Multi-Scale Measurements of Neolithic Ceramics—A Methodological Comparison of Portable Energy-Dispersive XRF, Wavelength-Dispersive XRF, and Microcomputer Tomography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Research Program on Innovations in Prehistory and Antiquity?

Special Volume 6 (2016): Space and Knowledge. Topoi Research Group Articles, ed. by Gerd Graßhoff and Michael Meyer, pp. 777–818. Svend Hansen – Jürgen Renn – Florian Klimscha – Jochen Büttner – Barbara Helwing – Sebastian Kruse The Digital Atlas of Innovations: A Research Program on Innovations in Prehistory and Antiquity Edited by Gerd Graßhoff and Michael Meyer, Excellence Cluster Topoi, Berlin eTopoi ISSN 2192-2608 http://journal.topoi.org Except where otherwise noted, content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 Svend Hansen – Jürgen Renn – Florian Klimscha – Jochen Büttner – Barbara Helwing – Sebastian Kruse The Digital Atlas of Innovations: A Research Program on Innovations in Prehistory and Antiquity The authors discuss the simultaneous appearance of technological innovations in three key technologies (metallurgy, wheeled vehicles, weighing systems) in the second half of the 4th millennium. This is done from a source-critical perspective because the innova- tions are discussed with the help of dynamic maps from the Topoi project Digital Atlas of Innovations. Besides indications of diffusion gradients influenced by special research conditions, exceptional waves of innovation can be detected for all three technologies in the discussed period. These waves of innovation cannot, however, be generalized but have to be understood on the basis of the respective technology traditions and lines of devel- opment specific to local areas. Monocentric diffusion theories can be clearly disproven, local technology developments and their converging in certain centrally situated regions have to be assumed instead. Similarly, the transfer of objects and their châine opératoire can only be detected rather infrequently, while the adaptation to local socio-economic and environmental factors can be demonstrated. -

Ausgabe Oktober 2018

Wird diese Nachricht nicht richtig dargestellt, klicken Sie bitte hier. Liebe Akteurinnen und Akteure der LEADER Region Hümmling, mit diesem Newsletter möchte ich Sie über den aktuellen Stand zum EU-Förderprogramm LEADER informieren. Austausch- und Vernetzungstreffen Das nächste Treffen findet am 13.11.2018 von 18.30 - 20.30 Uhr in der Blockhütte am Freizeitsee Bockhorst, Schulstraße in 26897 Bockhorst statt. Parkplätze stehen vor Ort zur Verfügung. Anmeldungen dazu nimmt das Regionalmanagement Hümmling per E-Mail entgegen. Eine Anfahrtsbeschreibung wird auf Nachfrage zugeschickt. Dieses Treffen dient der weiteren Vernetzung innerhalb der Region Hümmling. Es richtet sich ebenfalls an die Arbeitskreismitglieder des gemeinsamen Arbeitskreises "LEADER". Folgende Tagesordnung ist geplant: 1. Begrüßung 2. Umsetzungsstand LEADER-Region Hümmling 3. Aktivitäten LAG Hümmling 2018 4. Projekte (Dritter) außerhalb der LEADER-Förderung 5. Entwicklung von Projektideen 6. Verschiedenes LAG-Sitzung Am 26.11.2018 um 19.00 Uhr findet die nächste öffentliche Sitzung der Lokalen Aktionsgruppe (LAG) Hümmling in der Samtgemeinde Lathen, Rathaus statt. Projekte In den vergangenen Sitzungen der EU-Förderperiode 2014 - 2020 konnten nun schon über 30 Projekte zur Förderung aus Mitteln der LEADER-Region Hümmling auf Grundlage der drei Handlungsfelder LEBEN, WIRTSCHAFT und NATUR beschlossen werden. Einige davon wurden bereits erfolgreich fertiggestellt. Nähere Informationen erhalten Sie unter www.leader-huemmling.de. Laufende Projekte - Kooperationsprojekt: Mehrgenerationenspielplätze: -

Newsletter Region Hümmling

NEWSLETTER REGION HÜMMLING Ausgabe Nr. 8 07/2011 Liebe Akteurinnen und Akteure der Leader Hümmlinger Pilgerweg Region Hümmling, Auch im laufenden Jahr erfreut sich der mit diesem Newsletter möchte ich Sie über Hümmlinger Pilgerweg großer Beliebtheit. In den aktuellen Stand zum Förderprogramm Zusammenarbeit mit den Tourist-Infos des Leader der Region Hümmling informieren. Hümmlings entwickeln die Pilgerbegleiter ge- führte Touren, die sehr gut nachgefragt werden. Rückblick Die Lokale Aktionsgruppe (LAG) Hümmling hat Fördermittel in Höhe von derzeit 1,731 Mio. gebunden. Während der 18. Sitzung der LAG Hümmling in Werlte wurden drei weitere Be- schlüsse gefasst, so dass nun bereits 56 Pro- jekte positiv bewertet wurden. - Esterwegen: Erweiterung Dorfplatz - Werlte: Hümmlinger Kreisbahn, Bremsanlage - Stavern: Mühle Bruneforth, Sanitärgebäude Beschlossen wurden bislang auch 6 Koopera- tionsprojekte mit anderen LAG Regionen. Da- von wurden 3 Vorhaben bereits umgesetzt. Eine kurze Datenzusammenfassung finden Sie auf der letzten Seite dieses Newsletters. Für die nächste Sitzung der LAG im Oktober 2011 in Sögel wurden schon Projekte angemeldet. Es stehen noch rd. 380 T€ an Fördermitteln aus dem Leaderbudget zur Verfügung. Neue Zeitung, 27.05.2011 Hümmlinger Ferienpassaktion 2011 Die Ferienpassaktion 2011 knüpft nahtlos an die Ems-Zeitung, 12.06.2011 letzte Saison an. Das Titelbild 2011 wurde im Leader Regionen Emsland/Grafschaft Benth. Rahmen des Fotowettbewerbes des vergan- genen Jahres gekürt. In diesem Jahr wird Auf der letzen gemeinsamen Sitzung dieser 6 wieder ein Fotowettbewerb ausgelobt. Das Fe- Regionen in Spelle wurde festgehalten, dass rienpassteam kürt dann die besten Fotos. Auf allein diese Regionen aktuell über 200 Projekte die drei Erstplatzierten warten tolle Preise. Der initiiert haben und dabei 8 Mio. -

Einladung Kreißsaalführung

Ihre Anreisemöglichkeiten Nachfolgend haben wir Ihnen Papenburg Friesoythe Heede B 401 Esterwegen Ihre Anreisemöglichkeit per PKW Hilkenbrook Bösel Breddenberg NL Garrel beschrieben. Dörpen Neubörger Lorup B 72 A 29 Börger B 70 Vrees B 213 Von Süden bzw. Osten kommend Werpeloh Werlte Fahren Sie auf die L53 und biegen rechts in die „Berßener Lathen SÖGEL Molbergen Dienstleistungszentrum Lindern Cloppenburg Straße“–„Amtsstraße“. Am Ende der Straße fahren Sie Stavern Lahn für Gesundheit und Pflege Haren Hüven A 1 Groß Lastrup links Richtung Lathen in die „Wahner Straße“. Nach ca. A 31 (Ems) Berßen B 68 50 m fahren Sie rechts auf den Parkplatz des Hümmling Löningen Bakum Einladung B 213 Vechta Krankenhauses. B 402 Herzlake zur Meppen Dinklage Quakenbrück Von Norden bzw. Westen kommend Kreißsaalführung Fahren Sie auf die L53 (Nordring). Verlassen Sie den Nord- ring im Kreisverkehr und biegen in die „Wahner Straße“ L 53 Werpeloh/Börger (3. Ausfahrt). Nach ca. 200 m fahren Sie links auf den Lathen/B 70 Parkplatz des Hümmling Krankenhauses. MühlenstraßeSigiltrastraße Nordring Wahner Straße Spahnharrenstätte Zum Parken nutzen Sie bitte die ausgewiesenen, P Spahner Straße SÖGEL Fried-hof kostenlosen Parkplätze. Westring P Garten- Am Krankenhaus T str. orf sweg Cl fehn emen L 53 s - A ugus t-St Sprakeler Straße r Amtsstr. W e Berßener Straße rl te Werlte Püttkesberge r S tra ße Meppen L 53 Dienstleistungszentrum Klinik für Geburtshilfefür Gesundheit und Pflege Mühlenstraße 17 49751 Sögel Telefon 05952/209-179 Telefax 05952/209-299 Individuelle Geburtshilfe mit hohem Email: [email protected] Sicherheitsstandard. Internet: http://www.krankenhaussoegel.de Hümmling Krankenhaus Sögel: „da will ich hin“… Einladung Unsere Leistungen auf einen Blick Liebe werdende Mutter, Wir bieten Ihnen … Und nach dem Krankenhaus …? lieber werdender Vater, • Qualifiziertes Fachpersonal Mit der Entbindung und der Erstversorgung endet die Be- treuung durch das Hümmling Krankenhaus aber nicht. -

1/98 Germany (Country Code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The

Germany (country code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA), the Federal Network Agency for Electricity, Gas, Telecommunications, Post and Railway, Mainz, announces the National Numbering Plan for Germany: Presentation of E.164 National Numbering Plan for country code +49 (Germany): a) General Survey: Minimum number length (excluding country code): 3 digits Maximum number length (excluding country code): 13 digits (Exceptions: IVPN (NDC 181): 14 digits Paging Services (NDC 168, 169): 14 digits) b) Detailed National Numbering Plan: (1) (2) (3) (4) NDC – National N(S)N Number Length Destination Code or leading digits of Maximum Minimum Usage of E.164 number Additional Information N(S)N – National Length Length Significant Number 115 3 3 Public Service Number for German administration 1160 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 1161 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 137 10 10 Mass-traffic services 15020 11 11 Mobile services (M2M only) Interactive digital media GmbH 15050 11 11 Mobile services NAKA AG 15080 11 11 Mobile services Easy World Call GmbH 1511 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1512 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1514 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1515 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1516 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1517 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1520 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH 1521 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH / MVNO Lycamobile Germany 1522 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone -

Abhandlungen Herausgegeben Vom Naturwissenschaftlichen Verein Zu

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Abhandlungen des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins zu Bremen Jahr/Year: 1890-1891 Band/Volume: 12 Autor(en)/Author(s): Sandstede Heinrich (Johann) Artikel/Article: Beiträge zu einer Lichenenflora des nordwestdeutschen Tieflandes 209-236 © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at Beiträge zu einer Liclieiieiiflora des nordwest- deutsciien Tieflandes. (Erster Naclitrag.) Von Heinr. Sandstede. Fortgesetzte Ausflüge innerhalb des oben bezeichneten Gebietes ermöglichten den folgenden Nachtrag, der sich auf Species und Formen erstreckt, welche für das Gebiet neu sind, oder neu erschlossene Standorte bereits beobachteter Lichenen betrifft. Auch minder seltene Arten haben Aufnahme gefunden, sofern die Unterlage, auf der die Pflanze wächst, eine von der Regel abweichende ist. Wenn allgemein verbreitete Flechten, wie z. B. Usnea florida und Physcia tenella auf Eisenschlacken, oder wenn Lecidea parasema und L. myriocarpa auf dürren Phragmiteshalmen der Reitdächer vorkommen, so glaube ich dies anführen zu dürfen. Andere Flechten, welche zwar in Band X dieser Abhaüdlungen p. 439 —480 aufgeführt sind, aber unter nach- stehenden Zusätzen fehlen, weil nennenswerte Standorte nicht gefunden wurden, sind durch Einschaltung ihrer Ordnungsnummer gekennzeichnet. Dies Verfahren bezweckt die Aufrechterhaltung der systematischen Reihenfolge. Die Wiedergabe mehrfacher Aufzeichnungen aus dem früheren Fürstentum Lüneburg habe ich einstweilen vermieden. Ich hoffe, dass in den nächsten Jahren ein Nachtrag erscheinen kann, der diesen Teil des niedersächsischen Tieflandes separat behandelt. Dagegen wird man vorzugsweise viele Angaben vom Hümmling, einer hügeligen Landschaft zwischen Meppen und Papenburg, sowie mehreres aus dem Küstenstriche von Cuxhafen bis Emden vorfinden. Für die Ex.<iccaten werke konnte inzwischen rege gesammelt werden. -

Altglascontainer-Standorte Altkreis ASD Stand Dez. 20

Stadt Papenburg 26871 Papenburg Flachsmeerstraße Wertstoffhof 26871 Papenburg Rheiderlandstraße Wertstoffhof 26871 Papenburg Herzogstr. 101 Gaststätte Schmitz Herbrum 26871 Papenburg Ecke Bokeler Str. / Moorkämpe 26871 Papenburg Tunxdorfer Str. Containerplatz 26871 Papenburg Hauptkanal re. 64 Paprkplatz Ceka 26871 Papenburg Bürgermeister-Hettlage-Str.19 26871 Papenburg Moorstr. 24 Edeka 26871 Papenburg Am Rathaus Rathaus, Schützenplatz 26871 Papenburg Hans-Böckler-Str 16 26871 Papenburg Baltrumer Str. 34 26871 Papenburg Margarethe-Meinders-Straße 34 Kapitän Siedlung 26871 Papenburg Königsberger Str. 34 Vosseberg 26871 Papenburg Hedwigstr 27 26871 Papenburg Kleiststr. 12 Schule Busshaltestelle 26871 Papenburg Querweg 13 26871 Papenburg Schäfereiweg 42 Kreutzmann 26871 Papenburg Am Stadion Wald Stadion 26871 Papenburg Barenbergstr. 75 Tennishalle 26871 Papenburg Hans-Nolte-Str 26871 Papenburg Umländerwiek 5 Combi 26871 Papenburg Lüchtenburg re. 90 Ecke Schulte Lind Reithalle 26871 Papenburg Erste Wiek 145 rechts beim Sportplatz 26871 Papenburg Forststr. 21 26871 Papenburg Lüchtenburg li. 85 Gaststätte Rolfes 26871 Papenburg Birkenallee 135 Bethlehem links 26871 Papenburg Splitting li. 195 Eintracht Stadion 26871 Papenburg Splitting li. 262 26871 Aschendorf An den Bleicherkolken 1 Combi Markt 26871 Aschendorf In der Emsmarsch Wertstoffhof 26871 Aschendorf Bülte II 26871 Aschendorf Glatzer Strasse 5 ASD Moor Sportplatz 26871 Aschendorf Münsterstr. 35 26871 Aschendorf Am Brink 7a Getränkemarkt 26871 Aschendorf Am Vossschloot 1 Nähe Klinik -

Members and Sponsors

LOWER SAXONY NETWORK OF RENEWABLE RESOURCES MEMBERS AND SPONSORS The 3N registered association is a centre of expertise which has the objective of strengthening the various interest groups and stakeholders in Lower Saxony involved in the material and energetic uses of renewable resources and the bioeconomy, and supporting the transfer of knowledge and the move towards a sustainable economy. A number of innovative companies, communities and institutions are members and supporters of the 3N association and are involved in activities such as the production of raw materials, trading, processing, plant technology and the manufacturing of end products, as well as in the provision of advice, training and qualification courses. The members represent the diversity of the sustainable value creation chains in the non-food sector in Lower Saxony. 3 FOUNDING MEMBER The Lower Saxony Ministry for Food, Agriculture and Con- Contact details: sumer Protection exists since the founding of the state of Niedersächsches Ministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Verbraucherschutz Lower Saxony in 1946. Calenberger Str. 2 | 30169 Hannover The competences of the ministry are organized in four de- Contact: partments with the following emphases: Ref. 105.1 Nachwachsende Rohstoffe und Bioenergie Dept 1: Agriculture, EU farm policy (CAP), agricultural Dr. Gerd Höher | Theo Lührs environmental policy Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Dept 2: Consumer protection, animal health, animal Further information: www.ml.niedersachsen.de protection Dept 3: Spatial planning, regional development, support Dept 4: Administration, law, forests Activities falling under the general responsibility of the ministry are implemented by specific authorities as ‘direct’ state administration. -

The New Audi A3 Sportback G-Tron

Product and Technology Communications Josef Schloßmacher Tel: +49 841 89-33869 e-mail: [email protected] www.audi-mediaservices.com The new Audi A3 Sportback g-tron The new A3 Sportback g-tron is powered by the CO2-neutral Audi e-gas CO2 emissions of 30 grams per kilometer (48.28 g/mile) Total range of 1300 km (807.78 miles) Ingolstadt, March 1, 2013 – Audi is taking a large step towards sustainable mobility with the A3 Sportback g-tron. The compact five-door car, due to make its debut at the end of the year, is powered by the CO2-neutral fuel Audi e-gas. The fuel will be produced in the power-to-gas plant in Werlte, Germany. This new car innovatively combines ecological balance, economy and high-tech solutions. The Audi A3 Sportback g-tron comes with the full gamut of Audi’s technology expertise – from ultra-lightweight technology, and infotainment, to driver assistance systems. But first and foremost it showcases state-of-the-art CNG drive technology, starting with the fuel storage. Its two tanks under the luggage compartment floor can each hold seven kilograms (15.43 lb) of CNG at a maximum 200 bar pressure. In tune with the ultra-lightweight construction concept, each tank weighs 27 kilograms (59.52 lb) less than its conventional counterpart. The tanks consist of a new type of matrix. The inner layer consists of gas- impermeable polyamide polymer, while a second layer of carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) gives the tank its extremely high strength; a third layer of glass fiber reinforced polymer (GFRP) provides rugged protection against damage from the outside. -

Windblatt 01/2017 Impressive Start for ENERCON's New Flagship Download

windblatt – the ENERCON magazine 01_2017 Visit ENERCON at the HANNOVER MESSE 2017 from 24 to 28 April! Hall 27 I Booth H70 LAUNCH OF E141 EP4 Impressive start for ENERCON’s new flagship START-UP SUPPORT FOR ELECTRIC MOBILITY ___ ENERCON develops quick charging solution PARTNERSHIP IN TENDERING SYSTEM ___ ENERCON offers medium-sized investors its support PROJECT LOGISTICS BY RAIL ___ ENERCON’s e.g.o.o. transports tower segments windblatt 01_2017 1 CONTENT_ _EDITORIAL STANDARDS TABLE OF CONTENT Keeping climate protection 03 _ EDITORIAL TITLE PRACTICE on the agenda 04 _ VIEW 10_ Launch of E-141 EP4 24 _ ENERCON as project partner 06 _ ENERCON NEWS After putting its prototype into operation, ENERCON offers medium-sized investors its 07_ ADDRESSES ENERCON is off to a flying start with the support in the tendering system. 09 _ DATES new E-141 EP4. Dear Readers, Customers, Business Partners and Employees, 26 _ Background to the tendering system TECHNOLOGY Germany is to launch a competition-based funding who would ever have dreamed that global climate protection 16 _ ENERCON quick charging solution scheme for electricity from renewable sources. would once again be called into question like this? It seemed to be Based on its interface for connecting energy storage The first round of tendering is scheduled for May. a matter of general consensus that climate change represented systems to the grid, ENERCON has developed a a serious risk to man and the environment. Even if the international community disagreed quick charging solution for electric vehicles. 27 _ ENERCON’s strengths in the tendering system about the scope and timing of measures, there was general unanimity about the necessity of ENERCON Head of Sales, Stefan Lütkemeyer, climate protection measures. -

Index of Subjects

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83875-7 - Jewish Forced Labor Under the Nazis: Economic Needs and Racial Aims, 1938-1944 Wolf Gruner Index More information Index of Subjects Aktion Erntefest, 271 Autobahn camps, 286 Aktion Hase, 96 acceptance/rejection of Jews for, 197, Aktion Mitte B, 97 198 Aktion Reinhard, 258 administration of by private companies, Aktion T4, 226 203 Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse (AOK). See closing of, 208, 209, 211 General Local Health Insurance control of by Autobahn authorities, 199, Provider. 203, 213, 219 Annexation of Austria. See Anschluss. control of by SS (Schmelt), 214, 223 Anschluss (annexation of Austria), xvi, xxii, employing Polish Jews, 183, 198, 203, 3, 105, 107, 136, 278 217, 286 Anti-Jewish policy locations of, 203, 212, 219, 220 before 1938, xx, xxii, xxiv redesignation of as “Zwangsarbeitslager,” central measures in, xxi, xxii, xxiii 223 consequences of for Jews, xvi, 107, 109, regulations for, 199, 200, 203, 212 131, 274 See also Fuhrer’s¨ road and Schmelt forced contradiction in, 109 labor camps. diminished SS role in, 240, 276 Autobahn construction management division of labor principle in, xvii, xviii, headquarters (Oberste Bauleitung der xxiv, 30, 112, 132, 244, 281, 294 Reichsautobahnen) effect of war on, 8, 9, 126, 141, 142 in Austria, 127 forced labor as element of, x, xii, xiii, 3, 4, in Berlin, 199, 200, 202, 203, 204, 205, 177, 276 206 in Austria, 136 in Breslau, 204, 205, 211, 212, 220, local-central interaction in, xx, xxi, xxii 222 local measures in, xxi, xxii, xxiii, 150, in Cologne, 205 151 in Danzig, 203, 204, 205 measures implementing, 151, 172, 173, See also Reich Autobahn Directorates. -

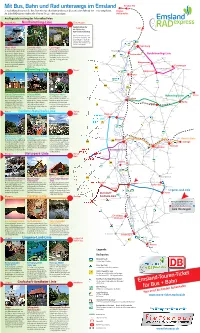

Mit Bus, Bahn Und Rad Unterwegs Im Emsland Emden Hbf Je Nach Wunsch Starten Sie Ihre Tour Mit Bus Oder Bahn Und Setzen Diese Mit Dem Fahrrad Fort - Oder Umgekehrt

Mit Bus, Bahn und Rad unterwegs im Emsland Emden Hbf Je nach Wunsch starten Sie Ihre Tour mit Bus oder Bahn und setzen diese mit dem Fahrrad fort - oder umgekehrt. Emden An jeder RADexpress-Haltestelle können Sie zu- oder aussteigen. Außenhafen Ausfl ugsziele entlang der Fahrradbuslinien: Papenburg Nordhümmling-Linie Esterwegen Express Gedenkstätte für Leer die Opfer des Nationalsozialismus Zwischen Mai und September können Besucher jeden 1. und 3. Sonntag um 11 Uhr die im Bau befi ndliche Gedenkstätte Meyer Werft Ems Route besuchen. Die Eröffnung ist für Oktober 2011 geplant. Route 5,5 10,1 Papenburg Meyer Werft Surwolds Wald Esterwegen In den riesigen Baudocks werden Der im Erholungsgebiet liegende Moor ist das prägende Element 5,7 6,3 Kreuzfahrtschiffe gebaut, die die Kletterwald in den Kronen der des staatlich anerkannten Erho- Rhede Route Besucher zum Staunen bringen. hohen Bäume ist eine Attraktion. lungsortes. Darüber informiert Aschendorf Nordhümmling-Linie Führungen im dortigen Besucher- Märchenwald, Riesenrutsche Frosch Esti auf dem Moorer- Route 12,4 zentrum oder im „Zeitspeicher“ und Waldmuseum locken die lebnispfad. Von hier ist es nicht 13,0 Bockhorst auf dem Gelände der Alten Werft 9,0 kleineren Besucher in den staat- weit zum Erholungsgebiet am 7,0 1,7 informieren über die Schiffsbau- Vlagtwedde lich anerkannten Erholungsort Erikasee. 6,0 7,8 Küstenkanal tradition. Die Von-Velen-Muse- Börgermoor 4,1 Surwold. Yachthafen, Freizeitsee 6,8 umsanlage zeigt die Entwicklung und das Café Idylle runden das Bourtange 13,4 Leher Pünte