ΜΕΣΌΤΗΣ in PLATO and ARISTOTLE1 Roberto Grasso

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

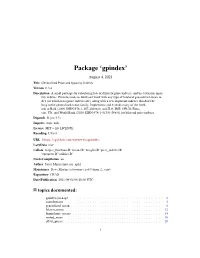

Gpindex: Generalized Price and Quantity Indexes

Package ‘gpindex’ August 4, 2021 Title Generalized Price and Quantity Indexes Version 0.3.4 Description A small package for calculating lots of different price indexes, and by extension quan- tity indexes. Provides tools to build and work with any type of bilateral generalized-mean in- dex (of which most price indexes are), along with a few important indexes that don't be- long to the generalized-mean family. Implements and extends many of the meth- ods in Balk (2008, ISBN:978-1-107-40496-0) and ILO, IMF, OECD, Euro- stat, UN, and World Bank (2020, ISBN:978-1-51354-298-0) for bilateral price indexes. Depends R (>= 3.5) Imports stats, utils License MIT + file LICENSE Encoding UTF-8 URL https://github.com/marberts/gpindex LazyData true Collate 'helper_functions.R' 'means.R' 'weights.R' 'price_indexes.R' 'operators.R' 'utilities.R' NeedsCompilation no Author Steve Martin [aut, cre, cph] Maintainer Steve Martin <[email protected]> Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2021-08-04 06:10:06 UTC R topics documented: gpindex-package . .2 contributions . .3 generalized_mean . .8 lehmer_mean . 12 logarithmic_means . 15 nested_mean . 18 offset_prices . 20 1 2 gpindex-package operators . 22 outliers . 23 price_data . 25 price_index . 26 transform_weights . 33 Index 37 gpindex-package Generalized Price and Quantity Indexes Description A small package for calculating lots of different price indexes, and by extension quantity indexes. Provides tools to build and work with any type of bilateral generalized-mean index (of which most price indexes are), along with a few important indexes that don’t belong to the generalized-mean family. Implements and extends many of the methods in Balk (2008, ISBN:978-1-107-40496-0) and ILO, IMF, OECD, Eurostat, UN, and World Bank (2020, ISBN:978-1-51354-298-0) for bilateral price indexes. -

AHM As a Measure of Central Tendency of Sex Ratio

Biometrics & Biostatistics International Journal Research Article Open Access AHM as a measure of central tendency of sex ratio Abstract Volume 10 Issue 2 - 2021 In some recent studies, four formulations of average namely Arithmetic-Geometric Mean Dhritikesh Chakrabarty (abbreviated as AGM), Arithmetic-Harmonic Mean (abbreviated as AHM), Geometric- Department of Statistics, Handique Girls’ College, Gauhati Harmonic Mean (abbreviated as GHM) and Arithmetic-Geometric-Harmonic Mean University, India (abbreviated as AGHM) have recently been derived from the three Pythagorean means namely Arithmetic Mean (AM), Geometric Mean (GM) and Harmonic Mean (HM). Each Correspondence: Dhritikesh Chakrabarty, Department of of these four formulations has been found to be a measure of central tendency of data. in Statistics, Handique Girls’ College, Gauhati University, India, addition to the existing measures of central tendency namely AM, GM & HM. This paper Email focuses on the suitability of AHM as a measure of central tendency of numerical data of ratio type along with the evaluation of central tendency of sex ratio namely male-female ratio and female-male ratio of the states in India. Received: May 03, 2021 | Published: May 25, 2021 Keywords: AHM, sex ratio, central tendency, measure Introduction however, involve huge computational tasks. Moreover, these methods may not be able to yield the appropriate value of the parameter if Several research had already been done on developing definitions/ observed data used are of relatively small size (and/or of moderately 1,2 formulations of average, a basic concept used in developing most large size too) In reality, of course, the appropriate value of the 3 of the measures used in analysis of data. -

An Elementary Proof of the Mean Inequalities

Advances in Pure Mathematics, 2013, 3, 331-334 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/apm.2013.33047 Published Online May 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/apm) An Elementary Proof of the Mean Inequalities Ilhan M. Izmirli Department of Statistics, George Mason University, Fairfax, USA Email: [email protected] Received November 24, 2012; revised December 30, 2012; accepted February 3, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ilhan M. Izmirli. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT In this paper we will extend the well-known chain of inequalities involving the Pythagorean means, namely the har- monic, geometric, and arithmetic means to the more refined chain of inequalities by including the logarithmic and iden- tric means using nothing more than basic calculus. Of course, these results are all well-known and several proofs of them and their generalizations have been given. See [1-6] for more information. Our goal here is to present a unified approach and give the proofs as corollaries of one basic theorem. Keywords: Pythagorean Means; Arithmetic Mean; Geometric Mean; Harmonic Mean; Identric Mean; Logarithmic Mean 1. Pythagorean Means 11 11 x HM HM x For a sequence of numbers x xx12,,, xn we will 12 let The geometric mean of two numbers x1 and x2 can n be visualized as the solution of the equation x j AM x,,, x x AM x j1 12 n x GM n 1 n GM x2 1 n GM x12,,, x xnj GM x x j1 1) GM AM HM and 11 2) HM x , n 1 x1 1 HM x12,,, x xn HM x AM x , n 1 1 x1 x j1 j 11 1 3) x xx n2 to denote the well known arithmetic, geometric, and 12 n xx12 xn harmonic means, also called the Pythagorean means This follows because PM . -

Pappus of Alexandria: Book 4 of the Collection

Pappus of Alexandria: Book 4 of the Collection For other titles published in this series, go to http://www.springer.com/series/4142 Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences Managing Editor J.Z. Buchwald Associate Editors J.L. Berggren and J. Lützen Advisory Board C. Fraser, T. Sauer, A. Shapiro Pappus of Alexandria: Book 4 of the Collection Edited With Translation and Commentary by Heike Sefrin-Weis Heike Sefrin-Weis Department of Philosophy University of South Carolina Columbia SC USA [email protected] Sources Managing Editor: Jed Z. Buchwald California Institute of Technology Division of the Humanities and Social Sciences MC 101–40 Pasadena, CA 91125 USA Associate Editors: J.L. Berggren Jesper Lützen Simon Fraser University University of Copenhagen Department of Mathematics Institute of Mathematics University Drive 8888 Universitetsparken 5 V5A 1S6 Burnaby, BC 2100 Koebenhaven Canada Denmark ISBN 978-1-84996-004-5 e-ISBN 978-1-84996-005-2 DOI 10.1007/978-1-84996-005-2 Springer London Dordrecht Heidelberg New York British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2009942260 Mathematics Classification Number (2010) 00A05, 00A30, 03A05, 01A05, 01A20, 01A85, 03-03, 51-03 and 97-03 © Springer-Verlag London Limited 2010 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licenses issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. -

The Pythagorean Theorem Crown Jewel of Mathematics

The Pythagorean Theorem Crown Jewel of Mathematics 5 3 4 John C. Sparks The Pythagorean Theorem Crown Jewel of Mathematics By John C. Sparks The Pythagorean Theorem Crown Jewel of Mathematics Copyright © 2008 John C. Sparks All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form—except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review—without permission in writing from the author or publisher. Front cover, Pythagorean Dreams, a composite mosaic of historical Pythagorean proofs. Back cover photo by Curtis Sparks ISBN: XXXXXXXXX First Published by Author House XXXXX Library of Congress Control Number XXXXXXXX Published by AuthorHouse 1663 Liberty Drive, Suite 200 Bloomington, Indiana 47403 (800)839-8640 www.authorhouse.com Produced by Sparrow-Hawke †reasures Xenia, Ohio 45385 Printed in the United States of America 2 Dedication I would like to dedicate The Pythagorean Theorem to: Carolyn Sparks, my wife, best friend, and life partner for 40 years; our two grown sons, Robert and Curtis; My father, Roscoe C. Sparks (1910-1994). From Earth with Love Do you remember, as do I, When Neil walked, as so did we, On a calm and sun-lit sea One July, Tranquillity, Filled with dreams and futures? For in that month of long ago, Lofty visions raptured all Moonstruck with that starry call From life beyond this earthen ball... Not wedded to its surface. But marriage is of dust to dust Where seasoned limbs reclaim the ground Though passing thoughts still fly around Supernal realms never found On the planet of our birth. And I, a man, love you true, Love as God had made it so, Not angel rust when then aglow, But coupled here, now rib to soul, Dear Carolyn of mine. -

Pappus of Alexandria: Book 4 of the Collection

Pappus of Alexandria: Book 4 of the Collection For other titles published in this series, go to http://www.springer.com/series/4142 Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences Managing Editor J.Z. Buchwald Associate Editors J.L. Berggren and J. Lützen Advisory Board C. Fraser, T. Sauer, A. Shapiro Pappus of Alexandria: Book 4 of the Collection Edited With Translation and Commentary by Heike Sefrin-Weis Heike Sefrin-Weis Department of Philosophy University of South Carolina Columbia SC USA [email protected] Sources Managing Editor: Jed Z. Buchwald California Institute of Technology Division of the Humanities and Social Sciences MC 101–40 Pasadena, CA 91125 USA Associate Editors: J.L. Berggren Jesper Lützen Simon Fraser University University of Copenhagen Department of Mathematics Institute of Mathematics University Drive 8888 Universitetsparken 5 V5A 1S6 Burnaby, BC 2100 Koebenhaven Canada Denmark ISBN 978-1-84996-004-5 e-ISBN 978-1-84996-005-2 DOI 10.1007/978-1-84996-005-2 Springer London Dordrecht Heidelberg New York British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2009942260 Mathematics Classification Number (2010) 00A05, 00A30, 03A05, 01A05, 01A20, 01A85, 03-03, 51-03 and 97-03 © Springer-Verlag London Limited 2010 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licenses issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. -

Four Formulations of Average Derived from Pythagorean Means

International Journal of Mathematics Trends and Technology Volume 67 Issue 6, 97-118, June, 2021 ISSN: 2231 – 5373 /doi:10.14445/22315373/IJMTT-V67I6P512 © 2021 Seventh Sense Research Group® Four Formulations of Average Derived from Pythagorean Means Dhritikesh Chakrabarty Department of Statistics, Handique Girls’ College, Gauhati University, Guwahati – 781001, Assam, India. Abstract: Four definitions / formulations of average termed here as Arithmetic-Geometric Mean (abbreviated as AGM), Arithmetic- Harmonic Mean (abbreviated as AHM), Geometric-Harmonic Mean (abbreviated as GHM) and Arithmetic-Geometric- Harmonic (abbreviated as Mean AGHM) respectively have been derived / developed from the three Pythagorean means namely arithmetic mean (abbreviated as Mean AM), geometric mean (abbreviated as Mean GM) and harmonic mean (abbreviated as Mean HM) with an objective of developing of more accurate measures of central tendency of data. The derivations of these four formulations of average, with numerical examples, have been presented in this paper. Key Words: AGM, AHM, GHM, AGHM, Formulation of Average. 1. Introduction Average [1] is a concept which describes any characteristic of an aggregate / population / class of individuals overall but not of an individual in the aggregate / population / class in particular. It is used in most of the measures associated to data (or list of numerical values). Pythagoras [2] , [4] , one exponent of mathematics, is the pioneer of defining average. He defined the three most common averages namely arithmetic mean, geometric mean and harmonic mean which were given the name “Pythagorean Means” [4] , [16] , [35] , [37] as a mark of honor to him. Later on, a number of definitions / formulations of average had been derived due to necessity of handling different situations (different types of data) some of which are Quadratic Mean Square Root Mean , Cubic Mean , Cube Root Mean , Generalized p Mean & Generalized pth Root Mean etc. -

Stability of Pythagorean Mean Functional Equation P.Narasimman 1 , K

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Global Journal of Mathematics Vol. 4, No. 1, September provided29, 2015 by Repositório Comum www.gpcpublishing.com ISSN: 2395-4760 Stability of Pythagorean Mean Functional Equation P.Narasimman 1 , K. Ravi 2 , Sandra Pinelas 3 1 Department of Mathematics, Thiruvalluvar University College of Arts and Science,Gajalnaickanpatti, Tirupattur-635 901, TamilNadu, India. 2 Department of Mathematics, Sacred Heart College,Tirupattur-635 601, TamilNadu, India 3 Academia Militar, Departamento de Ciências Exactas e Naturais, Av.Conde Castro Guimarães, 2720-113 Amadora, Portugal Abstracts: In this paper, authors introduce a new Pythagorean mean functional equation which relates the three classical Pythagorean mean and investigate its generalized Hyers -Ulam stability. Also, Motivated by the work of Roman Ger [7], we deal with the general solution of Pythagorean means functional equation. We also provide counter -examples for singular cases. Very specially in this paper we illustrate the geometrical interpretation and application of new introduced Pythagorean mean functional equation. Key words and phrases:Pythagorean Means, Arithmetic mean, Geometric mean and Harmonic mean, Generalized Hyers-Ulam stability. 2010 Mathematics Subject Cla ssi fication: 39B52, 39B62, 39B72, 39B82. 1.Introduction There is a legend that one day when Pythagoras (c.500 BCE) was passing a blacksmith’s shop, he heard harmonious music ringing from the hammers. When he enquired, he was told that the weights of the hammers were 6, 8, 9, and 12 pounds. These ratios produce a fundamental and its fourth, fifth and octave. This was evidence that the elegance of mathematics is manifested in the harmony of nature. -

HISTORY of MATH CONCEPTS Essentials, Images and Memes

HISTORY OF MATH CONCEPTS Essentials, Images and Memes Sergey Finashin Modern Mathematics having roots in ancient Egypt and Babylonia, really flourished in ancient Greece. It is remarkable in Arithmetic (Number theory) and Deductive Geometry. Mathematics written in ancient Greek was translated into Arabic, together with some mathematics of India. Mathematicians of Islamic Middle East significantly developed Algebra. Later some of this mathematics was translated into Latin and became the mathematics of Western Europe. Over a period of several hundred years, it became the mathematics of the world. Some significant mathematics was also developed in other regions, such as China, southern India, and other places, but it had no such a great influence on the international mathematics. The most significant for development in mathematics was giving it firm logical foundations in ancient Greece which was culminated in Euclid’s Elements, a masterpiece establishing standards of rigorous presentation of proofs that influenced mathematics for many centuries till 19th. Content 1. Prehistory: from primitive counting to numeral systems 2. Archaic mathematics in Mesopotamia (Babylonia) and Egypt 3. Birth of Mathematics as a deductive science in Greece: Thales and Pythagoras 4. Important developments of ideas in the classical period, paradoxes of Zeno 5. Academy of Plato and his circle, development of Logic by Aristotle 6. Hellenistic Golden Age period, Euclid of Alexandria 7. Euclid’s Elements and its role in the history of Mathematics 8. Archimedes, Eratosthenes 9. Curves in the Greek Geometry, Apollonius the Great Geometer 10. Trigonometry and astronomy: Hipparchus and Ptolemy 11. Mathematics in the late Hellenistic period 12. Mathematics in China and India 13. -

Universal Equations for Pythagorean and Sauter-Type Formulas of Mean Value Calculation and Classification of the Extended Pythagorean Means

Mining Science Mining Science, vol. 24, 2017, 227–235 (Previously Prace Naukowe Instytutu Gornictwa Politechniki Wroclawskiej, ISSN 0370-0798) ISSN 2300-9586 (print) www.miningscience.pwr.edu.pl ISSN 2353-5423 (online) Received May 6, 2016; reviewed; accepted September 19, 2017 UNIVERSAL EQUATIONS FOR PYTHAGOREAN AND SAUTER-TYPE FORMULAS OF MEAN VALUE CALCULATION AND CLASSIFICATION OF THE EXTENDED PYTHAGOREAN MEANS Jan DRZYMAŁA* Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, Laboratory of Mineral Processing, Wybrzeze Wyspian- skiego 27, 50-370 Wroclaw Abstract: A general equation, combining the Pythagorean and Sauter-type formulas, which can be used for calculation of a mean of a set of values is given and discussed in the paper. A classification of means, forming the Extended Pythagorean Means family, including power (arithmetic, geometric, quadratic, cubic, etc.), inverted power (harmonic, inverted quadratic, inverted cubic, etc.), and Sauter-type (volume- surface, volume-length, etc.) is presented. The calculated means, depending on their type, are different. Formulas for calculating mean values for a set of values treated individually, in groups and as a fraction (weighted mean) are also given. Keywords: average value, mean size, mean diameter, weighted mean 1. INTRODUCTION In very often there is a need for calculation of the mean value, especially when one deals with poly-dispersed in property particles, air bubbles and droplets. In such a situation, there is a question which formula should be chosen for the mean value calculation. The possible number of formulas of mean size is great (theoretically infi- nite) (Bullen 1990; 2003). However, it can be significantly narrowed to the so-called Pythagorean and Sauter-type means, which are simple, universal, meaningful and used _________ * Corresponding author: [email protected] (J. -

Origin of Irrational Numbers and Their Approximations

computation Review Origin of Irrational Numbers and Their Approximations Ravi P. Agarwal 1,* and Hans Agarwal 2 1 Department of Mathematics, Texas A&M University-Kingsville, 700 University Blvd., Kingsville, TX 78363, USA 2 749 Wyeth Street, Melbourne, FL 32904, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In this article a sincere effort has been made to address the origin of the incommensu- rability/irrationality of numbers. It is folklore that the starting point was several unsuccessful geometric attempts to compute the exact values of p2 and p. Ancient records substantiate that more than 5000 years back Vedic Ascetics were successful in approximating these numbers in terms of rational numbers and used these approximations for ritual sacrifices, they also indicated clearly that these numbers are incommensurable. Since then research continues for the known as well as unknown/expected irrational numbers, and their computation to trillions of decimal places. For the advancement of this broad mathematical field we shall chronologically show that each continent of the world has contributed. We genuinely hope students and teachers of mathematics will also be benefited with this article. Keywords: irrational numbers; transcendental numbers; rational approximations; history AMS Subject Classification: 01A05; 01A11; 01A32; 11-02; 65-03 Citation: Agarwal, R.P.; Agarwal, H. 1. Introduction Origin of Irrational Numbers and Their Approximations. Computation Almost from the last 2500 years philosophers have been unsuccessful in providing 2021, 9, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/ satisfactory answer to the question “What is a Number”? The numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, , have ··· computation9030029 been called as natural numbers or positive integers because it is generally perceived that they have in some philosophical sense a natural existence independent of man. -

1. the Place of the Republic in the Neoplatonic Commentary Tradition

1. The place of the Republic in the Neoplatonic commentary tradition If you asked a random philosopher of the 20th or 21st century ‘What is Plato’s most important book?’ we think he or she would reply ‘The Republic, of course.’ Thanks to the Open Syllabus Project we don’t need to rely on mere speculation to intuit professional philosophy’s judgement on this matter.1 We can see what book by Plato professional philosophers put on the reading lists for their students. The Open Syllabus Project surveyed over a million syllabi for courses in English-speaking universities. Filtering the results by discipline yields the result that only two texts were assigned more frequently for subjects in Philosophy (that is, Philosophy subjects generally– not merely subjects on the history of Philosophy). Plato’s Republic comes third after Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and John Stuart Mill’s Utilitarianism. If you remove the filter for discipline, then Plato’s Republic is the second- most assigned text in university studies in the English-speaking world, behind only Strunk and White’s Elements of Style.2 Thus graduates of English-language universities in our time and place are more likely to be acquainted with a work of philosophy than they are to be acquainted with any of the works of Shakespeare and the philosophical text through which they are likely to be acquainted with the discipline is Plato’s Republic. For us, it is Plato’s greatest work and certainly among the greatest works of Philosophy ever. Philosophers and other university academics might be surprised to learn that their judgement was not the judgement of antiquity.