MEASUREMENT of STIBINE and ARSINE GENERATION from the EXIDE 3100-Ah LEAD-ACID MODULE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risto Laitinen/August 4, 2016 International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Division VIII Chemical Nomenclature and Structur

Approved Minutes, Busan 2015 Risto Laitinen/August 4, 2016 International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Division VIII Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Approved Minutes of Division Committee Meeting in Busan, Korea, 8–9 August, 2015 1. Welcome, introductory remarks and housekeeping announcements Karl-Heinz Hellwich (KHH) welcomed everybody to the meeting, extending a special welcome to those who were attending the Division Committee meeting for the first time. He described house rules and arrangements during the meeting. KHH also regretfully reported that it has come to his attention that since the Bangor meeting in August 2014, Prof. Derek Horton (Member, Division VIII task groups on Carbohydrate and Flavonoids nomenclature; Associate Member, IUBMB-IUPAC Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature) and Dr. Libuse Goebels, Member of the former Commission on Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry) have passed away. The meeting attendees paid a tribute to their memory by a moment of silence. 2. Attendance and apologies Present: Karl-Heinz Hellwich (president, KHH) , Risto Laitinen (acting secretary, RSL), Richard Hartshorn (past-president, RMH), Michael Beckett (MAB), Alan Hutton (ATH), Gerry P. Moss (GPM), Michelle Rogers (MMR), Jiří Vohlídal (JV), Andrey Yerin (AY) Observers: Leah McEwen (part time, chair of proposed project, LME), Elisabeth Mansfield (task group chair, EM), Johan Scheers (young observer, day 1; JS), Prof. Kazuyuki Tatsumi (past- president of the union, part of day 2) Apologies: Ture Damhus (secretary, TD), Vefa Ahsen, Kirill Degtyarenko, Gernot Eller, Mohammed Abul Hashem, Phil Hodge (PH), Todd Lowary, József Nagy, Ebbe Nordlander (EN), Amélia Pilar Rauter (APR), Hinnerk Rey (HR), John Todd, Lidija Varga-Defterdarović. -

Toward a List of Molecules As Potential Biosignature Gases for the Search for Life on Exoplanets and Applications to Terrestrial Biochemistry

Toward a List of Molecules as Potential Biosignature Gases for the Search for Life on Exoplanets and Applications to Terrestrial Biochemistry The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Seager, S.; Bains, W. and Petkowski, J.J. “Toward a List of Molecules as Potential Biosignature Gases for the Search for Life on Exoplanets and Applications to Terrestrial Biochemistry.” Astrobiology 16, no. 6 (June 2016): 465–485 ©2016 Mary Ann Liebert, Inc As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/ast.2015.1404 Publisher Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/109943 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. ASTROBIOLOGY Volume 16, Number 6, 2016 ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/ast.2015.1404 Toward a List of Molecules as Potential Biosignature Gases for the Search for Life on Exoplanets and Applications to Terrestrial Biochemistry S. Seager,1,2 W. Bains,1,3 and J.J. Petkowski1 Abstract Thousands of exoplanets are known to orbit nearby stars. Plans for the next generation of space-based and ground-based telescopes are fueling the anticipation that a precious few habitable planets can be identified in the coming decade. Even more highly anticipated is the chance to find signs of life on these habitable planets by way of biosignature gases. But which gases should we search for? Although a few biosignature gases are prominent in Earth’s atmospheric spectrum (O2,CH4,N2O), others have been considered as being produced at or able to accumulate to higher levels on exo-Earths (e.g., dimethyl sulfide and CH3Cl). -

HIGH HAZARD GAS Review Date: 09/23/2019

University of Pittsburgh EH&S Guideline Number: 04-021 Safety Manual Subject: Effective Date: 04/19/2017 Page 1 of 9 HIGH HAZARD GAS Review Date: 09/23/2019 STORAGE AND USE OF HIGH HAZARD GAS 1. Definition of High Hazard (HH) Gases For these guidelines, any gas meeting one or more of the following definitions based on International Fire Code (IFC) and National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standards: 1.1. Flammable gas – a material that is a gas at 68ºF (20ºC) or less at an absolute pressure of 14.7 psi (101.325 kPa) when in a mixture of 13% or less by volume with air, or that has a flammable range at an absolute pressure of 14.7 psi (101.325 kPa) with air of at least 12%, regardless of the lower limit 1.2. Pyrophoric gas – a gas with an autoignition temperature in air at or below 130ºF (54.4ºC) 1.3. Health Hazard 3 (HH3) gas – material that, under emergency conditions and according to the standards, can cause serious or permanent injury 1.4. Health Hazard 4 (HH4) gas – material that, under emergency conditions and according to the standards, can be lethal The storage and usage of a gas or gases meeting any of the above definitions must follow all applicable IFC and NFPA guidelines and the requirements outlined in this document. Consult EH&S for specific guidance on gas mixtures containing corrosive, flammable or poisonous gas components (ex. 1% carbon monoxide/nitrogen, 5% hydrogen sulfide/helium). 2. Notification Requirements Prior to Obtaining High Hazard Gases 2.1. -

Chemical Terrorism Fact Sheet

Chemical Terrorism Fact Sheet Blood Agents - Arsines Arsine has a mild garlic odor. Photo courtesy of the Garlic Information Center, UK (Arsenic Hydride, AsH3) Protective Equipment/Detection Chemical Overview A positive-pressure, self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) or supplied-air First identified in 1775, arsine is a respirator with a full-facepiece, or an air-purifying, full-facepiece respirator (gas highly poisonous, colorless, nonirritat- mask) with a chin-style, front- or back-mounted canister, is recommended for ing, flammable gas with a mild garlic odor at concentrations of 0.5 ppm and protection. Chemical-protective clothing is not required because arsine gas is not above (a level 10-fold greater than absorbed through the skin and does not cause skin irritation. OSHA permissible levels). Two and one half times heavier than air, it will settle to low-lying areas. It is soluble Decontamination in water, and slightly soluble in alcohol and alkalis. Victims exposed only to arsine gas do not need decontamination, but should be re- moved immediately from the contaminated environment. Arsine results when nascent hydrogen is generated in the presence of arsenic, or when water reacts with a metallic arse- nide. Fungi in the presence of arsenic Signs and Symptoms (especially in sewage) can also produce arsine. Stibine (SbH ), a toxic gas that Arsine is the most acutely toxic form of arsenic and preferentially binds to hemoglo- 3 is formed when antimony is exposed to bin. Inhibition of catalase may lead to the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide, which, nascent hydrogen, equals or surpasses as an oxidizer, destroys red cell membranes and aids the arsine-induced conversion of arsine in toxicity and causes a specific +2 +3 Fe to Fe , which further impairs oxygen transport. -

Highly Hazardous Substance

CAPP Table of Substances Alphabetical Order Threshold Two Two Tox(T) Toxic Quantity Release Release or End- Chemical Name Alternate Mixture CAS (lbs) Quantity Source Flam(F) point Chemical Name Description Number (lbs) note 1 (mg/L) Acetaldehyde Ethanal 75-07-0 2,500 1,000 1 F Acetylene Ethyne 74-86-2 10,000 1,000 3 F Acrolein 2-Propenol 107-02-8 150 1 1 & 2 T 0.0011 Acrylonitrile 2-Propenenitrile 107-13-1 20,000 100 1 & 2 T 0.076 Acrylyl chloride 2-Propenoyl 814-68-6 250 100 2 T 0.00090 chloride Alkylaluminums 5,000 50* 3 Allyl alcohol 2-Propen-1-ol 107-18-6 15,000 100 1 & 2 T 0.036 Allyl chloride 3-chloropropene 107-05-1 1,000 100 3 T 0.1252 Allylamine 2-Propen-1-amine 107-11-9 1,000 500 2 T 0.0032 Ammonia Anhydrous Anhydrous 7664-41-7 5,000 100 1 & 2 T 0.14 Ammonia Ammonia Ammonia 20wt% to 44 7664-41-7 20,000 1,000 1 T 0.14 solution wt% note 2 Ammonium hydroxide Ammonia Ammonia concentration 7664-41-7 10,000 1,000 1 T 0.14 solution greater than 44% ammonia note 2 Ammonium by weight hydroxide Ammonium 7790-98-9 7,500 75* 3 perchlorate Ammonium 7787-36-2 7,500 75* 3 permanganate Arsenous trichloride 7784-34-1 15,000 1 1 & 2 T 0.010 Arsine Arsenic Hydride 7784-42-1 100 10 3 T 0.0019 bis(Chloromethyl) Chloromethyl 542-88-1 100 10 1 & 2 T 0.00025 Ether Ether Boron trichloride 10294-34-5 2,500 100 3 T 0.010 Boron trifluoride 7637-07-2 250 25 3 T 0.028 Nevada Administrative Code - Chapter 459 - NAC 459.952 - 459.95528 – Unofficial Revision Effective February 15, 2005 page 1 Threshold Two Two Tox(T) Toxic Quantity Release Release or End- Chemical -

64 1 PAPERS READ BEFORE the CHEMICAL SOCIETY. by FRANCIS

View Article Online / Journal Homepage / Table of Contents for this issue 64 1 PAPERS READ BEFORE THE CHEMICAL SOCIETY. By FRANCISJONES, F.R.S.E. THEexact composition of stibine has never been ascertained, owing chiefly to the fact that the gas has not been obtained unmixed with hydrogen : nor does it appear likely that the gas can be prepared in the pure state, owing to its tendency to split up into antimony and hydro- gen even at the ordinary temperature. Nevert'heless it seemed to me not impossible to devise a method for the analysis of the gas even when mixed with hydrogen, and I have made a series of experiments in this direction, the results of which I propose to lay before the Society. In the course of these experiments 1 had occasion to examine the properties of the gas and the different methods proposed for its prepa- ration. These are: (a.) By the action of acids on an alloy of zinc and antimony. (b.) By the addition of a solution of antimony to a mixture of zinc and a dilute acid. (c.) By the action of sodium-amalgam on a concentrated solution of antimony trichloride (Humpert, Chem. Ceiztr., 1865, 863). The first and second methods yield a very impure gas (that is, a gas mixed with much hydrogen), and although the last gives a much purer product, it is unsuitable when large quantities are required. A more Published on 01 January 1876. Downloaded by University of Illinois at Chicago 27/10/2014 19:37:02. convenient method consists in allowing a strong solution of antimony in hydrochloric acid to drop on a considerable bulk of zinc either granu- lated or in powder. -

CSAT Top-Screen Questions OMB PRA # 1670-0007 Expires: 5/31/2011

CSAT Top-Screen Questions January 2009 Version 2.8 CSAT Top-Screen Questions OMB PRA # 1670-0007 Expires: 5/31/2011 Change Log .........................................................................................................3 CVI Authorizing Statements...............................................................................4 General ................................................................................................................6 Facility Description.................................................................................................................... 7 Facility Regulatory Mandates ................................................................................................... 7 EPA RMP Facility Identifier....................................................................................................... 9 Refinery Capacity....................................................................................................................... 9 Refinery Market Share ............................................................................................................. 10 Airport Fuels Supplier ............................................................................................................. 11 Military Installation Supplier................................................................................................... 11 Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) Capacity................................................................................... 12 Liquefied Natural Gas Exclusion -

Lists of Gases for Pcard Manual.Xlsx

GASES THAT ARE PROHIBITED FROM PURCHASE WITH A P-CARD (Please note, this list is not all-inclusive. It is maintained by the Office of Research Safety. The office can be contacted at 706-542-9088 with any questions or comments.) Gas CAS Number Hazards Ammonia 7664‐41‐7 Corrosive Highly toxic, Arsine 7784–42–1 flammable, pyrophoric Boron tribromide 10294–33–4 Toxic, corrosive Boron trichloride 10294–34–5 Corrosive Boron trifluoride 7637–07–2 Toxic, corrosive Highly toxic, Bromine 7726–95–6 corrosive Toxic, Carbon monoxide 630–08–0 flammable Toxic, corrosive, Chlorine 7782–50–5 oxidizer Chlorine dioxide 10049–04–4 Toxic, oxidizer Chlorine trifluoride 7790–91–2 Toxic, oxidizer, corrosive Highly toxic, Diborane 19278–45–7 flammable, Dichlorosilane 4109–96–0 Toxic, corrosive Ethylene oxide 75–21–8 Toxic, flammable Highly toxic, corrosive, Fluorine 7782–41–4 oxidizer Highly toxic, Germane 7782–65–2 flammable Hydrogen bromide 10035–10–6 Toxic, corrosive Hydrogen chloride 7647–01–0 Toxic, corrosive Hydrogen cyanide 74–90–8 Highly toxic, flammable Hydrogen fluoride 7664–39–3 Toxic, corrosive Hydrogen iodide 10034‐85‐2 Toxic, corrosive Highly toxic, Hydrogen selenide 7783–07–5 flammable Toxic, flammable, Hydrogen sulfide 7783–06–4 corrosive Methyl bromide 74–83–9 Toxic Methyl isocyanate 624‐83‐9 Highly toxic, flammable Methyl mercaptan 74–93–1 Toxic, flammable Nickel carbonyl 13463–39–3 Highly toxic, flammable Highly toxic, Nitric oxide 10102–43–9 oxidizer Highly toxic, Nitrogen dioxide 10102–44–0 oxidizer, corrosive Highly toxic, Ozone 10028‐15‐6 -

Bismuth Trihydride and Silver Bismuthide

no NATURE [NOVEMBER 14, 1925 uncontaminated with any chloride. The di Bismuth Trihydride and Silver Bismuthide. hydride was reduced in accordance with the equation : GAsEous bismuth hydride was first prepared by 2Bi H + H = 2BiH + 2Bi. Paneth (Ber., 1918, sr, 1704), who obtained it by 2 2 2 3 treating an alloy of magnesium and thorium C or Paneth has pointed out that the yields of bis radium C with 0·2 normal hydrochloric sulphuric muthine prepared from his alloys were very variable, acid. He afterwards (ibid. p. 1728) prepared some and he concluded that the action of acids upon the what larger quantities of the gas by the action of alloys cannot be one of simple decomposition, since either of the above acids (but of four times normal the best yields were obtained from magnesium which strength) upon an alloy of bismuth and magnesium, was merely coated with fused metallic bismuth. A carrying out the reaction in a heated iron crucible possible explanation of this is that Paneth made a and in a stream of hydrogen. A mirror of bismuth coating of dihydride upon the magnesium was obtained when the issuing gas was heated as as soon as the acid acted upon the alloy. This view it passed through a glass tube. The gas was, is supported by the work of one of us (E. J. W., however, never obtained in large quantities, and we Chem. News, 1923, 127, 87), in which it was shown have endeavoured to make a considerable amount of that the yields of stibine from alloys of antimony this hydride and from this substance to isolate the and zinc appear to be independent of the composition silver bismuthide, analogous to silver antimonide of the alloy. -

Structural Evidence for Pnictogen-Centered Lewis Acidity in Cationic Platinum-Stibine Complexes Featuring Pendent Amino Or Ammonium Groups †

molecules Article Structural Evidence for Pnictogen-Centered Lewis Acidity in Cationic Platinum-Stibine Complexes Featuring Pendent Amino or Ammonium Groups † Roberta R. Rodrigues and François P. Gabbaï * Department of Chemistry, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-3255, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-979-862-2070 † In memory of Alan H. Cowley, a most inspiring Ph.D. advisor, and a great friend. Abstract: As part of our continuing interest in the chemistry of cationic antimony Lewis acids as ligands for late transition metals, we have now investigated the synthesis of platinum complexes featuring a triarylstibine ligand substituted by an o-[(dimethylamino)methyl]phenyl group referred N N to as Ar . More specifically, we describe the synthesis of the amino stibine ligand Ph2SbAr (L) and its platinum dichloride complex [LPtCl]Cl which exists as a chloride salt and which shows weak coordination of the amino group to the antimony center. We also report the conversion of [LPtCl]Cl 3+ into a tricationic complex [LHPt(SMe2)] which has been isolated as a tris-triflate salt after reaction of [LPtCl]Cl with SMe2, HOTf and AgOTf. Finally, we show that [LHPt(SMe2)][OTf]3 acts as a catalyst for the cyclization of 2-allyl-2-(2-propynyl)malonate. Citation: Rodrigues, R.R.; Gabbaï, Keywords: pnictogen bonding; platinum; catalysis F.P. Structural Evidence for Pnictogen-Centered Lewis Acidity in Cationic Platinum-Stibine Complexes Featuring Pendent Amino or 1. Introduction Ammonium Groups . Molecules 2021, The chemistry of stibines is attracted a renewed interest because of applications in 26, 1985. -

TIH/PIH List

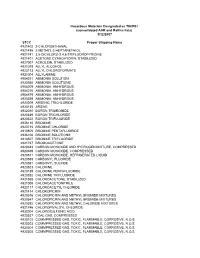

Hazardous Materials Designated as TIH/PIH (consolidated AAR and Railinc lists) 3/12/2007 STCC Proper Shipping Name 4921402 2-CHLOROETHANAL 4921495 2-METHYL-2-HEPTANETHIOL 4921741 3,5-DICHLORO-2,4,6-TRIFLUOROPYRIDINE 4921401 ACETONE CYANOHYDRIN, STABILIZED 4927007 ACROLEIN, STABILIZED 4921019 ALLYL ALCOHOL 4923113 ALLYL CHLOROFORMATE 4921004 ALLYLAMINE 4904211 AMMONIA SOLUTION 4920360 AMMONIA SOLUTIONS 4904209 AMMONIA, ANHYDROUS 4904210 AMMONIA, ANHYDROUS 4904879 AMMONIA, ANHYDROUS 4920359 AMMONIA, ANHYDROUS 4923209 ARSENIC TRICHLORIDE 4920135 ARSINE 4932010 BORON TRIBROMIDE 4920349 BORON TRICHLORIDE 4920522 BORON TRIFLUORIDE 4936110 BROMINE 4920715 BROMINE CHLORIDE 4918505 BROMINE PENTAFLUORIDE 4936106 BROMINE SOLUTIONS 4918507 BROMINE TRIFLUORIDE 4921727 BROMOACETONE 4920343 CARBON MONOXIDE AND HYDROGEN MIXTURE, COMPRESSED 4920399 CARBON MONOXIDE, COMPRESSED 4920511 CARBON MONOXIDE, REFRIGERATED LIQUID 4920559 CARBONYL FLUORIDE 4920351 CARBONYL SULFIDE 4920523 CHLORINE 4920189 CHLORINE PENTAFLUORIDE 4920352 CHLORINE TRIFLUORIDE 4921558 CHLOROACETONE, STABILIZED 4921009 CHLOROACETONITRILE 4923117 CHLOROACETYL CHLORIDE 4921414 CHLOROPICRIN 4920516 CHLOROPICRIN AND METHYL BROMIDE MIXTURES 4920547 CHLOROPICRIN AND METHYL BROMIDE MIXTURES 4920392 CHLOROPICRIN AND METHYL CHLORIDE MIXTURES 4921746 CHLOROPIVALOYL CHLORIDE 4930204 CHLOROSULFONIC ACID 4920527 COAL GAS, COMPRESSED 4920102 COMMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920303 COMMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920304 COMMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920305 COMMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920101 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920300 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920301 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920324 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920331 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, CORROSIVE, N.O.S. 4920165 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, N.O.S. 4920378 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, N.O.S. 4920379 COMPRESSED GAS, TOXIC, FLAMMABLE, N.O.S. -

Species Analysis of Inorganic Compounds in Workroom Air by Atomic Spectroscopy

ANALYTICAL SCIENCES VOL. 7 SUPPLEMENT 1991 1029 SPECIES ANALYSIS OF INORGANIC COMPOUNDS IN WORKROOM AIR BY ATOMIC SPECTROSCOPY SIRI HETLAND', IVAR MARTINSEN', BERNARD RADZIUK2 and YNGVAR THOMASSEN' 1 National Institute of Occupational Health , P.O.Box 8149 DEP, N-0033 Oslo 1, Norway 2 Department of Applied Research , Bodenseewerk Perkin-Elmer GmbH, P.O.Box 10 11 64, D-7770 Uberlingen, Germany Abstract - Sampling methods for the determination of volatile inorganic compounds in workroom air are described. The main factor affecting the adsorption capacity of activated charcoal for iron pentacarbonyl is air flow rate. Nickel tetracarbonyl is collected quantitatively at flow rates of up to 11/min if the volume of air sampled does not exceed 1001. Arsine, phosphine and stibine are collected quantitatively from air by use of a double filter air cassette Silver nitrate impregnated backing pads are shown to trap the hydrides with better than 99.9% efficiency. Several atomic spectroscopic methods have been applied to the determination of these volatile species, with electrothermal atomic absorption and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy being preferred. Concentrations of the hydrides in various workroom atmospheres were found to be well below the Threshold Limit Values. Key words arsine, stibine, phosphine, iron pentacarbonyl, nickel tetracarbonyl, species analysis The term chemical species refers to a specific form (monatomic or molecular) or configuration in which an element can occur, or to a distinct groups of atoms consistently present in different compounds or matrices . The individual species may be gaseous, solid, crystalline or in solution depending upon the nature of the sample. A parent species is an unchanging component (e.g.