Comic Books, Science (Fiction) and Public Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Explorer Academy

CHILDREN’S BOOKS FALL 2018 & Complete Backlist WE’ RE JUMPING INTO FICTION! National Geographic Partners LLC, a joint venture between National Geographic Society and 21st Century Fox, combines National Geographic television channels with National Geographic’s media and consumer- oriented assets, including National Geographic magazines; National Geographic Studios; related digital and social media platforms; books; maps; children’s media; and ancillary activities that include travel, global experiences and events, archival sales, catalog, licensing and e-commerce businesses. A portion of the proceeds from National Geographic Partners LLC will be used to fund science, exploration, conservation and education through significant ongoing contributions to the work of the National Geographic Society. For more information, visit www.nationalgeographic.com and find us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Google+, YouTube, LinkedIn and Pinterest. National Geographic Partners 1145 17th Street NW Washington, D.C. 20036-4688 U.S.A. Get closer to National Geographic Explorers and photographers, and connect with other members around the globe. Join us today at nationalgeographic.com/join The domed ceiling of the lobby at National Geographic’s headquarters building in Washington, D.C., re-creates the starry sky on the night that National Geographic was founded on January 27, 1888. Staff use this spot as a landmark and often say, “Let’s meet ‘under the stars.’” Under the Stars books showcase characters and situations that reflect the work of renowned National Geographic scientists, photographers, and journalists, through fictional stories that are based on their adventures and discoveries. COVER: Illustration by Antonio Javier Caparo. Dear Readers, I am pleased to present our Fall 2018 list. -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

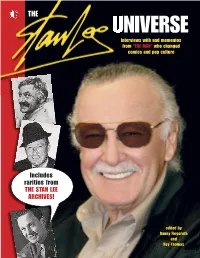

Includes Rarities from the STAN LEE ARCHIVES!

THE UNIVERSE Interviews with and mementos from “THE MAN” who changed comics and pop culture Includes rarities from THE STAN LEE ARCHIVES! edited by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas CONTENTS About the material that makes up THE STAN LEE UNIVERSE Some of this book’s contents originally appeared in TwoMorrows’ Write Now! #18 and Alter Ego #74, as well as various other sources. This material has been redesigned and much of it is accompanied by different illustrations than when it first appeared. Some material is from Roy Thomas’s personal archives. Some was created especially for this book. Approximately one-third of the material in the SLU was found by Danny Fingeroth in June 2010 at the Stan Lee Collection (aka “ The Stan Lee Archives ”) of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and is material that has rarely, if ever, been seen by the general public. The transcriptions—done especially for this book—of audiotapes of 1960s radio programs featuring Stan with other notable personalities, should be of special interest to fans and scholars alike. INTRODUCTION A COMEBACK FOR COMIC BOOKS by Danny Fingeroth and Roy Thomas, editors ..................................5 1966 MidWest Magazine article by Roger Ebert ............71 CUB SCOUTS STRIP RATES EAGLE AWARD LEGEND MEETS LEGEND 1957 interview with Stan Lee and Joe Maneely, Stan interviewed in 1969 by Jud Hurd of from Editor & Publisher magazine, by James L. Collings ................7 Cartoonist PROfiles magazine ............................................................77 -

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 Less Doctor Who Except for 1975

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 less Doctor Who except for 1975 Annual aa TITLE, EXCLUDING “THE”, c=circa where no © displayed, some dates internal only Annual 2000AD Annual 1978 b3 Annual 2000AD Annual 1984 b3 Annual-type Abba Gift Book © 1977 LR4 Annual ABC Children’s Hour Annual no.1 dj LR7w Annual Action Annual 1979 b3 Annual Action Annual 1981 b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 LR5 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 2, (1 for repair of other) b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Sir Lancelot circa 1958, probably no.1 b3 Annual TVT A-Team Annual 1986 LR4 Annual Australasian Boy’s Annual 1914 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual 1912 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual c/1930 plane over ship dj not matching? LR Annual Australian Girl’s Annual 16? Hockey stick cvr LR Annual-type Australian Wonder Book ©1935 b3 Annual TVT B.J. and the Bear © 1981 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1985 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1986 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1981 LR5 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1964 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1971 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1981 b3 Annual Beano Book 1983 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1985 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1987 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1976 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1977 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1982 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1987 LR4 Annual TVT Ben Casey Annual © 1963 yellow Sp LR4 Annual Beryl the Peril 1977 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual Beryl the Peril 1988 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual TVT Beverly Hills 90210 Official Annual 1993 LR4 Annual TVT Bionic -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form. Ralph Randolph Duncan II Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Panel Analysis: A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form. Ralph Randolph Duncan II Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Duncan, Ralph Randolph II, "Panel Analysis: A Critical Method for Analyzing the Rhetoric of Comic Book Form." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4910. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4910 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The qualityof this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copysubmitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

From the Renaissance to England's Golden

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY From the Martin Luther Renaissance to England’s Golden Age Reader Flying machine Queen Elizabeth I Printing press The Renaissance 1-89 The Reformation 91-145 England in the Golden Age 147-201 Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Copyright © 2017 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge®, Core Knowledge Curriculum Series™, Core Knowledge History and Geography™ and CKHG™ are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. -

Prince Valiant Vol.1: 1937-1938 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

PRINCE VALIANT VOL.1: 1937-1938 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Harold Foster | 120 pages | 18 Aug 2009 | Fantagraphics | 9781606991411 | English | Seattle, United States Prince Valiant Vol.1: 1937-1938 PDF Book Hastings Edition - Volume 1 - 1st printing. This is graphic storytelling at its finest and a true treasure! Prince Valiant. Categories : comics debuts Prince Valiant Fantagraphics Books titles Comic strip collection books. When Val encountered the witch Horrit, she predicted he would have a life of adventure, noting that he would soon experience grief. Prince Valiant in the Days of King Arthur 1. Flag as Inappropriate This article will be permanently flagged as inappropriate and made unaccessible to everyone. Issue 1-REP. Comic strip aficionados will be ecstatic, and younger readers who enjoy a classic adventure yarn will be bowled over. Published May by Blackthorne. Fantagraphics Books 16 February Currently, the strip appears weekly in more than American newspapers, according to its distributor, King Features Syndicate. Published by Pioneer. Official Prince Valiant Annual 1. Foster continued to write the continuity until strip in Add to cart Very Fine. Fantagraphics Hal Foster prince valiant. Fantagraphics Books 7 September Volume One is rounded out with a rare, in-depth classic Foster interview previously available only in a long out-of-print issue of The Comics Journal , as well as an informative Afterword detailing the production and restoration of this edition. Prince Valiant has previously been widely available only in re-colored, somewhat degraded editions now out of print and fetching collectors' prices. Stories and art by Hal Foster. With these words Karen and Valeta, the twin daughters of Prince Valiant and Queen Aleta, returned August 7, , to the Sunday adventure strip that bears their father's name. -

Hail to the Caldecott!

Children the journal of the Association for Library Service to Children Libraries & Volume 11 Number 1 Spring 2013 ISSN 1542-9806 Hail to the Caldecott! Interviews with Winners Selznick and Wiesner • Rare Historic Banquet Photos • Getting ‘The Call’ PERMIT NO. 4 NO. PERMIT Change Service Requested Service Change HANOVER, PA HANOVER, Chicago, Illinois 60611 Illinois Chicago, PAID 50 East Huron Street Huron East 50 U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Association for Library Service to Children to Service Library for Association NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT PENGUIN celebrates 75 YEARS of the CALDECOTT MEDAL! PENGUIN YOUNG READERS GROUP PenguinClassroom.com PenguinClassroom PenguinClass Table Contents● ofVolume 11, Number 1 Spring 2013 Notes 50 Caldecott 2.0? Caldecott Titles in the Digital Age 3 Guest Editor’s Note Cen Campbell Julie Cummins 52 Beneath the Gold Foil Seal 6 President’s Message Meet the Caldecott-Winning Artists Online Carolyn S. Brodie Danika Brubaker Features Departments 9 The “Caldecott Effect” 41 Call for Referees The Powerful Impact of Those “Shiny Stickers” Vicky Smith 53 Author Guidelines 14 Who Was Randolph Caldecott? 54 ALSC News The Man Behind the Award 63 Index to Advertisers Leonard S. Marcus 64 The Last Word 18 Small Details, Huge Impact Bee Thorpe A Chat with Three-Time Caldecott Winner David Wiesner Sharon Verbeten 21 A “Felt” Thing An Editor’s-Eye View of the Caldecott Patricia Lee Gauch 29 Getting “The Call” Caldecott Winners Remember That Moment Nick Glass 35 Hugo Cabret, From Page to Screen An Interview with Brian Selznick Jennifer M. Brown 39 Caldecott Honored at Eric Carle Museum 40 Caldecott’s Lost Gravesite . -

Rachel Chandler by Caleigh Azumaya

MPB GSA NEWSLETTER Molecular Physiology & Biophysics 2016 Graduate Student Association Fall The purpose of UPCOMING EVENTS this newsletter October 7th: Coffee hour with Dr. Richard Simerly is to serve as a October 14th: MPB Relay Race - 5pm at the Rec Center Field House! resource for MPB students October 28th: Halloween Party & Costume Contest to get to know November 4th: Coffee hour with Dr. Ray Blind the department November 10th: Internal Student Invited Speaker better. December 9th: Holiday Cocoa, Coffee, and Cookie Decor! Coffee Hours By Merla Hubler The MPB GSA is excited to host another semester of coffee hours. Over the last years, students have enjoyed this opportunity to meet with faculty and staff and share life stories and pastries. Join us this semester! It’s a great way to meet the department and start your Friday with stories, coffee, and a smile. Please note the special coffee hour in December that will Friday, October 7 – Dr. Richard Simerly involve cocoa, coffee, and Friday, November 4 – Dr. Ray Blind cookie decoration! Friday, December 9 — Holiday Cocoa, Coffee, & Cookie Décor! New MPB GSA Officers President: Caleigh Azumaya Vice-President: Diane Saunders The GSA would like to thank the prior officers for their contributions. We are looking forward to a great year of Treasurer: Karin Bosma organizing events and outreach opportunities for the MPB Secretary: Roxana Loperana department faculty, post docs, and students. One of our Social Media Chair: Joey Elsakr goals is to continue to increase student involvement and camaraderie this year. Please contact any of the officers Seminar Chair: Bethany Dale with recommendations, critiques or ideas. -

COMICS and ILLUSTRATIONS PARIS – 14 MARCH 2015 Highlights Exhibited on Preview in NEW YORK from February 27Th to March 4Th

& Press Release ǀ PARIS ǀ 11 February 2015 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE COMICS and ILLUSTRATIONS PARIS – 14 MARCH 2015 Highlights exhibited on preview in NEW YORK from February 27th to March 4th Spirou et FantasioSpirou et Cauvin par Fournier Franquin GREG Janry Morvan * Munuera Nic Roba Tome Vehlmann Yann Yoann © Dupuis 2015 Philippe Francq Uderzo André Franquin Detail of an original illustration for Dior, 2001 Colour cover of Pilote n°489, 20 March 1969 Detail of an original board, Spirou et Fantasio, Estimate: €12,000-15,000 Estimate: €100,000-120,000 Spirou et les Hommes-Bulles, 1960 * © Francq © 2015 Goscinny - Uderzo Estimate: €70,000-80,000 Paris - Following the success of the Comics and Illustration inaugural auction in Paris in April 2014, which realised over €4M, Christie’s will hold a second auction dedicated to sequential art on the upcoming 14 March. This sale, once again carried out in partnership with the Daniel Maghen Gallery, will represent a wide selection of comic artists and heroes, of which the highlights will be exhibited during a preview held at Christie’s New York from February 27th until March 4th 2015. Daniel Maghen, auction expert: «The greatest names in comic history will be celebrated, such as the legendary characters of Hergé, Tintin and Captain Haddock, in an exceptional original cover of the Journal de Tintin, estimated between €350,000 and €400,000, as well as Edgar P. Jacobs’ Blake and Mortimer, and Albert Uderzo’s Astérix and Obélix. The «new classics» will also be represented along with Moebius, whose colour cover of the Incal and a page of Arzach will be offered.