Nu-Way Snaps and Snap Leads: an Important Connection in the History of Behavior Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 0 Y E a R S a Ttached to Y O U R N E E D S 2021 Catalog

800•624•2058 LIMITED LIFETIME WARRANTY RRAN A T Y W This icon denotes premium product warrantied by Fasnap® Corp. F CORP.® FASNAP A P SNA Product lines include: 4600 - 4647 - 4650 - 7058 - 7059 - 16000 - 18000 - GRM - SnapFast TM Fasnap® Corp., supports a LIMITED QUALITY PRODUCTS EXPERT SOLUTIONS LIFETIME WARRANTY on its Premium SINCE 1981 Brands of Snap Fasteners and Grommets. This warranty provides the assurance 574•264•1185 that our premium brand fasteners, when properly installed and maintained, used in FAX 574•264•0802 normal applications and under normal environmental conditions, are free from defect. Should these Premium Fasteners ever fail, Fasnap® Corp. will provide the original purchaser free replacement of the fastener. This warranty is limited to the original customer of Fasnap® Corp. or Fasnap’s authorized distributor and applies only to the Premium brands that Fasnap® Corp. offers to our customers. This warranty does not apply to products that fail due to improper installation or ED CH TO inadequate application design. This TA T Y warranty is voided should these Premium A O 407•816•9993 Brand Products be combined with any U other fasteners not covered by this S R warranty. Fasnap® Corp. reserves the R FAX 407•816•9933 N right to inspect any product or CATALOG 2021 A E application submitted for claim, and E E approve claims thereof. Y D 0 S 4 Fasnap® Premium Brands of Snap Fasteners and Grommets Series include: 2021 CATALOG 4647 4650 7058/7059 SOUTHWEST 16000 18000 GRM SNAPFAST® 714•528•1826 FAX 714•528•2416 PROTECT the value of YOUR product with the right FASTENERS by obtaining everything your company needs from fasnap.com R Pull•Click•Secure V-6.01 [04/06/21] COMPANY HISTORY METAL HARDWARE Fasnap® Corp. -

Catoosa County, GA

CCFD-2021-13 GENERAL SPECIFICATIONS PROTECTIVE JACKET AND PANTS FOR STRUCTURAL FIRE FIGHTING Catoosa County, GA SCOPE This specification details design and materials criteria to afford protection to the upper and lower body, excluding head, hands, feet, against adverse environmental effects during structural fire fighting. All materials and construction will meet or exceed NFPA Standard #1971 and OSHA for structural fire fighters protective clothing. _____Comply _____Exception OUTER SHELL MATERIAL - JACKETS AND PANTS The outer shell shall be constructed of TENCATE "AGILITY™ with ENFORCE™ technology” Kevlar®/PBO/ Nomex® blend material with an approximate weight of 6.6 oz. per square yard in a twill weave. The shell material must be treated with SST (SUPER SHELLTITE) which is a durable water-repellent finish that also enhances abrasion resistance. Color of the garments shall be black. Bids offering this shell material without the SST will not be considered. _____Comply _____Exception THERMAL INSULATING LINER - JACKET AND PANTS The thermal liner shall be constructed of TENCATE “QUANTUM3D™ SL2i”; a Kevlar® filament and FR rayon/para-aramid/nylon, spun yarn GoldcheckTM face cloth quilted to one flat layer and one three dimensional layer of Nomex®/Kevlar® spunlace with a finished weight of approximately 7.7 oz. per square yard. An approximate 7 inch by 9 inch pocket, constructed of self material and lined with moisture barrier material, shall be affixed to the inside of the jacket thermal liner on the left side by means of a lock stitch. The thermal liner shall be attached to the moisture barrier and bound together by bias-cut neoprene coated cotton/polyester around the perimeter. -

PANTS for WOMEN==Fas[1Ion and Fit

n PANTS FOR WOMEN==Fas[1ion and Fit Cooperative Extension Service Oregon State University Corvallis Extension Circular 742 October 1969 CONTENTS Pattern "Selection 3 Fabric Selection 3 Accurate Measurements 3 Pattern Preparation 3 Designing Your Own Pants 5 Pattern Layout and Cutting 6 Marking i . 6 Preparing for the First Fitting 6 Fitting 6 Common Fitting Problems 7 Posture and Figure Variations 8 Pants for Bowlegs 9 Stitching 10 Making Free-Hanging Linings 10 Preparing Waistbands 10 Applying Waistbands 12 Making Hems 12 Fants for Vv omen=-IT ash ion and Jrit ELAINE K. CARLSON Extension Clothing Specialist, Oregon State University Pants have become an important part of the modern wardrobe and may be worn for nearly every occasion. Even though the names and styles of pant-type garments change with fashion, the need for a good fit is always the same. The directions in this circular are for making pants with side seams, zipper placket, applied waistband, and a lining (optional). PATTERN SELECTION marked to indicate center front, center back, and both side seams. Use a three-inch strip of firmly woven fab- The pattern size is determined by the hip size, taken ric, folded in thirds to make a one-inch strip. Edge eight to nine inches below the waistline. This keeps pat- stitch both edges. Use different colored threads to indi- tern alterations to a minimum. Choose a pattern with a cate center markings and side markings. full-length leg, even though you plan to make shorter Record your measurements in the first column of the pants. -

Janesville Protective Clothing

INVITATION TO BID The Ware County Board of Commissioners is now accepting sealed bids for the purchase of Turn Out Gear and related equipment for the Ware County Fire Department. Ware County has no intention of purposely eliminating any company from bidding. However, there are certain specifications that must be met or exceeded. The Ware County Board of Commissioners reserves the right to reject any or all bids, with or without cause. Sealed bids will be accepted until Monday, March 7, 2011 and bids will be opened on that date at 10:30 a.m., at the Ware County Commission Office located at 800 Church Street, Suite 223, Waycross, Georgia. No late bids will be accepted. Awarding of the bid will take place at the next regular meeting of the Ware County Board of Commissioners and will be based on the lowest and/ or best bid. If you have any questions concerning this bid, you may call Elizabeth Hope at (912) 287-4300. Should your firm be interested in submitting a bid, please fill out the bid specification form, submit the sealed bid, marked on the outer envelope as “Turn Out Gear 2011” and mail or deliver to: Ware County Commission Elizabeth Hope 800 Church Street, Suite 223 Waycross, GA 31501 Ware County Fire / Rescue 1 of 17 Created on 2/23/2011 3:27:00 PM Ware County Fire Department Turn Out Gear Specifications 2011 SCOPE: The purpose of the clothing is to provide protection during structural fire fighting operations where there is a threat of fire or when certain physical hazards are likely to be encountered, such as during non-fire-related rescue operations, emergency medical operations, and victim extrication. -

Teamfood HACCP Clothing for the Food Industry

teamFOOD HACCP clothing for the food industry foodNorm foodRisk classes The protective function of workwear must correspond to the food hygiene risk and the type of work. When choosing medium and dark colours these should be selected so that any hygiene-relevant soiling occurring during work can be easily visibly recognised. Risk class 1 Low hygiene risk = Dealing with non-perishable Provides guidance and aims to make foodstuffs or ingredients it easier to adhere to regulatory • The protective function of the workwear with regard to the conditions of hygiene with regard to foodstuff may be low, if the foodstuff workwear when dealing with is sufficiently protected by packaging and/or an additional foodstuffs. further processing step will be taken by the manufacturer or Applies to all areas in which the consumer. foodstuffs are manufactured, handled or will be placed on the market. Risk class 2 Provides instructions for the manufacturing, selection, usage and High hygiene risk reprocessing of workwear in food processing facilities taking the = Dealing with unpackaged, perishable special requirements of the foodstuffs or ingredients respective workplace into • High protective function of the workwear is primarily consideration. required, where the foodstuffs will not be processed Objective: Avoiding adversely further and micro organisms in or on the foodstuff may impacting foodstuffs to protect the multiply. health of consumers. Risk class 3 Highest hygiene risk = Dealing with unpackaged, ready-to-eat, highly perishable foodstuffs. • The -

6/2015 Winter INSTRUCTIONS

6/2015 Winter INSTRUCTIONS Please read the following the buttonholes should be placed at Materials Press the garment’s seams as you go general instructions before regular intervals (6…9 cm) between Fabric requirements are based on a along and give the garment a final starting your project. these points. fabric width of 145…150 cm. Pre press when it is completed. How to choose the correct For reasons of clarity, some of the shrink the fabric before cutting either Practical tips size pattern markings (e.g. positions of by washing or by steaming it thor Velcro tapes and buttons) have only oughly. If you choose a different fabric Gathering: Adjust your sewing ma Children’s pattern sizes are primari been printed on the smallestsize from the one suggested in the maga chine as follows: Decrease the up ly chosen according to the child’s pattern of the design. Copy these zine, allow for matching up fabric pat per thread tension and increase the height, and the pattern measurements in the corresponding places on the tern and for cutting with nap when stitch length (stitch length 4...5). Sew are then adjusted to correspond to pattern size of your choice, measuring calculating the fabric requirement. two rows of gathering stitches 0.5 cm the child’s other body measurements. the distance of each marking from apart from each other on the right Take the measurements on top of thin the edge of the pattern piece. Large Choose the interfacing on the basis side of the edge to be gathered, plac underwear and compare them with pattern pieces have been printed of the fashion fabric’s color, quality, ing one row on the seamline and the size chart. -

Dress with Flared Skirt

Lekala 4747 Dress With Flared Skirt Dress With Flared Skirt - Sewing Pattern #4747 Recommendations on fabric: thin natural/mixed suiting fabrics. You will also need: fusible interfacing; 5 buttons; 1 snap-fastener. Seam allowances: all seams 1 cm; seam allowance for hem of dress – 2 cm. Note on seam allowances: - If the pattern has double contour the seam allowances are included. They are 1 cm unless specified otherwise. - If the pattern has single contour, the seam allowances are NOT included and need to be added when laying out the pattern. Note on length of fabric: Attention! The amount of fabric needed for your pattern is not included. It will depend on the selected pattern size, the width, and design of the fabric you plan to use. First, print all the paper patterns and lay them out at the width of fabric you plan to use (usually from 90 to 150 cm). Measure how much fabric you will need. Don't forget to account for pieces that need to be cut multiple times and pieces that are cut on the fold. CUTTING: Note on cutting: On the pattern pieces, “beam” means straight of grain. Lay out your pieces accordingly. Some pieces will be cut on the fold. This is noted on the pattern piece. Mark all notches and other design features such as pleats etc. from the pattern onto your fabric. When sewing the garment, pay attention to notches, they must match up. Main fabric: 1. Center back - cut 1 on fold 2. Side back - cut 2 3. Back belt - cut 1 4. -

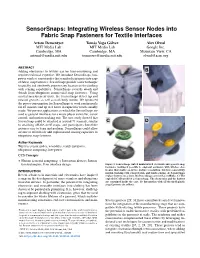

Sensorsnaps: Integrating Wireless Sensor Nodes Into Fabric Snap Fasteners for Textile Interfaces. Proc of UIST'19

SensorSnaps: Integrating Wireless Sensor Nodes into Fabric Snap Fasteners for Textile Interfaces Artem Dementyev Tomás Vega Gálvez Alex Olwal MIT Media Lab MIT Media Lab Google Inc. Cambridge, MA Cambridge, MA Mountain View, CA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Adding electronics to textiles can be time-consuming and A B requires technical expertise. We introduce SensorSnaps, low- power wireless sensor nodes that seamlessly integrate into caps of fabric snap fasteners. SensorSnaps provide a new technique to quickly and intuitively augment any location on the clothing with sensing capabilities. SensorSnaps securely attach and detach from ubiquitous commercial snap fasteners. Using inertial measurement units, the SensorSnaps detect tap and rotation gestures, as well as track body motion. We optimized the power consumption for SensorSnaps to work continuously for 45 minutes and up to 4 hours in capacitive touch standby mode. We present applications in which the SensorSnaps are used as gestural interfaces for a music player controller, cursor control, and motion tracking suit. The user study showed that SensorSnap could be attached in around 71 seconds, similar C D to attaching off-the-shelf snaps, and participants found the gestures easy to learn and perform. SensorSnaps could allow anyone to effortlessly add sophisticated sensing capacities to ubiquitous snap fasteners. Author Keywords Wireless sensor nodes, wearables, textile interfaces, ubiquitous computing, low-power CCS Concepts Human-centered computing -> Interaction devices; Interac- • tion techniques; User interface design Figure 1. SensorSnaps embed miniaturized electronics into generic snap fasteners, making it possible to augment garments with wireless elec- INTRODUCTION tronics that enable on-device gesture recognition, wireless connectivity, motion tracking with sensor fusion, and touch sensing. -

Wes Carpenter's Foreign Movies

This Issue’s Extravaganza: Wes Carpenter’s Foreign Movies November/December 2015 • Issue 58 • $10 USD pandamagazine.com From the Editor Issue 57 Completists #AAA Aardvarks (Rich Bragg, Jonathan McCue) • A Seer Who We’ve lost a number of prominent puzzle people this Argues (Adrian, Casey, Catherine, David, Eli, Rob) • Alison year. Henry Hook is one of the constructors, along with Muratore, Audrey Muratore, Eric Suess • J.H. Andersson • Mike Selinker and Patrick Berry, that helped inspire Ben Lowenstein • Black Fedora Group (Herman Chau, Lennart P&A Puzzle Magazine. Their work in Games Magazine Jansson, Nick Wu, Moor Xu, Eric Yu) • Joe Bohanon • Robert and Henry Hook’s $10,000 Trivia Contest gave me the Bosch • Nick Brady • Buzz Lime Pi (Jay Lorch, Jonathan desire to write interconnected puzzle suites. Henry Hook Anderson, Josie Naylor, Michelle Teague, Robb Effinger, Sarah passed away in October at 60, far too young. Caley, Sean McCarthy, Sean Osborn) • Jeremy Conner • Dan Katz, Jackie Anderson, & Steve Katz • Das Zauberboot (Mike, Big thanks to Joe Cabrera for the cover, and for the new Catherine, Dan, Donna, Becky) • DelphiRune (Steve & Anita) cover layout. • Joseph DeVincentis • Martin Doublesin • Doug Orleans & Paula Wing • david edwards • Joe Fendel • Dustin Foley • Foggy Brume Nathan Fung • Lily Geller • GUToL (Angel Bourgoin, Keith Bourgoin, Dan Moren, Evan Ritt) • Mark Halpin • Chris Harris Issue 57 Top Ten • David Harris • Paul Hlebowitsh • Brent Holman • Illegal Phlogizote (Ben Smith, Brie Frame, Joe Cabrera, Jenny Gutbezahl, -

Year 76.2 76.3 76.5 76.6 76.7 76.8 76.9

Year Items Donor 1 Fiske, Eustace, E. 76.1 1 Wilder, Donald, Mrs. 76.2 Gill, Russell, Mrs. 76.3 4 5 Morin, Roland, Rev. 76.4 1 Byam, Edwin, Dr. 76.5 12 Parlee, Ralph, Mrs. 76.6 1 Chelms. Historical Society 76.7 1 Hinckley, William, Mr.& Mrs. 76.8 Day, William, A. 76.9 1 7 Warren, Miriam, Miss 76.10 1 Open Gate Garden Club 76.11 1 Emmons, Henry, Mrs. 76.12 6 Chelms. Historical Comm 76.13 2 MacDougall, Allister, Mr.&Mrs. 76.14 63 River Valley House 76.15 1 Norton, Edward, Mrs. 76.16 Farnum, Harold, Mrs. 76.17 12 5 Lahue, Richard, C. 76.18 Nelson, Herbert 76.19 5 3 Hood, Edward 76.20 18 Tec Art Studios 76.21 1 American Brands, Inc. 76.22 2 Sturtevant, Herbert 76.23 3 Norton, Edward, Mrs. 76.24 2 Cowdkry, Frank, Mrs. 76.25 1 Stewart, George, Mr.& Mrs 76,26 1 Lovering, Priscilla, Miss 76.27 1 Foster, Ida, Lovering 76.28 1 Fogg, Donald, Mrs. 76.29 5 Watt, Charles, Mr.& Mrs. 76.30 1 Wilder, Donald, Mrs. 76.31 Scoboria, Marjorie, Miss 76.32 15 3 Shedd, Harry, Jr. 76.33 2 Dana, Leslie, Mrs. 76.34 2 Gullion, Bruce, Mrs. 76.35 4 annonymous 76.36 1 Norton, Edward, Mrs. 76.37 1 National Park Service 76.38 4 Lahue, Richard, O. 76 .39 20 Day, Raymond, A. 76 .40 1 Stevens, Hazel, Miss 76.41 2 Grade 2, Westland School 76 .42 2 Simard, Roland, Mrs. -

Please Click for File Attachment

CITY OF MOBILE BID SHEET This is Not an Order Purchasing Department and Package Delivery: Mailing Address: Government Plaza P. 0. Box 1948 4th Floor, Room S-408 Mobile, Alabama 36633 205 Government St READ TERMS AND CONDITIONS (251) 208-7 434 Mobile, Alabama 36644 ON REVERSE SIDE OF THIS PAGE BEFORE BIDDING lyped by : nm Buyer: 006 Please quote the lowest price at which you will furnish the articles listed below DATE BID NO. DEPARTMENT Commodities to be delivered F.O.B. Mobile to: 07/25/2017 5060 Fire To Be Specified This bid must be received and stamped by the Purchasing office not later than· 10:30 Tm:sdav. Au~>ust 15. 2017 Bid on this form ONLY. Make no changes on this form. Attach UNIT PRICE EXTENSION QUANTITY ARTICLES any additional information required to this form. UNIT Dollars Cents Dollars Cents FIRE SERVICE BUNKER GEAR Appx 0 to Bunker Coat, Mobile Fire Rescue Department Specifications and NFPA 300 Pamphlet 1971,2013 revision. NFPA (FDNY) tri-color reflective trim, nomex radio pocket on left chest, 4" reflective sewn-on lime/yellow letters "MFRD" for back of coat, hanging Jetter patch at rear bottom for firefighter's name, as per the attached specifications. Make___________ Model __________ Appx 0 to Bunker Pants, Mobile Fire Rescue Specifications and NFPA Pamphlet 1971 , 300 2013 revision. NFPA 1971 tri-color reflective trim as per the attached specifications. To be furnished with Padded Ripcord Adjustment "H" Style Suspenders, as per the attached specifications. Make------------ Model----------- Appx 0 to Bunker Pants, with Internal Seat Harness, to be furnished with Padded 60 Ripcord Adjustment "H" Style Suspenders. -

Catalogue 2019

Catalogue 2019 Fidlock - the new generation of fasteners Fidlock was founded with the aim of developing easy-to-use and trend-setting magnetic-mechanical fasteners in an appealing design that revolutio- nise even long-established concepts. Our innovative fastener concepts based on the Fidlock concept offer users a new dimension in terms of functi- onality, safety and fun. The great ease of use, ergonomic features as well as classy and robust processing convince users straightaway. In daily use, Fidlock fasteners offer qualities that have never been achieved before: they close automatically and can be opened comfortably with one hand - even when wearing gloves. Users especially appreciate this advantage for sporting activities; it means that they can use their other hand to ensure their own safety. All Fidlock fasteners combine a high level of reliability with the simplest method of opening and closing a fastener. At present, Fidlock offers product developers and designers a large range of innovative magnetic fasteners in eleven product families. This means that they get the right solution for a wide range of application areas and individual design concepts. Thanks to the large selection of different designs and materials as well as opportunities for individualisation, product designers do not have to make any compromises with Fidlock fasteners. Our fastener concepts are not only based on multiple award-winning, unique technology, they also complement and refine our customers‘ products with convincing quality features. In this way, innovative product lines or extra added value is created for our customers. Users are thrilled with the intuitive one-hand-operation, design and secure hold of the Fidlock fasteners - no matter whether they are used on top-quality pieces of furniture, bags, ruck- sacks, helmet or other sport and lifestyle brand items: our fasteners stand for the greatest ease of use, security, fun and function.