View of the Related Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DMINENT RESUME Lists the Citations in Alphabetical Order.Bytitle

DMINENT RESUME ED 203 381' CS 206 475 AUTHOR May, Jill P. TITL$ Films and Filmstrips for Language Arts: An Annotated 'Bibliography. INSTITUTION National Council ,,of Teachers of .English, .Urbana, REPORT. NO Ill.- ISBN -0- 8141 - 1726 -0 PUB DATE . 81 NOTE 100p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council-of Teachers o nglish, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801(Stock No. 17260, $5.00 member, $5.75 non-member)." . EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies: Audibvisual Aids: :1*Childrens Literature: Elementary Education; *Filmstrips: *Instructional Films; *Instructional Materials: *Language Arts -,,, ABSTRACT Intended for use with children ages three through twelve, this bibliography cites films.and,filmstrips covering ,children's literature and a variety of.other instructional subjects.. Following an introductiOn that discusses the selection, criteriaused for the bibliography and how to use the book, the annotationportion' lists the citations in alphabetical order.bytitle. Citationsinclude format, running time, ang most appropriate grade leVel. A list of distributors and produces fallows,the annotations. 'Author and .title , indexes to children's Werature:and a subject indet to,the films.and filmstrips conclude the bibliography. IBM 6 I I c **********************44**************p**********Ii********************* ReproOuctions(supplied by EDRS are the test thatcan be made * from the original document. , ******************************************************************** CC) lb r(N Films and Filmstrips cp for Language Arts .. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION (N.,1 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION C:) ... EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) ' 1.4., +Hes documenthas 'been reproductitas , .. r received from, the person or organization originating it. An Annotated.Bibliography HMinor changes have been made to improve . reproduction quality. 4o-ints of view or opinions stated in this docu- ment do not necessarily represent official NIE position.orpolicy. -

Kids, Libraries, and LEGO® Great Programming, Great Collaborations

Children the journal of the Association for Library Service to Children Libraries & Volume 10 Number 3 Winter 2012 ISSN 1542-9806 Kids, Libraries, and LEGO® Great Programming, Great Collaborations Playing with Poetry PERMIT NO. 4 NO. PERMIT Change Service Requested Service Change HANOVER, PA HANOVER, Chicago, Illinois 60611 Illinois Chicago, PAID 50 East Huron Street Huron East 50 U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Association for Library Service to Children to Service Library for Association NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT Table Contents● ofVolume 10, Number 3 Winter 2012 Notes 28 Louisa May Alcott The Author as Presented in 2 Editor’s Note Biographies for Children Sharon Verbeten Hilary S. Crew 36 More than Just Books Features Children’s Literacy in Today’s Digital Information World 3 Arbuthnot Honor Lecture Denise E. Agosto Reading in the Dark 41 Peter Sís From Board to Cloth and Back Again 9 C Is for Cooperation A Preliminary Exploration of Board Books Public and School Library Allison G. Kaplan Reciprocal Responsibility in Community Literacy Initiatives 45 Play to Learn Janet Amann and Sabrina Carnesi Free Tablet Apps and Recommended Toys for Ages 3-7 14 He Said, She Said Hayley Elece McEwing How the Storytime Princess and the Computer Dude Came Together to Create a Real-Life Fairytale Shawn D. Walsh and Melanie A. Lyttle Departments 17 The People on the Bus . 35 Author Guidelines Louisiana Program Targets Community Literacy 40 Call for Referees Jamie Gaines 52 Children and Technology 20 Brick by Brick Here to Stay ® LEGO -Inspired Programs in the Library Mobile Technology and Young Tess Prendergast Children in the Library Amy Graves 24 Carnegie Award Acceptance Speeches 55 School-Age Programs and Services Bringing Lucille to Life Kick Start Your Programming! Melissa Reilly Ellard and Paul R. -

Duncan Public Library Board of Directors Meeting Minutes June 23, 2020 Location: Duncan Public Library

Subject: Library Board Meeting Date: August 25, 2020 Time: 9:30 am Place: Zoom Meeting 1. Call to Order with flag salute and prayer. 2. Read minutes from July 28, 2020, meeting. Approval. 3. Presentation of library statistics for June. 4. Presentation of library claims for June. Approval. 5. Director’s report a. Summer reading program b. Genealogy Library c. StoryWalk d. Annual report to ODL e. Sept. Library Card Month f. DALC grant for Citizenship Corner g. After-school snack program 6. Consider a list of withdrawn items. Library staff recommends the listed books be declared surplus and be donated to the Friends of the Library for resale, and the funds be used to support the library. 7. Consider approving creation of a Student Library Card and addition of policy to policy manual. 8. Old Business 9. New Business 10. Comments a. By the library staff b. By the library board c. By the public 11. Adjourn Duncan Public Library Claims for July 1 through 31, 2020 Submitted to Library Board, August 25, 2020 01-11-521400 Materials & Supplies 20-1879 Demco......................................................................................................................... $94.94 Zigzag shelf, children’s 20-2059 Quill .......................................................................................................................... $589.93 Tissue, roll holder, paper, soap 01-11-522800 Phone/Internet 20-2222 AT&T ........................................................................................................................... $41.38 -

A#1140 -: Chilatenslibrarians Are Increasingly ,Aware- of The

DOCOMEMS RESUME .p)- 077237 M 011 160 47'44 Ends in Children's Programs. A Bibliography Prepared by the Film Committee of the Children's and Young* People's Services Section oftheWisconsin Library Association. INSTITUTION Wisconsin Library Association; Madison. POEDATE 72 -NOTE 39p. AVAlIAELEFROMWisconsin Library, Association, 261 West Mifflin Street,,MadleOn-, j_WiscfOnSin-53703 = EDNS-PBICE MF-$O.65HC Not Available from DESORI-PTONS Bibliographies; : CatalCgSt. *Children;4Ti lm.Libraries;1 4,E-110S; -Guides A#1140 -: ChilatenSlibrarians are increasingly ,aware- of the 'value offilmsin programing::: films -are_ attractive to _children, -they _-_-illnitinate,the familiar ,;and i suggest new areas_ of interest to .explore,- and theyc:an_.ttoii-cw -,backgroundand open new -vistas : for the 41-71i*.a11.4-401411,40t.af40-0-111.-This -t-lti-P5.1-0cliti-On.,of the liStifig, -presentS-selections for-US!:in _- - ---,.. _-prfOgraMS--With-_-Children- frObs- gtadeS- three through _Sit,- with -information _ -,-,- -.- -- - .on- xi-inning,time,_-Prcidlider, :01S4i:biltCr 0'price, Whether itS-- black-and-white or -color,: and the :content. N bibliography of aids : forlibrary:use,a-_list of sources for- the selection of films, and a-cliktor--ofdistributors for purchase andrentalare riialtidEd: ._(SH)- ,=;-:±. FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY 434odfosts, A_= Bibliography prepared.,by the Film Coamittee-=of' and xeisig;kekiii._!ir*!t*icks Sebtion:of the; A060.-ittion- WISCONSIN LIBRARY-ASSOCIATION 1 201 West Mifflinstieet- Nadiloti,Wis.3703 FILMS! IN'tifILDNEN'SiTNOGNANS-, A :Bibliography prepared' bzittie-FilmCommittee =of the Childten_is andYoungpeoPle!s Seitides -Section-ofthe Wisconsin Library AsSociation- 1972 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. -

Book Banquet. a Summer Reading Program Manual. INSTITUTION New York State Library, Albany

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 364 IR 054 929 AUTHOR Ward, Caroline; Levine, Joyce TITLE Book Banquet. A Summer Reading Program Manual. INSTITUTION New York State Library, Albany. SPONS AGENCY Gaylord Bros., Liverpool, NY.; Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. Office of Library Programs. PUB DATE 93 NOTE 283p.; Art by Steven Kellogg and Rachel S. Fox. PUB TYPE Guides NonClassroom Use (055) Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art Activities; Childrens Art; *Childrens Libraries; *Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; Library Planning; *Library Services; Nonfiction; Program Development; Program Implementation; Publicity; *Public Libraries; *Reading Programs; Resource Materials; State Libraries; State Programs; *Summer Programs IDENTIFIERS New York State Library ABSTRACT This manual for the 1993 New York State summer reading program, "Book Banquet," ties books and reading together with the theme of eating. The manual offers program ideas, activities, and materials. The following chapters are included: (1) "Appetizers" (planning, publicity, and promotion);(2) "Setting the Table" (decorations and display);(3) "Main Course--Reading";(4) "a la carte" (programs and activities);(5) "Delectable Desserts" (crafts, games, puzzles, mazes, and shopping); and (6) "Basic Pantry" (books, media, and other resources). The annotated bibliography of the "Basic Pantry" section includes 130 works of fiction for children, 106 works of -

Where Books Come Alive!

PUBLIC PERFORMANCE DVDS,VIDEOS AND AUDIO BASED ON OUTSTANDING CHILDREN’S BOOKS Where Books Come Alive! Table of Contents Where Books Come Alive! Fall 2008 New Releases page 4-5 Spring 2008 New Releases page 6-7 For more than 50 years, Weston Woods’ The Playaway® Audio Collection page 8-9 mission has been to motivate children to want New and Noteworthy page 10 to read. Every book is brought to life through Story Hour Collection page 11-41 engaging visuals and stirring word-for-word Alphabetical Listing narrations. They are accompanied by an SPECIAL COLLECTIONS History page 42-43 original musical score, composed to perfectly Author Documentaries page 44 fit the mood and nuances of each story. Caldecott/Newbery page 45 All of our new DVD titles have added bonus features to Foreign Language page 46-47 further enhance the experience of seeing your favorite Rabbit Ears® page 48 Scholastic Entertainment page 49 books brought to life. These features include: Scholastic Audio page 50-55 ★Read-Along allows children to follow WESTON WOODS’STORY COLLECTIONS ON DVD each word as it is simultaneously Read- Thematic DVD page 68-70 narrated and highlighted on the Along! Story Collections screen, strengthening vocabulary, Spanish Bilingual DVD page 70 comprehension and fluency. All new DVDs now offer Story Collections three viewing options: Read-Along, closed-captioned Favorite Author DVD page 71 Story Collections subtitles or no text at all. ★Closed-captioned subtitles and/or subtitled captions - INDEXES Thematic Index page 56-57 Closed–captioned subtitles include Month-by-Month Index page 58-59 descriptive text for the hearing Critic’s Choice – Best Titles page 60 impaired, while subtitled captions from Other Producers contain only the spoken Alphabetical Index of page 61-67 narration and character Weston Woods’ Titles dialogue (without descriptive text) for use as a reading EXPANDED PURCHASING OPTIONS AVAILABLE! tool. -

![Lucy Kroll Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3113/lucy-kroll-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-2283113.webp)

Lucy Kroll Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Lucy Kroll Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2002 Revised 2010 April Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms006016 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm82078576 Prepared by Donna Ellis with the assistance of Loren Bledsoe, Joseph K. Brooks, Joanna C. Dubus, Melinda K. Friend, Alys Glaze, Harry G. Heiss, Laura J. Kells, Sherralyn McCoy, Brian McGuire, John R. Monagle, Daniel Oleksiw, Kathryn M. Sukites, Lena H. Wiley, and Chanté R. Wilson Collection Summary Title: Lucy Kroll Papers Span Dates: 1908-1998 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1950-1990) ID No.: MSS78576 Creator: Kroll, Lucy Extent: 308,350 items ; 881 containers plus 15 oversize ; 356 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Literary and talent agent. Contracts, correspondence, financial records, notes, photographs, printed matter, and scripts relating to the Lucy Kroll Agency which managed the careers of numerous clients in the literary and entertainment fields. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Braithwaite, E. R. (Edward Ricardo) Davis, Ossie. Dee, Ruby. Donehue, Vincent J., -1966. Fields, Dorothy, 1905-1974. Foote, Horton. Gish, Lillian, 1893-1993. Glass, Joanna M. Graham, Martha. Hagen, Uta, 1919-2004. -

ED 119 399 Publishers and Producers in the U.S. Canada

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 119 399 95 EC 081 389 TITLE Publisher Source Directory: A List of Where to Buy or Rent Instructional Materials and Other Educational ' Aids, Devices, and Media Including More Than 1,600 Publishers and Producers in the U.S. Canada, and Europe. Revised Edition. INSTITUTION National Center on Educational Media and Materials for the Handicapped, Columbus, Ohio. SPONS AGENCY Bureau of Education for the Handicapped (DHEW/OE), Washington, D.C. REPORT NO NC-75 303 PUB DATE Oct 75 CONTRACT OEC-300-72-4478 NOTE 86p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$4.67 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Audiovisual Aids; Books; Electromechanical Aids; Exceptional Child Education; Films; *Handicapped Children; *Instructional Materials; *Instructional Media; *Resource Guides; Tape Recordings; Toys ABSTRACT Listed are more than 1,600 publishers, producers, and distributors of educational materials for use with the handicapped. Entries are presented in alphabetical order according to name. Beneath each source's name and address are code numbers which correspond to the type of materials each publisher's catalog lists. Provided is a list of the codes and definitions for 74 types of instructional aids, devices, and/or media which include books, audiovisual aids, films, tapes, electromechanical aids, and toys. (SB) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. -

CSIF/Calgary Public Library 16Mm and Super 8 Film Collection

CSIF Film Library CSIF/Calgary Public Library 16mm and Super 8 Film Collection Film Running Time Number Title Producer Date Description (min) A long, hard look at marriage and motherhood as expressed in the views of a group of young girls and married women. Their opinions cover a wide range. At regular intervals glossy advertisements extolling romance, weddings, babies, flash across the screen, in strong contrast to the words that are being spoken. The film ends on a sobering thought: the solution to dashed expectations could be as simple as growing up before marriage. Made as part of the Challenge for Change 1 ... And They Lived Happily Ever After Len Chatwin, Kathleen Shannon 1975 program. 13 min Presents an excerpt from the original 1934 motion picture. A story of bedroom confusions and misunderstandings that result when an American dancer begins pursuing and English woman who, in turn, is trying to invent the technical grounds of 2 Gay Divorcee, The (excerpt) Films Incorporated 1974 divorce 14 A hilarious parody of "Star Wars". Uses a combination of Ernie Fosselius and Michael Wiese special effects and everyday household appliances to simulate 4 Hardware Wars (Pyramid Films) 1978 sophisticated space hardware. 10 Laurel and Hardy prepare for a Sunday outing with their wives 5 Perfect Day, A Hal Roach Studios (Blackhawk Films) 1929 and Uncle Edgar Kennedy, who has a gouty foot. 21 Witty, sad, and often bizarre anecdotes of Chuck Clayton, the 73-year-old former manager of the largest cemetery east of 6 Boo Hoo National Film Board of Canada 1975 Montreal, told as he wanders nostalgically through its grounds. -

2009 Environmental Film Festival Guide

17TH ANNUAL MARCH 11–22, 2009 130 documentary, feature, animated, archival, experimental and children’s films Most screenings include discussion and are free Special Pre-Festival Event on March 10 WWW.DCENVIRONMENTALFILMFEST.ORG EMAIL: [email protected] PHONE: 202.342.2564 FAX: 202.298.8518 th President & Founder: Welcome to the 17 Annual Flo Stone STAFF Environmental Film Festival! Executive Director: Peter O’Brien As the first decade of the 21st century closes, the Environmental Film Festival marks its 17th year Managing Director: in Washington, D.C. with an astounding diversity of films that capture the majesty of our world Christopher Head and address the ever-increasing threats to life on earth. The 2009 Festival spotlights earth’s final Public Affairs Director: Helen Strong frontier, the ocean, source of all life, covering nearly three quarters of the globe but less known Associate Director: than the surface of the moon. Please join us this March to explore our water planet through the Georgina Owen Festival’s 130 films, enhanced with the perspectives and knowledge of 50 filmmakers and 72 Program Associates: special guests who will be on hand for the Festival. Maribel Guevara Anne-Clemence Owen Festival Interns: Earth: The Biography – Oceans and The State of the Planet’s Oceans illuminate the defining role Miranda Lievsay played by the ocean and investigate its current health and sustainability. Secrets of the Reef Naimah Muhammad Kaitlin Whitman immerses the viewer in the metropolis of a coral reef, Colour Talks shows how fish use color for Development Associate: camouflage and Cuttlefish: The Brainy Bunch captures the bizarre antics of this amazing sea Christa Carignan creature. -

Timeline Inside Single Pgs.Qxd

1953 - 2003 weston woods® elebrating CC 50 Years of Bringing Books to Life n a little log cabin in the back woods of Weston, Connecticut, IMorton Schindel became fascinated with picture books while reading to his children. He wanted to do more than read these books though; he wanted to bring them to life. At that time, the idea of animating children’s books was unknown. But his interest became a dream that became a company and Weston Woods Studios was born. ince 1953, Weston Woods Studios has produced more than 500 films Sand filmstrips and given many thousands of children a new and exciting view of the picture books they love. For 50 years, we have demonstrated that faithful picture book adaptations succeed in whetting children’s appetites for turning and returning to the books on which they are based, helping children to develop a lifelong love of reading and literature. Thanks to all of you for helping make Weston Woods synonymous with quality, caring, and the best for children! n nnnnnnnnn nnn1n954 nnnnn nnnn nnn nnn nnnn nnn nnn nn nnn nnn Contract for nnn nnn nnn nnn the first production n n nn nn nn nn ANDY AND THE LION n nn nn n nn nn based on the Caldecott nn nn n nn nn nn Honor Book nn nn nn nnn nn nn nnn by James nn nn nnn nn nn nnn nn nn n n n n n n n n nnnn Daugherty nn nn nnnnnnnnnnnnnnn1nn953nnnnnn nn nnn nnn is signed nnn nn nn nnnn nnnn nnn nnn1nn956nnnnnnnnnnnnnn First public screening of Weston Woods films at the Museum of Modern Art in New York NY Morton Schindel founder of Weston Woods sets up shop in the wilderness -

Library Weeding Log Martin Luther King Jr

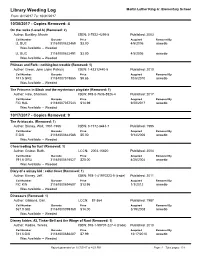

Library Weeding Log Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School From: 8/1/2017 To: 10/31/2017 10/30/2017 - Copies Removed: 4 On the rocks (Level A) (Removed: 2) Author: Buckley, Marvin ISBN: 0-7922-4299-8 Published: 2003 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By LL BUC 31161000622459 $3.00 4/5/2006 aswebb Was Available -- Weeded LL BUC 31161000622491 $3.00 4/5/2006 aswebb Was Available -- Weeded Phineas and Ferb : nothing but trouble (Removed: 1) Author: Green, John (John Patrick) ISBN: 1-42312440-5 Published: 2010 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 741.5 GRE 31161007019865 $9.86 10/6/2010 aswebb Was Available -- Weeded The Princess in Black and the mysterious playdate (Removed: 1) Author: Hale, Shannon. ISBN: 978-0-7636-8826-4 Published: 2017 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By FIC HAL 31161007057543 $14.99 9/20/2017 aswebb Was Available -- Weeded 10/17/2017 - Copies Removed: 9 The Aristocats. (Removed: 1) Author: Disney, Walt, 1901-1966 ISBN: 0-7172-8441-7 Published: 1995 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By E DIS 31161000644586 $5.00 9/14/2006 aswebb Was Available -- Weeded Cheerleading for fun! (Removed: 1) Author: Gruber, Beth. LCCN: 2003-15820 Published: 2004 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 791.6 GRU 31161000616527 $20.00 4/26/2004 aswebb Was Available -- Weeded Diary of a wimpy kid : cabin fever (Removed: 1) Author: Kinney, Jeff. ISBN: 978-1-41970223-5 (trade) Published: 2011 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By FIC KIN 31161000694607 $13.95 1/3/2012 aswebb Was Available -- Weeded Dinosaurs (Removed: 1) Author: Gibbons, Gail.