Jerusalem As Palimpsest the Architectural Footprint of the Crusaders in the Contemporary City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holy Land Itinerary December 16, 2008 - January 1, 2009

Holy Land Itinerary December 16, 2008 - January 1, 2009 December 16: Depart Houston IAH Delta Airlines, 5:55 p.m. via Atlanta to Tel Aviv. December 17: O Wisdom, O Holy Word of God, you govern all creation with your strong yet tender care. Come and show your people the way to salvation. Arrive Tel Aviv 5:25 p.m. Depart by motor coach for Haifa. Mass/Dinner/Accommodations at Carmelite Guest House – Stella Maris. December 18: O Adonai, who showed yourself to Moses in the burning bush, who gave him the holy law on Sinai mountain: come, stretch out your mighty hand to set us free. Mass in Church of the Prophet Elijah’s cave on Mt. Carmel. Depart for Nazareth via Acre, site of Crusader city and castle (Richard the Lion-Hearted) – lunch stop; to Sepphoris to visit an archeological dig of city where Joseph and Jesus may probably have worked (4 miles from Nazareth) to help build one of Herod’s great cities; to Nazareth. Dinner/Accommodations at Sisters of Nazareth Guest House adjacent to the Basilica of the Annunciation and over the probable site of the tomb of St. Joseph. December 19: O Flower of Jesse’s stem, you have been raised up as a sign for all peoples; kings stand silent in your presence; the nations bow down in worship before you. Come, let nothing keep you from coming to our aid. Mass in ancient Grotto of the Annunciation (home of Joachim and Ann); visit Mary’s well, Church of the Nutrition over home of Holy Family, International Marian Center. -

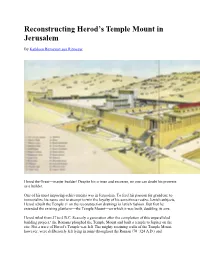

Reconstructing Herod's Temple Mount in Jerusalem

Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem By Kathleen RitmeyerLeen Ritmeyer Herod the Great—master builder! Despite his crimes and excesses, no one can doubt his prowess as a builder. One of his most imposing achievements was in Jerusalem. To feed his passion for grandeur, to immortalize his name and to attempt to win the loyalty of his sometimes restive Jewish subjects, Herod rebuilt the Temple (1 on the reconstruction drawing) in lavish fashion. But first he extended the existing platform—the Temple Mount—on which it was built, doubling its size. Herod ruled from 37 to 4 B.C. Scarcely a generation after the completion of this unparalleled building project,a the Romans ploughed the Temple Mount and built a temple to Jupiter on the site. Not a trace of Herod’s Temple was left. The mighty retaining walls of the Temple Mount, however, were deliberately left lying in ruins throughout the Roman (70–324 A.D.) and Byzantine (324–640 A.D.) periods—testimony to the destruction of the Jewish state. The Islamic period (640–1099) brought further eradication of Herod’s glory. Although the Omayyad caliphs (whose dynasty lasted from 633 to 750) repaired a large breach in the southern wall of the Temple Mount, the entire area of the Mount and its immediate surroundings was covered by an extensive new religio-political complex, built in part from Herodian ashlars that the Romans had toppled. Still later, the Crusaders (1099–1291) erected a city wall in the south that required blocking up the southern gates to the Temple Mount. -

Renaissance and Baroque Art

Brooks Education (901)544.6215 Explore. Engage. Experience. Renaissance and Baroque Art Memphis Brooks Museum of Art Permanent Collection Tours German, Saint Michael, ca. 1450-1480, limewood, polychromed and gilded , Memphis Brooks Museum of Art Purchase with funds provided by Mr. and Mrs. Ben B. Carrick, Dr. and Mrs. Marcus W. Orr, Fr. And Mrs. William F. Outlan, Mr. and Mrs. Downing Pryor, Mr. and Mrs. Richard O. Wilson, Brooks League in memory of Margaret A. Tate 84.3 1 Brooks Education (901)544.6215 Explore. Engage. Experience. Dear Teachers, On this tour we will examine and explore the world of Renaissance and Baroque art. The French word renaissance is translated as “rebirth” and is described by many as one of the most significant intellectual movements of our history. Whereas the Baroque period is described by many as a time of intense drama, tension, exuberance, and grandeur in art. By comparing and contrasting the works made in this period students gain a greater sense of the history of European art and the great minds behind it. Many notable artists, musicians, scientists, and writers emerged from this period that are still relished and discussed today. Artists and great thinkers such as Leonardo Da Vinci, Michaelangelo Meisi da Caravaggio, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, Dante Alighieri, Johann Sebastian Bach, and Galileo Galilei were working in their respective fields creating beautiful and innovative works. Many of these permanent collection works were created in the traditional fashion of egg tempera and oil painting which the students will get an opportunity to try in our studio. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

THE CRUSADES Toward the End of the 11Th Century

THE MIDDLE AGES: THE CRUSADES Toward the end of the 11th century (1000’s A.D), the Catholic Church began to authorize military expeditions, or Crusades, to expel Muslim “infidels” from the Holy Land!!! Crusaders, who wore red crosses on their coats to advertise their status, believed that their service would guarantee the remission of their sins and ensure that they could spend all eternity in Heaven. (They also received more worldly rewards, such as papal protection of their property and forgiveness of some kinds of loan payments.) ‘Papal’ = Relating to The Catholic Pope (Catholic Pope Pictured Left <<<) The Crusades began in 1095, when Pope Urban summoned a Christian army to fight its way to Jerusalem, and continued on and off until the end of the 15th century (1400’s A.D). No one “won” the Crusades; in fact, many thousands of people from both sides lost their lives. They did make ordinary Catholics across Christendom feel like they had a common purpose, and they inspired waves of religious enthusiasm among people who might otherwise have felt alienated from the official Church. They also exposed Crusaders to Islamic literature, science and technology–exposure that would have a lasting effect on European intellectual life. GET THE INFIDELS (Non-Muslims)!!!! >>>> <<<“GET THE MUSLIMS!!!!” Muslims From The Middle East VS, European Christians WHAT WERE THE CRUSADES? By the end of the 11th century, Western Europe had emerged as a significant power in its own right, though it still lagged behind other Mediterranean civilizations, such as that of the Byzantine Empire (formerly the eastern half of the Roman Empire) and the Islamic Empire of the Middle East and North Africa. -

Chapter 3 Translatio Templi: a Conceptual Condition for Jerusalem References in Medieval Scandinavia

Eivor Andersen Oftestad Chapter 3 Translatio Templi: A Conceptual Condition for Jerusalem References in Medieval Scandinavia The present volume traces Jerusalem references in medieval Scandinavia. An impor- tant condition for these references is the idea of Christians’ continuity with the bibli- cal Jerusalem and the Children of Israel. Accordingly, as part of an introduction to the topic, an explanation of this idea is useful and is given in the following. According to the Bible, God revealed himself to the Jews and ordered a house to be built for his dwelling among his people.1 The high priest was the only one allowed to enter His presence in the innermost of the Temple – the Holy of Holies was the exclusive meeting place between God and man. This was where the Ark of the Covenant was preserved, and it was the place for the offering at the Atonement day. The Old Testament temple cult is of fundamental significance for the legitimation of the Christian Church. Although this legitimation has always depended on the idea of continuity between Jewish worship and Christian worship, the continuity has been described variously throughout history. To the medieval Church, a transfer of both divine presence and sacerdotal authority from the Old to the New Covenant was crucial. At the beginning of the twelfth century, which was both in the wake of the first crusade and the period when the Gregorian papacy approved the new Scandinavian Church province, a certain material argument of continuity occurred in Rome that can be described according to a model of translatio templi.2 The notion of translatio can be used to characterize a wide range of phenomena and has been one of several related approaches to establish continuity over time in western history.3 The “translation of the empire,” translatio imperii, was defined by 1 1 Kgs 6:8. -

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city. -

A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2014 A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E. Tobias Osterhaug Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Osterhaug, Tobias, "A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E." (2014). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 25. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/25 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Tobias Osterhaug History 499/Honors 402 A Political History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem 1099 to 1187 C.E. Introduction: The first Crusade, a massive and unprecedented undertaking in the western world, differed from the majority of subsequent crusades into the Holy Land in an important way: it contained no royalty and was undertaken with very little direct support from the ruling families of Western Europe. This aspect of the crusade led to the development of sophisticated hierarchies and vassalages among the knights who led the crusade. These relationships culminated in the formation of the Crusader States, Latin outposts in the Levant surrounded by Muslim states, and populated primarily by non-Catholic or non-Christian peoples. Despite the difficulties engendered by this situation, the Crusader States managed to maintain control over the Holy Land for much of the twelfth century, and, to a lesser degree, for several decades after the Fall of Jerusalem in 1187 to Saladin. -

The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218

IACOBVS REVIST A DE ESTUDIOS JACOBEOS Y MEDIEVALES C@/llOj. ~1)OI I 1 ' I'0 ' cerrcrzo I~n esrrrotos r~i corrnrro n I santiago I ' s a t'1 Cl fJ r1 n 13-14 SAHACiVN (LEON) - 2002 CENTRO DE ESTVDIOS DEL CAMINO DE SANTIACiO The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218 Laszlo VESZPREMY Instituto Historico Militar de Hungria Resumen: Las relaciones entre los cruzados y el Reino de Hungria en el siglo XIII son tratadas en la presente investigacion desde la perspectiva de los hungaros, Igualmente se analiza la politica del rey cruzado magiar Andres Il en et contexto de los Balcanes y del Imperio de Oriente. Este parece haber pretendido al propio trono bizantino, debido a su matrimonio con la hija del Emperador latino de Constantinopla. Ello fue uno de los moviles de la Quinta Cruzada que dirigio rey Andres con el beneplacito del Papado. El trabajo ofre- ce una vision de conjunto de esta Cruzada y del itinerario del rey Andres, quien volvio desengafiado a su Reino. Summary: The main subject matter of this research is an appro- ach to Hungary, during the reign of Andrew Il, and its participation in the Fifth Crusade. To achieve such a goal a well supported study of king Andrew's ambitions in the Balkan region as in the Bizantine Empire is depicted. His marriage with a daughter of the Latin Emperor of Constantinople seems to indicate the origin of his pre- tensions. It also explains the support of the Roman Catholic Church to this Crusade, as well as it offers a detailed description of king Andrew's itinerary in Holy Land. -

CGS Newsletter

Preparing for Easter at Home as a Family Listening to God with Children during Holy Week As a family, we can prepare spiritually and physically by listening to and reflecting upon the Word of God together with our children. Most interestingly, without the sacraments - the bread and wine - we contemplate on the Word of God, discovering more earnestly how God comes to be with us through the Word. To enter more deeply into Easter preparation, we transport ourselves to the historical place and time of the Paschal Mystery, before bringing our focus on the Holy Triduum. Biblical Geography: The Land of Israel City of Jerusalem. The children in the Material at Home. Find a physical map from a Atrium are initiated into the geography of biblical atlas or a virtual map of Israel online. Israel, focusing on its principal cities. During Lent, we deep-dive into the city of The Holy Land Model of Jerusalem (official site) Jerusalem and important places that tell or see a video overview here. This is a 1:50 us about Jesus' final days on earth with three-dimensional scale model of the city of His disciples. Jerusalem in the Second Temple Period. City of Jerusalem Map You may print this for the children to colour in and refer to while reading scripture. After looking at how the city was laid out, with its walls and its grand Temple, we then name and look more closely at the places where Jesus walked, giving children only a brief description. We focus on the location of: (1) the Cenacle, (2) the house of Caiaphas, (3) the Antonia Tower, (4) the Garden of Olives, (5) Calvary and (6) the tomb of the resurrection (RPC1, p. -

What Was 'The Enlightenment'? We Hear About It All the Time. It Was A

What Was ‘The Enlightenment’? We hear about it all the time. It was a pivotal point in European history, paving the way for centuries of history afterward, but what was ‘The Enlightenment’? Why is it called ‘The Enlightenment’? Why did the period end? The Enlightenment Period is also referred to as the Age of Reason and the “long 18th century”. It stretched from 1685 to 1815. The period is characterized by thinkers and philosophers throughout Europe and the United States that believed that humanity could be changed and improved through science and reason. Thinkers looked back to the Classical period, and forward to the future, to try and create a trajectory for Europe and America during the 18th century. It was a volatile time marked by art, scientific discoveries, reformation, essays, and poetry. It begun with the American War for Independence and ended with a bang when the French Revolution shook the world, causing many to question whether ideas of egalitarianism and pure reason were at all safe or beneficial for society. Opposing schools of thought, new doctrines and scientific theories, and a belief in the good of humankind would eventually give way the Romantic Period in the 19th century. What is Enlightenment? Philosopher Immanuel Kant asked the self-same question in his essay of the same name. In the end, he came to the conclusion: “Dare to know! Have courage to use your own reason!” This was an immensely radical statement for this time period. Previously, ideas like philosophy, reason, and science – these belonged to the higher social classes, to kings and princes and clergymen. -

The Virgin Mary As Mediatrix Between Christians and Muslims in the Middle East

Marian Studies Volume 47 Marian Spirituality and the Interreligious Article 10 Dialogue 1996 The irV gin Mary as Mediatrix Between Christians and Muslims in the Middle East Otto F. A. Meinardus Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Meinardus, Otto F. A. (1996) "The irV gin Mary as Mediatrix Between Christians and Muslims in the Middle East," Marian Studies: Vol. 47, Article 10. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol47/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Meinardus: Mediatrix between Christians and Muslims THE VIRGIN MARY AS MEDIATRIX BETWEEN CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS IN THE MIDDLE EAST Otto E A. Meinardus, Ph.D.* In spite of deep-seated christological and soteriological dif ferences between Orthodox Christianity and Islam, there are some areas in which Christian and Muslim prayer converge which could be the basis of dialogue. In the popular piety of the Egyptians, the Virgin Mary, mother ofJesus, can play the role of mediatrix between Muslims and Christians. The subject is di verse and voluminous, so I will limit myself to a few aspects of the theme.Because of my long stay in the Middle East, especially in Egypt, I can describe some of the ways in which a devotion to the Virgin Mary brings together Christians and Muslims. The profound and deep esteem of the Orthodox Christians in the East for the Virgin Mary is well known.Their devotion to her as the Theotokos constitutes an integral part of their litur gical life and popular piety.