Pappus of Alexandria: Book 4 of the Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extending Euclidean Constructions with Dynamic Geometry Software

Proceedings of the 20th Asian Technology Conference in Mathematics (Leshan, China, 2015) Extending Euclidean constructions with dynamic geometry software Alasdair McAndrew [email protected] College of Engineering and Science Victoria University PO Box 18821, Melbourne 8001 Australia Abstract In order to solve cubic equations by Euclidean means, the standard ruler and compass construction tools are insufficient, as was demonstrated by Pierre Wantzel in the 19th century. However, the ancient Greek mathematicians also used another construction method, the neusis, which was a straightedge with two marked points. We show in this article how a neusis construction can be implemented using dynamic geometry software, and give some examples of its use. 1 Introduction Standard Euclidean geometry, as codified by Euclid, permits of two constructions: drawing a straight line between two given points, and constructing a circle with center at one given point, and passing through another. It can be shown that the set of points constructible by these methods form the quadratic closure of the rationals: that is, the set of all points obtainable by any finite sequence of arithmetic operations and the taking of square roots. With the rise of Galois theory, and of field theory generally in the 19th century, it is now known that irreducible cubic equations cannot be solved by these Euclidean methods: so that the \doubling of the cube", and the \trisection of the angle" problems would need further constructions. Doubling the cube requires us to be able to solve the equation x3 − 2 = 0 and trisecting the angle, if it were possible, would enable us to trisect 60◦ (which is con- structible), to obtain 20◦. -

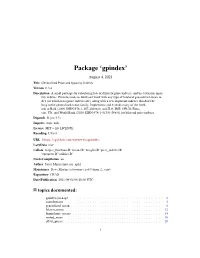

Gpindex: Generalized Price and Quantity Indexes

Package ‘gpindex’ August 4, 2021 Title Generalized Price and Quantity Indexes Version 0.3.4 Description A small package for calculating lots of different price indexes, and by extension quan- tity indexes. Provides tools to build and work with any type of bilateral generalized-mean in- dex (of which most price indexes are), along with a few important indexes that don't be- long to the generalized-mean family. Implements and extends many of the meth- ods in Balk (2008, ISBN:978-1-107-40496-0) and ILO, IMF, OECD, Euro- stat, UN, and World Bank (2020, ISBN:978-1-51354-298-0) for bilateral price indexes. Depends R (>= 3.5) Imports stats, utils License MIT + file LICENSE Encoding UTF-8 URL https://github.com/marberts/gpindex LazyData true Collate 'helper_functions.R' 'means.R' 'weights.R' 'price_indexes.R' 'operators.R' 'utilities.R' NeedsCompilation no Author Steve Martin [aut, cre, cph] Maintainer Steve Martin <[email protected]> Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2021-08-04 06:10:06 UTC R topics documented: gpindex-package . .2 contributions . .3 generalized_mean . .8 lehmer_mean . 12 logarithmic_means . 15 nested_mean . 18 offset_prices . 20 1 2 gpindex-package operators . 22 outliers . 23 price_data . 25 price_index . 26 transform_weights . 33 Index 37 gpindex-package Generalized Price and Quantity Indexes Description A small package for calculating lots of different price indexes, and by extension quantity indexes. Provides tools to build and work with any type of bilateral generalized-mean index (of which most price indexes are), along with a few important indexes that don’t belong to the generalized-mean family. Implements and extends many of the methods in Balk (2008, ISBN:978-1-107-40496-0) and ILO, IMF, OECD, Eurostat, UN, and World Bank (2020, ISBN:978-1-51354-298-0) for bilateral price indexes. -

Plato As "Architectof Science"

Plato as "Architectof Science" LEONID ZHMUD ABSTRACT The figureof the cordialhost of the Academy,who invitedthe mostgifted math- ematiciansand cultivatedpure research, whose keen intellectwas able if not to solve the particularproblem then at least to show the methodfor its solution: this figureis quite familiarto studentsof Greekscience. But was the Academy as such a centerof scientificresearch, and did Plato really set for mathemati- cians and astronomersthe problemsthey shouldstudy and methodsthey should use? Oursources tell aboutPlato's friendship or at leastacquaintance with many brilliantmathematicians of his day (Theodorus,Archytas, Theaetetus), but they were neverhis pupils,rather vice versa- he learnedmuch from them and actively used this knowledgein developinghis philosophy.There is no reliableevidence that Eudoxus,Menaechmus, Dinostratus, Theudius, and others, whom many scholarsunite into the groupof so-called"Academic mathematicians," ever were his pupilsor close associates.Our analysis of therelevant passages (Eratosthenes' Platonicus, Sosigenes ap. Simplicius, Proclus' Catalogue of geometers, and Philodemus'History of the Academy,etc.) shows thatthe very tendencyof por- trayingPlato as the architectof sciencegoes back to the earlyAcademy and is bornout of interpretationsof his dialogues. I Plato's relationship to the exact sciences used to be one of the traditional problems in the history of ancient Greek science and philosophy.' From the nineteenth century on it was examined in various aspects, the most significant of which were the historical, philosophical and methodological. In the last century and at the beginning of this century attention was paid peredominantly, although not exclusively, to the first of these aspects, especially to the questions how great Plato's contribution to specific math- ematical research really was, and how reliable our sources are in ascrib- ing to him particular scientific discoveries. -

AHM As a Measure of Central Tendency of Sex Ratio

Biometrics & Biostatistics International Journal Research Article Open Access AHM as a measure of central tendency of sex ratio Abstract Volume 10 Issue 2 - 2021 In some recent studies, four formulations of average namely Arithmetic-Geometric Mean Dhritikesh Chakrabarty (abbreviated as AGM), Arithmetic-Harmonic Mean (abbreviated as AHM), Geometric- Department of Statistics, Handique Girls’ College, Gauhati Harmonic Mean (abbreviated as GHM) and Arithmetic-Geometric-Harmonic Mean University, India (abbreviated as AGHM) have recently been derived from the three Pythagorean means namely Arithmetic Mean (AM), Geometric Mean (GM) and Harmonic Mean (HM). Each Correspondence: Dhritikesh Chakrabarty, Department of of these four formulations has been found to be a measure of central tendency of data. in Statistics, Handique Girls’ College, Gauhati University, India, addition to the existing measures of central tendency namely AM, GM & HM. This paper Email focuses on the suitability of AHM as a measure of central tendency of numerical data of ratio type along with the evaluation of central tendency of sex ratio namely male-female ratio and female-male ratio of the states in India. Received: May 03, 2021 | Published: May 25, 2021 Keywords: AHM, sex ratio, central tendency, measure Introduction however, involve huge computational tasks. Moreover, these methods may not be able to yield the appropriate value of the parameter if Several research had already been done on developing definitions/ observed data used are of relatively small size (and/or of moderately 1,2 formulations of average, a basic concept used in developing most large size too) In reality, of course, the appropriate value of the 3 of the measures used in analysis of data. -

Astronomy and Hipparchus

CHAPTER 9 Progress in the Sciences: Astronomy and Hipparchus Klaus Geus Introduction Geography in modern times is a term which covers several sub-disciplines like ecology, human geography, economic history, volcanology etc., which all con- cern themselves with “space” or “environment”. In ancient times, the definition of geography was much more limited. Geography aimed at the production of a map of the oikoumene, a geographer was basically a cartographer. The famous scientist Ptolemy defined geography in the first sentence of his Geographical handbook (Geog. 1.1.1) as “imitation through drafting of the entire known part of the earth, including the things which are, generally speaking, connected with it”. In contrast to chorography, geography uses purely “lines and label in order to show the positions of places and general configurations” (Geog. 1.1.5). Therefore, according to Ptolemy, a geographer needs a μέθοδος μαθεματική, abil- ity and competence in mathematical sciences, most prominently astronomy, in order to fulfil his task of drafting a map of the oikoumene. Given this close connection between geography and astronomy, it is not by default that nearly all ancient “geographers” (in the limited sense of the term) stood out also as astronomers and mathematicians: Among them Anaximander, Eudoxus, Eratosthenes, Hipparchus, Poseidonius and Ptolemy are the most illustrious. Apart from certain topics like latitudes, meridians, polar circles etc., ancient geography also took over from astronomy some methods like the determina- tion of the size of the earth or of celestial and terrestrial distances.1 The men- tioned geographers Anaximander, Eudoxus, Hipparchus, Poseidonius and Ptolemy even constructed instruments for measuring, observing and calculat- ing like the gnomon, sundials, skaphe, astrolabe or the meteoroscope.2 1 E.g., Ptolemy (Geog. -

Trisect Angle

HOW TO TRISECT AN ANGLE (Using P-Geometry) (DRAFT: Liable to change) Aaron Sloman School of Computer Science, University of Birmingham (Philosopher in a Computer Science department) NOTE Added 30 Jan 2020 Remarks on angle-trisection without the neusis construction can be found in Freksa et al. (2019) NOTE Added 1 Mar 2015 The discussion of alternative geometries here contrasts with the discussion of the nature of descriptive metaphysics in "Meta-Descriptive Metaphysics: Extending P.F. Strawson’s ’Descriptive Metaphysics’" http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/meta-descriptive-metaphysics.html This document makes connections with the discussion of perception of affordances of various kinds, generalising Gibson’s ideas, in http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/talks/#gibson Talk 93: What’s vision for, and how does it work? From Marr (and earlier) to Gibson and Beyond Some of the ideas are related to perception of impossible objects. http://www.cs.bham.ac.uk/research/projects/cogaff/misc/impossible.html JUMP TO CONTENTS Installed: 26 Feb 2015 Last updated: A very nice geogebra applet demonstrates the method described below: http://www.cut-the-knot.org/pythagoras/archi.shtml. Feb 2017: Added note about my 1962 DPhil thesis 25 Apr 2016: Fixed typo: ODB had been mistyped as ODE (Thanks to Michael Fourman) 29 Oct 2015: Added reference to discussion of perception of impossible objects. 4 Oct 2015: Added reference to article by O’Connor and Robertson. 25 Mar 2015: added (low quality) ’movie’ gif showing arrow rotating. 2 Mar 2015 Formatting problem fixed. 1 Mar 2015 Added draft Table of Contents. -

Some Curves and the Lengths of Their Arcs Amelia Carolina Sparavigna

Some Curves and the Lengths of their Arcs Amelia Carolina Sparavigna To cite this version: Amelia Carolina Sparavigna. Some Curves and the Lengths of their Arcs. 2021. hal-03236909 HAL Id: hal-03236909 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03236909 Preprint submitted on 26 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Some Curves and the Lengths of their Arcs Amelia Carolina Sparavigna Department of Applied Science and Technology Politecnico di Torino Here we consider some problems from the Finkel's solution book, concerning the length of curves. The curves are Cissoid of Diocles, Conchoid of Nicomedes, Lemniscate of Bernoulli, Versiera of Agnesi, Limaçon, Quadratrix, Spiral of Archimedes, Reciprocal or Hyperbolic spiral, the Lituus, Logarithmic spiral, Curve of Pursuit, a curve on the cone and the Loxodrome. The Versiera will be discussed in detail and the link of its name to the Versine function. Torino, 2 May 2021, DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4732881 Here we consider some of the problems propose in the Finkel's solution book, having the full title: A mathematical solution book containing systematic solutions of many of the most difficult problems, Taken from the Leading Authors on Arithmetic and Algebra, Many Problems and Solutions from Geometry, Trigonometry and Calculus, Many Problems and Solutions from the Leading Mathematical Journals of the United States, and Many Original Problems and Solutions. -

Apollonius of Pergaconics. Books One - Seven

APOLLONIUS OF PERGACONICS. BOOKS ONE - SEVEN INTRODUCTION A. Apollonius at Perga Apollonius was born at Perga (Περγα) on the Southern coast of Asia Mi- nor, near the modern Turkish city of Bursa. Little is known about his life before he arrived in Alexandria, where he studied. Certain information about Apollonius’ life in Asia Minor can be obtained from his preface to Book 2 of Conics. The name “Apollonius”(Apollonius) means “devoted to Apollo”, similarly to “Artemius” or “Demetrius” meaning “devoted to Artemis or Demeter”. In the mentioned preface Apollonius writes to Eudemus of Pergamum that he sends him one of the books of Conics via his son also named Apollonius. The coincidence shows that this name was traditional in the family, and in all prob- ability Apollonius’ ancestors were priests of Apollo. Asia Minor during many centuries was for Indo-European tribes a bridge to Europe from their pre-fatherland south of the Caspian Sea. The Indo-European nation living in Asia Minor in 2nd and the beginning of the 1st millennia B.C. was usually called Hittites. Hittites are mentioned in the Bible and in Egyptian papyri. A military leader serving under the Biblical king David was the Hittite Uriah. His wife Bath- sheba, after his death, became the wife of king David and the mother of king Solomon. Hittites had a cuneiform writing analogous to the Babylonian one and hi- eroglyphs analogous to Egyptian ones. The Czech historian Bedrich Hrozny (1879-1952) who has deciphered Hittite cuneiform writing had established that the Hittite language belonged to the Western group of Indo-European languages [Hro]. -

Rethinking Geometrical Exactness Marco Panza

Rethinking geometrical exactness Marco Panza To cite this version: Marco Panza. Rethinking geometrical exactness. Historia Mathematica, Elsevier, 2011, 38 (1), pp.42- 95. halshs-00540004 HAL Id: halshs-00540004 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00540004 Submitted on 25 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Rethinking Geometrical Exactness Marco Panza1 IHPST (CNRS, University of Paris 1, ENS Paris) Abstract A crucial concern of early-modern geometry was that of fixing appropriate norms for de- ciding whether some objects, procedures, or arguments should or should not be allowed in it. According to Bos, this is the exactness concern. I argue that Descartes' way to respond to this concern was to suggest an appropriate conservative extension of Euclid's plane geometry (EPG). In section 1, I outline the exactness concern as, I think, it appeared to Descartes. In section 2, I account for Descartes' views on exactness and for his attitude towards the most common sorts of constructions in classical geometry. I also explain in which sense his geometry can be conceived as a conservative extension of EPG. I con- clude by briefly discussing some structural similarities and differences between Descartes' geometry and EPG. -

MAT 211 Biography Paper & Class Presentation

Name: Spring 2011 Mathematician: Due Date: MAT 211 Biography Paper & Class Presentation “[Worthwhile mathematical] tasks should foster students' sense that mathematics is a changing and evolving domain, one in which ideas grow and develop over time and to which many cultural groups have contributed. Drawing on the history of mathematics can help teachers to portray this idea…” (NCTM, 1991) You have been assigned to write a brief biography of a person who contributed to the development of geometry. Please prepare a one-page report summarizing your findings and prepare an overhead transparency (or Powerpoint document) to guide your 5-minute, in-class presentation. Please use this sheet as your cover page. Include the following sections and use section headers (Who? When? etc.) in your paper. 1. Who? Who is the person you are describing? Provide the full name. 2. When? When did the person live? Be as specific as you can, including dates of birth and death, if available. 3. Where? Where did the person live? Be as specific as you can. If this varied during the person’s lifetime, describe the chronology of the various locations and how they connected to significant life events (birth, childhood, university, work life). 4. What? What did he or she contribute to geometry, mathematics, or other fields? Provide details on topics, well-known theorems, and results. If you discover any interesting anecdotes about the person, or “firsts” that he or she accomplished, include those here. 5. Why? How is this person’s work connected to the geometry we are currently discussing in class? Why was this person’s work historically significant? Include mathematical advances that resulted from this person’s contributions. -

The Function of Diorism in Ancient Greek Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Historia Mathematica 37 (2010) 579–614 www.elsevier.com/locate/yhmat The function of diorism in ancient Greek analysis Ken Saito a, Nathan Sidoli b, a Department of Human Sciences, Osaka Prefecture University, Japan b School of International Liberal Studies, Waseda University, Japan Available online 26 May 2010 Abstract This paper is a contribution to our knowledge of Greek geometric analysis. In particular, we investi- gate the aspect of analysis know as diorism, which treats the conditions, arrangement, and totality of solutions to a given geometric problem, and we claim that diorism must be understood in a broader sense than historians of mathematics have generally admitted. In particular, we show that diorism was a type of mathematical investigation, not only of the limitation of a geometric solution, but also of the total number of solutions and of their arrangement. Because of the logical assumptions made in the analysis, the diorism was necessarily a separate investigation which could only be carried out after the analysis was complete. Ó 2009 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Re´sume´ Cet article vise a` contribuer a` notre compre´hension de l’analyse geometrique grecque. En particulier, nous examinons un aspect de l’analyse de´signe´ par le terme diorisme, qui traite des conditions, de l’arrangement et de la totalite´ des solutions d’un proble`me ge´ome´trique donne´, et nous affirmons que le diorisme doit eˆtre saisi dans un sens plus large que celui pre´ce´demment admis par les historiens des mathe´matiques. -

An Elementary Proof of the Mean Inequalities

Advances in Pure Mathematics, 2013, 3, 331-334 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/apm.2013.33047 Published Online May 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/apm) An Elementary Proof of the Mean Inequalities Ilhan M. Izmirli Department of Statistics, George Mason University, Fairfax, USA Email: [email protected] Received November 24, 2012; revised December 30, 2012; accepted February 3, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ilhan M. Izmirli. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT In this paper we will extend the well-known chain of inequalities involving the Pythagorean means, namely the har- monic, geometric, and arithmetic means to the more refined chain of inequalities by including the logarithmic and iden- tric means using nothing more than basic calculus. Of course, these results are all well-known and several proofs of them and their generalizations have been given. See [1-6] for more information. Our goal here is to present a unified approach and give the proofs as corollaries of one basic theorem. Keywords: Pythagorean Means; Arithmetic Mean; Geometric Mean; Harmonic Mean; Identric Mean; Logarithmic Mean 1. Pythagorean Means 11 11 x HM HM x For a sequence of numbers x xx12,,, xn we will 12 let The geometric mean of two numbers x1 and x2 can n be visualized as the solution of the equation x j AM x,,, x x AM x j1 12 n x GM n 1 n GM x2 1 n GM x12,,, x xnj GM x x j1 1) GM AM HM and 11 2) HM x , n 1 x1 1 HM x12,,, x xn HM x AM x , n 1 1 x1 x j1 j 11 1 3) x xx n2 to denote the well known arithmetic, geometric, and 12 n xx12 xn harmonic means, also called the Pythagorean means This follows because PM .