Human Mucin 7, Secreted (MUC7) ELISA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mucin Family Genes Are Downregulated in Colorectal

ooggeenneessii iinn ss && rrcc aa MM CC uu tt ff aa Journal ofJournal of oo gg Aziz et al., J Carcinogene Mutagene 2014, S10 ll ee ee aa aa nn nn nn nn ee ee rr rr ss ss uu uu ii ii ss ss oo oo DOI: 4172/2157-2518.S10-009 JJ JJ ISSN: 2157-2518 CarCarcinogenesiscinogenesis & Mutagenesis Research Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Mucin Family Genes are Downregulated in Colorectal Cancer Patients Mohammad Azhar Aziz*, Majed AlOtaibi, Abdulkareem AlAbdulrahman, Mohammed AlDrees and Ibrahim AlAbdulkarim Department of Medical Genomics, KIng Abdullah Intl. Med. Res. Ctr., King Saud Bin Abdul Aziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Abstract Mucins are very well known to be associated with different types of cancer. Their role in colorectal cancer has been extensively studied without direct correlation with their change in expression levels. In the present study we employed the human exon array from Affymetrix to provide evidence that mucin family genes are downregulated in colorectal cancer tumor samples. We analyzed 92 samples taken from normal and tumor tissues. All mucin family genes except MUCL1 were downregulated with the fold change value ranging from -3.53 to 1.78 as calculated using AltAnalyze software. Maximum drop in RNA transcripts were observed for MUC2 with a fold change of -3.53. Further, we carried out Integromics analysis to analyze mucin genes using hierarchical clustering. MUC1 and MUC4 were found to be potential biomarkers for human colorectal cancer. Top upstream regulators were identified for mucin genes. Network analyses were carried out to further our understanding about potential mechanisms by which mucins can be involved in causing colorectal cancer. -

Comparative Salivary Proteomics Analysis of Children with and Without Dental Caries Using the Itraq/MRM Approach

Wang et al. J Transl Med (2018) 16:11 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-018-1388-8 Journal of Translational Medicine RESEARCH Open Access Comparative salivary proteomics analysis of children with and without dental caries using the iTRAQ/MRM approach Kun Wang1,2,3, Yufei Wang1,2,3, Xiuqing Wang1,2,3, Qian Ren1,2,3, Sili Han1,2,3, Longjiang Ding1,2,3, Zhongcheng Li1,2,3, Xuedong Zhou1,2,3, Wei Li1,2,3 and Linglin Zhang1,2,3* Abstract Background: Dental caries is a major worldwide oral disease aficting a large proportion of children. As an important host factor of caries susceptibility, saliva plays a signifcant role in the occurrence and development of caries. The aim of the present study was to characterize the healthy and cariogenic salivary proteome and determine the changes in salivary protein expression of children with varying degrees of active caries, also to establish salivary proteome profles with a potential therapeutic use against dental caries. Methods: In this study, unstimulated saliva samples were collected from 30 children (age 10–12 years) with no den- tal caries (NDC, n 10), low dental caries (LDC, n 10), and high dental caries (HDC, n 10). Salivary proteins were extracted, reduced,= alkylated, trypsin digested and= labeled with isobaric tags for relative= and absolute quantitation, and then they were analyzed with GO annotation, biological pathway analysis, hierarchical clustering analysis, and protein–protein interaction analysis. Targeted verifcations were then performed using multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Results: A total of 244 diferentially expressed proteins annotated with GO annotation in biological processes, cellu- lar component and molecular function were identifed in comparisons among children with varying degrees of active caries. -

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared with Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared With Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant Fold Change in term vs second trimester Amniotic Affymetrix Duplicate Fluid Probe ID probes Symbol Entrez Gene Name 1019.9 217059_at D MUC7 mucin 7, secreted 424.5 211735_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 416.2 206835_at STATH statherin 363.4 214387_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 295.5 205982_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 288.7 1553454_at RPTN repetin solute carrier family 34 (sodium 251.3 204124_at SLC34A2 phosphate), member 2 238.9 206786_at HTN3 histatin 3 161.5 220191_at GKN1 gastrokine 1 152.7 223678_s_at D SFTPA2 surfactant protein A2 130.9 207430_s_at D MSMB microseminoprotein, beta- 99.0 214199_at SFTPD surfactant protein D major histocompatibility complex, class II, 96.5 210982_s_at D HLA-DRA DR alpha 96.5 221133_s_at D CLDN18 claudin 18 94.4 238222_at GKN2 gastrokine 2 93.7 1557961_s_at D LOC100127983 uncharacterized LOC100127983 93.1 229584_at LRRK2 leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 HOXD cluster antisense RNA 1 (non- 88.6 242042_s_at D HOXD-AS1 protein coding) 86.0 205569_at LAMP3 lysosomal-associated membrane protein 3 85.4 232698_at BPIFB2 BPI fold containing family B, member 2 84.4 205979_at SCGB2A1 secretoglobin, family 2A, member 1 84.3 230469_at RTKN2 rhotekin 2 82.2 204130_at HSD11B2 hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 2 81.9 222242_s_at KLK5 kallikrein-related peptidase 5 77.0 237281_at AKAP14 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 14 76.7 1553602_at MUCL1 mucin-like 1 76.3 216359_at D MUC7 mucin 7, -

MUC7 Antibody / Mucin 7 (RQ4430)

MUC7 Antibody / Mucin 7 (RQ4430) Catalog No. Formulation Size RQ4430 0.5mg/ml if reconstituted with 0.2ml sterile DI water 100 ug Bulk quote request Availability 1-3 business days Species Reactivity Human Format Antigen affinity purified Clonality Polyclonal (rabbit origin) Isotype Rabbit IgG Purity Antigen affinity purified Buffer Lyophilized from 1X PBS with 2% Trehalose and 0.025% sodium azide UniProt Q8TAX7 Applications Western blot : 0.5-1ug/ml Limitations This MUC7 antibody is available for research use only. Western blot testing of human 1) SW620 and 2) HepG2 lysate with MUC7 antibody at 0.5ug/ml. Predicted molecular weight ~39 kDa. Description Mucin-7 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the MUC7 gene. This gene encodes a small salivary mucin, which is thought to play a role in facilitating the clearance of bacteria in the oral cavity and to aid in mastication, speech, and swallowing. The central domain of this glycoprotein contains tandem repeats, each composed of 23 amino acids. This antimicrobial protein has antibacterial and antifungal activity. The most common allele contains 6 repeats, and some alleles may be associated with susceptibility to asthma. Alternatively spliced transcript variants with different 5' UTR, but encoding the same protein, have been found for this gene. Application Notes Optimal dilution of the MUC7 antibody should be determined by the researcher. Immunogen Amino acids QNKISRFLLYMKNLLNRIIDDMVEQ from the human protein were used as the immunogen for the MUC7 antibody. Storage After reconstitution, the MUC7 antibody can be stored for up to one month at 4oC. For long-term, aliquot and store at -20oC. -

Respiratory Syncytial Virus Activates Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor To

ARTICLE Respiratory syncytial virus activates epidermal growth factor receptor to suppress interferon regulatory factor 1-dependent interferon-lambda and antiviral defense in airway epithelium A Kalinowski1, BT Galen1, IF Ueki2, Y Sun1, A Mulenos1, A Osafo-Addo1, B Clark1, J Joerns1, W Liu1, JA Nadel2, CS Dela Cruz1,3 and JL Koff1 Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) persists as a significant human pathogen that continues to contribute to morbidity and mortality. In children, RSV is the leading cause of lower respiratory tract infections, and in adults RSV causes pneumonia and contributes to exacerbations of chronic lung diseases. RSV induces airway epithelial inflammation by activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a tyrosine kinase receptor. Recently, EGFR inhibition was shown to decrease RSV infection, but the mechanism(s) for this effect are not known. Interferon (IFN) signaling is critical for innate antiviral responses, and recent experiments have implicated IFN-k (lambda), a type III IFN, as the most significant IFN for mucosal antiviral immune responses to RSV infection. However, a role for RSV-induced EGFR activation to suppress airway epithelial antiviral immunity has not been explored. Here, we show that RSV-induced EGFR activation suppresses IFN regulatory factor (IRF) 1-induced IFN-k production and increased viral infection, and we implicate RSV F protein to mediate this effect. EGFR inhibition, during viral infection, augmented IRF1, IFN-k, and decreased RSV titers. These results suggest a mechanism for EGFR inhibition to suppress RSV by activation of endogenous epithelial antiviral defenses, which may be a potential target for novel therapeutics. INTRODUCTION is recommended for the prevention of RSV infection in a small Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a member of the Para- fraction of infants (e.g., born premature, or who have serious myxoviridae family, persists as a significant human pathogen. -

Mucins and Their Role in Shaping the Functions of Mucus Barriers

CB34CH08_Ribbeck ARI 11 September 2018 9:10 Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology Mucins and Their Role in Shaping the Functions of Mucus Barriers C.E. Wagner,1,∗ K.M. Wheeler,2,3,∗ and K. Ribbeck2 1Department of Mechanical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA 2Department of Biological Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA; email: [email protected] 3Microbiology Graduate Program, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018. 34:189–215 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on mucus, mucin, rheology, microbiological interactions, structure, May 11, 2018 permeability The Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology is online at cellbio.annualreviews.org Abstract https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100617- We review what is currently understood about how the structure of the pri- 062818 mary solid component of mucus, the glycoprotein mucin, gives rise to the Copyright c 2018 by Annual Reviews. mechanical and biochemical properties of mucus that are required for it to Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018.34:189-215. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org All rights reserved ∗ perform its diverse physiological roles. Macroscale processes such as lubri- These authors contributed equally to this article cation require mucus of a certain stiffness and spinnability, which are set by Access provided by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on 05/02/19. For personal use only. structural features of the mucin network, including the identity and density of cross-links and the degree of glycosylation. At the microscale, these same features affect the mechanical environment experienced by small particles and play a crucial role in establishing an interaction-based filter. -

Kidney HPV by PCR in Situ Hybridization Using Primers for HPV 6 and 11

264A ANNUAL MEETING ABSTRACTS infection of the recipients and a multidisciplinary laboratory approach to establish an easier visualization of plasma cells). All biopsies were assessed for grade, stage (Ludwig etiological diagnosis. The pathology and IHC staining of transplant-associated LCMV and Batts), and other significant pathologic findings. Type and distribution of infection is most reminiscent of Lassa fever. The contributory role of immunosuppression inflammatory infiltrate with plasma cell count was performed in 26 HIV/HCV patients in the pathology and pathogenesis of LCM in these patients deserves further study. and 17 HCV patients. Results: Comparison of HIV/HCV group vs HCV group: 22/29 vs 36/67 males (75.9% 1220 Howell-Jolly Body-Like Inclusions in the Neutrophils of HIV Positive vs 53.7%); mean age of 45.9 vs 50.7; 51.7% vs 61.2% African Americans, 34.5% vs Patients Are Associated with Low CD4 Counts 19.4% Hispanics and 13.8% vs 19.4% White. Mean HIVRNA load was 17556.2 copies/ µ DL Scurlock, A Wahed. Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA; ml; mean CD4 count was 372.2 cells/ l (ranged from 50-945). HIV/HCV group had University of Texas Health Science Center Houston, Houston, TX. significantly less inflammatory activity (lower grade than HCV group alone, p=0.023), Background: Howell-Jolly body-like inclusions are discrete intracytoplasmic while there was no difference in degree of fibrosis. Due to depletion of lymphocytic inclusions which have been previously observed in the neutrophils of HIV positive infiltrate in the coinfected group, plasma cells were more apparent in HIV/HCV group. -

Pdffiles1/Nij/Grants/236538.Pdf

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Development and Testing of a Rapid Multiplex Assay for the Identification of Biological Stains Author(s): Kevin M. Legg Document No.: 244251 Date Received: December 2013 Award Number: 2011-CD-BX-0205 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Development and Testing of a Rapid Multiplex Assay for the Identification of Biological Stains ______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics University of Denver ______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ______________ By Kevin M. Legg Advisor: Phillip B. Danielson This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. © Copyright by Kevin M. Legg 2013 All Rights Reserved ii This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

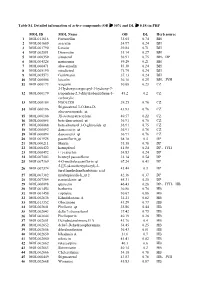

MOL ID MOL Name OB DL Herb Source 1 MOL011616 Fortunellin

Table S1. Detailed information of active compounds (OB ≥ 30% and DL ≥ 0.18) in PHF MOL ID MOL Name OB DL Herb source 1 MOL011616 Fortunellin 35.65 0.74 BH 2 MOL001689 acacetin 34.97 0.24 BH 3 MOL001790 Linarin 39.84 0.71 BH 4 MOL002881 Diosmetin 31.14 0.27 BH 5 MOL000359 sitosterol 36.91 0.75 BH、DP 6 MOL004328 naringenin 59.29 0.21 BH 7 MOL000471 aloe-emodin 83.38 0.24 BH 8 MOL005190 eriodictyol 71.79 0.24 BH 9 MOL005573 Genkwanin 37.13 0.24 BH 10 MOL000006 luteolin 36.16 0.25 BH、JYH 11 MOL000173 wogonin 30.68 0.23 CZ 2-Hydroxyisoxypropyl-3-hydroxy-7- 12 MOL000179 isopentene-2,3-dihydrobenzofuran-5- 45.2 0.2 CZ carboxylic 13 MOL000184 NSC63551 39.25 0.76 CZ Stigmasterol 3-O-beta-D- 14 MOL000186 43.83 0.76 CZ glucopyranoside_qt 15 MOL000188 3β-acetoxyatractylone 40.57 0.22 CZ 16 MOL000085 beta-daucosterol_qt 36.91 0.75 CZ 17 MOL000088 beta-sitosterol 3-O-glucoside_qt 36.91 0.75 CZ 18 MOL000092 daucosterin_qt 36.91 0.76 CZ 19 MOL000094 daucosterol_qt 36.91 0.76 CZ 20 MOL001925 paeoniflorin_qt 68.18 0.4 DP 21 MOL000211 Mairin 55.38 0.78 DP 22 MOL000422 kaempferol 41.88 0.24 DP、JYH 23 MOL000492 (+)-catechin 54.83 0.24 DP 24 MOL007003 benzoyl paeoniflorin 31.14 0.54 DP 25 MOL007369 4-O-methylpaeoniflorin_qt 67.24 0.43 DP 5-[[5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2- 26 MOL007374 43.44 0.3 DP furyl]methylene]barbituric acid 27 MOL007382 mudanpioside-h_qt 2 42.36 0.37 DP 28 MOL007384 paeonidanin_qt 65.31 0.35 DP 29 MOL000098 quercetin 46.43 0.28 DP、JYH、HB 30 MOL001454 berberine 36.86 0.78 HB 31 MOL001458 coptisine 30.67 0.86 HB 32 MOL002636 Kihadalactone A 34.21 -

Engineering Mucus to Study and Influence the Microbiome

REVIEWS Engineering mucus to study and influence the microbiome Caroline Werlang 1, Gerardo Cárcarmo- Oyarce 1,2 and Katharina Ribbeck 1,2* Abstract | Mucus is a 3D hydrogel that houses the majority of the human microbiome. The mucous environment plays an important role in the differentiation and behaviour of microbial phenotypes and enables the creation of spatial distributions. Dysregulation of mucus is further associated with various diseases. Therefore, mucus is the key ingredient to study the behaviour of commensal and pathogenic microbiota in vitro. Indeed, microorganisms cultured in mucus exhibit phenotypes substantially different from those exhibited in standard laboratory media. In this Review, we discuss the impact of mucus on the microbiome and examine the structure and glycosylation of mucins — the main building blocks of mucus. We investigate the impact of glycans on mucin function and highlight different approaches for the engineering of synthetic mucins, including synthesis of the backbone, the design of mucin- mimetic hydrogels and the engineering of glycans. Finally, mucin mimetics for 3D in vitro cell culture and for modulating microbial community structure and function are discussed. Humans have at least as many bacterial cells as human For decades, human tissue culture models were limi- cells1. The human microbiome (BOx 1) has a profound ted to 2D methods that did not facilitate cell differentia- impact on human health, and changes in the compo- tion and spatial separation. Polymers, such as Matrigel, sition of the microbial community are associated with can provide the 3D spatial scaffolding necessary for cell various diseases, ranging from diabetes to depression2,3. differentiation and enable environmental regulation of The development of rapid and efficient DNA sequencing cell fate15. -

Epithelial–Immune Cell Interplay in Primary Sjögren Syndrome Salivary Gland Pathogenesis

REVIEWS Epithelial–immune cell interplay in primary Sjögren syndrome salivary gland pathogenesis Gwenny M. Verstappen1,2, Sarah Pringle 1,2, Hendrika Bootsma1 ✉ and Frans G. M. Kroese1 Abstract | In primary Sjögren syndrome (pSS), the function of the salivary glands is often considerably reduced. Multiple innate immune pathways are likely dysregulated in the salivary gland epithelium in pSS, including the nuclear factor-κB pathway, the inflammasome and interferon signalling. The ductal cells of the salivary gland in pSS are characteristically surrounded by a CD4+ T cell-rich and B cell-rich infiltrate, implying a degree of communication between epithelial cells and immune cells. B cell infiltrates within the ducts can initiate the development of lymphoepithelial lesions, including basal ductal cell hyperplasia. Vice versa, the epithelium provides chronic activation signals to the glandular B cell fraction. This continuous stimulation might ultimately drive the development of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. This Review discusses changes in the cells of the salivary gland epithelium in pSS (including acinar, ductal and progenitor cells), and the proposed interplay of these cells with environmental stimuli and the immune system. Current therapeutic options are insufficient to address both lymphocytic infiltration and salivary gland dysfunction. Successful rescue of salivary gland function in pSS will probably demand a multimodal therapeutic approach and an appreciation of the complicity of the salivary gland epithelium in the development of pSS. Nearly 100 years ago, Henrik Sjögren described a dis striated ducts, consist mostly of CD4+ T cells and B cells, ease whereby patients had a reduced functionality of although other immune cells, including (but not lim the salivary glands (xerostomia) and lacrimal glands ited to) myeloid dendritic cells, plasmacytoid dendritic (xerophthalmia), with accompanying disturbances of the cells (pDCs) and follicular dendritic cells, might also cornea and the conjunctiva (keratoconjunctivitis sicca)1. -

The Bigger Picture: Why Oral Mucosa Heals Better Than Skin

biomolecules Review The Bigger Picture: Why Oral Mucosa Heals Better Than Skin Maaike Waasdorp 1,* , Bastiaan P. Krom 2 , Floris J. Bikker 3 , Paul P. M. van Zuijlen 4,5,6, Frank B. Niessen 5 and Susan Gibbs 1,7 1 Department of Molecular Cell Biology and Immunology, Amsterdam Infection and Immunity Institute, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1108, 1081 HZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected] 2 Department of Preventive Dentistry, Academic Center for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), University of Amsterdam and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 1081 HZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected] 3 Department of Oral Biochemistry, Academic Center for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), University of Amsterdam and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 1081 HZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected] 4 Burn Centre, and Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Hand Surgery, Red Cross Hospital, Vondellaan 13, 1942 LE Beverwijk, The Netherlands; [email protected] 5 Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Hand Surgery, Amsterdam Movement Sciences, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1117, 1007 MB Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected] 6 Department of Pediatric Surgery, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Academic Medical Center, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands 7 Department of Oral Cell Biology, Academic Center for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA), University of Amsterdam and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 1081 HZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Wound healing is an essential process to restore tissue integrity after trauma. Large Citation: Waasdorp, M.; Krom, B.P.; skin wounds such as burns often heal with hypertrophic scarring and contractures, resulting in Bikker, F.J.; van Zuijlen, P.P.M.; disfigurements and reduced joint mobility.