Economic Survey in Norway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnologia Scandinavica 2019

Contents Papers vetenhet i Gamlakarleby socken 1740‒1800. Rev. by Mikkel Venborg Pedersen 3 Editorial. By Lars-Eric Jönsson 199 Religion as an Equivocal Praxis in the European 5 Tales from the Kitchen Drawers. The Micro- Union. Helene Rasmussen Kirstein, Distinktio- physics of Modernities in Swedish Kitchens. By nens tilsyneladende modsætning. En etnologisk Håkan Jönsson undersøgelse af religionsbegrebets flertydighed 22 Reading the Reindeer. New Ways of Looking at som mulighedsbetingelse for europæiske kirkers the Reindeer and the Landscape in Contemporary position i EU’s demokrati. Rev. by Sven-Erik Husbandry. By Kajsa Kuoljok Klinkmann 40 Sensations of Arriving and Settling in a City. 201 Fieldwork into Fandom. Jakob Löfgren, …And Young Finnish Rural Out-migrants’ Experiences Death proclaimed ‘Happy Hogswatch to all and with Moving to Helsinki. By Lauri Turpeinen to all a Good Night.’ Intertext and Folklore in 56 Returnees’ Cultural Jetlag. Highly Skilled Profes- Discworld-Fandom. Rev. by Tuomas Hovi sionals’ Post-Mobility Experiences. By Magnus 204 Fleeting Encounters with Birds and Birdwatchers. Öhlander, Katarzyna Wolanik Boström & Helena Elin Lundquist, Flyktiga möten. Fågelskådning, Pettersson epistemisk gemenskap och icke-mänsklig karis- 70 Danish Gentlemen around 1900. Ideals, Culture, ma. Rev. by Carina Sjöholm Dress. By Mikkel Venborg Pedersen 206 Finnish War Children in Sweden. Barbara Matts- 92 Narrating and Relating to Ordinariness. Experi- son, A Lifetime in Exile. Finnish War Children in ences of Unconventional Intimacies in Contem- Sweden after the War. An Interview Study with a porary Europe. By Tone Hellesund, Sasha Rose- Psychological and Psychodynamic Approach. neil, Isabel Crowhurst, Ana Cristina Santos & Rev. by Florence Fröhlig Mariya Stoilova 209 Work-Life Orientations for Ethnologists. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter Utgivna Av Statsvetenskapliga Föreningen I Uppsala 199

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 199 Secession och diplomati Unionsupplösningen 1905 speglad i korrespondens mellan UD, beskickningar och konsulat Redaktörer: Evert Vedung, Gustav Jakob Petersson och Tage Vedung 2017 © Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala och redaktörerna 2017 Omslagslayout: Martin Högvall Omslagsbild: Tage Vedung, Evert Vedung ISSN 0346-7538 ISBN 978-91-513-0011-5 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-326821 (http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-326821) Tryckt i Sverige av DanagårdLiTHO AB 2017 Till professor Stig Ekman Till minnet av docent Arne Wåhlstrand Inspiratörer och vägröjare Innehåll Förord ........................................................................................................ ix Secession och diplomati – en kronologi maj 1904 till december 1905 ...... 1 Secession och diplomati 1905 – en inledning .......................................... 29 Åtta bilder och åtta processer: digitalisering av diplomatpost från 1905 ... 49 A Utrikesdepartementet Stockholm – korrespondens med beskickningar och konsulat ............................................................. 77 B Beskickningar i Europa och USA ................................................... 163 Beskickningen i Berlin ...................................................................... 163 Beskickningen i Bryssel/Haag ......................................................... 197 Beskickningen i Konstantinopel ....................................................... 202 Beskickningen -

Page 01 June 06.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Thursday 6 June 2013 27 Rajab 1434 - Volume 18 Number 5722 Price: QR2 QE to woo Nadal, Djokovic more foreign to clash in French investment Open semis Business | 21 Sport | 32 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Bahrain probe Qatar Foundation signs MoU OPINION Qaradawi, Hezbollah and sectarian war into Hezbollah his Tweek Germany warned against business links arming Syrian rebels on the ground Other GCC nations urged to follow suit that it might lead Khalid Al Sayed DOHA: Some seven years after the whole region,” said a commen- to sectar- EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Hezbollah and its leader Sayyed tator on Alarabia.net yesterday. ian war, Hassan Nasrallah were cel- “If Arab leaders want stability but those watching the ebrated as heroes in the GCC in their countries, they must ban Syrian uprising might have region and the rest of the Arab Hezbollah’s activities in their ter- noticed that the sectarian world for their victory over ritories.” Another commentator war has already started — Israel, the tables seem to be writing on the web portal called with Hezbollah chief Hassan turning against the militant for a ban on Shias in (Arab and Nasrallah’s speech. He openly outfit as it intervenes in Syria GCC states) so “they abandon declared his support for the and goes on a killing spree their pro-Iran agenda”. Bashar Al Assad regime and against Sunni rebels. Yet another suggested that if sent his people to Syria to Just days after the GCC sec- the GCC states boycott Hezbollah, fight alongside Assad’s forces, retary-general, Abdullatif Al “100s of thousands of Lebanese H H Sheikha Moza bint Nasser and Prince Charles witnessing the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding declaring that he would not Zayani, condemned Hezbollah for Shia based in the region would be between Qatar Foundation and the Prince of Wales’ Charitable Foundation that will focus on developing give terrorists a chance to interfering in Syria, Bahrain yes- driven away. -

Reelle Hensyn” I Norsk Rettstenkning

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives ”Reelle hensyn” i norsk rettstenkning Stian Haldsrud Masteroppgave Institutt for statsvitenskap UNIVERSITETET I OSLO 10. mai 2006 2 INNHOLD Forord……………………………………………………………………………..…5 1.0 INNLEDNING, PROBLEMSTILLING OG METODE………………….....6 1.1 Innledning med problemstilling………………………………………………....6 1.2 Metode…………………………………………………………………………..8 1.3 God latin i statsvitenskapen?...............................................................................12 2.0 REELLE HENSYN SOM BEGREP………..………………………………..15 2.1 Alf Ross……………………………………………………………………..….15 2.2 Carl August Fleischer.………………………………………………………….16 2.3 Torstein Eckhoff………………………………………………………………..22 2.4 Jens Evald………………………………………………………………….…...26 2.5 Fredrik Sejersted…………………………………………………………….….27 2.6 Sverre Blandhol………………………………………………………………....28 2.7 Morten Kinander………………………………………………………………..30 2.8 Min forståelse. Begrepets utvikling………………………………………….…34 2.8.1 Bred og snever bruk av reelle hensyn…………………………………38 2.8.2 Begrepsutviklingen…………………………………………………....40 3.0 REELLE HENSYN I RETTSPRAGMATISME OG RETTSREALISME.50 3.1 Innledning………………………………………………………………………50 3.2 Anton Martin Schweigaard – vår første pragmatiker…………………………..53 3.3 Konsesjonssaken…………………………………………………………….….56 3.3.1 Kristiania Byrett 1913………………………………………………....58 3.3.2 Høyesterett 1918……………………………………………………....59 3.4 Fullmaktslovgivningen ………………………………………………………....62 3.5 Drøfting………………………………………………………………………....68 3.5.1 -

Sparebank 1 Nord-Norge Annual Report 2018

SPAREBANK 1 NORD-NORGE ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY OPERATIONS ANNUAL ACCOUNTS 2018 SPAREBANK 1 NORD-NORGE CONTENTS TABLE OF OF TABLE SPAREBANK 1 NORD-NORGE 1 SPAREBANK 06 From the CEO SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge 10 Strategic compass 12 Historical background 14 Important events in 2018 16 SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge’s branches 17 Organisational Chart and Company Structure 18 Annual report 22 Annual report from the Board ANNUAL ACCOUNTS Annual accounts 2018 48 Annual report – Income statement 49 Annual report – Balance Sheet 50 Annual report – Changes in equity 52 Annual report – Cash flow Statement 53 Annual report – Notes 146 Declaration by the Board of Directors and CEO 2018 147 Auditor’s report Operations 156 Group management 158 Board of Directors 160 Governing bodies OPERATIONS 162 Corporate governance in SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge 176 Risk management and internal control 183 Ownership 191 Operations 198 SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge Markets 200 SpareBank 1-alliance 204 The Foundations 206 Organisation and HR CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY SOCIAL CORPORATE Corporate social responsibility 216 Global Reporting Intiative (GRI) 221 Sustainability 232 Samfunnsløftet Photo annual report 2018: Edvard Kristiansen, Marius Fiskum, Tom Benjaminsen and Perspektivet Museum. A STABLE REGION IN SPAREBANK 1 NORD-NORGE 1 SPAREBANK AN UNSTABLE WORLD 4 2018 was a year characterised by global instability. Climate change, trade wars, Brexit and #metoo have filled our news channels. olitical instability in normally stable coun- Our owners obviously benefit from good results. tries such as Sweden were symptoms Equity certificate holders will receive a dividend of that completed the picture. Despite this, NOK 4 per equity certificate. -

Johan Castberg Og De Castbergske Barnelover EN STOR MANN FRA

Johan Castberg og de Castbergske barnelover EN STOR MANN FRA LILLE BREVIK På fjellveggen i Kastanjehagen i Brevik henger en minneplate over en mann fra Brevik som ikke så mange vet hvem er. Hans navn er Johan Castberg. Han var født i Brevik 21. september 1862, og døde i Oslo 24. desember 1926. Oppvekst i Brevik Høsten 1862 ble en gutt med navn Johan Castberg født i Brevik. Han ble oppkalt etter sin far som het Johan Christian Tandberg Castberg. Faren var opprinnelig fra Fredrikstad, og det var hans jobb ved Brevik Tollsted som førte familien til Telemark. Moren het Hanna Magdalene Castberg, født Frisak Ebbesen. Hun var født i Risør. Familien kom til Brevik i 1858. De bodde på Sylterøya, i Kirkegaten 16. Eiendommen inneholdt den gang et stort og et lite hus, i tillegg til en fløybygning mot nord som inneholdt vedskjul og utedo. Det var ikke innlagt vann. En felles vannpost sto utenfor porten øverst i krysset Skipsbakken/Kirkegaten. Det minste huset ble senere revet for å utvide veien ned til Blikkvarefabrikken. Hovedhuset, hvor familien Castberg bodde, brant i 1952. Ny bolig ble reist på eiendommen av Trygvde og Herdis Thorsen. Boligen eies i 2016 av Andrè Knudsen og Jesper Nilsen, som har pusset opp og modernisert huset. Familien Castberg var en fruktbar familie, og hadde til sammen 13 barn. De 9 første ble født i Brevik. Ved folketellingen i 1865 bodde følgende i Kirkegata 16: Far Johan 39 år, mor Hanna 27 år og 4 barn, Margrethe 6 år, Jørgen 5 år, Johan 4 år og Einar 2 år. -

Annual Report

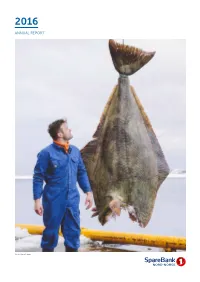

2016 ANNUAL REPORT Photo: Marius Fiskum 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Cover photo 03 Historical background 04 Organisational chart Fisheries for generations 05 Annual report Ingvard Lorentzen is a fourth 08 Important events in 2016 generation fish buyer at 09 Vision and business consept Brensholmen outside Tromsø. 10 From the CEO The company was established 13 Report of the Board of Directors by his great grandfather in 1896. Ingvard succeeded his 35 ANNUAL ACCOUNTS 2016 father in 2002. The company Ivan Lorentzen Fiskeforretning 36 Income statement AS is particularly well-known 37 Balance sheet 38 Total liabilities and equity for its award-winning lutefisk. 40 Cash flow statement 41 Notes 120 Statement from the Board of Directors and chief executive officer 121 Auditor's report 127 OPERATIONS 128 Group management 130 Board of Directors 132 Governing bodies 134 Corporate governance 143 Risk management, internal control and capital management 156 Ownership 160 Operations 163 SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge Markets 164 SpareBank 1 Alliance and SpareBank 1 Gruppen 167 Employees 171 Corporate social responsibility 175 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 176 Together we make things happen 177 This is worth a lot to us 178 Teaming up with skiing in Northern Norway 180 Prize for putting finance on the timetable 182 Unforgettable party in Bodø 184 Commendable cycle event 03 IT STARTED HERE: SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge’s history started with the establishment of Tromsø Sparebank in 1836 – the first savings bank in the region. Today’s SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge is the result of the merger of about 40 savings banks in Northern Norway. -

Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register

Nomination form International Memory of the World Register The Castbergian Child Laws of 1915 ID Code [2016-03] 1.0 Summary (max 200 words) In 2015 Norway celebrated the centenary of The Castbergian Child Laws. The laws regarding the welfare of children were named after the politician Johan Castberg, who was the primary driving force behind the ground-breaking reform. The Castbergian Child Laws were highly progressive for their time, giving so-called illegitimate children equal inheritance rights from both parents regardless of their marital status, and the right to the paternal name. Despite being criticized for undermining traditional family values and promoting promiscuity, the laws were passed on 10th April 1915. Norway was among the first countries to pass new laws on the status of extra-marital children. This provided an example for other Nordic and European countries. According to the new laws, both parents were obliged to provide for the child born outside marriage. If the father was unwilling or unable to pay, the mother was entitled to some financial support. It was also seen as crucial to reduce child mortality and prevent hidden pregnancies which happened more frequently outside marriage. The Parliamentary Archives of Norway wish to nominate the archival material documenting this legislative process. The material includes petitions handed over to Parliament by organizations and individuals from across the country. 2.0 Nominator 2.1 Name of nominator (person or organization) Archives of the Storting [the Parliamentary Archives -

The League of Nations Starts; an Outline by Its Organisers

I ^^cL.<^i ^r/^ ^ THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS STARTS MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAV • CALCUTTA • MADRAS MELBOURNB THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON - CHICAGO DALLAS • SAN FRANCISCO THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS STARTS AN OUTLINE BY ITS ORGANISERS MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED ST. MARTIN'S STREET, LONDON 1920 ii , r COPYRIGHT FOREWORD The League of Nations is commonly spoken of as if it were a closely knit, compact entity, directed by a clearly defined individuality. It is almost never visualised as a co-operative association wherein the nations seek to overcome their mutual differences by means of a complex organization ramifying through many fields of international interest. We speak of " The League " much as we speak of " England " or " Italy," but whereas with individual countries the appellation con- notes aU the separate actions of government, in the case of the League, unfortunately, it brings to mind merely a single, very general, abstract principle. If this error is natural because of the extreme newness of the League, it is none the less dangerous because -of the tendency which it fosters to prevent our analysing the actual structure and method of operation of the League. Just as it is essential to the success of national governments to under- stand exactly what their duties and powers are, so, but to a still greater degree, is it essential to know what are the duties and powers of a League embracing most of the civilised world. The League, indeed, can be analysed in just the same way as any other human association. -

IFS Arbok 1985.Pdf (5.667Mb)

FORSVARSSTUDIER Defence Studies IV ©Forlaget TANO 1985 ISSN 0333-3981 ISBN 82-518-2090-1 Engers Boktrykkeri A/S, Otta Innhold Forord . 7 Foreword . 12 T.M. Hetland: Då Moskva sa nei til Norden. Sovjets syn på Norden og NATO 1948-1952 . 13 English Summary . 61 T.M. Hetland: Atomrasling og avspenning. Sovjet og norsk tryggingspolitikk 1953-1958 . 63 English Summary . 108 R. Berg: «Det land vi venter hjælp af». England som Norges beskytter 1905-1908 . Ill English Summary . 165 J. Sanness: Norske historikere og den kalde krigen . 169 English Summary . 184 O. Wicken: Våpenimport eller egenproduksjon? Hvorfor Norge ikke bygde ut militær industri 1945-1950 186 English Summary . 223 F. Fagertun: Militærmakten og <<den indre fiende» 1918-1940 ...................................... 225 English Summary .................................. 268 Bidragsytere . 271 Notes on contributors ............................... 271 Forord FHFS - Forsvarshistorisk forskningssenter - presenterer med dette FORSVARSSTUDIER IV. Bidragene i årboken, som er skrevet av institusjonens faste forskere og andre spesielt inviterte, er basert på mye ny forskning, og gir derfor et vell av nye opplysninger om viktige og til dels dramatiske sikkerhetspolitiske begivenheter i vår samtid. Artiklene er tidligere utgitt i vår serie FHFS notat, og årboken inneholder alle notatene fra 1984, med unntak for et bidrag av professor Olav Riste om de historiske grunntrekk i norsk sikkerhetspolitikk. Denne publiseres i J.J. Holst (ed.), Norwegian Foreign Policy for the 1980's (Universitetsforla get Oslo og Oxford University Press, 1985). Årboken tar denne gangen opp tre hovedemner: Vårt forhold til Sovjet og til Vestmaktene i nyere tid, den norske militærindustris levekår i skyggen av billig våpenhjelp fra USA og til slutt redselen for revolt fra venstre i mellomkrigstiden. -

2005-3 Ombrukket 3 26-10-05 12:07 Side 31

2005-3 ombrukket 3 26-10-05 12:07 Side 31 SOSIOLOGI I DAG, ÅRGANG 35, NR. 3/2005 31-49 Republikk eller monarki? Forfatningsspørsmålet i 1905 Roy Andersen [email protected] Abstract In the aftermath of the European revolutions of the mid 19th century, republican ideals appeared within radical movements in Norway. The struggle against a state led by the bureaucratic elite and monarchal power gave new impetus to the republican movement, and many politicians of the Left party (Liberal) declared themselves to be republicans. But this was mainly a principle; republicanism never became a political demand within the Left party. The main priorities were reform subjects like the introduction of parliamentary power and increased national independ- ence. At the same time republicanism was undermined by the very same nationalism which nourished it. The view of the age of the sagas as a golden period where kings held the roles of heroes increased the legitima- cy of the monarchy. When the question of the constitution was raised in 1905, it was overshadowed by the desire to obtain international recogni- tion for Norway as a nation. Christian Michelsen, a republican, was broadly supported when the question was postponed until the crisis with Sweden was resolved. In the intervening time he changed his mind, and when the issue was again raised after the reconciliation in Karlstad, he whole-heartedly supported the maintenance of the monarchy. Considering Michelsen’s position in the eyes of the population after hav- ing masterminded the abolishment of the union with Sweden plus the fact that the republicans lost sympathy after the criticism of the Karlstad reconciliation, it is hardly surprising that an overwhelming majority both in parliament and in the referendum elected to maintain the monarchy. -

Government Response

UNOFFICIAL TRANSLATION OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL Oslo, 14 Dec. 2016 2016-0727 FSE/ANW NOTICE OF DEFENCE TO OSLO DISTRICT COURT C a s e N o : 16-166674TVI-OTIR/06 Plaintiff 1: Föreningen Greenpeace Norden BOX 15164 SE 104 65 Stockholm County of Stockholm Counsel: Advocate Cathrine Hambro Wahl-Larsen Advokatfirma AS Fr. Nansens pl. 5 NO-0160 OSLO Plaintiff 2: Natur og Ungdom Torggata 34 NO-0183 OSLO Counsel: Advocate Emanuel Feinberg Advokatfirmaet Glittertind AS PO Box 1384 Vika NO-0114 OSLO Defendant: The Government of Norway represented by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy PO Box 8148 NO-0033 OSLO Counsel: Office of the Attorney General represented by Attorney General Fredrik Sejersted PO Box 8012 NO-0030 OSLO Co-counsel: Advocate Anders F. Wilhelmsen, Attorney General Associate Ane Sydnes Egeland, Office of the Attorney General POSTAL ADDRESS: OSLO PHONE: + 47 22 99 02 00 / +47 22 99 02 01 VISITING ADDRESS: POSTBOKS 8012 DEP FAX: +47 22 99 02 50 UNIVERSITETSGATA 8 0030 OSLO E-MAIL: [email protected] OSLO OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL UNOFFICIAL TRANSLATION 1 INTRODUCTION I refer to the Notice of Proceedings dated 18 October 2016 and the Court’s letter dated 14 November where the deadline for filing a Notice of Defence was extended until 14 December, and declare myself Counsel for the Government of Norway represented by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (MPE). My co-counsel in the case will be Advocate Anders F. Wilhelmsen and Associate Ane Sydnes Egeland. A claim has been made in the Notice of Proceedings that the decision adopted by Royal Decree of 10 June 2016 concerning the award of production licences in the 23rd licensing round is invalid as it breaches Article 112 of the Norwegian Constitution.