Method (with Prior Review Threshold Comments Threshold in US Dollars for in US Dollars Goods and Works) 1. Goods the first two NCB contracts of any value would also be ICB ≥3,000,000 ≥1,000,000 prior reviewed. NCB <3,000,000 Public Disclosure Authorized 2 Works the first two NCB contract of any value would also be ICB ≥15,000,000 ≥10,000,000 prior reviewed. NCB <15,000,000 3 Direct Contracting All Page 1 of 11 Procurement Method (with Prior Review Threshold Comments Threshold in US Dollars for in US Dollars Goods and Works) Goods/Works Shopping Goods Below 100,000 4 Shopping Works Below 200,000 2. -

Postal Codes20-15

POST CODES FOR ALL POST OFFICES PLEASE INCLUDE THE POST CODES BEFORE SENDING YOUR LETTER NAIROBI CITY OFFICES POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE 00515 BURUBURU 40101 AHERO 20115 EGERTON 2 0157 KABARAK 2 0501 KEEKOROK 9 0111 KIVUNGA 8 0200 MALINDI 9 0128 MTITU ANDEI 4 0632 NYAMONYE 4 0308 SINDO 30101 AINABKOI 90139 EKALAKALA 7 0300 MANDERA 8 0117 MTOPANGA 2 0423 SIONGIROI 00200 CITY SQUARE 3 0400 KABARNET 4 0413 KEHANCHA 3 0305 KOBUJOI 4 0333 NYANDHIWA 00516 DANDORA 40139 AKALA 20102 ELBURGON 3 0401 KABARTONJO 4 0301 KENDU BAY 9 0108 KOLA 6 0101 MANYATTA 8 0109 MTWAPA 4 0126 NYANGANDE 5 0208 SIRISIA 00610 EASTLEIGH 50244 AMAGORO 20103 ELDAMA RAVINE 9 0205 KABATI 0 1020 KENOL 4 0102 KOMBEWA 5 0300 MARAGOLI 5 0423 MUBWAYO 4 0127 NYANGORI 4 0109 SONDU 00521 EMBAKASI 20424 AMALO (FORMERLY 3 0100 ELDORET 2 0114 KABAZI 4 0211 KENYENYA 4 0103 KONDELE 1 0205 MARAGUA 1 0129 MUGUNDA 4 0502 NYANSIONGO 4 0110 SONGHOR 00500 ENTERPRISE ROAD OLOOMIRANI) 7 0301 ELWAK 2 0201 KABIANGA 2 0200 KERICHO 1 0234 KORA 2 0600 MARALAL 4 0107 MUHORONI 4 0514 NYARAMBA 2 0205 SOSIOT 00601 GIGIRI 50403 AMUKURA 9 0121 EMALI 3 0303 KABIYET 2 0131 KERINGET 4 0104 KORU 8 0113 MARIAKANI 4 0409 MUHURU BAY 4 0402 NYATIKE 2 0406 SOTIK 00100 G.P.O NAIROBI 40309 ASUMBI 6 0100 EMBU 3 0601 KACHELIBA 4 0202 KEROKA 4 0332 KOSELE 3 0403 MARIGAT 5 0225 MUKHE 1 0100 NYERI 2 0319 SOUTH-KINANGOP 00101 JAMIA 00204 ATHI RIVER 5 0314 EMUHAYA 4 0223 KADONGO 1 0300 KERUGOYA 5 0117 KOYONZO 6 0408 MARIMA 1 0103 MUKURWEINI 4 0611 NYILIMA 3 0105 SOY 00501 J.K.I.A. -

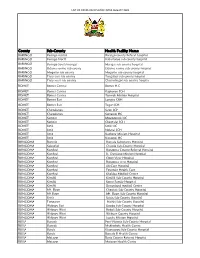

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye