Chapter I Foreward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Public/Social Service/Government

Public/Social Service/Government/Education Elias “Bo” Ackal Jr., member of Louisiana House of Representatives 1972-1996, attended UL Lafayette Ernie Alexander ’64, Louisiana representative 2000-2008 Scott Angelle ’83, secretary of Louisiana Department of Natural Resources Ray Authement ’50, UL Lafayette’s fifth president 1974-2008 Charlotte Beers ’58, former under secretary of U.S. Department of State and former head of two of the largest advertising agencies in the world J. Rayburn Bertrand ’41, mayor of Lafayette 1960-1972 Kathleen Babineaux Blanco ’64, Louisiana’s first female governor 2004-2008; former lieutenant governor, Public Service Commission member, and member of the Louisiana House of Representatives Roy Bourgeois ’62, priest who founded SOA Watch, an independent organization that seeks to close the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Corporation, a controversial United States military training facility at Fort Benning, Ga. Charles Boustany Jr. ’78, cardiovascular surgeon elected in 2004 to serve as U.S. representative for the Seventh Congressional District Kenny Bowen Sr. ’48, mayor of Lafayette 1972-1980 and 1992-1996 Jack Breaux mayor of Zachary, La., 1966-1980; attended Southwestern Louisiana Institute John Breaux ’66, U.S. senator 1987-2005; U.S. representative 1972-1987, Seventh Congressional District Jefferson Caffery 1903, a member of Southwestern Louisiana Industrial Institute’s first graduating class; served as a U.S. ambassador to El Salvador, Colombia, Cuba, Brazil, France and Egypt 1926-1955 Patrick T. Caffery ’55, U.S. representative for the Third Congressional District 1968- 1971; member of Louisiana House of Representatives 1964-1968 Page Cortez ’86, elected in 2008 to serve in the Louisiana House of Representatives 1 Cindy Courville ’75, professor at the National Defense Intelligence College in Washington, D.C.; first U.S. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 66,1946

^ , IN^ //': BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON SIXTY-SIXTH SEASON 1946-1947 Constitution Hall, Washington ) ;; VICTOR RED SEAL RECORDS Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Music Director Bach, C. P. E Concerto for Orchestra in D major Bach, J. S Brandenburg Concertos Nos. 3 and 4 Beethoven Symphonies Nos. 2 and 8 ; Missa Solemnis Berlioz Symphony, "Harold in Italy" (Primrose) Three Pieces, "Damnation of Faust", Overture, "The Roman Carnival" '. Brahms . Symphonies Nos. 3, 4 Violin Concerto (Heifetz) Copland "El Sal6n Mexico," "Appalachian Spring" Debussy "La Mer," Sarabande Faur6 "Pelleas et Melisande," Suite Foote Suite for Strings Grieg "The Last Spring" Handel Larghetto (Concerto No. 12), Air from "Semele" (Dorothy Maynor) Harris Symphony No. 3 Haydn Symphonies Nos. 94 ("Surprise") ; 102 (B-flat) Liadov "The Enchanted Lake" Liszt Mephisto Waltz Mendelssohn . Symphony No. 4 ("Italian") Moussorgsky '. "Pictures at an Exhibition" Prelude to "Khovanstchina" Mozart Symphonies in A major (201) ; C major (338), Air of Pamina, from "The Magic Flute" (Dorothy Maynor) Prokofleff .Classical Symphony ; Violin Concerto No. 2 (Heifetz) "Lieutenant Kij6," Suite ; "Love for Three Oranges," Scherzo and March ; "Peter and the Wolf" Rachmaninoff » «- Isle of the Dead" ; "Vocalise" Ravel "Daphnls and Chloe\" Suite No. 2 (new recording Rimsky-KorsakoT "The Battle of Kerjenetz" ; Dubinushka Schubert "Unfinished" Symphony (new recording) ; "Rosa- munde," Ballet Music Schumann Symphony No. 1 ("Spring") Sibelius Symphonies Nos. 2 and 5 ; "Pohjola's Daughter" "Tapiola" ; "Maiden with Roses" Strauss, J Waltzes : "Voices of Spring," "Vienna Blood" Strauss, R J "Also Sprach Zarathustra" "Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks" Stravinsky Capriccio (Sanroma) ; Song of the Volga Bargemen (arrangement) Tchaikovsky Symphonies Nos. -

Spring/Summer 2019

SPRING/SUMMER 2019 CLASSIC ROLL UP GOSSAMER INTRODUCING THE... B166 B176 4” UPTURN BRIM & ROUND CROWN 3 1/2” MEDIUM BRIM & ROUND CROWN GOSSAMER MINI Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection B1899H 50% Paper, 33% Polypropylene, 17% Polyester 50% Paper, 33% Polypropylene, 17% Polyester 3 1/4” MEDIUM BRIM & ROUND CROWN Auburn Sand, Black, Denim Multi, White: 45% Paper, 35% Polypropylene, 20% Polyester Auburn Sand, Black, Denim Multi, White: SPRING/SUMMER 2019 Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection 45% Paper, 35% Polypropylene, 20% Polyester 50% Paper, 33% Polypropylene, 17% Polyester Auburn Sand, Black, Confetti, Denim Multi, White: 45% Paper, 35% Polypropylene, 20% Polyester OCEAN AUBURN SAND DENIM MULTI BLACK MULTI AUBURN SAND CONFETTI DENIM MULTI AUBURN SAND BLACK BLACK MULTI BLACK BLACK MULTI TROPICAL MULTI ECRU WHITE NATURAL CONFETTI ECRU NATURAL ECRU NATURAL NAVY RATTLESNAKE WHITE DENIM MULTI BLACK RATTLESNAKE RATTLESNAKE TRUE RED WHITE CLASSIC ROLL UP GOSSAMER INTRODUCING THE... B166 B176 4” UPTURN BRIM & ROUND CROWN 3 1/2” MEDIUM BRIM & ROUND CROWN GOSSAMER MINI Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection B1899H 50% Paper, 33% Polypropylene, 17% Polyester 50% Paper, 33% Polypropylene, 17% Polyester 3 1/4” MEDIUM BRIM & ROUND CROWN Auburn Sand, Black, Denim Multi, White: 45% Paper, 35% Polypropylene, 20% Polyester Auburn Sand, Black, Denim Multi, White: Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection 45% Paper, 35% Polypropylene, 20% -

The Foreign Service Journal, February 1958

FEBRUARY 1958 The AMERICAN FOREIQN SERVICE PROTECTIVE ASSOCIATION Copies of the Protective Association booklet “Croup Insurance Program—June, 1957” are available at: Protective Association office, 1908 C Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. Foreign Service Lounge, 513, 801 - 19.h Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. Foreign Service Institute, Jefferson-Tyler Bldg., 1018 Wilson Blvd., Arlington, Va. Administrative Offices at foreign posts. This group insurance program may meet your needs. It is worth your study. The Protec¬ tive Association plan is one of the most liberal of such plans in the United States. Members are receiving benefits in various claims at a present rate of more than two hundred thousand dollars annually. The plan: Provides a valuable estate for your dependents in the event of your death. Protects you and your eligible dependents against medical and surgical expenses that might be a serious drain on your finances. Includes accidental death and dismemberment insurance. Entitles members and their eligible dependents to over-age-65 insurance, under the pertinent rules and regulations of the Protective Association. Personnel eligible to participate in the plan are: Foreign Service Officers, Department of State. Foreign Service Staff, Department of State. Foreign Service Reserve Officers, Department of State, when on active service. Permanent American employees of the Foreign Service of the Department of State. ICA (Department of State) Officers, when on active service abroad. ♦ Address applications and inquiries to: THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE PROTECTIVE ASSOCIATION c/o Department of State, Washington 25, D.C., or 1908 G Street, N.W., Washington 6, D.C. Whew—Fait Accompli! WE'VE MOVED TO OUR NEW BUILDING (WITH PARKING LOT) 600 S. -

Philip Roth's Confessional Narrators: the Growth of Consciousness

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1979 Philip Roth's Confessional Narrators: The Growth of Consciousness. Alexander George Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation George, Alexander, "Philip Roth's Confessional Narrators: The Growth of Consciousness." (1979). Dissertations. 1823. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1823 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Alexander George PHILIP ROTH'S CONFESSIONAL NARRATORS: THE GROWTH OF' CONSCIOUSNESS by Alexander George A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 1979 ACKNOWLEDGE~£NTS It is a singular pleasure to acknowledge the many debts of gratitude incurred in the writing of this dissertation. My warmest thanks go to my Director, Dr. Thomas Gorman, not only for his wise counsel and practical guidance, but espec~ally for his steadfast encouragement. I am also deeply indebted to Dr. Paul Messbarger for his careful reading and helpful criticism of each chapter as it was written. Thanks also must go to Father Gene Phillips, S.J., for the benefit of his time and consideration. I am also deeply grateful for the all-important moral support given me by my family and friends, especially Dr. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS June 15, 1983 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS FLAG DAY Colleagues Remarks Made by Dr

15978 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS June 15, 1983 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS FLAG DAY colleagues remarks made by Dr. since it has 92 articles, 16 of which are get Jacques E. Soustelle before the annual ting obsolete; but it is not obscure and HON.RAYMONDJ.McGRATH meeting of the Association of Former see1ns to fulfill the desires to both Right Members of Congress on May 24, 1983. and Left. Our democratic system compares OF NEW YORK both with the Westminster system of the IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES A member of the organization of British and with the American presidential former French deputies <Group des Constitution; it is more presidential than Wednesday, June 15, 1983 Anciens Deputes), Dr. Soustelle is a the British and more parliamentary than • Mr. McGRATH. Mr. Speaker, yes prominent scholar who was one of the yours. terday all Americans celebrated Flag major architects of the constitution of However that may be, the French Repub Day, a day set aside by this Congress the Fifth Republic and a Governor lic today is a democracy, which means that as a national commemoration of the General of Algeria. During the Second my country is a member of an honorable mi symbol of our country. It is unfortu World War, he was decorated by Su nority in the world, but of a minority never preme Allied Commander Gen. theless, while totalitarian, one-party, dicta nate that this day is often overlooked torial, militarist regimes are supreme in by the Nation, for while its celebration Dwight D. Eisenhower for his impor many countries, as well as in the UN, the is not marked by a 3-day weekend or tant role in the liberation of France. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential Election Matthew Ad Vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 "Are you better off "; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election Matthew aD vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caillet, Matthew David, ""Are you better off"; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 2956. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―ARE YOU BETTER OFF‖; RONALD REAGAN, LOUISIANA, AND THE 1980 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Matthew David Caillet B.A. and B.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for the completion of this thesis. Particularly, I cannot express how thankful I am for the guidance and assistance I received from my major professor, Dr. David Culbert, in researching, drafting, and editing my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Wayne Parent and Dr. Alecia Long for having agreed to serve on my thesis committee and for their suggestions and input, as well. -

National Song Binder

SONG LIST BINDER ——————————————- REVISED MARCH 2014 SONG LIST BINDER TABLE OF CONTENTS Complete Music GS3 Spotlight Song Suggestions Show Enhancer Listing Icebreakers Problem Solving Troubleshooting Signature Show Example Song List by Title Song List by Artist For booking information and franchise locations, visit us online at www.cmusic.com Song List Updated March 2014 © 2014 Complete Music® All Rights Reserved Good Standard Song Suggestions The following is a list of Complete’s Good Standard Songs Suggestions. They are listed from the 2000’s back to the 1950’s, including polkas, waltzes and other styles. See the footer for reference to music speed and type. 2000 POP NINETIES ROCK NINETIES HIP-HOP / RAP FP Lady Marmalade FR Thunderstruck FX Baby Got Back FP Bootylicious FR More Human Than Human FX C'mon Ride It FP Oops! I Did It Again FR Paradise City FX Whoomp There It Is FP Who Let The Dogs Out FR Give It Away Now FX Rump Shaker FP Ride Wit Me FR New Age Girl FX Gettin' Jiggy Wit It MP Miss Independent FR Down FX Ice Ice Baby SP I Knew I Loved You FR Been Caught Stealin' FS Gonna Make You Sweat SP I Could Not Ask For More SR Bed Of Roses FX Fantastic Voyage SP Back At One SR I Don't Want To Miss A Thing FX Tootsie Roll SR November Rain FX U Can't Touch This SP Closing Time MX California Love 2000 ROCK SR Tears In Heaven MX Shoop FR Pretty Fly (For A White Guy) MX Let Me Clear My Throat FR All The Small Things MX Gangsta Paradise FR I'm A Believer NINETIES POP MX Rappers Delight MR Kryptonite FP Grease Mega Mix MX Whatta Man -

Steve Smith Steve Smith

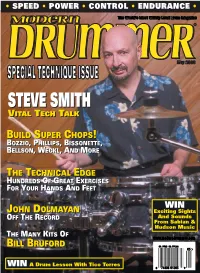

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades. -

The Foreign Service Journal, December 1928

AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL Photo from E. G. Greenie TEMPLE OF HEAVEN, PEKING Vol. V "DECEMBER, 1928 No. 12 The Second, the Third —and the Tenth When an owner of a Graham Brothers Truck or Bus needs another—for replacement or to take care of business expansion—he buys another Graham .... No testimony could be more convincing. Repeat orders, constantly increasing sales, the growth of fleets—all are proof conclusive of economy, de¬ pendability, value. Six cylinder power and speed, the safety of 4-wheel brakes, the known money-making ability of Graham Brothers Trucks cause operators to buy and buy again. GRAHAM BROTHERS Detroit, U.S.A. A DIVISION QF D D n G & BRDTHE-RS C a R P . GRAHAM BROTHERS TRUCKS AND BUSES BUILT BY TRUCK DIVISION OF DODGE BROTHERS SOLD BY DODGE BROTHERS DEALERS EVERYWHERE FOREIGN JOURNAL PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION VOL. V, No. 12 WASHINGTON, D. C. DECEMBER, 1928 The Election THE final count of electoral votes cast in One of the striking features of the election was the election of November 6 shows a total the heavy popular vote for Governor Smith in of 444 votes for Herbert Hoover to 87 for spite of the overwhelming majority of electoral Gov. Alfred E. Smith, of New York, a margin votes for Hoover. The total popular vote was of 178 electoral votes over the 266 necessary for the largest ever polled in any country. The votes a majority. cast in presidential election from 1904 on, taking The popular vote has been variously estimated into account only the major parties, are as to be in the neighborhood of 20,000,000 for follows: Hoover to 14,500,000 for Smith.