Slacum Memoirs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Henry Woodhouse Collection Relating to George Washington [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Mon Jan 12 09:47:32 E](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4545/henry-woodhouse-collection-relating-to-george-washington-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-mon-jan-12-09-47-32-e-294545.webp)

Henry Woodhouse Collection Relating to George Washington [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Mon Jan 12 09:47:32 E

Henry Woodhouse Collection Relating to George Washington A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms011233 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm76057133 Prepared by Wilhelmena B. Curry Collection Summary Title: Henry Woodhouse Collection Relating to George Washington Span Dates: 1656-1930 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1825-1887) ID No.: MSS57133 Collector: Woodhouse, Henry, 1884- Extent: 4,500 items ; 7 containers plus 1 oversize ; 2.8 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Editor and author. Correspondence, deeds, wills, testaments, indentures, bonds, surveys, maps, plats, financial and legal records, clippings, and other papers relating principally to George Washington, the Washington family, and its descendants. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Lee, Francis Lightfoot, 1734-1797. Lee, Richard Henry, 1732-1794. Washington family. Washington, Augustine, approximately 1694-1743. Washington, George Corbin, 1789-1854. Washington, George, 1732-1799--Family. Washington, George, 1732-1799. Washington, H. A. (Henry Augustine), 1820-1858. Washington, Lawrence, 1718-1752. Washington, Robert James, 1841- Washington, William Augustine, 1757-1810. Woodhouse, Henry, 1884- Subjects Land grants--Virginia--Westmoreland County. Places Wakefield (Westmoreland County, Va.) Occupations Authors. Editors. -

GEORGE WASHINGTON's MOUNT VERNON (Slide: Aerial View) When George Washington Died in 1799, His Mount Vernon Estate Was at Its Hi

GEORGE WASHINGTON'S MOUNT VERNON (Slide: Aerial View) When George Washington died in 1799, his Mount Vernon estate was at its highest point of development. In the 45 years since he had become master of Mount Vernon, Washington had completely transformed the small plantation he had inherited from his older half brother, Lawrence. This aerial view shows the estate as it appears today, and we believe, as it appeared during the final years of General Washington's life. Mount Vernon's preservation is the achievement of the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union, which has owned the estate since 1858. Over the years, the goal of the Association has been to restore Mount Vernon to its original condition and to present it to the public. (Slide: East Front) Today our visitors see Washington/s 500 acre "Mansion House Form," the formal pleasure grounds of the 8,000 acre plantation that existed in the 18th century. The Mansion House itself, seated on a high bluff with a commanding view of the Potomac River and the Maryland shoreline beyond,is the focal point in a village-like setting of outbuildings, formal gardens and grounds .. This neat and elegant estate was the creation of George Washington, who personally designed and laid it out. (Slide: Houdon Bust) Washington is of course best remembered for his services as ~ommonder-in-Chief and president, but at Mount Vernon we celebrate -2- the memory of the Virginia farmer and family man. There are many monuments to George Washington. The visitor to Mount Vernon can discover the complex and passionate man behind the austere, remote historical figure. -

Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through His Life at Arlington House

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2020 The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House Cecilia Paquette University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Paquette, Cecilia, "The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House" (2020). Master's Theses and Capstones. 1393. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/1393 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE THAT BUILT LEE Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House BY CECILIA PAQUETTE BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2017 BFA, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 2014 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History September, 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2020 Cecilia Paquette ii This thesis was examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in History by: Thesis Director, Jason Sokol, Associate Professor, History Jessica Lepler, Associate Professor, History Kimberly Alexander, Lecturer, History On August 14, 2020 Approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. !iii to Joseph, for being my home !iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisory committee at the University of New Hampshire. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Fred A

Qeorge Washington Birthplace UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fred A. Seaton, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER TWENTY-SIX This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archcological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents. GEORGE WASHINGTON BIRTHPLACE National Monument Virginia by J. Paul Hudson NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 26 Washington, D. C, 1956 The National Park System, of which George Washington Birthplace National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. Qontents Page JOHN WASHINGTON 5 LAWRENCE WASHINGTON 6 AUGUSTINE WASHINGTON 10 Early Life 10 First Marriage 10 Purchase of Popes Creek Farm 12 Building the Birthplace Home 12 The Birthplace 12 Second Marriage 14 Virginia in 1732 14 GEORGE WASHINGTON 16 THE DISASTROUS FIRE 22 A CENTURY OF NEGLECT 23 THE SAVING OF WASHINGTON'S BIRTHPLACE 27 GUIDE TO THE AREA 33 HOW TO REACH THE MONUMENT 43 ABOUT YOUR VISIT 43 RELATED AREAS 44 ADMINISTRATION 44 SUGGESTED READINGS 44 George Washington, colonel of the Virginia militia at the age of 40. From a painting by Charles Willson Peale. Courtesy, Washington and Lee University. IV GEORGE WASHINGTON "... His integrity was most pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known, no motives . -

George Washington Boyhood Home Site

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NFS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 WASHINGTON, GEORGE, BOYHOOD HOME SITE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service___________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: WASHINGTON, GEORGE, BOYHOOD HOME SITE Other Name/Site Number: Ferry Farm 44ST174 [Washington domestic complex archeological site number] 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 237 King's Highway (Virginia Route 3) Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Fredericksburg Vicinity: Fredericksburg State: Virginia County: Stafford Code: 179 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X_ Building(s): __ Public-Local: _ District: __ Public-State: _ Site: X Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 4 buildings 1 sites 1 structures 0 0 objects 6 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register:_0 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: None NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 WASHINGTON, GEORGE, BOYHOOD HOME SITE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Geographic Classification, 2003. 577 Pp. Pdf Icon[PDF – 7.1

Instruction Manual Part 8 Vital Records, Geographic Classification, 2003 Vital Statistics Data Preparation U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics Hyattsville, Maryland October, 2002 VITAL RECORDS GEOGRAPHIC CLASSIFICATION, 2003 This manual contains geographic codes used by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) in processing information from birth, death, and fetal death records. Included are (1) incorporated places identified by the U.S. Bureau of the Census in the 2000 Census of Population and Housing; (2) census designated places, formerly called unincorporated places, identified by the U.S. Bureau of the Census; (3) certain towns and townships; and (4) military installations identified by the Department of Defense and the U.S. Bureau of the Census. The geographic place of occurrence of the vital event is coded to the state and county or county equivalent level; the geographic place of residence is coded to at least the county level. Incorporated places of residence of 10,000 or more population and certain towns or townships defined as urban under special rules also have separate identifying codes. Specific geographic areas are represented by five-digit codes. The first two digits (1-54) identify the state, District of Columbia, or U.S. Possession. The last three digits refer to the county (701-999) or specified urban place (001-699). Information in this manual is presented in two sections for each state. Section I is to be used for classifying occurrence and residence when the reporting of the geographic location is complete. -

Holocaust Avengers: from "The Master Race" to Magneto I Kathrin Bower I

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Faculty Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Publications 2004 Holocaust Avengers: From "The aM ster Race" to Magneto Kathrin M. Bower University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/mlc-faculty-publications Part of the European History Commons, Illustration Commons, and the Place and Environment Commons Recommended Citation Bower, Kathrin M. "Holocaust Avengers: From "The asM ter Race" to Magneto." International Journal of Comic Art 6, no. 2 (2004): 182-94. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 182 Holocaust Avengers: From "The Master Race" to Magneto I Kathrin Bower I In the classic genealogy of the superhero, trauma is often the explanation ' or motivation for the hero's pursuit of justice or revenge. Origin stories for superheroes and supervillains frequently appear in the plots of comic books long after the characters were created and with the shift in the stable of artists involved, different and sometimes competing events in the characters' biographies are revealed. This is particularly true of series that have enjoyed long periods of popularity or those that were phased out and then later revived. The stimulus for this m1icle was the origin story conceived for the X-Men supervillain Magneto under Chris Claremont's plotting, after the series was resurrected in 197 5 and by the foregrounding of Magneto's Holocaust past in the opening sequence to Bryan Singer's 2000 filmX-Men. -

Tangents 1 Publishing Notes Letter from the Editors

summer 2006 the journal of the master of liberal arts program at stanford university in this issue... Essays by Jennifer Swanton Brown, Jennifer Burton, John Devine, Nancy Krajewski, Denise Osborne, Loren Szper, and Bryon Williams Fiction by Andy Grose Poems by Jennifer Swanton Brown, Tamara Tinker, and Mason Tobak summer 2006 the journal of the master of liberal arts program at stanford university volume 5 in this issue... 4 The Silk Horse Andy Grose 10 A Flood of Misborrowing: Sin and Deluge in Atrahasis and Genesis Bryon Williams 17 Three Poems of Love-Gone-Bad Mason Tobak 20 William James Observes San Francisco’s Reliance John Devine 27 The Burghers of Calais: A Personal Viewing Experience Jennifer Burton 31 Dionysus at Sea Tamara Tinker 32 Marriage in The Odyssey: An Intimate Conversation Jennifer Swanton Brown 34 A Deadly Agent of Change: The 1832 Parisian Cholera Epidemic and the French Public Health Movement Loren Szper 39 On the Path to the Pond Jennifer Swanton Brown 40 Kierkegaard in Wyoming: Reflections on Faith and Freedom in the High Mountains Nancy Krajewski 44 Do Laws Govern the Evolution of Technology? Denise Osborne 48 Contributors tangents 1 Publishing Notes letter from the editors This is a publication featuring the w ork of students and We are proud to present this issue of Tangents, the journal of the Stanfor d Master alumni of the Master of Liberal Arts Program at of Liberal Arts Program. For the fifth edition we ha ve chosen a diverse gr oup of Stanford University. works by students and alumni, including: Editor Oscar Firschein A story about two brothers and a powerful horse Assistant Editor Three quite varied poems Lindi Press Reviewers To celebrate the centenary, William James’s observations about the Oscar Firschein San Francisco earthquake Mary MacKinnen Lindi Press Some thoughts about marriage in The Odyssey Faculty Advisor A discussion of the 1832 Parisian Cholera epidemic Dr. -

![©[F3~~ GJ]Jrro~[M]~~~~©~ ~~[F3~[M][F)[Lrro~~ ~ 00Lr0@ ~ 00 ~ [F[Ffi @ ~ L!JJ [F[Ffi ~ ~ Lr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2395/%C2%A9-f3-gj-jrro-m-%C2%A9-f3-m-f-lrro-00lr0-00-f-ffi-l-jj-f-ffi-lr-1792395.webp)

©[F3~~ GJ]Jrro~[M]~~~~©~ ~~[F3~[M][F)[Lrro~~ ~ 00Lr0@ ~ 00 ~ [F[Ffi @ ~ L!JJ [F[Ffi ~ ~ Lr

MOUNT VERNON LIBRARY . - .- The Mtl1/orio! Mansion, ~~©[f3~~ GJ]Jrro~[M]~~~~©~ ~~[f3~[M][F)[Lrro~~ ~ 00lr0@ ~ 00 ~ [f[ffi @ ~ l!JJ [f[ffi ~ ~ lr VIRGINIA GEORGE WASHINGTON BIRTHPLACE NATIONAL MONUMENT United States Department of the Interior HAROLD L. ICKES. Secretary National Park Service. Nt;WTON B. DRURY, Director He who has gone down in history char- colonies to obtain .a cargo of tobacco. acterized as ..... first in war, first in peace John Washington soon married Ann and first in the hearts of his countrymen," Pope, daughter of Col. Nathaniel Pope, first saw life in the simple countryside of a wealthy landowner living near Mattox Tidewater Virginia. Here, in a land known Creek. Colonel Pope settled his daughter for its many places of serene beauty, few and son-in-law on a 700-acre tract of land scenes impress the senses and mind as do nearby, which was given to them as a those at the birthplace of George Wash- wedding gift. In 1664 John Washington ington. The courage, wholesome char- moved to a new home 4 miles to the east- acter. unselfish devotion, and wise leader- ward on Bridges Creek. ship of the man who was born here will John Washington, his son, Lawrence forever make this a revered historical site Washington, and the later's son, Augus- for all Americans. tine, the great-grandfather, grandfather, and father, respectively, of George all had THE WASHINGTON FAMILY active and distinguished careers as plant. The first Washington ancestor of our ers and civic minded leaders in Virginia first President came to Virginia in 1656. -

Washington and Yorba

GENEALOGY OF THE WASHINGTON AND YORBA AND RELATED FAMILIES OUN1Y C/'.\Llf ORNIP ORA~\G~ . COG .' \CJ.\L SOC\E1)' GtNtJ\L Washington and Related Families - Washington Family Chart I M- Amphillus Twigden 6 Lawrence Washington 001-5. Thomas Washington, b. c. 1605, Margaret (Butler) Washington d. in Spain while a page to Prince Charles (later King Charles II) 1623. 001-1. Robert Washington, b. c. 1589, Unmd. eldest son and heir, d.s.p. 1610 Chart II 001-2. Sir John Washington of Thrapston, d. May 18, 1688. 1 Lawrence Washington M- 1st - Mary Curtis, d. Jan. 1, 1624 or Amphillus (Twigden) Washington 2 25, and bur. at Islip Ch. • M- 2nd - Dorothy Pargiter, d. Oct. 15, 002-1. John Washington, b. in Eng. 1678. 3 1632 or 1633, and emg. to VA c. 1659. He was b. at Warton Co. Lancaster, Eng. 001-3. Sir William Washington of He settled at Bridge's Creek, VA, and d. Packington, b. c. 1594, bur. Jun. 22, Jan. 1677. 1643, St. Martin's m the Field, M- 1st - Anne Pope, dtr of Nathaniel Middlesex Pope of Pope's Creek, VA. M- Anne Villiers 4 M- 2nd - Anne Brett M- 3rd - Ann Gerrard M- 4th - Frances Gerrard Speke Peyton 001-4. Lawrence Washington 5 Appleton 7 1 He was knighted at Newmarkel, Feb. 2 1, 1622 or 23. He 002-2. Lawrence Washington, bap. at and other members of his family often visited Althorpe, the Tring, Co. Hertfordshire, Jun. 18, 1635, home of the Spencers. He is buried in the Parish Ch. -

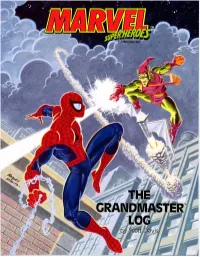

TSR6907.MHR2.Webs-Th

WEBS: The SPIDER-MAN Dossier The GRANDMASTER Log by Scott Davis Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 GRANDMASTER Log Entries …………………………………………………………………………... 3 SPIDER-MAN ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 SPIDER-MAN Supporting Cast ……………………………………………………………………………. 7 SPIDER-MAN Allies ……………………………………………………………………………………… 10 SPIDER-MAN Foes ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 18 An Adventurous Week …………………………………………………………………………………… 56 Set-up ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 56 Timelines …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 58 Future Storyline Tips ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 64 Credits: Design: Scott Davis Art Coordination: Peggy Cooper Editing: Dale A. Donovan Typography: Tracey Zamagne Cover Art: Mark Bagley & John Romita Cartography: Steven Sullivan Interior & Foldup Art: The Marvel Bullpen Design & Production: Paul Hanchette This book is protected under the copyright law of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc. and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. The names of the characters used herein are fictitious and do not refer to any persons living or dead. Any descriptions including similarities to persons living or dead are merely coincidental. Random House and its affiliate companies have worldwide distribution rights in the book trade for English language products of TSR, Inc. Distributed to the book and hobby trade in the United Kingdom by TSR Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL UNIVERSE are trademarks of Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All Marvel characters, character names, and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. 1992 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All Rights Reserved. The TSR logo is a trademark owned by TSR, Inc. 1992 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. TSR, Inc.