Britannia Rule the Waves – the Royal Navy Past and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Naval Aviation Museum Are Tangible Examples of Your Continuing Interest and Support

The Quarterly Journal of the Fleet Air Arm Association of Australia Volume 7 Number 2 April 1996 Published by the Fleet Air Ann Association of Australia Inc. - Print Post Approved - PP201494/00022 Editor: John Arnold-PO Box 662, NOWRA NSW 2541, Australia - Phone (044) 232014 - Fax (044) 232412 Slipstream - April 1996 - Page 2 FOREWORD by Rear Admiral Murray B Forrest AM RAN Assistant Chief of Naval Staff (Personnel) Although I have never really been closely associated with the Fleet Air Arm, I do remember a rather daunting day or two at sea in MELBOURNE as a Cadet and several great Gunroom and Wardroom parties; looking through back numbers of your very spirited and entertaining magazine also reminds me of some wonderful people of my youth; and I do have many friends among your number . But that said, we are all a part of the same very fine Service and as Navy's current 'people' person, I am delighted to come to the party. Professionally, my early dealings with Naval Aviation were confined to the not so glamorous world of logistics where I was amazed by the staggering quantities of bits and pieces demanded by Air Engineers to keep those airframes flying and also gained an understanding of their commitment to air worthiness. The ROE [role of effort] has not diminished! Now, I have to man the aircraft and provide the technicians; not always an easy task but, as ever, there are many fine people in the Naval Personnel Division and the wider community to assist. In that role, the excellent contribution of the Fleet Air Arm Association in maintaining the esprit de corp is invaluable. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Assessing the British Carrier Debate and the Role of Maritime Strategy Bosbotinis, James Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 Assessing the British Carrier Debate and the Role of Maritime Strategy James Bosbotinis PhD in Defence Studies 2014 1 Abstract This thesis explores the connection between seapower, maritime strategy and national policy, and assesses the utility of a potential Maritime Strategy for Britain. -

Knights Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath

WESTMINSTER ABBEY ORDER OF SERVICE AND CEREMONY OF THE OATH AND INSTALLATION OF KNIGHTS GRAND CROSS OF THE MOST HONOURABLE ORDER OF THE BATH IN THE LADY CHAPEL OF KING HENRY VII THE CHAPEL OF THE ORDER IN THE ORDER’S 293 rd YEAR 11.15 am THURS DAY 24 th MAY 2018 THE INSTALLATION CEREMONY Although the Order of the Bath as we Even this fell into abeyance after know it today was created by Letters 1812, because of the enlargement of Patent passed under the Great Seal on the Order in 1815, and the installation 18 th May 1725, the origins of the ceremony was formally abolished in ceremony, which takes place in the 1847. It was revived in 1913 in the Henry VII Chapel, can be traced back modified form which continues in use to the 14 th century. A pamphlet of that to the present. Today the Knights are time refers to Knights receiving ‘a installed as a group and do not Degree of Knighthood by the Bath’ actually occupy their own stalls and describes part of the knighting during the installation. ceremony thus: The offering of gold and silver ‘The Knight shall be led into the represents partly a surrendering of Chapel with melody and there he worldly treasure and partly a shall un-girt him and shall offer his recognition by the new Knight of his sword to God and Holy Church to be duty to provide for the maintenance laid upon the Altar by the Bishop’. of Christ’s Church on earth. In today’s ceremony, the gold is represented by The original installation ceremony two sovereigns: 1895 with the head of was based largely on that used at the Queen Victoria and 1967 with the Coronation of Henry V on 9 th April head of Queen Elizabeth II. -

Makes for Luke

Royal Australian' T he official newspaper of the Royal Australian Navy Navy News. Locked Bag 12. Pyrmonl 2009 Aegistere<l by Australia Post Publication VOLUME 40, No. 11 Phone: (02) 9563 1202FIDC:(02) 9563 1411 June 16, 1997 AdvenisingPtlone:(02) 95631539 Fax (02)95631 411 No. VBH8876 Visit makes a grin• for Luke H~~~rt~ : d of H ~~0X'; NEWCASTLE when she visited her hom e por t of Ne"'castle after an 18 month absence. First of the visitors were 40 young people from the Hunter Orthopaed ic School, a do pted by the ship 's complement as its fal'ourUe charity. Aged from 10 to 16 years and wit h many confi ned to. wheelchairs, t he children's visit provid ed a busy time for LEUT Karen Rockmann and ABET Carolyn Denford and their helpers. NEW CASTLE wit h her The student's inspection of the ship got underway in the a fternoon , wilh a cockta il party on the helideck. Saturday and Sunday saw public inspection of the ship with NEWCASTLE putting to sea on Monday, June 2, for d rill in the eastern area training zone. "' we h ad not been to Newcastle for 18 months," SHLT Belinda Wood , the ship's liaison of1i ce r, said. " It was ver y s uccessful visil 10 our ' home' pori," she Old enemies• mourn • boffin LEUT Rob Gr.lOt In peace from NSCHQ 31 Pyrmont .... 3) only A torpedo all aek .... as H~~~1 f(lrt';~/I ' :; goe~ s mg. bUI u"s e1ther I~;~:: ah:~:e b~Ct~~ni~ launched on the USS Cou~lf, 1'lIIain, meon· a bug lh:1I stops the ing of th e depot ship CHI CAGO but failed 10 /~ur. -

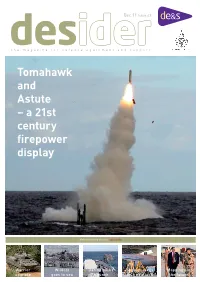

Tomahawk and Astute – a 21St Century Firepower Display

Dec 11 Issue 43 desthe magazine for defenceider equipment and support Tomahawk and Astute – a 21st century firepower display Virtual warfare in focus See inside Warrior Wildcat Daring packs Support takes Mapping out upgrade goes to sea a punch on a new look the future FEATURES 6 24 Warfare staff go to war The Royal Navy has unveiled its new Maritime Composite Training System to a fanfare of trumpets and applause, marking the most radical change to its training for more than 40 years. 26 It’s the Army’s PlayStation generation Members of the British Army's PlayStation generation head to Helmand Province on the latest Operation Herrick deployment having honed their soldiering skills in virtual combat 28 Kestrel reaches full flight Project Kestrel – Information Systems and Services' reliable backbone communications network – is now complete, guaranteeing increased capacity and improved quality of communications in Afghanistan 2011 30 Defence Secretary praises ‘dedicated people’ New Defence Secretary Philip Hammond has praised 'the cover image most dedicated people in the public service' as he outlined A Tomahawk land attack missile is pictured being his vision for defence in his first public speech since fired byHMS Astute during her latest set of trials. The succeeding Dr Liam Fox missile, one of two fired on the trial, demonstrated complex evasive manoeuvres during flight and hit its designated target on a missile range DECEMBER desider NEWS Assistant Head, Public Relations: Ralph Dunn - 9352 30257 or 0117 9130257 5 Warrior in £1 billion -

Castletownbere Lifeboat Crew

• If Autumn 2004 For everyone who helps save lives at sea SAPcodf . INfOOl 569 ' Jf A royal gopening for t College All h.inks If iid your money to so The trouble is they won't tell you who they're lending it to, so you may be shocked to find out what your savings end up funding. Triodos Bank is different. We only work with organisations that benefit people and the environment, like organic food production, Pair Trade companies and charities. We're the only commercial bank in the UK to publish an annual list of the organisations we lend to, which tells savers exactly how their money is working. You give to yet your savings animal charities, fund intensive People are at the heart of everything we do. farming. As a customer you'll speak to real people who understand and share your values. Also, you'll be pan of an increasingly powerful community of savers who not only receive a healthy financial interest rate, but a strong social return on their savings. To open a Triodos Bank savings account, call free on 0500 008 720 or visit w www.triodos.co.uk/savings for more information. Triodos® Bank Make your money make a difference Autumn 2004 lifeboat A royal tening for it College In this issue Lifeboats Feature: A day to remember HM The Queen opens The Lifeboat College The magazine of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution Feature: The Survival Centre Registered Charity Number 209603 The RNLI's centre of excellence for sea survival training The official opening Page 2 Issue 569 Lifeboat Lottery 9 Chairman: Sir Jock Slater CCB ivo rx Chief Executive: -

Strategic Defence Review

Strategic Defence Review Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Defence by Command of Her Majesty July 1998 White Paper Factsheets Essays Key Points Background MODERN FORCES FOR THE MODERN WORLD CONTENTS ● Introduction by the Secretary of State for Defence ● Chapter 1 A Strategic Approach to Defence ● Chapter 2 Security Priorities in a Changing World ● Chapter 3 Defence Missions and Tasks ● Chapter 4 Deterrence and Disarmament ● Chapter 5 The Future Shape of our Forces ● Chapter 6 A Policy for People ● Chapter 7 Equipping the Forces ● Chapter 8 Smart Procurement ● Chapter 9 Defence Support for the 21st Century ● Chapter 10 Resources ● Chapter 11 Conclusion: Modern Forces for the Modern World ● Appendix Strategic Defence Review - Supporting Essays White Paper Factsheets Essays Key Points Background Order A Copy INTRODUCTION BY THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE THE Rt. Hon. GEORGE ROBERTSON MP 1. The British people are rightly proud of their Armed Forces. They want, indeed expect, the Government to provide strong defence. The Strategic Defence Review does just that. By modernising and reshaping our Armed Forces to meet the challenges of the 21st century, this Review will give our Services the firm foundation they need to plan for the long term. 2. The Review is radical, reflecting a changing world, in which the confrontation of the Cold War has been replaced by a complex mixture of uncertainty and instability. These problems pose a real threat to our security, whether in the Balkans, the Middle East or in some troublespot yet to ignite. If we are to discharge our international responsibilities in such areas, we must retain the power to act. -

Mary Rose Trust 2019 Annual Report

Mary Rose Trust Annual Review 2019 MARYROSEANNUALREPORT MR Final after Chair.indd 1 30/09/2019 16:08 2 MARYROSEANNUALREPORT MR Final after Chair.indd 2 30/09/2019 16:08 Over my forty-year involvement, I have been delighted to see the Trust evolve from an ambitious and determined group of enthusiasts undertaking the world’s biggest ever underwater archaeological excavation into a world class museum and professional organisation, respected around the world for its work. I am particularly pleased with the way the Trust continues to develop the fascinating Mary Rose story, with the latest scientific research revealing more compelling stories about the origins of the Mary Rose’s ship’s company, showing Tudor England was most likely far more diverse than we thought. It all makes for a spellbinding story and one that visitors continue to find as compelling as we all did when we were diving on, and excavating, the ship all those decades ago. I remain immensely proud of having played a small part in recovering the immense treasures of the Mary Rose for the nation and send my heartfelt thanks to all those, past and present, who support the Trust and help make sure that future generations can be inspired by this truly remarkable story. 3 MARYROSEANNUALREPORT MR Final after Chair.indd 3 30/09/2019 16:08 Highlight of our trip to Portsmouth. Seeing the salvaged ship and artefacts from 500 years ago, preserved so well. It’s spine tingling. TripAdvisor SK - Nuneaton 4 MARYROSEANNUALREPORT MR Final after Chair.indd 4 30/09/2019 16:08 Foreword was the first year of trading as an independent ‘Best Business enue’ and ‘Best Access and Inclusivity’. -

Knights Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath

3 WESTMINSTER ABBEY ORDER OF SERVICE AND CEREMONY OF THE INSTALLATION OF KNIGHTS GRAND CROSS OF THE MOST HONOURABLE ORDER OF THE BATH IN THE LADY CHAPEL OF KING HENRY VII THE CHAPEL OF THE ORDER IN THE ORDER’S 289TH ANNIVERSARY YEAR 11.15 am FRIDAY 9TH MAY 2014 - 1 - THE INSTALLATION CEREMONY Although the Order of the Bath as we know It was revived in 1913 in the modified form it today was created by Letters Patent passed which continues in use to the present. under the Great Seal on 18 May 1725, the Today the Knights are installed as a group origins of the ceremony which takes place in and do not actually occupy their own Stalls the Henry VII Chapel can be traced back to during the installation. the 14th Century. A pamphlet of that time refers to Knights receiving ‘a Degree of The offering of gold and silver represents Knighthood by the Bath’ and describes part partly a surrendering of worldly treasure and of the knighting ceremony thus: partly a recognition by the new Knight of ‘The Knight shall be led into the Chapel his duty to provide for the maintenance of with melody and there he shall un-girt him Christ’s Church on earth. In today’s and shall offer his sword to God and Holy ceremony, the gold is represented by two Church to be laid upon the Altar by the sovereigns: 1876 with the young head of Bishop’. Queen Victoria and 1899 with the veiled head of Queen Victoria. The silver is The original installation ceremony was represented by two silver crowns, 1819 with based largely on that used at the Coronation the laureate head of King George III and of Henry V on 9th April 1413. -

Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR)

5 December 2000 Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) GEN Of The Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, US A 2 Apr 51 – 30 May 52 GEN Matthew B. Ridgway, US A 30 May 52 – 11 Jul 53 GEN Alfred M. Gruenther, US A 11 Jul 53 – 20 Nov 56 GEN Lauris Norstad, US AF 20 Nov 56 – 1 Jan 63 GEN Lyman L. Lemnitzer, US A 1 Jan 63 – 1 Jul 69 GEN Andrew J. Goodpaster, US A 1 Jul 69 – 15 Dec 74 GEN Alexander M. Haig, Jr. US A 15 Dec 74 – 29 Jun 79 GEN Bernard W. Rogers, US A 29 Jun 79 - 26 Jun 87 GEN John R. Galvin, US A 26 Jun 87 - 24 Jun 92 GEN John M. Shalikashvili, US A 24 Jun 92 - 22 Oct 93 GEN George A. Joulwan, US A 22 Oct 93 - 11 Jul 97 GEN Wesley K. Clark, US A 11 Jul 97 - 3 May 00 GEN Joseph W. Ralston, US AF 3 May 00 - present Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe (DSACEUR) Field Marshal The Viscount Montgomery 2 Apr 51 - 23 Sep 58 of Alamein, UK A GEN Sir Richard Gale, UK A 23 Sep 58 - 22 Sep 60 GEN Sir Hugh Stockwell, UK A 22 Sep 60 - 1 Jan 64 Marshal of The Royal Air Force 1 Jan 64 - 1 Mar 67 Sir Thomas G. Pike, UK AF GEN Sir Robert Bray, UK A 1 Mar 67 - 1 Dec 70 GEN Sir Desmond Fitzpatrick, UK A 1 Dec 70 - 12 Nov 73 GEN Sir John Mogg, UK A 12 Nov 73 - 15 Mar 76 GEN Sir Harry Tuzo, UK A 15 Mar 76 - 2 Nov 78 (2 DSACEURs from Jan 78 – Jun 93) LT GEN Gerd Schmueckle, GE A 3 Jan 78 - 1 Apr 80 GEN Sir Jack Harman, UK A 2 Nov 78 - 9 Apr 81 ADM Gunther Luther, GE N 1 Apr 80 - 1 Apr 82 ACM Sir Peter Terry, UK AF 9 Apr 81 - 16 Jul 84 GEN G. -

Public Bodies 2003 PUBLIC BODIES 2003 © CROWN COPYRIGHT 2003

Public Bodies 2003 PUBLIC BODIES 2003 © CROWN COPYRIGHT 2003 Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to Her Majesty's Stationery Office, Licensing Division, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ First published 2003 ISBN 0 7115 0435 0 ii CONTENTS Commentary iv Statistical Tables vii Public Bodies 2003 by Sponsor Departments UK Government Cabinet Office 1 Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster 4 Department for Culture, Media and Sport 5 Ministry of Defence 19 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister 24 Department for Education and Skills 28 Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 32 Export Credits Guarantee Department 44 Food Standards Agency 45 Foreign and Commonwealth Office 48 Department of Health 51 Home Office 66 Inland Revenue 72 Department for International Development 73 Lord Chancellor’s Department 74 Northern Ireland Court Service 79 Northern Ireland Office 81 Oftel 84 OFWAT 86 Royal Mint 87 Scotland Office 88 Department of Trade and Industry 89 Department for Transport 102 HM Treasury 106 Department for Work and Pensions 107 Devolved Administrations Northern Ireland Executive 111 Review of Scottish Public Bodies 135 Review of Welsh Public Bodies 137 Task Forces, Ad hoc Advisory Groups and Reviews 2003 138 Task Forces, Ad hoc Advisory Groups and Reviews 2003 by Sponsor Departments 140 Index to Public Bodies and Task Forces, Ad hoc Advisory Groups and Reviews 206 iii Commentary COMMENTARY Public Bodies 2003 is the latest in a series of annual publications providing information on public bodies sponsored by the UK Government. This edition gives a snapshot as at 31 March 2003. -

Knights Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath

WESTMINSTER ABBEY ORDER OF SERVICE AND CEREMONY OF THE INSTALLATION OF KNIGHTS GRAND CROSS OF THE MOST HONOURABLE ORDER OF THE BATH IN THE LADY CHAPEL OF KING HENRY VII THE CHAPEL OF THE ORDER IN THE ORDER’S 285th ANNIVERSARY YEAR 11.15 a.m. TUESDAY 25 MAY 2010 THE INSTALLATION CEREMONY ALTHOUGH the Order of the Bath as we know it installation ceremony was formally abolished in today was created by Letters Patent passed under 1847. It was revived in 1913 in the modified form the Great Seal on 18 May 1725, the origins of the which continues in use to the present. Today the ceremony which takes place in the Henry VII Knights are installed as a group and do not Chapel can be traced back to the 14 th Century. A actually occupy their own Stalls during the pamphlet of that time refers to Knights receiving installation. ‘a Degree of Knighthood by the Bath’ and describes part of the knighting ceremony thus: The offering of gold and silver represents partly ‘The Knight shall be led into the Chapel with a surrendering of worldly treasure and partly a melody and there he shall un-girt him and shall recognition by the new Knight of his duty to offer his sword to God and Holy Church to be provide for the maintenance of Christ’s Church laid upon the Altar by the Bishop ’. on earth. The gold is represented by two sovereigns: 1872 , London minted; the other in The original installation ceremony was based 1879 , Sydney minted. The silver is represented by largely on that used in 1413 at the Coronation of silver proof Twenty Five Pence, 1980, Queen Henry V.