State-Funded Dual Enrollment Program: One State’S Personalization Approach to Increase High School Graduation Rates and Reduce Dropout Rates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2012

TOWN OF DORSET SIDEBAR TITLE Annual Report 2012 Floor Meeting ~ Dorset School ~ Monday, March 4, 2012 ~ 7:00 p.m. Voting ~ Dorset School ~ Tuesday, March 5, 2012 ~ 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. 2012 Dorset Town Report Dedication Malcolm Cooper & Alan Calfee: Malcolm Cooper Jr. was born in Pittsfield, MA in 1949. Soon after, the Cooper family moved to Dorset. Malcolm attended The Dorset Village School , Burr & Burton, Kim- ball Union Academy, & the University of Denver. After college he stayed out west working as a ski instructor and fire fighter for the Forest Service. Malcolm then returned home to Vermont to become involved in running the fami- ly business: JK Adams. Under Malcolm’s guidance, JK Adams has become a well-known national distributor of fine wood products that can be found in many a kitchen. Dorset is fortunate to have a business like JK Adams as a fixture in our landscape, employing many residents and giving back to the community whenever possible. Alan Calfee was born in Washington DC in 1962. Like the Coopers, the Calfee family has been in Dorset for many years. Alan Calfee studied Natural Resource Management at the University of Maryland and received a Master’s Degree in Forestry from UVM. Alan is a well known local forester, his company Calfee Woodland Management is located right here in Dorset. Alan also lovingly oversees large tracts of conserved land owned by his family. Recently Alan has been involved in an effort to conserve the peak of Haystack Mountain in Pawlet. Alan’s commitment to land stewardship and knowledge of land planning has been an invaluable resource to the Dorset Conservation Commission and the greater Dorset community. -

Joanna A. Christodoulou, Edd Dept

Joanna A. Christodoulou, EdD Dept. of Communication Sciences and Disorders MGH Institute of Health Professions 36 1st Avenue Boston, MA 02129-4557 (617) 643-1482 [email protected] Education EdD, Human Development and Psychology, 2010 Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA EdM, Mind, Brain, and Education, 2006 Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA MA, Applied Child Development, 2003 Eliot-Pearson Dept. of Child Development, Tufts University, Medford, MA BS, Biology-Psychology and Biomedical Engineering, 2001 Tufts University, Medford, MA Postdoctoral Training McGovern Institute for Brain Research, 2010-2013 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA Academic Appointments and Affiliations Assistant Professor. MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, MA 2014- Adjunct Lecturer on Education. Harvard Graduate School of Education, 2014- Cambridge, MA Research Affiliate. Speech-Language Pathology Department, 2016- Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA Research Affiliate. McGovern Institute for Brain Research, 2014- Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA MemBer of the Faculty. Harvard Graduate School of Education, 2012-2013 Cambridge, MA Lecturer. Psychology Department, Harvard College, Cambridge, MA. 2012-2013 Adjunct Assistant Professor. MGH Institute of Health Professions, 2010-2013 Boston, MA Instructor. Psychology Department, Harvard College, Cambridge, MA. 2008-2011 Instructor. Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA 2009 Clinical Appointments Oral and Written -

ET 2010 with FINAL FINAL Edits:Layout 1

the ElmTreefor the alumni, friends, and parents of Lawrence Academy Spring 2010 First Word Brewing Success on Cape Cod In reading the featured by Andrew J. Brescia, director of communications profiles in this issue of The Elm Tree, I take In reflecting upon his education, Todd Marcus ’85, who exceptional pride in was born in Malden and grew up in Ashland, says that he knowing that each could in- has learned most from the School of Hard Knocks. As clude the following with most clichés, however, this observation falls subheading: “Demonstrating desperately short in accounting for the adventures that once again that the mission have shaped him into the successful entrepreneur he is of Lawrence Academy today as the owner and operator of Cape Cod Beer. continues to come alive in For example, he did not learn in any classroom about the the pursuits of our students Head of School D. Scott Wiggins derivation of “porter” as it is used in naming a beer. At a and our graduates!” moment’s notice, however, Todd, like a soft-spoken Guided by its mission, Lawrence Academy seeks to imbue docent, explains matter-of-factly that a dark, chocolaty its students with the creativity and passion necessary to brew was originally the drink of the common man of define their own goals and the resourcefulness and East London, dockworkers who were called porters. You discipline necessary to achieve those goals. The first 20 can learn about Prohibition in U.S. History class, but, words of Lawrence Academy’s mission statement capture odds are, not about the recipe for “small beer”—written succinctly what the entrepreneurs—social and economic in a diary in 1754 by George Washington—that now —whose achievements are chronicled in this Elm Tree are resides at the New York Public Library. -

Christopher G. Bakriges, Ph.D

Christopher G. Bakriges, Ph.D. www.bakriges.com Areas of Concentration Ethnomusicology: World Music; Ethnography (analysis, field/lab methods, area studies) Jazz: Improvisation, Theory, Arranging, History, Ensemble, Performance, Piano, MIDI Popular Music Studies: American and non-Western Music; Global Pop; Modernism; Avant-gardism Professional Qualifications/Teaching History 2013-present, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 621 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 Visiting Lecturer, Liberal Arts Department, teaching The World of Music; supervise directed study in music theory and composition; 2013, MassArt, Studio for Interrelated Media, Multimedia & Performing Arts Dept., Boston, MA Artist in Residence; conduct workshops in musicianship and theory for Projects in Sound, Choreography and Performance, Recording Arts Studio courses, and an Art History independent study 2003-present, Elms College, 291 Springfield Street, Chicopee, MA 01013 Lecturer, Humanities and Fine Arts and Creative Artist in Residence; coordinate music minor curriculum; teach classes; conduct ensembles; stage recitals; departmental and divisional initiatives; music director, Elms Theater for Social Justice 2014-present, Elms College Partnership, Berkshire Medical Center, Pittsfield, MA [summer] *Lecturer, RN/BS Nursing Program; teach Music Cultures of the World, Berkshire Campus (‘17) *Lecturer, Performing Arts Department, Holyoke Community College, Holyoke, MA; teach The World of Music in the accelerated bachelor's degree program for students in accounting -

Alumni at Large

Colby Magazine Volume 91 Issue 2 Spring 2002 Article 11 April 2002 Alumni at Large Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine Recommended Citation (2002) "Alumni at Large," Colby Magazine: Vol. 91 : Iss. 2 , Article 11. Available at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/colbymagazine/vol91/iss2/11 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Magazine by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. '20s/'30s-l 940s Alumni at Large for his repair-. At present we are 1940s Correspondents •l·Mh• having "his and hers" chemotherapy 1940 Bibby Levine Alfond '38 and her husband, for c:i nccr. ow that's real togeth T 1 Ernest C. Marriner Jr. larold 11'80, recently offered a $500,000 ncss1 There's plenty of 111ileage left in 10 Wa lnut Drive matching challenge grant to the i\laine our rusty bodies, mid we hope soon to 1 Augusta, ME 04330-6032 Children's lome for Little \ Va nderers, a be on the road ro recovery to celcbra re 207-623-0543 non prof-it <lgency in \ Vatcrville th<lt provides our 58th wedding annivers:iry in [email protected] adoption and fo ster care a well as many i\ larch. See you all at the 2002 Colby other services and programs for childre1;. Reunion \ Vc ekend in .June." 1941 She W<lS a bo:ird member of the home for 12 -f:mest C. 1\ /11rri11er]1: Bonnie Roberts Hatl1away ye;irs and has served <lS <ln honornry board 400 Atlantic Ave nue #34C member since l 980. -

Arlington Memorial High School Student-Athlete Named Gatorade Vermont Girls Soccer Player of the Year

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [email protected] ARLINGTON MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT-ATHLETE NAMED GATORADE VERMONT GIRLS SOCCER PLAYER OF THE YEAR CHICAGO (June 13, 2019) — In its 34th year of honoring the nation’s best high school athletes, The Gatorade Company today announced Tess Belnap of Arlington Memorial High School as its 2018-19 Gatorade Vermont Girls Soccer Player of the Year. Belnap is the first Gatorade Vermont Girls Soccer Player of the Year to be chosen from Arlington Memorial High School. The award, which recognizes not only outstanding athletic excellence, but also high standards of academic achievement and exemplary character demonstrated on and off the field, distinguishes Belnap as Vermont’s best high school girls soccer player. Now a finalist for the prestigious Gatorade National Girls Soccer Player of the Year award to be announced in June, Belnap joins an elite alumni association of past state soccer award-winners, including Alexi Lalas (1987-88, Cranbrook High School, Mich.), Steve Cherundolo (1996-97, Mt. Carmel High School, Calif.), Abby Wambach (1997-98, Our Lady of Mercy School for Young Women, N.Y.), Heather O’Reilly (2001-02, 2002-03, East Brunswick High School, N.J.), Matt Besler (2004-05, Blue Valley West High School, Kans.), Jack Harrison (2013-14, Berkshire High School, Mass.) and Mallory Pugh (2014-15, Mountain Vista High School, Colo.). The 5-foot-5 senior midfielder scored 37 goals and passed for 14 assists this past season, leading the Eagles (17-1) to the Division 4 state championship. A United Soccer Coaches All-American, Belnap is a four-time All-Conference selection and twice earned First Team All-State honors from the Burlington Free Press. -

Concurrent Resolution Addendum

CONCURRENT RESOLUTION ADDENDUM TO THE HOUSE CALENDAR Text of House Concurrent Resolutions of April 19, 2018 Concurrent Resolutions for Adoption Under Joint Rule 16 The following concurrent resolutions will be adopted automatically unless a Representative or Senator requests floor consideration before the end of Friday’s legislative session. Requests for floor consideration must be communicated to the House Clerk’s office or the Senate Secretary’s office. Resolutions H.C.R. 328. House concurrent resolution congratulating the 2017 Rivendell Academy Raptors Division IV championship boys’ soccer team Offered by: Representative Copeland-Hanzas of Bradford Offered by: Senators Benning, Kitchel, and MacDonald Whereas, until the momentous 2017 season, the Rivendell Academy boys’ soccer team had never stepped onto a championship field, and Whereas, the Raptors were seeded first for the Division IV playoffs, a great accomplishment and a symbolic step toward earning the long-elusive championship crown, and Whereas, Rivendell proved its top ranking was merited, securing a berth in the decisive game in Randolph, where the second-seeded Long Trail School Mountain Lions team was the formidable opponent, and Whereas, Rivendell’s fans excitedly cheered the Raptors before the game began, thrilled to have reached this new competition plateau, and Whereas, the Raptors did not disappoint their supporters, scoring the sole goal 12 minutes into the game, and Rivendell’s resilient defense continuously rebuffed the Mountain Lions, who hovered near the goal post -

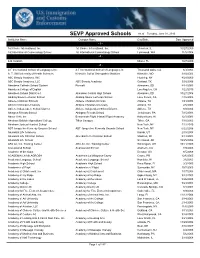

SEVP Approved Schools As of Tuesday, June 01, 2010 Institution Name Campus Name City/State Date Approved - 1

SEVP Approved Schools As of Tuesday, June 01, 2010 Institution Name Campus Name City/State Date Approved - 1 - 1st Choice International, Inc. 1st Choice International, Inc. Glenview, IL 10/27/2009 1st International Cosmetology School 1st International Cosmetology School Lynnwood, WA 11/5/2004 - 4 - 424 Aviation Miami, FL 10/7/2009 - A - A F International School of Languages Inc. A F International School of Languages In Thousand Oaks, CA 6/3/2003 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Kirksville Coll of Osteopathic Medicine Kirksville, MO 3/10/2003 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. Flushing, NY 4/28/2009 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC ABC Beauty Academy Garland, TX 3/30/2006 Aberdeen Catholic School System Roncalli Aberdeen, SD 8/14/2003 Aberdeen College of English Los Angeles, CA 1/22/2010 Aberdeen School District 6-1 Aberdeen Central High School Aberdeen, SD 10/27/2004 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Abiding Savior Lutheran School Lake Forest, CA 4/16/2003 Abilene Christian Schools Abilene Christian Schools Abilene, TX 1/31/2003 Abilene Christian University Abilene Christian University Abilene, TX 2/5/2003 Abilene Independent School District Abilene Independent School District Abilene, TX 8/8/2004 Abington Friends School Abington Friends School Jenkintown, PA 7/15/2003 Above It All, Inc Benchmark Flight /Hawaii Flight Academy Kailua-Kona, HI 12/3/2003 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Tifton Campus Tifton, GA 1/10/2003 Abraham Joshua Heschel School New York, NY 1/22/2010 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School New York, NY 6/22/2006 Abundant Life Academy Kanab, UT 2/15/2008 Abundant Life Christian School Abundant Life Christian School Madison, WI 9/14/2004 Abundant Life School Sherwood, AR 10/25/2006 ABX Air, Inc. -

Coaching Staff Head Coach Matt Paton

A staple in the New York region and an emerging program on the national stage, the Manhattanville College Athletic Department continues to bolster its reputation as a program on the rise in all areas: athletic achievement, academic success and overall participation. More than 325 Valiant student-athletes (nearly 20 percent of the student body) took part in intercollegiate athletics during the 2011-12 school year showcasing the continued and rapid growth of athletics at Manhattanville. With women’s golf beginning play as a varsity sport in 2012-13, the program now sponsors 20 competitive intercollegiate teams – including eight teams that have been established or re-established since 2007 alone. And teams at Manhattanville do not just compete, they win. Three teams earned conference regular-season or tournament championships in 2011-12 and two Valiant squads (men’s soccer and men’s golf) made an appearance in the NCAA Tournament. Fifteen of 21 Valiant squads earned berths in their respective conference championships last year, including the third straight title and seventh in 11 seasons for men’s golf. In addition, the men’s hockey, men’s golf and women’s hockey teams all received national rankings over the course of the year. On an individual level, many Valiant student-athletes were honored in 2011-12 as well, led by All-America selections Eros Olazabal (men’s soccer) and Dan Fiorito (baseball). Manhattanville also boasted three Freedom Conference Players of the Year and two Freedom Rookies of the Year to go with 47 combined All-Conference honorees. In recent years, at least 35 former Valiants have gone on to play their sport professionally either domestically or overseas as well. -

JOANNA A. CHRISTODOULOU EMAIL: [email protected] OFFICE PHONE: 1.617.643.1482 EDUCATION Ed.D

JOANNA A. CHRISTODOULOU EMAIL: [email protected] OFFICE PHONE: 1.617.643.1482 EDUCATION Ed.D. Harvard Graduate School of Education, Human Development and Psychology Ed.M. Harvard Graduate School of Education, Mind, Brain, and Education M.A. Tufts University, Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Development B.S. Tufts University, Biology-Psychology and Biomedical Engineering ACADEMIC POSITIONS Assistant Professor, Dept. of Communication Sciences and Disorders, MGH Institute of Health Professions, 2013- Post-Doctoral Associate, Gabrieli Lab, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, MIT, 2010-2013 Lecturer, Psychology Department, Harvard College, 2012-2013 Adjunct Assistant Professor, MGH Institute of Health Professions, 2010-2013 Instructor, Psychology Department, Harvard College, 2008-2011 Researcher, Gabrieli Lab, MIT, 2005-2010 Instructor, Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE), 2009 Researcher, Strategic Education Research Partnership (SERP), 2006-2009 Researcher, Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST), 2005 Fulbright Fellow, Athens, Greece, 2003-2004 Researcher, Center for Reading and Language Research, Tufts University, 1998-2003 SELECTED AWARDS AND HONORS Scholarship Awards The Peter and Elizabeth C. Tower Foundation, Co-Principal Investigator, 2013-2014 National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2013-2015 George E. Burch Fellowship, Smithsonian Institution, Principal Investigator, 2012-2014 William F. Milton Fund, Harvard Medical School, Co-Principal Investigator with -

(802) 440-4466 E-Mail: [email protected] Website

CURRICULUM VITAE Elizabeth Sherman OFFICE ADDRESS: Natural Science Bennington College Bennington, VT 05201 (802) 440-4466 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://faculty.bennington.edu/~sherman/ EDUCATION: Ph.D., Zoology, High Distinction, University of Vermont, 1977 Neurobiology & Behavior, Cornell University, 1972-73 Summer Marine Biology Program, Cornell University, 1971 On research station on Isles of Shoals, NH and ME. B.A., Biology, High Distinction, University of Rochester, 1972 PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT: Visiting Scientist, Department of Environment, Cayman Islands Sabbatical leave 2010; summers & FWT-present Professor of Biology, Bennington College, 1978-present Scientist-in-residence, Long Trail School, private high school in Dorset, VT Supported in part by grant from NSF (sabbatical, 1995-1996) Curriculum Coordinator (Chair), Bennington College, Natural Science & Mathematics, 1984-1986; 1992-1994; 2003-2005 Postdoctoral Fellow, Cornell University, 1977-78 Neurobiology & Behavior National Science Foundation Graduate Fellow, 1974-1977 Department of Zoology, University of Vermont Graduate Teaching Fellow, University of Vermont, 1973-74 Department of Zoology Graduate Teaching Assistant, Cornell University, 1972-73 Undergraduate Teaching Fellow, University of Rochester, 1971 Department of Biology AWARDS/GRANTS/FELLOWSHIPS: Math Science Partnerships Grant, Instructor. Grant awarded to Math and Science Partnership of the Southwest Vermont Curriculum Coordinators' Collaborative (SWVTCC), 2009-2014. Problems in amphibian diversity: has pH served as a selective agent in the evolution of newts. Grant from American Wildlife Research Foundation, Inc. 2001 Developmental differences among newts (Notophthalmus viridescens) as a function of pond pH. Grant from American Wildlife Research Foundation, Inc. 2000 Integrating Science & Math in the Classroom V: Biodiversity: Organisms, Evolution, and Interdependence. Funded through National Science Foundation, Vermont Institute for Science, Math, & Technology. -

U.S. DEPARTMENT of HOMELAND SECURITY July 29, 2003 ICE

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY BUREAU OF IMMIGRATION AND CUSTOMS ENFORCEMENT (ICE) July 29, 2003 ICE PREPARES U.S. SCHOOLS AND FOREIGN STUDENTS FOR AUGUST 1, 2003 SEVIS DEADLINE New steps to help legitimate foreign students while preserving security WASHINGTON, DC— The Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) today announced that it is taking new steps to help law-abiding foreign students, as well as U.S. educational institutions, comply with the August 1, 2003 filing deadline for the Student Exchange Visitor and Information System (SEVIS). SEVIS is a government, computerized system that maintains and manages data about foreign students and exchange visitors during their stay in this country. For more than 50 years, U.S. educational institutions have been required to maintain such information about foreign students studying at their facilities. In the past, this was a decentralized, inefficient, and paper-driven system. SEVIS, for the first time, automates and centralizes this system. SEVIS allows for real-time access to this information and helps students comply with the terms of their visas. Congress mandated that August 1, 2003 be the deadline for U.S. educational institutions with a foreign student population to be certified participants in SEVIS and have information about these current foreign students entered into SEVIS. To date, 5,937 U.S. schools have complied with this deadline and become SEVIS-certified, enabling them to accept foreign students. ICE applauds these schools for meeting this deadline. However, there are still more than 600 U.S. schools that have yet to file applications, or have filed applications late in the process and therefore may not meet the deadline.