Stringing and Tuning the Renaissance Four-Course Guitar: Interpreting the Primary Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digibooklet Co'l Dolche Suono

Co‘l dolce suono Ulrike Hofbauer ensemble arcimboldo | Thilo Hirsch JACQUES ARCADELT (~1507-1568) | ANTON FRANCESCO DONI (1513-1574) Il bianco e dolce cigno 2:35 Anton Francesco Doni, Dialogo della musica, Venedig 1544 Text: Cavalier Cassola, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch FRANCESCO DE LAYOLLE (1492-~1540) Lasciar’ il velo 3:04 Giovanni Camillo Maffei, Delle lettere, [...], Neapel 1562 Text: Francesco Petrarca, Diminutionen: G. C. Maffei 1562 ADRIANO WILLAERT (~1490-1562) Amor mi fa morire 3:06 Il secondo Libro de Madrigali di Verdelotto, Venedig 1537 Text: Bonifacio Dragonetti, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI (1492-~1565) Recercar Primo 0:52 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda pur della Prattica di Sonare il Violone d’Arco da Tasti, Venedig 1543 Recerchar quarto 1:15 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Regola che insegna sonar de viola d’archo tastada de Silvestro Ganassi dal fontego, Venedig 1542 GIULIO SEGNI (1498-1561) Ricercare XV 5:58 Musica nova accomodata per cantar et sonar sopra organi; et altri strumenti, Venedig 1540, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI Madrigal 2:29 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 GIACOMO FOGLIANO (1468-1548) Io vorrei Dio d’amore 2:09 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch GIACOMO FOGLIANO Recercada 1:30 Intavolature manuscritte per organo, Archivio della parrochia di Castell’Arquato ADRIANO WILLAERT Ricercar X 5:09 Musica nova [...], Venedig 1540 Diminutionen*: Félix Verry SILVESTRO GANASSI Recercar Secondo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 SILVESTRO GANASSI Recerchar primo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Venedig 1542 JACQUES ARCADELT Quando co’l dolce suono 2:42 Il primo libro di Madrigali d’Arcadelt [...], Venedig 1539 Diminutionen*: T. -

Otros Instrumento Cuerda Códigos EN 04-21

Price List 2021 Lute Bandurria Cuatro Timple Ukulele (April) Lute Top (460x180x4 mm)x2Back (460x180x4 mm)x2Side (700x100x3,5 mm) x2 Fingerboard 420x75x9 mm Euro. Spruce 304 5,40 € Curly Maple 469 30,20 € Curly Maple 397 22,00 € African Ebony FSC 100% 8295 12,40 € Canad. Cedar 754 6,10 € *Cocobolo 6942 34,50 € *Cocobolo 6944 24,80 € African Ebony 1279 10,50 € Engel. Spruce 331 4,00 € Exotic Ebony 8613 34,50 € Exotic Ebony 8614 24,80 € Defective African Ebony Walnut 2707 18,90 € Walnut 2692 15,30 € 420x66x9mm 1281 0,70 € Santos Rosewood 8346 26,80 € Santos Rosewood 8350 19,60 € * Indian Rosewood 3290 4,50 € * Indian Rosewood 3346 38,80 € *Indian Rosewood 3228 27,60 € Neck 580x75x22 mm * Madagascar Ros. 3083 34,50 € *Madagascar Ros. 3040 24,80 € *Mahogany 8674 12,40 € Sapele 4357 13,00 € Sapele 4338 10,50 € * Mahogany FSC 100% 9807 14,90 € Sycamore 4382 13,00 € Sycamore 7430 10,50 € African Mahogany 8676 6,90 € Ziricote 8216 52,00 € Ziricote 8218 35,90 € * Honduras Cedar 8675 8,00 € Finished Neck Scale:500 * Af. Mahogany + Mex. Gran. 11204 69,00 € Bandurria * Cedar + St. Rosw. Headplate 11206 73,00 € Top (400x160x4 mm)x2 Back (400x160x4 mm)x2 Side (550x100x3,5mm)x2 Fingerboard 420x66x9 mm Euro. Spruce 302 5,90 € Curly Maple 470 23,30 € Curly Maple 398 19,60 € African Ebony FSC 100% 7571 10,60 € Canad. Cedar 756 5,50 € *Cocobolo 6943 29,40 € *Cocobolo 6945 22,00 € African Ebony 1235 4,80 € Engel. Spruce 6767 3,40 € Exotic Ebony 8615 29,40 € Exotic Ebony 8616 22,00 € Defective African Ebony Walnut 6946 17,20 € Walnut 6947 14,20 € 420x66x9mm 1281 0,70 € Santos Rosewood 8347 20,70 € Santos Rosewood 8351 17,20 € * Indian Rosewood 3263 4,00 € * Indian Rosewood 3347 33,80 € * Indian Rosewood 3230 26,00 € Neck 450x75x22 mm * Madagascar Ros. -

High School Madrigals May 13, 2020

Concert Choir Virtual Learning High School Madrigals May 13, 2020 High School Concert Choir Lesson: May 13, 2020 Objective/Learning Target: students will learn about the history of the madrigal and listen to examples Bell Work ● Complete this google form. A Brief History of Madrigals ● 1501- music could be printed ○ This changed the game! ○ Reading music became expected ● The word “Madrigal” was first used in 1530 and was for musical settings of Italian poetry ● The Italian Madrigal became popular because the emphasis was on the meaning of the text through the music ○ It paved the way to opera and staged musical productions A Brief History of Madrigals ● Composers used text from popular poets at the time ● 1520-1540 Madrigals were written for SATB ○ At the time: ■ Cantus ■ Altus ■ Tenor ■ Bassus ○ More voices were added ■ Labeled by their Latin number ● Quintus (fifth voice) ● Sextus (sixth voice) ○ Originally written for 1 voice on a part A Brief History of Madrigals Homophony ● In the sixteenth century, instruments began doubling the voices in madrigals ● Madrigals began appearing in plays and theatre productions ● Terms to know: ○ Homophony: voices moving together with the same Polyphony rhythm ○ Polyphony: voices moving with independent rhythms ● Early madrigals were mostly homophonic and then polyphony became popular with madrigals A Brief History of Madrigals ● Jacques Arcadelt (1507-1568)was an Italian composer who used both homophony and polyphony in his madrigals ○ Il bianco e dolce cigno is a great example ● Cipriano de Rore -

Jíbaro Music of Puerto Rico) a Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed By: Bethany Grant-Rodriguez University of Washington

Jíbaro Hasta el Hueso: Jíbaro to the Bone (Jíbaro music of Puerto Rico) A Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed by: Bethany Grant-Rodriguez University of Washington Summary: This unit focuses on the jíbaro music of Puerto Rico. Students will learn to identify the characteristic instruments, rhythms, and sound of jíbaro music, as well as appreciate the improvisatory skills of the poet/singers known as trovatores. Students will listen, perform, analyze, and create original verses using a common jíbaro poetic structure (the seis). This unit will also highlight important theme of social justice, which is often the topic of jíbaro songs. Suggested Grade Levels: 3–5 or 6–8 Country: USA (unincorporated) Region: Puerto Rico Culture Group: Puerto Ricans (Boricuas) Genre: Jíbaro Instruments: Voice, body percussion, bongos, guiros, xylophones, guitar/piano (optional addition for harmonic support for grades 3–5) Language: Spanish Co-Curricular Areas: Social studies, language arts National Standards: 2, 3, 4, 6, 9 Prerequisites: Basic familiarity with how to play xylophones, familiarity with instrument timbres, ability to keep a steady beat in a group music setting, some experience with reading and writing poetry (knowledge of rhyme scheme and form). Objectives: Listen: Students will recognize and identify the characteristic sound of jíbaro music (6, 9) Play: Students will play classroom percussion instruments to reproduce the harmony and rhythms of jíbaro music (2) Compose: Students will compose original verses to create their very own seis (4) *Improvise: Students will vocally improvise a melody for their original verse in the jíbaro style (like the Puerto Rican trovatores) (3) *This objective is for more confident and advanced musicians. -

Rippling Notes” to the Federal Way Performing Arts & Event Center Sunday, September 17 at 3:00 Pm

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT August 23, 2017 Scott Abts Marketing Coordinator [email protected] DOWNLOAD IMAGES & VIDEO HERE 253-835-7022 MASTSER TIMPLE MUSICIAN GERMÁN LÓPEZ BRINGS “RIPPLING NOTES” TO THE FEDERAL WAY PERFORMING ARTS & EVENT CENTER SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 17 AT 3:00 PM The Performing Arts & Event Center of Federal Way welcomes Germán (Pronounced: Herman) López, Sunday, September 17 at 3:00 PM. On stage with guitarist Antonio Toledo, Germán harnesses the grit of Spanish flamenco, the structure of West African rhythms, the flourishing spirit of jazz, and an innovative 21st century approach to performing “island music.” His principal instrument is one of the grandfathers of the ‘ukelele’, and part of the same instrumental family that includes the cavaquinho, the cuatro and the charango. Germán López’s music has been praised for “entrancing” performances of “delicately rippling notes” (Huffington Post), notes that flow from musical traditions uniting Spain, Africa, and the New World. The “timple” is a diminutive 5 stringed instrument intrinsic to music of the Canary Islands. Of all the hypotheses that exist about the origin of the “timple”, the most widely accepted is that it descends from the European baroque guitar, smaller than the classical guitar, and with five strings. Tickets for Germán López are on sale now at www.fwpaec.org or by calling 2535-835-7010. The Performing Arts and Event Center is located at 31510 Pete von Reichbauer Way South, Federal Way, WA 98003. We’ll see you at the show! About the PAEC The Performing Arts & Event Center opened August of 2017 as the South King County premier center for entertainment in the region. -

Classical Guitar at Sundin Hall in St. Paul!

A Publication of the Minnesota Guitar Society • P.O. Box 14986 • Minneapolis, MN 55414 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2008 VOL. 24 NO. 6 Classical Guitar at Sundin Hall in St. Paul! Saturday, Nov 15th, 8 pm Classical guitarist Pable Sainz Villegas from Spain Saturday, Dec 6th, 8 pm The acclaimed Minneapolis Guitar Quartet Local Artists Series concert at Banfill-Locke Center for the Arts Sunday, Nov 9th, 2 pm Classical guitarist Steve Newbrough Also In This Issue Jay Fillmore on Guitar Harmonics review of Sharon Isbin masterclass more News and Notes Minnesota Guitar Society Board of Directors Newsletter EDITOR OFFICERS: BOARD MEMBERS: Paul Hintz PRESIDENT Joe Haus Christopher Becknell PRODUCTION Mark Bussey VICE-PRESIDENT Joanne Backer i draw the line, inc. Steve Kakos ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Joe Hagedorn David’s Print Shop Steven Newbrough DISTRIBUTION TREASURER Jim Campbell Christopher Olson Todd Tipton Mark Bussey MANAGING DIRECTOR Paul Hintz Todd Tipton Web Site Production SECRETARY Alan Norton Brent Weaver Amy Lytton <http://www.mnguitar.org> Minnesota Guitar Society The Minnesota Guitar Society concert season is co-sponsored by Mission Statement Sundin Hall. This activity is made To promote the guitar, in all its stylistic and cultural diversity, possible in part by a grant from the through our newsletter and through our sponsorship of Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation by the Minnesota public forums, concerts, and workshops. State Legislature and a grant from To commission new music and to aid in its the National Endowment for the promotion, publication, and recording. Arts. Matching funds have been To serve as an educational and social link between amateur provided by General Mills, AT&T, and Ameriprise Financial. -

HISPANIC MUSIC for BEGINNERS Terminology Hispanic Culture

HISPANIC MUSIC FOR BEGINNERS PETER KOLAR, World Library Publications Terminology Spanish vs. Hispanic; Latino, Latin-American, Spanish-speaking (El) español, (los) españoles, hispanos, latinos, latinoamericanos, habla-español, habla-hispana Hispanic culture • A melding of Spanish culture (from Spain) with that of the native Indian (maya, inca, aztec) Religion and faith • popular religiosity: día de los muertos (day of the dead), santería, being a guadalupano/a • “faith” as expession of nationalistic and cultural pride in addition to spirituality Diversity within Hispanic cultures Many regional, national, and cultural differences • Mexican (Southern, central, Northern, Eastern coastal) • Central America and South America — influence of Spanish, Portuguese • Caribbean — influence of African, Spanish, and indigenous cultures • Foods — as varied as the cultures and regions Spanish Language Basics • a, e, i, o, u — all pure vowels (pronounced ah, aey, ee, oh, oo) • single “r” vs. rolled “rr” (single r is pronouced like a d; double r = rolled) • “g” as “h” except before “u” • “v” pronounced as “b” (b like “burro” and v like “victor”) • “ll” and “y” as “j” (e.g. “yo” = “jo”) • the silent “h” • Elisions (spoken and sung) of vowels (e.g. Gloria a Dios, Padre Nuestro que estás, mi hijo) • Dipthongs pronounced as single syllables (e.g. Dios, Diego, comunión, eucaristía, tienda) • ch, ll, and rr considered one letter • Assigned gender to each noun • Stress: on first syllable in 2-syllable words (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) • Stress: on penultimate syllable in 3 or more syllables (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) Any word which doesn’t follow these stress rules carries an accent mark — é, á, í, ó, étc. -

John Griffiths, Vihuela Vihuela Hordinaria & Guitarra Española

John Griffiths, vihuela 7:30 pm, Thursday April 14, 2016 St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church Miami, Florida Society for Seventeenth-Century Music Annual Conference Vihuela hordinaria & guitarra española th th 16 and 17 -century music for vihuela and guitar So old, so new Fantasía 8 Luis Milán Fantasía 16 (c.1500–c.1561) Fantasía 11 Counterpoint to die for Fantasía sobre un pleni de contrapunto Enríquez de Valderrábano Soneto en el primer grado (c.1500–c.1557) Fantasía del author Miguel de Fuenllana Duo de Fuenllana (c.1500–1579) Strumming my pain Jácaras Antonio de Santa Cruz (1561–1632) Jácaras Santiago de Murcia (1673–1739) Villanos Francisco Guerau Folías (1649–c.1720) Folías Gaspar Sanz (1640–1710) Winds of change Tres diferencias sobre la pavana Valderrábano Diferencias sobre folias Anon. Diferencias sobre zarabanda John Griffiths is a researcher of Renaissance music and culture, especially solo instrumental music from Spain and Italy. His research encompasses broad music-historical studies of renaissance culture that include pedagogy, organology, music printing, music in urban society, as well as more traditional areas of musical style analysis and criticism, although he is best known for his work on the Spanish vihuela and its music. He has doctoral degrees from Monash and Melbourne universities and currently is Professor of Music and Head of the Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music at Monash University, as well as honorary professor at the University of Melbourne (Languages and Linguistics), and an associate at the Centre d’Etudes Supérieures de la Renaissance in Tours. He has published extensively and has collaborated in music reference works including The New Grove, MGG and the Diccionario de la música española e hispanoamericana. -

Une Jeune Pucelle 3’43 Se Chante Sur « Une Jeune Fillette »

menu tracklist texte en français text in english textes chantés / lyrics AU SAINCT NAU 1 Procession Conditor alme syderum 2’40 2 Procession Conditor le jour de Noel 1’20 Se chante sur « Conditor alme syderum » 3 Eustache Du Caurroy Fantaisie n°4 sur Conditor alme syderum 1’48 (Orgue seul) 4 Jean Mouton - Noe noe psallite noe 3’21 5 Jacques Arcadelt - Missa Noe noe, Kyrie 8’06 Alterné avec le Kyrie « le jour de noël », qui se chante sur Kyrie fons bonitatis 6 Clément Janequin - Il estoyt une fillette 3’01 Se chante sur « Il estoit une fillette » 7 Anonyme/Christianus de Hollande Plaisir n’ay plus que vivre en desconfort 4’03 Se chante sur « Plaisir n’ay plus » 8 Claudin de Sermizy Dison Nau à pleine teste 3’27 Se chante sur « Il est jour, dist l’alouette » 9 Claudin de Sermizy - Au bois de deuil 3’49 Se chante sur « Au joly boys » 10 Eustache Du Caurroy Fantaisie n°31 sur Une jeune fillette 1’48 (Orgue seul) 3 11 Loyset Pieton O beata infantia 8’20 12 Eustache Du Caurroy Fantaisie n°30 sur Une jeune fillette 1’37 (Orgue seul) 13 Eustache Du Caurroy Une jeune pucelle 3’43 Se chante sur « Une jeune fillette » 14 Guillaume Costeley - Allons gay bergiere 1’37 15 Claudin de Sermizy L’on sonne une cloche 3’35 Se chante sur « Harri bourriquet » 16 Anonyme - O gras tondus 1’42 17 Claudin de Sermizy Vous perdez temps heretiques infames 2’16 Se chante sur « Vous perdez temps de me dire mal d’elle » 18 Claude Goudimel Esprit divins, chantons dans la nuit sainte 2’16 Se chante sur « Estans assis aux rives aquatiques » (Ps. -

FAKING a BAROQUE GUITAR Jay Reynolds Freeman Summary: ======I Converted a Baritone Ukulele Into an Ersatz Baroque Guitar

FAKING A BAROQUE GUITAR Jay Reynolds Freeman Summary: ======= I converted a baritone ukulele into an ersatz Baroque guitar. It was a simple modification, and the result is a charming little guitar. Background: ========== I don't know how an electric guitar player like me got interested in Baroque music, but after noodling with "Canarios" on a Stratocaster for a few months, I began wondering what it sounded like on the guitars Gaspar Sanz played. Recordings of Baroque guitar music abound, but the musicians commonly use contemporary classical guitars, which are almost as far removed from the Baroque guitar as is my Strat. Several luthiers build replica Baroque guitars, but they are very expensive, and I couldn't find one locally. I am only a very amateur luthier. With lots of work and dogged stubbornness, I might be able to scratch-build a playable Baroque guitar replica, but I wasn't sure that my level of interest warranted an elaborate project, so I dithered. Then I met someone on the web who had actually heard a Baroque guitar; he said it sounded more like a modern ukulele than a modern classical guitar, though with a softer, richer sound. That started me thinking about a more modest project -- converting a modern instrument into a Baroque guitar. I had gotten a Baroque guitar plan from the Guild of American Luthiers. Its light construction, small body, and simple bracing were indeed ukulele-like. A small classical guitar might have made a better starting point, but it is hard to add tuners to a slotted headstock, and I find classical necks awkwardly broad, so a large ukulele was more promising. -

Wwciguide April 2019.Pdf

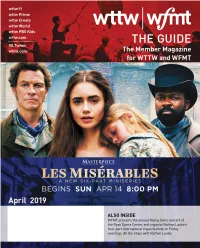

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center This month, we are excited to bring you a sweeping new adaptation of Victor Hugo’s 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 classic novel Les Misérables. This new six-part series, featuring an all-star cast including Dominic West, David Oyelowo, and recent Oscar winner Olivia Colman, tells the story of fugitive Jean Valjean, his relentless pursuer Inspector Javert, and other colorful characters Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 in turbulent 19th century France. We hope you’ll join us on Sunday nights for this epic Member and Viewer Services drama, and explore extra content on our website including episode recaps and fact vs. (773) 509-1111 x 6 fiction. If spring is a time of renewal, that is also certainly true of some of WTTW’s offerings Websites wttw.com in April, including eagerly awaited new seasons of three very different British detective wfmt.com series – Father Brown, Death in Paradise, and Unforgotten – and Mexico: One Plate at a Time, Jamestown, and Islands Without Cars. On wttw.com, as American Masters features Publisher newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer, we profile Chicago winners of the journalism and Anne Gleason arts award that bears his name, and highlight some extraordinary African American Art Director Tom Peth entrepreneurs in Chicago. WTTW Contributors WFMT will present the annual Rising Stars concert of the Ryan Opera Center, and Julia Maish Dan Soles organist Nathan Laube’s four-part international organ festival on Friday evenings, All the WFMT Contributors Stops with Nathan Laube. -

Play Days 2011 Approach and Start Off-Topic

Volume 26, No. 6 April 2011 The Making of On Cold Mountain— The Journey to On Cold Mountain Songs on Poems of Gary Snyder There is a natural way to write a narrative and an artful way. The natural way, according to the rhetoricians, is to Roy Whelden The editor of this newsletter, Peter Brodigan, has asked me to write about the recently released recording On Cold Mountain—Songs on Poems of Gary Snyder (Innova Records 795). The CD contains four new song cycles written by Fred Frith, W.A. Mathieu, Robert Morris, and me. The performers are the contralto Karen Clark and the Galax Quartet: David Wilson and Elizabeth Blumenstock, violins; Roy Whelden, viola da gamba; David Morris, ’cello. Peter felt that I, as a composer and the viola da gamba player in the Galax Quartet, might have something interesting to say concerning the making of the album. In the account which follows, I try to write to the interests in particular of the viol playing community. start at the beginning and press toward the end, The release party for the new CD takes place on April 25 chronologically. The artful way is to start at a mid-point from 5 to 7 p.m. at the Musical Offering Cafe on 2430 and allow the story to unfold. Both ways are of equal Bancroft Avenue in Berkeley. A few selections from the validity. album will be performed. Profits from sales at this event, The problem with the natural way of telling this particular as well as from items ordered online the same day story, the making of On Cold Mountain, is that the at www.galaxquartet.org, will be donated to the Pacifica beginning is nebulous.