Partition Stories: Epic Fragments and Revenge Tragedies (A Review Article)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rajinder Singh Bedi (Bio for Centennial Celebrations)

© Nischint Bhatnagar Rajinder Singh Bedi (Bio for Centennial celebrations) Born September 01, 1915 at Lahore Cantonment, Sadar Bazaar; Died November 11, 1984 in Bombay. His father, S. Hira Singh Bedi was a Postmaster. He was very fond of Urdu and Farsi. His Mother Smt. Sewa Dei was from a Hindu family and very knowledgeable of Sikh and Hindu religion, the stories of the Puranas and also of Muslim lore. She was a wonderful painter and had covered the walls of the house with scenes from the Mahabharata. The house had a mixed culture of Sikhism and Hinduism and father took part in Muslim festivals enthusiastically. Rajinder’s imaginative skills were developed under their fond care, storytelling and father’s witticisms. He matriculated from the S.B.B.S. Khalsa High School, Lahore and joined the DAV College, Lahore. He passed his Intermediate but could not go for BA studies. Mother had died March 28, 1933 of tuberculosis and father wanted him to marry so that there may be a caregiver in the family. He left his studies and joined the postal service as a clerk in 1933. He got married in 1934. His wife’s maiden name was Soman and married name Satwant Kaur. His first son, Prem, was born in 1935. Father who was then working as Postmaster in Toba Tek Singh came to Lahore to celebrate the arrival of a grandson but died there on August 31, 1935. The whole burden for fending for his family, his two brothers and sister fell on him and Satwant. The son Prem also passed away in 1936. -

Gurpurab Greetings

www.punjabadvanceonline.com Gurpurab Greetings Sri Guru Nanak Dev's 550th birth anniversary (Nov 23) 2 Punjab Advance August 2016 Editorial The Boy Who Cried Wolf is one of my favourite Aesop's Fables, I don’t know why but it appears to fit into the current Delhi smog tale. For the third year running Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal repeated his ‘stubble burning’ cries. His hat-trick of alarm calls remind me of the shepherd boy who cried wolf, with no wolf around. Initially the people came to his aid, but when he repeated the cries no one turned up and ultimately he fell vic - tim to his own follies. The Punjab Chief Minister Capt Amarinder Singh has been quick in ridi - culing the nonsensical claim of his Delhi counterpart asking him to stop in - dulging in political theatrics and to check the facts before shooting from the mouth. He has trashed as yet another attempt by the Delhi Chief Min - ister to divert public attention for his own government’s abysmal failure on all counts. As per data provided by private and government agencies stubble burn - ing accounts for a bare 4 per cent of the total smog enveloping the National Capital Region. More than 80 per cent of the deadly cocktail of soot, smoke, metals, nitratres, sulphates is the result of the local activities like vehicu - lar traffic, industrial pollution, construction activity, garbage burning etc. Vehicular pollution alone contributes 40 per cent of the total pollution level. According to the latest data released by the Ministry of Earth Sciences and the Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) crop burning, which lasts for about 15-20 days during this period, contributes just 4 per cent of the total pollution in Delhi-NCR on an average. -

Punjab Medical Council Electoral Rolls Upto 31-01-2018

Punjab Medical Council Electoral Rolls upto 31-01-2018 S.No. Name/ Father Name Qualification Address Date of Registration Validity Registration Number 1. Dr. Yash Pal Bhandari S/o L.M.S.F. 1948 81, Vijay Nagar, Jalandhar 12.04.1948 45 22.10.2018 Sh. Ram Krishan M.B.B.S. 1961 M.D. 1965 2. Dr. Balwant Singh S/o LSMF 1952 1814, Maharaj nagar, Near Gate No.3, 28.10.1952 3266 17.03.2021 Sh. Suhawa Singh M.B.B.S. 1964 of P.A.U., Ludhiana 3. Dr. Kanwal Kishore Arora S/o M.B.B.S. 1952 392, Adarsh Nagar Jalandhar 15.12.1952 3312 09.03.2019 Sh. Lal Chand Pasricha 4. Dr. Gurbax Singh S/o LSMF 1952 B-5/442, Kulam Road, Tehsil 11.03.1953 3396 23.04.2019 Sh. Mangal Singh M.B.B.S. 1956 Nawanshahr Distt. SBS Nagar D.O. 1957 5. Dr. Jawahar Lal Luthra L.S.M.F. 1953 H.No.44, Sector 11-A, Chandigarh 27.10.1953 3555 07.10.2018 M.B.B.S. 1956 M.S. (Ophth.) 1970 6. Dr. Kirpal Kaur M.B.B.S. 1953 490, Basant Avenue, Amritsar 09.12.1953 3599 31.03.2019 M.D. 1959 7. Dr. Harbans Kaur Saini L.S.M.F. 1954 Railway Road, Nawan Shahr Doaba 31.05.55 4092 29.01.2019 8. Dr. Baldev Raj Bhateja L.S.M.F. 1955 Raj Poly Clinic and Nursing Home, Pt. 08-06-1955 4106 09.10.2018 Jai Dayal St., Muktsar. -

Indian Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies

ISSN 2321-8274 Indian Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies Volume 1, Number 1 September, 2013 Editors Mrinmoy Pramanick Md. Intaj Ali Published By IJCLTS is an online open access journal published by Mrinmoy Pramanick Md. Intaj Ali And this journal is available at https://sites.google.com/site/indjournalofclts/home Copy Right: Editors reserve all the rights for further publication. These papers cannot be published further in any form without editors’ written permission. Advisory Committee Prof. Avadhesh Kumar Singh, Director, School of Translation Studies and Training, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi Prof Tutun Mukherjee, Professor, Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh Editor Mrinmoy Pramanick Md. Intaj Ali Co-Editor Rindon Kundu Saswati Saha Nisha Kutty Board of Editors (Board of Editors includes Editors and Co-Editors) -Dr. Ami U Upadhyay, Professor of English, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University, Ahamedabad, India - Dr. Rabindranath Sarma, Associate Professor, Centre for Tribal Folk Lore, Language and Literature, Central University of Jharkhand, India - Dr. Ujjwal Jana, Assistant Professor of English and Comparative Literature, Pondicherry University, India - Dr. Sarbojit Biswas, Assitant Professor of English, Borjora College, Bankura, India and Visiting Research Fellow, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia - Dr. Hashik N K, Assistant Professor, Department of Cultural Studies, Tezpur University, India - Dr. K. V. Ragupathi, Assistant Professor, English, Central University of Tamilnadu, India - Dr. Neha Arora, Assistant Professor of English, Central University of Rajasthan, India - Mr. Amit Soni, Assistant Professor, Department of Tribal Arts, Indira Gandhi National Tribal University, Amarkantak, M.P., India AND Vice-President, Museums Association of India (MAI) - Mr. -

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL

(RJELAL) Research Journal of English Language and Literature Vol.3.Issue 4.2015 A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal (Oct-Dec) http://www.rjelal.com RESEARCH ARTICLE EXPERIMENTS IN FORM AND CONTENT: APPROXIMATING INDIAN PROGRESSIVE WRITING IN CONTEMPORARY LITERARY DISCOURSE GHULAM MOHAMMAD KHAN Research Scholar Department of English and Foreign Languages Central University of Haryana ABSTRACT Given the unprecedented intellectual and critical activity in the field of literary and cultural studies, theorists, creative writers and public intellectuals have grown conscious of the arbitrariness and fluidity of the ideological and epistemological structures at work in the theory industry. The form as well content of modern literary texts come under the influence of these structures or thought processes in one way or the other. In these literary and theoretical complexities, there is a possibility of exploring and re-reading the great oeuvre of Progressive Writings. This paper will study, how certain literary and ideological experiments employed by various Progressive writers are still as relevant as they were in late 1930’s and early 1940’s, when the movement was at its peak. Progressive writers’ departure from the ponderous romantic and imaginative ebullience and formal and lexical intricacies of the nineteenth and early twentieth century poets and fiction writers and embracing a new pattern of both form and content are still very relevant and authentic issues in the field of literary studies. Though this writers’ association disintegrated and finally demised after the Independence, the writers of this association had already invested an unparallel effort to turn literature into a vehicle of social realism. -

Magazine-2-3 Final.Qxd (Page 3)

SUNDAY, JANUARY 31, 2021 (PAGE 3) SACRED SPACE FORBEARANCE helps face difficulties How to be a failure? Akhtar Ul-nisa it to grow strong and pure we need to be regular in our spiritual practices and assert our Ankush Sharma stories", nobody gives a damn to the "failure stories". But it Forbearance is the ability to respond to a independence from the desire in the mind. It needs must not be ignored that the failed people have faced multi- situation of failure, disappointment, pain patience, presence, grace and focus. Failure! Yes, you have read right. This write-up will surf dimensional hurdles in their struggle and are more experi- you through the various paths leading to the failure. It may enced compared to the toppers especially those who got suc- or conflict with understanding and Significance of forbearance seem absurd but believe me, it would make sense in a few cess early. It is not to say that the toppers are not insightful minutes read. In fact, it has something crucial to offer to rather what I mean is that some people have inbuilt brilliance The quality of forbearance is of the highest importance composure. those who are aspiring to achieve success in their lives. or a good schooling background which might not be every- to every human being. Forbearance and nonviolence are It is bearing the physical, mental and emotional pain Success may have different meanings to different people but one's case. So, it's the failed people who can actually eluci- manifestation of inner strength. Reactivity and retaliation with strong and steady faith without lamenting or worry- the paths leading there have a common and a simple princi- date the worst struggle scenarios and impediments allowing make us to lose precious energy, forbearance on the other ing. -

In the Heat of Fratricide: the Literature of India's Partition Burning Freshly (A Review Article)

In the Heat of Fratricide: The Literature of India’s Partition Burning Freshly (A Review Article) India Partitioned: The Other Face of Freedom. Edited by M H. volumes. New Delhi: Lotus, Roli Books, . Orphans of the Storm: Stories on the Partition of India. Edited by S C and K.S. D. New Delhi: UBSPD, . Stories about the Partition of India. Edited by A B. volumes. Delhi: Indus, HarperCollins, . I This is not that long awaited dawn … —Faiz Ahmad Faiz T surrounding the Partition of India on August –, created at least ten million refugees, and resulted in at least one million deaths. This is, perhaps, as much as we can quantify the tragedy. The bounds of the property loss, even if they were known, could not encompass the devastation. The number of persons beaten, maimed, tortured, raped, abducted, exposed to disease and exhaustion, and other- wise physically brutalized remains measureless. The emotional pain of severance from home, family and friendships is by its nature immeasur- able. Fifty years have passed and the Partition remains unrequited in the historical experience of the Subcontinent. This is, in one sense, as it should be, for the truth remains that the Partition unleashed barbarism so cruel, indeed so thorough in its cruelty, and complementary acts of compassion so magnificent—in short a com- • T A U S plex of impulses so pernicious, so heroic, so visceral, so human—that they cannot easily be assimilated into normal life. Neither can they be forgot- ten. And so, ingloriously, the experience of the Partition has been perhaps most clearly assimilated in the perpetuation of communal hostility within both India and Pakistan, for which it serves as the defining moment. -

Book Review Interpreting Cinema: Adaptations, Intertextualities, Art Movements by Jasbir Jain

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Vol. 12, No. 4, July-September, 2020. 1-5 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n4/v12n424.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n4.24 Book Review Interpreting Cinema: Adaptations, Intertextualities, Art Movements by Jasbir Jain Jaipur & Delhi: Rawat Publications, 2020 298 pages; Rs. 1295/- ISBN 9788131611425 Reviewed by Somdatta Mandal Former Professor of English, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, W.B. Email: [email protected] Film studies now has become a full-fledged discipline with several theoretical approaches lined up behind it and has a strong foothold in serious academics. Films are now read from various perspectives as text, as a serious novel is read over and over again, since every successive reading/viewing yields additional insights into their meaning. Interpreting Cinema: Adaptations, Intertextualities, Art Movements by eminent academician and scholar Jasbir Jain is a collection of sixteen essays which explores the academic aspect of film studies and has a wide range of © AesthetixMS 2020. This Open Access article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. For citation use the DOI. For commercial re-use, please contact [email protected]. 2 Rupkatha Journal, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2020 primarily Hindi films for discussion crossing decades, genres and cultures. The essays in this volume take up adaptations from fiction and drama both from within the same culture and across cultures and explore the relationships between cultures and mediums. -

Twentieth-Century Urdu Literature

Published in Handbook of Twentieth-Century Literatures of India, ed. by Nalini Natarajan, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 1996. TWENTIETH-CENTURY URDU LITERATURE1 Omar Qureshi This introductory summary, of the course of Urdu literature in the twentieth century must continuously refer back to the nineteenth. This becomes necessary because, depending on one’s point of view, it was Urdu’s destiny or misfortune to gradually become identified as the lingua franca of the Muslims of India in the latter half of the last century. Consequently, the still unresolved dilemmas of the politics of Muslim identity in South Asia are difficult to separate from their expression in and through the development of Urdu. For our purposes then, the most significant consequence of the failed rebellion of 1857 was the gradual emergence of group identity among the recently politically dispossessed and culturally disoriented Muslim elite of North India. This effort to define Indian Muslim nationhood in the new colonial environment placed issues of past, present and future identity at the center of elite Muslim concerns. Not only were these concerns expressed largely in Urdu, but the literary legacy of Urdu formed the terrain through and on which some of the more significant debates were conducted. The Muslim leadership that emerged after 1857 looked to this pre-colonial literary legacy as an authentic, but highly problematic repository of the Indian Muslim identity; and the Urdu language itself as the most effective medium for the renewal and reform of the Muslims of British India. As Muslim identity politics gathered strength in colonial India, and Urdu was turned into the print language of the emerging nation, discussions of an apparently purely literary nature became a veritable mirror of ideological and sociopolitical change among India’s Muslims. -

(Honours) Examination, April, 2016, PU, Chandigarh Page

Result of the B.Com. Third Year (Honours) Examination, April, 2016, P.U., Chandigarh Page No.: 1 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Roll No. Regd. No. Name of the candidate Subjects Father's / Mother's Name Result -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- D.A.V. College, Abohar 10113000954 Arushi Ahuja Business Finance & Accounting : Manoj Ahuja / Mamta Ahuja 115 10113000955 Bableen Kaur Business Finance & Accounting : Karnail Singh / Karamjeet Kaur 129 10113000956 Bavneet Kaur Business Finance & Accounting : Joginder Singh / Gurpreet Kaur 131 10113000958 Harleen Sidhu Business Finance & Accounting : Sukhpal Singh / Sukhpreet Kaur 119 10113000960 Himani Business Finance & Accounting : Mukand Lal / Sushma Devi 120 10113000962 Jashan Preet Business Finance & Accounting : Partap Singh / Paramjeet Kaur 127 10113000967 Komal Gakhar Business Finance & Accounting : Shanker Lal Gakher / Uma Rani 129 Gakher 10113000976 Nitika Chugh Business Finance & Accounting : Rajinder Kumar Chugh / Anita 123 Chugh 10113000987 Razia Wadhwa Business Finance & Accounting : Ajay Wadhwa / Kavita Wadhwa Cancelled 10113000991 Riya Business Finance & Accounting : Vijay Kumar / Seema Rani 135 10113000992 Riya Wadhwa Business Finance & Accounting -

Evaluative Report of Premchand Archives & Literary Center

EVALUATIVE REPORT OF PREMCHAND ARCHIVES & LITERARY CENTER 1. Name of the Department: Jamia’s Premchand Archives & Literary Centre 2. Year of establishment: July, 2004 3. Is the part of a Centre of the University? Yes 4. Names of Programmes offered (UG, PG, M. Phil., Ph. D., Integrated Masters; Integrated Ph.D., D. Sc., D Litt etc.) Supports Research and Study in the field of Humanities, Education and Sociology. It is an Academic Non-Teaching Centre for Research and Reference only 5. Interdisciplinary Programs and Departments involved: Department of English, Department of Hindi, Department of Fine Arts, AJ Kidwai Mass communication Research Centre, 6. Courses in collaboration with other universities, industries, foreign institutions, etc. : Undertakes orientation of participants from National Archives of India 7. Details of programmes discontinued, if any, with reasons NA 8. Examination System: Annual/ Semester/Trimester /Choice Based Credit System NA 9. Participation of the Department in the courses offered by other Departments NA 10. Number of teaching posts sanctioned, filled and actual (Professors/Associate Professors/Asst. Professors/others) S. No. Post Sanctioned Filled Actual (Including CAS & MPS ) 1 Director / Professor one one 1 NON- TEACHING 2 Associate Professors 0 0 0 3 Asst. Professors 0 0 0 11. Faculty profile with name, qualification, designation, area of specialization, experience and research under guidance ACADEMIC NON-TEACHING STAFF 12. List of senior Visiting Fellows, adjunct faculty, emeritus professors etc. NA S. No. Name Qualifi Designation Specializatio No. of No. of Ph.D./M Phil cation n Years of M. Tech / M D Experience students guided for the last four years Awarded In progress 1. -

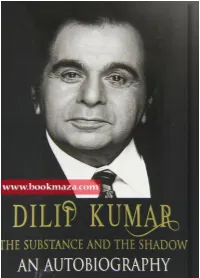

Dilip-Kumar-The-Substance-And-The

No book on Hindi cinema has ever been as keenly anticipated as this one …. With many a delightful nugget, The Substance and the Shadow presents a wide-ranging narrative across of plenty of ground … is a gold mine of information. – Saibal Chatterjee, Tehelka The voice that comes through in this intriguingly titled autobiography is measured, evidently calibrated and impossibly calm… – Madhu Jain, India Today Candid and politically correct in equal measure … – Mint, New Delhi An outstanding book on Dilip and his films … – Free Press Journal, Mumbai Hay House Publishers (India) Pvt. Ltd. Muskaan Complex, Plot No.3, B-2 Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110 070, India Hay House Inc., PO Box 5100, Carlsbad, CA 92018-5100, USA Hay House UK, Ltd., Astley House, 33 Notting Hill Gate, London W11 3JQ, UK Hay House Australia Pty Ltd., 18/36 Ralph St., Alexandria NSW 2015, Australia Hay House SA (Pty) Ltd., PO Box 990, Witkoppen 2068, South Africa Hay House Publishing, Ltd., 17/F, One Hysan Ave., Causeway Bay, Hong Kong Raincoast, 9050 Shaughnessy St., Vancouver, BC V6P 6E5, Canada Email: [email protected] www.hayhouse.co.in Copyright © Dilip Kumar 2014 First reprint 2014 Second reprint 2014 The moral right of the author has been asserted. The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. All photographs used are from the author’s personal collection. All rights reserved.