Collaborative Place Name Research in the Community of Kinngait (Nunvavut, Canada)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2019/20 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation | Annual Report 2019/2020 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation | Annual Report 2019/2020

ᕿᑭᖅᑖᓗᒃ ᑯᐊᐳᕆᓴᓐ ᓇᒻᒥᓂᕐᑯᑎᖕᒋᓪᓗ QIKIQTAALUK CORPORATION & Group of Companies Annual Report 2019/20 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation | Annual Report 2019/2020 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation | Annual Report 2019/2020 Chairman’s Message 1 President’s Message 2 Ludy Pudluk 3 About Qikiqtaaluk Corporation 4 Company Profile 4 Qikiqtani Region 5 Company Chart 6 Board of Directors 7 2019-2020 Highlights 8 PanArctic Communications 8 QC Fisheries Research Vessel 9 Inuit Employment and Capacity Building 10 Community Investment and Sponsorships 11 Scholarships 11 QIA Dividend 12 Community Investment Program 12 Event Sponsorship 13 Wholly Owned Subsidiary Activity Reports 15 Fisheries Division Activity Report 15 Qikiqtaaluk Fisheries Corporation 18 Qikiqtani Retail Services Limited 20 Qikiqtaaluk Business Development Corporation 22 Qikiqtaaluk Properties Inc. 24 Nunavut Nukkiksautiit Corporation 26 Qikiqtani Industry Ltd. 28 Aqsarniit Hotel and Conference Centre Inc. 31 Akiuq Corporation 33 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation Group of Companies 34 Other Wholly Owned Subsidiaries 34 Majority Owned Joint Ventures 34 Joint Venture Partnerships 35 Affiliations 36 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation | Annual Report 2019/2020 | Chairman’s Message Welcome to the 2019-2020 Qikiqtaaluk Corporation Annual Report. This past year was a time of focus and dedication to ensuring Qikiqtaaluk Corporation’s (QC) ongoing initiatives were progressed and delivered successfully. In overseeing the Corporation and its eleven wholly owned companies, we worked diligently to ensure every decision is in the best interest of Qikiqtani Inuit and promotes the growth of the Corporation. On behalf of the Board, we would like to share our sadness and express our condolences on the passing of longstanding QC Board member and friend, Ludy Pudluk. Ludy was a Director on QC’s Board for over two decades. -

SIKU: Knowing Our Ice Igor Krupnik · Claudio Aporta · Shari Gearheard · Gita J

SIKU: Knowing Our Ice Igor Krupnik · Claudio Aporta · Shari Gearheard · Gita J. Laidler · Lene Kielsen Holm Editors SIKU: Knowing Our Ice Documenting Inuit Sea Ice Knowledge and Use 123 Editors Dr. Igor Krupnik Dr. Claudio Aporta Smithsonian Institution Carleton University National Museum of Natural Dept. Sociology & History, Dept. Anthropology Anthropology 10th and Constitution Ave. 1125 Colonel By Dr. NW., Ottawa ON K1S 5B6 Washington DC 20013-7012 B349 Loeb Bldg. USA Canada [email protected] [email protected] Dr. Shari Gearheard Dr. Gita J. Laidler University of Colorado, Boulder Carleton University National Snow & Ice Data Dept. Geography & Center Environmental Studies Clyde River NU 1125 Colonel By Drive X0A 0E0 Ottawa ON K1S 5B6 Canada Canada [email protected] [email protected] Lene Kielsen Holm Inuit Circumpolar Council, Greenland Dr. Ingridsvej 1, P. O. Box 204 Nuuk 3900 Greenland [email protected] This book is published as part of the International Polar Year 2007–2008, which is sponsored by the International Council for Science (ICSU) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) ISBN 978-90-481-8586-3 e-ISBN 978-90-481-8587-0 DOI 10.1007/978-90-481-8587-0 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2010920470 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. -

TRPS IKW Q4.Xlsm

Hivumuurutikhaq Ilautquyauyukharnik Havaktitiuyunun Kihidjutikhangit Havaktiuyunun Nunavut Kavamanmi Talvanga: Maatsimi 31, 2021 2020mit‐2021‐mun Talvuuna Kivgaqtuiyunut Kavamatkunni Havagviinni (TRPS) unniudjutit hailiyut qaritauyakkut uvani qaritauyakkurutimi: www.gov.nu.ca ᐅᓇ ᑎᑎᖅᑲᙳᖅᑎᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐊᑐᐃᓐᓇᐅᔪᖅ ᐃᓄᑦᑎᑐᑦ ᑕᐃᒎᓯᖃᖅᖢᓂ: ᐃᓄᖕᓂᒃ ᐱᔨᑦᑎᕐᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᑭᒡᒐᖅᑐᖅᑎᒧᑦ This document is available in English under the title: Towards a Representative Public Service Ce document est disponible en français sous le titre: Vers une fonction publique représentative Talvuuna Kivgaqtuiyunut Kavamatkunni Havagviinni Kihidjutikhangit Havaktiuyunun Nunavut Kavamanmi Talvanga Maatsimi 31, 2021 Iipu 2021 Iqaluit, Nunavut ISBN 978‐1‐55325‐482‐9 ©Nunavut Kavamangat, 2020 Iluanitut Titiraqhimayut Ilitugidjutikhaq 2 Havaktiit Naitumik Titiraqhimayut Nunavut Kavamanmi Havaktun 3 Havagiangit Naitumik Titiraqhimayut Nunalaani 4 Havaktiit Naitumik Titiraqhimayut Havagviitigun Nunalingni Kavamatkunnilu Pivikhaqautikkut 5 Pitquhiliqiyikkut 6 Pivalliayuliqiyikkut Ingilrayuliqiyitkullu 7 Ilinniaqtuliqiyikkut 8 Avataliqiyikkut 9 Kavamaliqiyikkut 10 Qatanngutiliqiyikkut 11 Kiinauyaliqiyikkut 12 Munarhiliqiyikkut 13 Havaktuliqiyikkut 14 Maligaliqiyikkut 15 Afisiani Maligaliuryuarvingmi 16 Nunavut Ilihaliarpaarvikmi 17 Nunavut Nanmniqaqtun Atukiutiliqiyut Kuapulasini 18 Nunavut Igluliqiyiryuakkut 19 Qulliq Alruyaqtuqtunik Ikumadjutiit 20 Havaktiit Naitumik Titiraqhimayut Katitiqhimayut Nunavut Kavamatkunni Havagviit 21 Ihivriungniq Nunavunmi Inuit Havaktitukharnik 22 Sivuliqtiksat Ayuiqhauyukhat -

March 10, 2021

NUNAVUT HANSARD UNEDITED TRANSCRIPT WEDNESDAY, MARCH 10, 2021 IQALUIT, NUNAVUT Hansard is not a verbatim transcript of the debates of the House. It is a transcript in extenso. In the case of repetition or for a number of other reasons, such as more specific identification, it is acceptable to make changes so that anyone reading Hansard will get the meaning of what was said. Those who edit Hansard have an obligation to make a sentence more readable since there is a difference between the spoken and the written word. Debates, September 20, 1983, p. 27299. Beauchesne’s 6th edition, citation 55 Corrections: PLEASE RETURN ANY CORRECTIONS TO THE CLERK OR DEPUTY CLERK Legislative Assembly of Nunavut Speaker Hon. Paul Quassa (Aggu) Hon. David Akeeagok Joelie Kaernerk David Qamaniq (Quttiktuq) (Amittuq) (Tununiq) Deputy Premier; Minister of Economic Development and Transportation; Minister Pauloosie Keyootak Emiliano Qirngnuq of Human Resources (Uqqummiut) (Netsilik) Tony Akoak Hon. Lorne Kusugak Allan Rumbolt (Gjoa Haven) (Rankin Inlet South) (Hudson Bay) Deputy Chair, Committee of the Whole Minister of Health; Minister Deputy Speaker and Chair of the responsible for Seniors; Minister Committee of the Whole Pat Angnakak responsible for Suicide Prevention (Iqaluit-Niaqunnguu) Hon. Joe Savikataaq Deputy Chair, Committee of the Whole Adam Lightstone (Arviat South) (Iqaluit-Manirajak) Premier; Minister of Executive and Hon. Jeannie Ehaloak Intergovernmental Affairs; Minister of (Cambridge Bay) John Main Energy; Minister of Environment; Minister of Community and Government (Arviat North-Whale Cove) Minister responsible for Immigration; Services; Minister responsible for the Qulliq Minister responsible for Indigenous Hon. Margaret Nakashuk Energy Corporation Affairs; Minister responsible for the (Pangnirtung) Minister of Culture and Heritage; Utility Rates Review Council Hon. -

English French Inuktitut Inuinnaqtun

Property Tax Arrears List ᓇᖕᒥᓂᖁᑎᒋᔭᐅᔪᒥᒃ ᑖᒃᓰᔭᖅᑕᐅᓂᖅ ᐊᑭᓕᒃᓴᑐᖃᒃᑯᑦ ᑎᑎᕋᖅᓯᒪᔪᑦ Liste des arriérés d'impôt foncier Piqutini Taaksiinni Atugaqaqnikkut Titiraqhimayut June 30, 2021 / ᔫᓂ 30, 2021-ᒥᑦ / 30 juin, 2021 Properties outside Iqaluit owing more than $5,000. Propriétés situées à l’extérieur d’Iqaluit devant plus de 5 000 $. ᐃᖃᓄᐃᑦ ᓯᓚᑖᓂᒃ ᓇᖕᒥᓂᕆᔭᐅᔪᑦ ᐊᑭᓕᓴᖃᖅᑐᓄᑦ $5,000. Piqutilrit hilataani Iqalungni atugaqqaqtut avatquhimayumik $5,000. The GN is publishing this list as required by Section 97 of the Property Assessment and Taxation Act. To view the full arrears list, visit www.gov.nu.ca/finance. To pay your Le GN publie cette liste conformément aux exigences de l’article 97 de la Loi sur taxes, or if you have questions or concerns, please contact the Department of Finance l’évaluation et l’impôt fonciers. Pour consulter la liste complète des arriérés, visitez le at 1-800-316-3324 or [email protected]. site www.gov.nu.ca/finance. Pour payer vos impôts fonciers ou si vous avez des questions ou des préoccupations, veuillez contacter le ministère des Finances au ᐃᓚᖓ 97 ᓄᓇᕗᑦ ᒐᕙᒪᖓᓂᒃ ᑎᑎᕋᖅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᓇᖕᒥᓂᖃᖅᑎᓄᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᓂᖅ numéro 1 800 316-3324, ou à l’adresse [email protected]. ᑖᒃᓯᐃᔭᕐᕕᐊᓄᑦ ᐱᖁᔭᓂᒃ. ᑎᑎᕋᖅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐊᑭᓕᒃᓴᑐᖃᓕᒫᑦ, ᑕᑯᒋᐊᕈᓐᓇᖅᐳᑎ GN nuitipkaliqtaa una titiraq pitquyauhimaningani uumani Ilangani 97 uvani Property www.gov.nu.ca/finance-ᒧᑦ. ᐊᑭᓕᕋᓱᒡᓗᒋᑦ ᑖᒃᓯᑎᑦ, ᐊᐱᖅᑯᑎᖃᕈᕕᓪᓘᓐᓃᑦ Assessment and Taxation Act. Takulugu tamaat atugaqqanikkut titiraqhimayuq, ᐃᓱᒫᓗᑎᖃᕈᕕᓘᓐᓃᑦ, ᑮᓇᐅᔭᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᓐᓄᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᓇᓱᒍᓐᓇᖅᐳᑎᑦ 1-800-316-3324-ᒧᑦ takuyaqtuqlugu www.gov.nu.ca/finance. Akiliriami taaksitit, apiqquutikhaqaruvulluunniit ᐅᕝᕙᓘᓐᓃᑦ [email protected]ᒧᑦ. ihumaaluutinikluunniit, uqaqatigitjavat Kiinauyaliqiyitkut uvani 1-800-316-3324 unaluun- niit [email protected]. -

Connections to the Land: the Politics of Health and Wellbeing in Arviat, Nunavut Is About Traditional Knowledge As Process

Connections to the Land: The Politics of Health and Wellbeing in Arviat Nunavut by Sherrie Lee Blakney A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Natural Resources Institute University of Manitoba December 2009 Copyright © 2009 by Sherrie Blakney THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ***** COPYRIGHT PERMISSION Connections to the Land: The Politics of Health and Wellbeing in Arviat Nunavut by Sherrie Lee Blakney A Thesis/Practicum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of the University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © 2009 Permission has been granted to the Library of the University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Library of Canada to microfilm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and to University Microfilms Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright owner. Abstract Connections to the Land: the Politics of Health and Wellbeing in Arviat, Nunavut is about traditional knowledge as process. The thesis examines the relationships between Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) [“the Inuit way of doing things”; traditional knowledge (TK);], Inuit perceptions of health and wellbeing and the land; and what the relationships mean for integrated coastal and ocean management. -

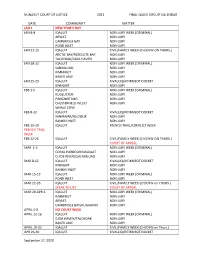

FINAL 2021 Quick Circuit Schedule.Pdf

NUNAVUT COURT OF JUSTICE 2021 FINAL QUICK CIRCUIT CALENDAR DATE COMMUNITY MATTER JAN 1 NEW YEAR’S DAY JAN 4-8 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) ARVIAT NON-JURY CAMBRIDGE BAY NON-JURY POND INLET NON-JURY JAN 11-15 IQALUIT CIVIL/FAMILY WEEK (CH/CHW ON THURS.) ARCTIC BAY/RESOLUTE BAY NON-JURY TALOYOAK/GJOA HAVEN NON-JURY JAN 18-22 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) SANIKILUAQ NON-JURY KIMMIRUT NON-JURY BAKER LAKE NON-JURY JAN 25-29 IQALUIT KIVALLIQ/KITIKMEOT DOCKET KINNGAIT NON-JURY FEB 1-5 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) KUGLUKTUK NON-JURY PANGNIRTUNG NON-JURY CHESTERFIELD INLET/ NON-JURY WHALE COVE FEB 8-12 IQALUIT KIVALLIQ/KITIKMEOT DOCKET SANIRAJAK/IGLOOLIK NON-JURY RANKIN INLET NON-JURY FEB 15-19 IQALUIT FRENCH TRIAL/CONFLICT WEEK FRENCH TRIAL WEEK FEB 22-26 IQALUIT CIVIL/FAMILY WEEK (CH/CHW ON THURS.) COURT OF APPEAL MAR 1-5 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) CORAL HARBOUR/NAUJAAT NON-JURY CLYDE RIVER/QIKITARJUAQ NON-JURY MAR 8-12 IQALUIT KIVALLIQ/KITIKMEOT DOCKET KINNGAIT NON-JURY RANKIN INLET NON-JURY MAR 15-19 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) POND INLET NON-JURY MAR 22-26 IQALUIT CIVIL/FAMILY WEEK (CH/CHW on THURS.) SPEAK TO LIST COURT OF APPEAL MAR 29-APR 2 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) KIMMIRUT NON-JURY ARVIAT NON-JURY CAMBRIDGE BAY/KUGAARUK NON-JURY APRIL 5-9 NO COURT WEEK APRIL 12-16 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) GJOA HAVEN/TALOYOAK NON-JURY BAKER LAKE NON-JURY APRIL 19-23 IQALUIT CIVIL/FAMILY WEEK (CH/CHW on Thurs.) APR 26-30 IQALUIT KIVALLIQ/KITIKMEOT DOCKET September 17, 2020 NUNAVUT COURT OF JUSTICE 2021 FINAL QUICK CIRCUIT CALENDAR DATE COMMUNITY MATTER MAY 3-7 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) PANGNIRTUNG NON-JURY RANKIN INLET NON-JURY MAY 10-14 IQALUIT CIVIL/FAMILY WEEK (CH/CHW on Thurs.) COURT OF APPEAL KUGLUKTUK NON-JURY SANIKILUAQ NON-JURY MAY 17-21 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) FRENCH TRIAL KINNGAIT NON-JURY WEEK MAY 24-28 IQALUIT KIVALLIQ/KITIKMEOT DOCKET MAY 24 – VICTORIA DAY MAY 31-JUNE 4 IQALUIT NON-JURY WEEK (CRIMINAL) WHALE COVE/CHESTERFIELD IN. -

CIRNAC Comments to NIRB Re: Notice of Screening for Qikiqtaaluk Corporation’S “Qikiqtaaluk Inshore Fisheries Research” Project Proposal Nunavut Regional Office P.O

CIRNAC Comments to NIRB Re: Notice of Screening for Qikiqtaaluk Corporation’s “Qikiqtaaluk Inshore Fisheries Research” Project Proposal Nunavut Regional Office P.O. Box 100 Iqaluit, NU, X0A 0H0 Your file - Votre référence 20YN019 Our file - Notre référence GCdocs# 95897476 July 2, 2021 Mia Otokiak Junior Technical Advisor I Nunavut Impact Review Board P.O. Box 1360 Cambridge Bay, NU, X0B 0C0 via NIRB public registry Re: Notice of Screening and Comment request for Qikiqtaaluk Corporation’s “Qikiqtaaluk Inshore Fisheries Research” Project Proposal Dear Mia Otokiak, On June 10, 2021 the Nunavut Impact Review Board (NIRB) invited parties to comment on Qikiqtaaluk Corporation’s “Qikiqtaaluk Inshore Fisheries Research” project proposal. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) appreciates the opportunity to provide comments and offers the responses below as it pertains to the NIRB’s request: Whether the Project is of a type where the potential adverse effects are highly predictable and mitigable with known technology, (please provide any recommended mitigation measures); CIRNAC #1: Waste Management and Nunavut Communities The Proponent indicates that both combustible and domestic wastes from the vessel are to be disposed of in approved facilities in the study communities. It is unclear if the Proponent will be using no-contact methods when disposing of wastes to prevent potential transmission of COVID-19 to the communities. CIRNAC recommends that the Proponent ensure that any combustible wastes are removed and disposed of using the same no contact approach proposed for restocking in the study communities, and that proper disposal is arranged with the study community members prior to arriving in the study community(ies). -

Psar 2019-2020 - Final En.Pdf

Cover page photos (left to right): Nunavut Arctic College staff take a stand against bullying. Community and Government Services staff gather in the boardroom. Jennifer Ullulaq shows her mother-in-law’s necklace that is at the Winnipeg Art Gallery Human Resources Deputy Minister Sheila Kolola joins Hivuliqtikhanut Leadership Development Program’s Senior Managers’ Series graduates Finance staff before the budget lockup Departments of Culture & Heritage and Economic Development & Transportation and Winnipeg Art Gallery staff get a tour of the Qaumajuq (formerly Inuit art centre) while under construction in Winnipeg Culture and Heritage’s Ida Ayalik-McWilliam and Elizabeth Alakkariallak-Roberts at the department’s trade show booth during the Kitikmeot Trade Show Nunavut Housing Corporation employees enjoy their cultural immersion day Table of Contents Message from the Minister ........................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Establishment of the Department of Human Resources .............................................................................. 6 Delivering Services in Unprecedented Times ........................................................................................... 6 Public Service at a Glance ............................................................................................................................ -

Blic Servic I Re Ort Cover Page Photos (Left to Right): Nunavut Arctic College Staff Take a Stand Against Bullying

bJn_JJ ...oc..>c. J\;:><;b<C..c-<lnc..c_5>C Building Nunavut Together Nunavuliuqatigiingniq Batir le Nunavut ensemble blic Servic I Re ort Cover page photos (left to right): Nunavut Arctic College staff take a stand against bullying. Community and Government Services staff gather in the boardroom. Jennifer Ullulaq shows her mother-in-law’s necklace that is at the Winnipeg Art Gallery Human Resources Deputy Minister Sheila Kolola joins Hivuliqtikhanut Leadership Development Program’s Senior Managers’ Series graduates Finance staff before the budget lockup Departments of Culture & Heritage and Economic Development & Transportation and Winnipeg Art Gallery staff get a tour of the Qaumajuq (formerly Inuit art centre) while under construction in Winnipeg Culture and Heritage’s Ida Ayalik-McWilliam and Elizabeth Alakkariallak-Roberts at the department’s trade show booth during the Kitikmeot Trade Show Nunavut Housing Corporation employees enjoy their cultural immersion day Table of Contents Message from the Minister ........................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Establishment of the Department of Human Resources .............................................................................. 6 Delivering Services in Unprecedented Times .......................................................................................... -

COVID-19 GN Update

COVID-19 GN Update As part of the Government of Nunavut’s (GN) effort to protect Nunavummiut against the risk of COVID-19, GN Departments are implementing the following: Department of Health Services For all the latest information and resources about COVID-19 in Nunavut, go to: https://www.gov.nu.ca/health/information/covid-19-novel-coronavirus For the latest information on current public health restrictions, go to: https://www.gov.nu.ca/health/information/nunavuts-path For information on upcoming vaccine clinics go to: https://gov.nu.ca/health/information/covid-19-vaccination COVID-19 case status: June 7 Total Total Total Total Deaths Total Current tests Confirmed active recovered persons persons cases cases cases followed followed 16,467 649 1 644 4 8656 437 *Confirmed cases include those meeting the national case definitions. Persons followed includes individuals with specific symptoms and exposures as well as others who are self-monitoring or self-isolated. Not all of these individuals have symptoms or require testing. *There may be a delay reporting attribution and statistics from cases acquired in Southern Canada. 12 cases that were detected out of territory have been attributed to Nunavut. This includes 3 deaths. Not all NU residents with COVID-19 detected out of territory will be attributed to Nunavut. For the latest COVID-19 information and GN Departments updates in all languages: https://www.gov.nu.ca/health/information/covid-19-novel-coronavirus; https://www.gov.nu.ca INUK | ENG | IKW | FRE INUK | ENG | IKW | FRE COVID-19 community -

Procurement Activity Report 2016/17

GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT Procurement Activity Repor t kNo1i Z?m4fiP9lre pWap5ryeCd6 t b4fy 5 Nunalingni Kavamatkunnilu Pivikhaqautikkut Department of Community and Government Services Ministère des Services communautaires et gouvernementaux Fiscal Year 2016/17 GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT Procurement Activity Report Table of Contents Purpose . 3 Objective . 3 Introduction . 3 Report Overview . 4 Sole Source Contract Observations . 5 General Observations . 9 Summary . 11 1. All Contracts (> $5,000) . 11 2. Contracting Types . 15 3. Contracting Methods . 18 4. Sole Source Contract Distribution . 22 Appendices Appendix A: Glossary and Definition of Terms . 27 Appendix B: Sole Source (> $5,000) . 29 Appendix C: Contract Detailed Listing (> $5,000) . 31 1 GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT Procurement Activity Report Purpose The Department of Community and Government Services (CGS) is pleased to present this report on the Government of Nunavut (GN's) procurement and contracting activities for the 2016/17 fiscal year. Objective CGS is committed to ensuring fair value and ethical practices in meeting its responsibilities. This is accomplished through effective policies and procedures aimed at: • Obtaining the best value for Nunavummiut overall; • Creating a fair and open environment for vendors; • Maintaining current and accurate information; and • Ensuring effective approaches to meet the GN's requirements. Introduction The Procurement Activity Report presents statistical information and contract detail about GN contracts as reported by GN departments to CGS's Procurement, Logistics and Contract Support section. Contracts entered into by the GN Crown agencies and the Legislative Assembly are not reported to CGS and are not included in this report. Contract information provided in this report reflects contracts awarded and reported during the 2016/2017 fiscal year.