1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

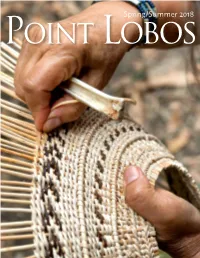

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay Watch the segment online at http://education.savingthebay.org/cultivating-an-abundant-san-francisco-bay Watch the segment on DVD: Episode 1, 17:35-22:39 Video length: 5 minutes 20 seconds SUBJECT/S VIDEO OVERVIEW Science The early human inhabitants of the San Francisco Bay Area, the Ohlone and the Coast Miwok, cultivated an abundant environment. History In this segment you’ll learn: GRADE LEVELS about shellmounds and other ways in which California Indians affected the landscape. 4–5 how the native people actually cultivated the land. ways in which tribal members are currently working to restore their lost culture. Native people of San Francisco Bay in a boat made of CA CONTENT tule reeds off Angel Island c. 1816. This illustration is by Louis Choris, a French artist on a Russian scientific STANDARDS expedition to San Francisco Bay. (The Bancroft Library) Grade 4 TOPIC BACKGROUND History–Social Science 4.2.1. Discuss the major Native Americans have lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. nations of California Indians, Shellmounds—constructed from shells, bone, soil, and artifacts—have been found in including their geographic distribution, economic numerous locations across the Bay Area. Certain shellmounds date back 2,000 years activities, legends, and and more. Many of the shellmounds were also burial sites and may have been used for religious beliefs; and describe ceremonial purposes. Due to the fact that most of the shellmounds were abandoned how they depended on, centuries before the arrival of the Spanish to California, it is unknown whether they are adapted to, and modified the physical environment by related to the California Indians who lived in the Bay Area at that time—the Ohlone and cultivation of land and use of the Coast Miwok. -

An Overview of Ohlone Culture by Robert Cartier

An Overview of Ohlone Culture By Robert Cartier In the 16th century, (prior to the arrival of the Spaniards), over 10,000 Indians lived in the central California coastal areas between Big Sur and the Golden Gate of San Francisco Bay. This group of Indians consisted of approximately forty different tribelets ranging in size from 100–250 members, and was scattered throughout the various ecological regions of the greater Bay Area (Kroeber, 1953). They did not consider themselves to be a part of a larger tribe, as did well- known Native American groups such as the Hopi, Navaho, or Cheyenne, but instead functioned independently of one another. Each group had a separate, distinctive name and its own leader, territory, and customs. Some tribelets were affiliated with neighbors, but only through common boundaries, inter-tribal marriage, trade, and general linguistic affinities. (Margolin, 1978). When the Spaniards and other explorers arrived, they were amazed at the variety and diversity of the tribes and languages that covered such a small area. In an attempt to classify these Indians into a large, encompassing group, they referred to the Bay Area Indians as "Costenos," meaning "coastal people." The name eventually changed to "Coastanoan" (Margolin, 1978). The Native American Indians of this area were referred to by this name for hundreds of years until descendants chose to call themselves Ohlones (origination uncertain). Utilizing hunting and gathering technology, the Ohlone relied on the relatively substantial supply of natural plant and animal life in the local environment. With the exception of the dog, we know of no plants or animals domesticated by the Ohlone. -

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California This chapter discusses the native language spoken at Spanish contact by people who eventually moved to missions within Costanoan language family territories. No area in North America was more crowded with distinct languages and language families than central California at the time of Spanish contact. In the chapter we will examine the information that leads scholars to conclude the following key points: The local tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula spoke San Francisco Bay Costanoan, the native language of the central and southern San Francisco Bay Area and adjacent coastal and mountain areas. San Francisco Bay Costanoan is one of six languages of the Costanoan language family, along with Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chalon. The Costanoan language family is itself a branch of the Utian language family, of which Miwokan is the only other branch. The Miwokan languages are Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Sierra Miwok, Central Sierra Miwok, and Southern Sierra Miwok. Other languages spoken by native people who moved to Franciscan missions within Costanoan language family territories were Patwin (a Wintuan Family language), Delta and Northern Valley Yokuts (Yokutsan family languages), Esselen (a language isolate) and Wappo (a Yukian family language). Below, we will first present a history of the study of the native languages within our maximal study area, with emphasis on the Costanoan languages. In succeeding sections, we will talk about the degree to which Costanoan language variation is clinal or abrupt, the amount of difference among dialects necessary to call them different languages, and the relationship of the Costanoan languages to the Miwokan languages within the Utian Family. -

Ethnohistory and Ethnogeography of the Coast Miwok and Their Neighbors, 1783-1840

ETHNOHISTORY AND ETHNOGEOGRAPHY OF THE COAST MIWOK AND THEIR NEIGHBORS, 1783-1840 by Randall Milliken Technical Paper presented to: National Park Service, Golden Gate NRA Cultural Resources and Museum Management Division Building 101, Fort Mason San Francisco, California Prepared by: Archaeological/Historical Consultants 609 Aileen Street Oakland, California 94609 June 2009 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY This report documents the locations of Spanish-contact period Coast Miwok regional and local communities in lands of present Marin and Sonoma counties, California. Furthermore, it documents previously unavailable information about those Coast Miwok communities as they struggled to survive and reform themselves within the context of the Franciscan missions between 1783 and 1840. Supplementary information is provided about neighboring Southern Pomo-speaking communities to the north during the same time period. The staff of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA) commissioned this study of the early native people of the Marin Peninsula upon recommendation from the report’s author. He had found that he was amassing a large amount of new information about the early Coast Miwoks at Mission Dolores in San Francisco while he was conducting a GGNRA-funded study of the Ramaytush Ohlone-speaking peoples of the San Francisco Peninsula. The original scope of work for this study called for the analysis and synthesis of sources identifying the Coast Miwok tribal communities that inhabited GGNRA parklands in Marin County prior to Spanish colonization. In addition, it asked for the documentation of cultural ties between those earlier native people and the members of the present-day community of Coast Miwok. The geographic area studied here reaches far to the north of GGNRA lands on the Marin Peninsula to encompass all lands inhabited by Coast Miwoks, as well as lands inhabited by Pomos who intermarried with them at Mission San Rafael. -

Chapter 10. Today's Ohlone/ Costanoans, 1928-2008

Chapter 10. Today’s Ohlone/ Costanoans, 1928-2008 In 1928 three main Ohlone/Costanoan communities survived, those of Mission San Jose, Mission San Juan Bautista, and Mission Carmel. They had neither land nor federal treaty-based recognition. The 1930s, 1940s and 1950s were decades when descrimination against them and all California Indians continued to prevail. Nevertheless, the Ohlone/Costanoan communities survived and have renewed themselves. The 1960s and 1970s stand as transitional decades, when Ohlone/ Costanoans began to influence public policy in local areas. By the 1980s Ohlone/Costanoans were founding political groups and moving forward to preserve and renew their cultural heritage. By 1995 Albert Galvan, Mission San Jose descendent, could enunciate a strong positive vision of the future: I see my people, like the Phoenix, rising from the ashes—to take our rightful place in today’s society—back from extinction (Albert Galvan, personal communication to Bev Ortiz, 1995). Galvan’s statement stands in contrast to the 1850 vision of Pedro Alcantara, San Francisco native and ex-Mission Dolores descendant who was quoted as saying, “I am all that is left of my people. I am alone” (cited in Chapter 8). In this chapter we weave together personal themes, cultural themes, and political themes from the points of view of Ohlone/Costanoans and from the public record to elucidate the movement from survival to renewal that marks recent Ohlone/Costanoan history. RESPONSE TO DISCRIMINATION, 1900S-1950S Ohlone/Costanoans responded to the discrimination that existed during the first half of the twentieth century in several ways—(a) by ignoring it, (b) by keeping a low profile, (c) by passing as members of other ethnic groups, and/or (d) by creating familial and community support networks. -

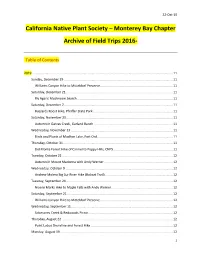

Monterey Bay Chapter Archive of Field Trips 2016

22-Oct-19 California Native Plant Society – Monterey Bay Chapter Archive of Field Trips 2016- Table of Contents 2019 ............................................................................................................................................................ 11 Sunday, December 29 ......................................................................................................................... 11 Williams Canyon Hike to Mitteldorf Preserve................................................................................. 11 Saturday, December 21....................................................................................................................... 11 Fly Agaric Mushroom Search .......................................................................................................... 11 Saturday, December 7......................................................................................................................... 11 Buzzards Roost Hike, Pfeiffer State Park ......................................................................................... 11 Saturday, November 23 ...................................................................................................................... 11 Autumn in Garzas Creek, Garland Ranch ........................................................................................ 11 Wednesday, November 13 ................................................................................................................. 11 Birds and Plants of Mudhen Lake, Fort -

Monterey County

Steelhead/rainbow trout resources of Monterey County Salinas River The Salinas River consists of more than 75 stream miles and drains a watershed of about 4,780 square miles. The river flows northwest from headwaters on the north side of Garcia Mountain to its mouth near the town of Marina. A stone and concrete dam is located about 8.5 miles downstream from the Salinas Dam. It is approximately 14 feet high and is considered a total passage barrier (Hill pers. comm.). The dam forming Santa Margarita Lake is located at stream mile 154 and was constructed in 1941. The Salinas Dam is operated under an agreement requiring that a “live stream” be maintained in the Salinas River from the dam continuously to the confluence of the Salinas and Nacimiento rivers. When a “live stream” cannot be maintained, operators are to release the amount of the reservoir inflow. At times, there is insufficient inflow to ensure a “live stream” to the Nacimiento River (Biskner and Gallagher 1995). In addition, two of the three largest tributaries of the Salinas River have large water storage projects. Releases are made from both the San Antonio and Nacimiento reservoirs that contribute to flows in the Salinas River. Operations are described in an appendix to a 2001 EIR: “ During periods when…natural flow in the Salinas River reaches the north end of the valley, releases are cut back to minimum levels to maximize storage. Minimum releases of 25 cfs are required by agreement with CDFG and flows generally range from 25-25[sic] cfs during the minimum release phase of operations. -

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan DRAFT FOR REVIEW ONLY June 2020 Prepared by: Beyond Green Travel Table of Contents Acknowledgements............................................................................................. 3 Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 5 About Beyond Green Travel ................................................................................ 9 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 10 Vision and Methodology ................................................................................... 16 History of Tourism in Big Sur ............................................................................. 18 Big Sur Plans: A Legacy to Build On ................................................................... 25 Big Sur Stakeholder Concerns and Survey Results .............................................. 37 The Path Forward: DSP Recommendations ....................................................... 46 Funding the Recommendations ........................................................................ 48 Highway 1 Visitor Traffic Management .............................................................. 56 Rethinking the Big Sur Visitor Attraction Experience ......................................... 59 Where are the Restrooms? -

An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Government Documents and Publications First Nations Era 3-10-2017 2005 – An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_ind_1 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation "2005 – An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumas Communities – 1769 to 1810" (2017). Government Documents and Publications. 4. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_ind_1/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the First Nations Era at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Government Documents and Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumash Communities – 1769 to 1810 By: Randall Milliken and John R. Johnson March 2005 FAR WESTERN ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCH GROUP, INC. 2727 Del Rio Place, Suite A, Davis, California, 95616 http://www.farwestern.com 530-756-3941 Prepared for Caltrans Contract No. 06A0148 & 06A0391 For individuals with sensory disabilities this document is available in alternate formats. Please call or write to: Gale Chew-Yep 2015 E. Shields, Suite 100 Fresno, CA 93726 (559) 243-3464 Voice CA Relay Service TTY number 1-800-735-2929 An Ethnogeography of Salinan and Northern Chumash Communities – 1769 to 1810 By: Randall Milliken Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc. and John R. Johnson Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Submitted by: Far Western Anthropological Research Group, Inc. 2727 Del Rio Place, Davis, California, 95616 Submitted to: Valerie Levulett Environmental Branch California Department of Transportation, District 5 50 Higuera Street, San Luis Obispo, California 93401 Contract No. -

Biological Resources of the Del Monte Forest Special-Status Species

BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES OF THE DEL MONTE FOREST SPECIAL-STATUS SPECIES DEL MONTE FOREST PRESERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT PLAN Prepared for: Pebble Beach Company Post Office Box 1767 Pebble Beach, California 93953-1767 Contact: Mark Stilwell (831) 625-8497 Prepared by: Zander Associates 150 Ford Way, Suite 101 Novato, California 94945 Contact: Michael Zander (415) 897-8781 Zander Associates TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Plates 1.0 Introduction................................................................................................................1 2.0 Overview of Special-Status Species in the DMF Planning Area...............................2 2.1 Species Occurrences...............................................................................................2 2.2 Special-Status Species Conservation Planning ......................................................2 2.3 Special-Status Species as ESHA ............................................................................7 3.0 Special-Status Plant Species ......................................................................................9 3.1 Hickman's Onion ....................................................................................................9 3.2 Hooker's Manzanita..............................................................................................10 3.3 Sandmat Manzanita ..............................................................................................10 3.4 Monterey Ceanothus.............................................................................................10