An Exegetical Analysis of Numbers 31: 27 As a Panacea for Resource Control Agitation in Niger Delta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immorality on the Border Lesson #11 for December 12, 2009 Scriptures: Numbers 25; 31; Deuteronomy 21:10-14; 1 Corinthians 10:1-14; Revelation 2:14

People on the Move: The Book of Numbers Immorality on the Border Lesson #11 for December 12, 2009 Scriptures: Numbers 25; 31; Deuteronomy 21:10-14; 1 Corinthians 10:1-14; Revelation 2:14. 1. This lesson is a discussion about the disastrous results of Balaam’s work with the people of Midian and Moab and the seduction of the children of Israel leading to the death of 24,000 Israelites. It is a lesson about things that “nice people” do not talk about. 2. By the time of the “encounter” with Balaam, the children of Israel–who forty years earlier had been frightened terribly by the report of the ten spies–had seen God work with their soldiers in conquering three nations and were resting at ease in the small plain east of the Jordan River where they could look across the river and see Jericho a few miles away. 3. What were they waiting for? Was Moses busy writing the book of Deuteronomy–a summary of three sermons that Moses was asked to give to the children of Israel? Were they working out the details of the division of the land of Canaan? How did they divide up a land that none of them–except for the parts that Caleb and Joshua had “spied out”–had ever seen? They had no pictures and no maps. They had only what God may have shown Moses. Surely, God understood the hazard that was present in that setting of idleness. Why do you think He allowed them to camp there for some time? They were camped in a small flat area below the hills of Moab. -

Hebrew 7602 AU17.Pdf

Attention! This is a representative syllabus. The syllabus for the course you are enrolled in will likely be different. Please refer to your instructor’s syllabus for more information on specific requirements for a given semester. HEBREW 7602 STUDIES IN HEBREW PROSE: THE PROBLEM OF EVIL IN BIBLICAL & POST-BIBLICAL HEBREW LITERATURE Autumn 2017 Meeting Time/Location Instructor: Office Hours: Phone: Email: Class will not meet on September 21 and October 5 DESCRIPTION: If there is a God, and He is all-powerful, all-knowing, and wholly benevolent, how can evil exist? The BibLe raises this question — the problem of evil — many times in different contexts and ways. Through extensive reading in primary and secondary sources relating to theodicies, students wilL gain an appreciation of religious thought among the ancient Israelites and their Near Eastern neighbors as well as later Jewish approaches to theodicy. All readings will be done in Hebrew, but use of English Bibles outside of class is permitted. OBJECTIVES: 1. to introduce students to the problem of evil in the Hebrew BibLe and certain postbiblical texts. 2. to acquaint students with the ancient contexts in which Jewish theodicies developed. 3. to familiarize students with key scholarly discussions of the subject. 4. to develop students’ facility with reading and analyzing biblical Hebrew prose. CLASSWORK: 1. Students are expected to attend aLL classes. In the event of absence, pLease contact other students for material covered in class. Please notify the instructor in advance of any unavoidable absences. 2. Students are expected to participate in class. 3. Students are expected to arrive punctuaLLy for class. -

Parshat Matot/Masei

Parshat Matot/Masei A free excerpt from the Kehot Publication Society's Chumash Bemidbar/Book of Numbers with commentary based on the works of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, produced by Chabad of California. The full volume is available for purchase at www.kehot.com. For personal use only. All rights reserved. The right to reproduce this book or portions thereof, in any form, requires permission in writing from Chabad of California, Inc. THE TORAH - CHUMASH BEMIDBAR WITH AN INTERPOLATED ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY BASED ON THE WORKS OF THE LUBAVITCHER REBBE Copyright © 2006-2009 by Chabad of California THE TORAHSecond,- revisedCHUMASH printingB 2009EMIDBAR WITH AN INTERPOLATED ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARYA BprojectASED ON of THE WORKS OF ChabadTHE LUBAVITCH of CaliforniaREBBE 741 Gayley Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90024 310-208-7511Copyright / Fax © 310-208-58112004 by ChabadPublished of California, by Inc. Kehot Publication Society 770 Eastern Parkway,Published Brooklyn, by New York 11213 Kehot718-774-4000 Publication / Fax 718-774-2718 Society 770 Eastern Parkway,[email protected] Brooklyn, New York 11213 718-774-4000 / Fax 718-774-2718 Order Department: 291 KingstonOrder Avenue, Department: Brooklyn, New York 11213 291 Kingston718-778-0226 Avenue / /Brooklyn, Fax 718-778-4148 New York 11213 718-778-0226www.kehot.com / Fax 718-778-4148 www.kehotonline.com All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book All rightsor portions reserved, thereof, including in any the form, right without to reproduce permission, this book or portionsin writing, thereof, from in anyChabad form, of without California, permission, Inc. in writing, from Chabad of California, Inc. The Kehot logo is a trademark ofThe Merkos Kehot L’Inyonei logo is a Chinuch,trademark Inc. -

Lesson 5: the Book of Numbers

UCF Tuesday Night Bible Study UCF - Tuesday Night Bible St... Page 1 of 6 Lesson 5: The Book of Numbers Numbers covers about 38 years of desert wandering by the Israelites. It is called Numbers because it includes two numberings of the men of war, in chapters 1-4 and 26-27. The first numbering was made the second year after the Israelites left Egypt. Then, with Judah leading the way, each tribe was given a position in the march to Canaan. From this point on, Numbers is a wilderness book. It describes the failure of Israel at Kadesh-Barnea and their wilderness wanderings until the unbelieving generation died, after which the second numbering took place. This book has been described as the "longest funeral march in history." An interesting fact to note is the nation of Israel did not grow during its wilderness wanderings. In fact, they declined in number by almost 2,000 men of war. Thus, they wasted 38 years, suffered unnecessary afflictions, and did not grow numerically. This is what unbelief does to the Christian; it produces wasted time, wasted effort, and spiritual stalemate. Numbers has many spiritual lessons for us today, as explained in Hebrews 3-4 and 1 Corinthians 10:6-10. Read the passage in 1 Corinthians, and explain what it says the book of Numbers should teach us today: Brief Outline of the Book: I. Preparations for the Wilderness (1:1-10:10) II. Wanderings (10:11-21:35) III. The Balaam Incident (chps. 22-25) IV. Preparations To Enter Canaan (chps. -

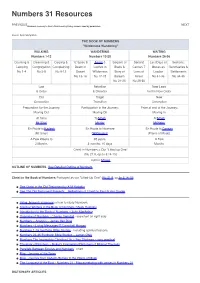

Numbers 31 Resources

Numbers 31 Resources PREVIOUSNumbers: Journey to God's Rest-Land by Irving Jensen- used by permission NEXT Source: Ryrie Study Bible THE BOOK OF NUMBERS "Wilderness Wandering" WALKING WANDERING WAITING Numbers 1-12 Numbers 13-25 Numbers 26-36 Counting & Cleansing & Carping & 12 Spies & Aaron & Serpent of Second Last Days of Sections, Camping Congregation Complaining Death in Levites in Brass & Census 7 Moses as Sanctuaries & Nu 1-4 Nu 5-8 Nu 9-12 Desert Wilderness Story of Laws of Leader Settlements Nu 13-16 Nu 17-18 Balaam Israel Nu 31-33 Nu 34-36 Nu 21-25 Nu 26-30 Law Rebellion New Laws & Order & Disorder for the New Order Old Tragic New Generation Transition Generation Preparation for the Journey: Participation in the Journey: Prize at end of the Journey: Moving Out Moving On Moving In At Sinai To Moab At Moab Mt Sinai Mt Hor Mt Nebo En Route to Kadesh En Route to Nowhere En Route to Canaan (Mt Sinai) (Wilderness) (Plains of Moab) A Few Weeks to 38 years, A Few 2 Months 3 months, 10 days Months Christ in Numbers = Our "Lifted-up One" (Nu 21:9, cp Jn 3:14-15) Author: Moses OUTLINE OF NUMBERS- See Detailed Outline of Numbers Christ in the Book of Numbers: Portrayed as our "Lifted-Up One" (Nu 21:9, cp Jn 3:14-15) See Christ in the Old Testament by A M Hodgkin See The Old Testament Presents... Reflections of Christ by Paul R Van Gorder Irving Jensen's summaryon how to study Numbers Spiritual Warfare in the Book of Numbers-Chuck Huckaby Introduction to the Book of Numbers – John MacArthur Overview of Numbers - Charles Swindoll - see chart -

Book Study – the Torah

Book Study – The Torah A tool to help with reading the Bible. Produced by XA Denton Chi Alpha | UNT & TWU Introduction: In the first book of the Torah, Genesis, we see God create a good and perfect world. Included in His creation was mankind, which was to act as God's representatives on earth. Mankind, however, had other ideas and chose to define what was good and evil for themselves. After this decision, things get bad for mankind – so bad that God has to eventually destroy them all with the flood and start over. This represents the beginning of God's mission to rescue and restore His world. To begin this mission, God raises up Abraham and promises him that through his descendants all of the nations of the world would come to know God's blessing. It turns out, though, that Abraham and his descendants were a pretty dysfunctional family. However, in spite of their mishaps, God still continues to use them for His plan. This brings us to the second book of the Torah, Exodus. Here, the Israelites are enslaved to the Egyptians, and the first half of the book focuses on how God raises up Moses to deliver His people from the Egyptians. God saves His people from the Egyptians, but now they are a nation without a home, wandering in the desert and unsure why God saved them in the first place. From this point forward, we see God begin to try and restore His presence among His People. He comes down on Mount Sinai, gives Moses the Ten Commandments, and gives instructions on how the Israelites should build a temple – a place where God will be able to live among them. -

Numbers 25 Commentary

Numbers 25 Commentary PREVIOUSNumbers: Journey to God's Rest-Land by Irving Jensen- used by permission NEXT Source: Ryrie Study Bible THE BOOK OF NUMBERS "Wilderness Wandering" WALKING WANDERING WAITING Numbers 1-12 Numbers 13-25 Numbers 26-36 Counting & Cleansing & Carping & 12 Spies & Aaron & Serpent of Second Last Days of Sections, Camping Congregation Complaining Death in Levites in Brass & Census 7 Moses as Sanctuaries & Nu 1-4 Nu 5-8 Nu 9-12 Desert Wilderness Story of Laws of Leader Settlements Nu 13-16 Nu 17-18 Balaam Israel Nu 31-33 Nu 34-36 Nu 21-25 Nu 26-30 Law Rebellion New Laws & Order & Disorder for the New Order Old Tragic New Generation Transition Generation Preparation for the Journey: Participation in the Journey: Prize at end of the Journey: Moving Out Moving On Moving In At Sinai To Moab At Moab Mt Sinai Mt Hor Mt Nebo En Route to Kadesh En Route to Nowhere En Route to Canaan (Mt Sinai) (Wilderness) (Plains of Moab) A Few Weeks to 38 years, A Few 2 Months 3 months, 10 days Months Christ in Numbers = Our "Lifted-up One" (Nu 21:9, cp Jn 3:14-15) Author: Moses Numbers 25:1 While Israel remained at Shittim, the people began to play the harlot with the daughters of Moab. Greek (Septuagint) kai katelusen (3SAAI: refresh oneself, lodge Lu 9:12;Ge 24:23 travelers loosening their own burdens when they stayed at a house on a journey) Israel en Sattin kai ebebelothe (3SAPI: bebeloo: cause to become unclean, profane, or ritually unacceptable - defile, profane.’disregarding what is to be kept sacred or holy: Mt12:5) ho laos ekporneusai (AAN: ekporneuo: indulged in flagrant immorality: see Jude 1:7) eis tas thugateras (daughters: Mt9:18) Moab Amplified ISRAEL SETTLED down and remained in Shittim, and the people began to play the harlot with the daughters of Moab, BGT Numbers 25:1 κα κατλυσεν Ισραηλ ν Σαττιν κα βεβηλθη λας κπορνεσαι ες τς θυγατρας Μωαβ NET Numbers 25:1 When Israel lived in Shittim, the people began to commit sexual immorality with the daughters of Moab. -

The Torah: a Women's Commentary

STUDY GUIDE The Torah: A Women’s Commentary Parashat Balak NUMBERS 22:2-25:9 Study Guide written by Rabbi Stephanie Bernstein Dr. Tamara Cohn Eskenazi, Dr. Lisa D. Grant, and Rabbi Andrea L. Weiss, Ph.D., editors Rabbi Hara E. Person, series editor Parashat Balak Study Guide Themes Theme 1: The Seer Balaam—Have Vision Will Travel Theme 2: It’s a Slippery Slope—the Dangers of Foreign Women INTRODUCTION n Parashat Balak the Israelites are camped on the plains of Moab, ready Ito enter Canaan. In the midst of their final preparations to enter the land God promised to their ancestors, yet another obstacle emerges. Balak, king of Moab, grows concerned about the fierce reputation of the Israelites, which he observed in the Israelites’ encounter with the Amorites (Numbers 21:21–32). Balak’s subjects worry that the Israelites, due to their large numbers, will devour the resources of Moab. In response, Balak hires a well-known seer named Balaam to curse the Israelites, thus reflecting the widely held belief in the ancient world that putting a curse on someone was an effective means of subduing an enemy. The standoff between the powers of the God of Israel and those of a foreign seer proves to be no contest. Even Balaam’s talking female donkey, who represents the biblical ideal of wisdom, recognizes the efficacy of God’s power—unlike her human master, the professional seer. Although hired to curse the Israelites, Balaam ends up blessing them instead. In a series of four oracles, Balaam ultimately does the opposite of what Balak desires and establishes that the power of Israel’s God is greater than even the most skilled human seers. -

Discussion Questions

The Book of Numbers Reflection and Discussion Questions Numbers 1: The Levities were given a specific calling to care for the tabernacle. God gives each of us a specific calling as well. What has He called you to do for Him? Numbers 2: The children of Israel obeyed what the Lord said, they followed his direction, even with where to sleep! What direction has God given you that may not seem important or make sense right now but you must follow? Numbers 3: God gave specific instructions throughout His Word that must be obeyed. If we are not obedient there will be consequences. How have you know this to be true in your life? Numbers 4: Sometimes the tasks God calls us to are a burden. They can be difficult to bear. How have you been obedient to God when the task seemed like too much of a burden to carry? Numbers 5: Sin is always found out, for we cannot hide anything from God. We must confess our sins to the Lord in order to keep our relationship with Him growing. What is hindering you from drawing near to Him today? Numbers 6: The Lord desires to bless His people. What blessings have clearly been given to you from God? Numbers 7: God asks every child of His to keep Him first, to obey Him above all and to give Him the honor and glory due to Him. How does this truth help you in your personal Christian walk? 1 Numbers 8: All that belongs to God must be set apart and cleansed. -

Pinchas and the Next Generation Rabbi Jonathan Ziring: [email protected]

Pinchas and the Next Generation Rabbi Jonathan Ziring: [email protected] Our own worst enemies – what was seen by Bilaam vs. what is seen by Moshe 1. Numbers 24:3, 5 )ג(ַוִּיָׁשָּׂ֥אְ מָׁשֹל֖וַ וֹיַאמַ֑ר ְנ אֻ֤ם ִּבְלָׁעם֙ ְבֹנ֣ו ְבֹעֹ֔ר ּוְנ אָּׂ֥ם ַה ֶ֖גֶבר ְש ָּׂ֥תם ָׁה ָָֽׁעִּין׃… )ה(ַמ ָֹּׂ֥ה־טבּוֹ אָׁה ֶ֖ליָך ַיֲע ַֹ֑קבִּ מְשְכֹנ ֶ֖תיָך ִּיְשָׁר ָֽ אל׃ (3) Taking up his theme, he said: Word of Balaam son of Beor, Word of the man whose eye is true,… (5) How fair are your tents, O Jacob, Your dwellings, O Israel! 2. Numbers 25 )א(ַוָּׂ֥יֶשב ִּיְשָׁר א֖לַבִּש ִַּ֑טיםַ וָׁיֶ֣חל ָׁהָׁעִֹּ֔םלְזנֹ֖ותֶ אל־ְבֹנָּׂ֥ותֹ מו ָָֽׁאב׃ )ב(ַ וִּתְקֶר֣אןָָׁׁ לָׁעְֹ֔םלִּזְב ֖חי אֱֹלהיֶַ֑הןַוֹ֣יַאכל ָׁה ָֹׁ֔עםַו ִָּֽיְשַתֲחּו֖ ָֽ ּו לאֹל הי ֶָֽהן׃ )ג(ַ וִּיָׁצֶָּׂ֥מד ִּיְשָׁר א֖ל ְלַבַ֣עלְפֹעַ֑ורַו ִָּֽיַחר־ַאָּׂ֥ף ה'ְבִּיְשָׁר ָֽ אל׃ )ד(ַ וֹיֶֹּ֨אמר ה'ֶ אֹל־מ ֶֶׁ֗שה ַקַ֚חֶ אתָׁ־כל־ָׁרא ֣שי ָׁה ָֹׁ֔עםְ וֹהוַקָּׂ֥עֹאו ָׁתַָ֛ם לה' ֶ֣נֶגד ַה ַָׁ֑שֶמשְ וָׁי ָֹ֛שבֲ חרָּׂ֥ ֹון ַאף־ה'ִּ מִּיְשָׁר ָֽ אל׃ )ה( ַוֹיֶ֣אמרֹמֶֹ֔שהֶ אל־ֹשְפ ֖טי ִּיְשָׁר אַ֑ל ִּהְרגּו֙ ִּ֣ אישֲ אָׁנ ָֹׁ֔שיו ַהִּנְצָׁמ ִּ֖דְים לַבַָּׂ֥על ְפָֽעֹור׃ )ו(ְ וִּהֵּ֡נהִּ אישׁ֩ ִּמְבֹּ֨ני ִּיְשָׁר אֵ֜ל ָׁבֶׁ֗אַ וַיְק ֻ֤רבֶ אֶל־אָׁחיוֶ֙ ל את־ַהִּמְדָׁיִּנְֹ֔יתעי ֣ניֹ מֶֹ֔שה ּולְע ֖ינ ָׁיכל־ֲעַד֣תְב ני־ִּיְשָׁר אַ֑לְ ו הָׁ֣מה ֹב ִֹּ֔כים ֶ֖פַתח ָֹּׂ֥ אֶהלֹ מו ָֽ עד׃ )ז(ַ וַיְֶׁ֗רא ִָּֽפיְנָׁחס֙ ֶבֶן־אְלָׁעָׁזֹ֔ר ֶָֽבן־ַא ֲהֹ֖רןַהֹכַ֑הןַו ָׁ֙יָׁקםִּ֙ מֹת֣וְך ָָֽׁהע ָֹׁ֔דהַ וִּיַקָֹּׂ֥ח רַ֖מח ְבָׁיָֽדֹו׃ )ח( ַַ֠ וָׁיֹבא ַַאחֹּ֨ר ִָּֽאיש־ִּיְשָׁר אֵ֜ל ֶאל־ַה ק ֶָׁׁ֗בהַוִּיְדֹקרֶ֙את־ְש ני -

A Pilgrimage Through the Old Testament

A PILGRIMAGE THROUGH THE OLD TESTAMENT ** Year 1 of 3 ** Cold Harbor Road Church Of Christ Mechanicsville, Virginia Old Testament Curriculum TABLE OF CONTENTS Lesson 1: INTRODUCTION TO THE OLD TESTAMENT Overview of Old Testament .........................................................................5 Lesson 2: CREATION Genesis 1 ........................................................................................................10 Lesson 3: ADAM AND EVE Genesis 2 ........................................................................................................14 Lesson 4: THE GARDEN OF EDEN Genesis 3 ........................................................................................................16 Lesson 5: CAIN AND ABEL Genesis 4,5......................................................................................................19 Lesson 6: NOAH FOUND GRACE IN THE EYES OF THE LORD Genesis 6,7......................................................................................................23 Lesson 7: GOD MAKES A PROMISE TO NOAH Genesis 8,9......................................................................................................26 Lesson 8: THE TOWER OF BABEL Genesis 10,11..................................................................................................29 Lesson 9: THE CALL OF ABRAHAM Genesis 12 ......................................................................................................33 Lesson 10: ABRAHAM AND LOT Genesis 13,14..................................................................................................37 -

One More Wilderness Story: Balaam

One More Wilderness Story: Balaam Image from: www.flickr.com from: Image Balaam’s Spiritual Victory Image from: www.flickr.com from: Image o Balaam receives an invitation from Balak. Numbers 22:2-8 [2] Now Balak the son of Zippor saw all that Israel had done to the Amorites. Numbers 22:2-8 [3] So Moab was in great fear because of the people, for they were numerous; and Moab was in dread of the sons of Israel. Numbers 22:2-8 [4] Moab said to the elders of Midian, “Now this horde will lick up all that is around us, as the ox licks up the grass of the field.” And Balak the son of Zippor was king of Moab at that time. Numbers 22:2-8 [5] So he sent messengers to Balaam the son of Beor, at Pethor, which is near the River, in the land of the sons of his people, to call him, saying, “Behold, a people came out of Egypt; behold, they cover the surface of the land, and they are living opposite me. Numbers 22:2-8 [6] “Now, therefore, please come, curse this people for me since they are too mighty for me; perhaps I may be able to defeat them and drive them out of the land. For I know that he whom you bless is blessed, and he whom you curse is cursed.” “Warnings from the Book of Balaam the son of Beor. He was a seer of the gods.” -Text found at Deir Alla, Jordan in 1967 Image from: from: Image www.bibleodyssey.org - Numbers 22:2-8 [7] So the elders of Moab and the elders of Midian departed with the fees for divination in their hand; and they came to Balaam and repeated Balak's words to him.